In an interview with Tytus Szabelski, who was awarded the special prize in last year’s edition of the Esteemed Graduates of Polish Academies of Fine Arts contest, we discuss the role of an artist, the relevance of distinction between a copy and an original, the means of expression, and the twists and turns which led him to the creation of “All that is melted…”.

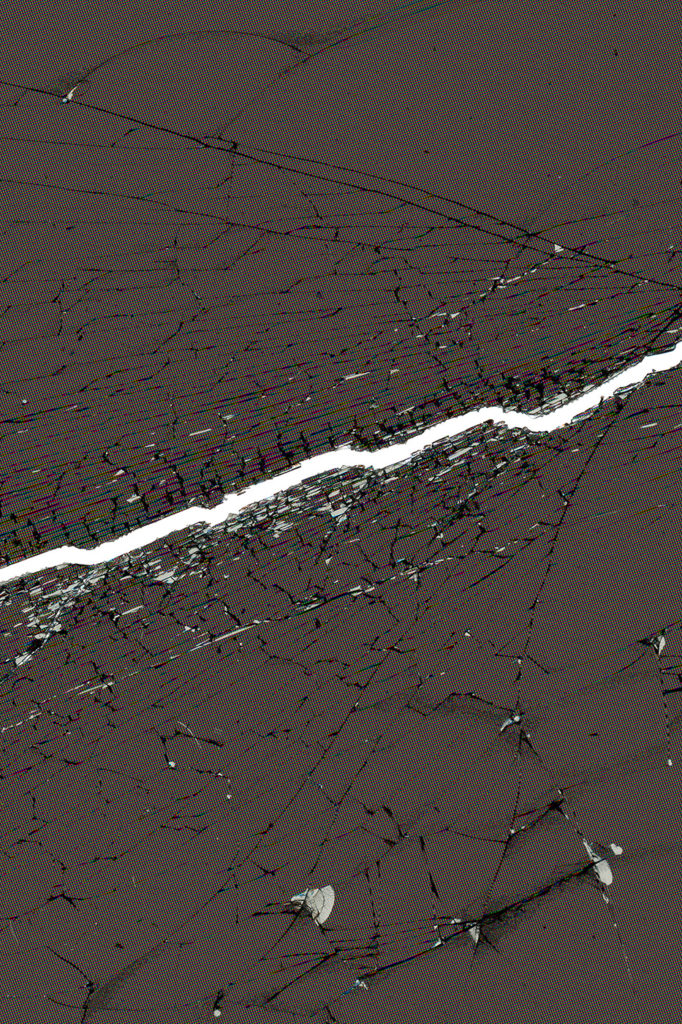

Tytus Szabelski, Untitled, from the series “All that is Melted…”

Ania Dziuba: What stimulated your interest in the subject of “All that is melted…”? Where did it all begin? And where does the title come from?

Tytus Szabelski: The project’s title derives from the name of Marshall Berman’s book “All That is Solid Melts Into The Air”, which is actually a quote from Marx’s Communist Manifesto. I am not sure I can pinpoint the precise moment or thing that triggered my interest. For a while, I’ve found the general reception of the latest technology rather fascinating. So much of the content we produce is stored digitally in the cloud. We are not familiar with the way in which the tools we use function, and our experience is limited to its physical manifestation – the form the tools are enclosed in or the screen which the text and images are projected onto. Even now we are both enjoying the benefits of new technology completely oblivious to the mechanics of it. So, I reversed the quote; all that is solid hasn’t melted, but disappeared into thin air. Initially, I intended to explore the subject of the elusiveness of technology, the tangible machines in charge of our intangible spheres of life, but then I changed my mind. I decided I wanted to focus more on the image generated in the virtual reality. It took me two semesters in my final year of studies to complete the project although its scope is far from impressive: just two minimalistic art installations and four photographs. I don’t like working in a hurry or on a deadline, time to think is crucial for ideas to surface. While the work is still in progress, various inspirations and associations collide with each other. We don’t live in a vacuum, after all. Every image we see, every piece of writing we read leaves a mark that may influence the shape of our work at some point in the future.

AD: Exactly. What was your initial concept and how does it now relate to the end result?

TS: The project underwent a series of modifications and it obviously turned out to be completely different from what I’d imaged at first, namely the kind of typology illustrating the flipside of virtual reality inspired by server rooms and such. Perhaps I wanted to follow in Lewis Baltz’s footsteps. The photographs featured in the exhibit New Topographics (1975) were my point of departure, my inspiration if you wish, even though it might not be very evident. The idea evolved into the visualization of radio waves transmitted by a Wifi router. I was going to register those waves, take photographs where I collected the data and subsequently use it to intervene with the pictures’ source code. Suddenly, my attention turned towards the image itself due to some technical difficulties, unsatisfactory results, as well as the discussions I had with the supervisors of my graduate art project – prof. Krzysztof Baranowski and prof. Piotr Chojnacki from the University of Arts in Poznań. I have a tendency to take detours from the path I’ve chosen. I rarely follow the plan and create something according to plan. I often reevaluate my decisions. However, many people claim that the consistency of my artworks suggests otherwise.

AD: The radical transformation you mentioned took me by surprise, too. I suspected only slight alterations. Anyway, you seem fascinated with the duality, or rather the subversion, of reality. Illusion and unreality play a crucial role in your project “Forms of the Impossible”.

TS: Absolutely, I believe both people and their surrounding reality are full of contradictions. People think one thing and do the opposite. The world we live in is both real and unreal. The only solution is to come to terms with it instead of looking for a panacea or explanation. To some extent, “Forms of the Impossible” embody our abandonment of the utopian ideals of achieving a sense of harmony detached from reality and thus rejected by a society that wasn’t offered anything else, a goal or a reference point, in return. At that time, I was wondering whether one might continue to pursue some goal in spite of their clear awareness of how impossible it is for them to actually achieve it. I don’t know, but I hope so. Both art projects feature some elements of illusion because it baffles the viewers who then puzzle over the image they see. Illusion encourages viewers to seek answers to the questions they’ve posed to themselves.

AD: Let’s go back to “All that is melted…” for a minute. Many people living in the twenty-first century refuse to admit the dual nature of reality, or in other words, its division into the virtual and real world. What was the audience’s response to your project? Was your idea in any way challenged or criticized?

TS: No, not really. Some viewers took issue with the form itself since they perceived it as too hermetic and final, which was in fact the point. The series was designed to convey a certain message you can, but don’t have to, agree with. No one expressed strong disapproval, which was a shame, really. I would’ve loved to engage in a passionate polemic. I find it incredibly important.

AD: What sort of means of expression or mediums do you feel the most comfortable with?

TS: Photography, definitely. I’ve been taking a variety of photographs for a while now. My need to transgress its boundaries is demonstrated in “All that is melted…”, as well as “Forms of the Impossible”, where photographs are incorporated into art installations. That’s a subject I’d certainly like to explore further, not only as an artist, but also as a doctoral student at the University of Arts, from a purely theoretical standpoint. Combining photography and installation seems extremely compelling on the grounds that it epitomizes the correlation between the virtual and the real, between the image and matter or space. One can’t exist without the other even though they’re opposites.

AD: Now we’ll just have to wait and see where this new path will lead you as an artist. Why does new media art dominate the contemporary art scene? Does digital technology offer new opportunities for an artist or does is it just pandering to the viewer?

TS: Both, in fact. Young artists want to tap into the inexhaustible potential of the advanced tools and devices available while making their work supposedly more palatable to the audience due to the employed technology’s ubiquity. At times, the trend gives rise to such odd hybrids as post-internet painting. There are numerous advocates of film photography who still use the wet collodion or daguerreotype. Those techniques’ sense of nostalgia permeates the photographs, which can never fully deviate from their aesthetics. Therefore, in my art I avoid film photography. I only take pictures in an old-fashioned way for my own personal use. What’s the point in choosing an expensive technique that limits my options? Needless to say, some true aficionados fetishize analog photography and embrace those limitations, especially when it comes to the number of photographs you can take. Personally, I prefer taking abundant photographs, which I can always delete, if it means that one of them turns out perfect. The road to success is long and winding.

Tytus Szabelski, Untitled, from the series “All that is Melted…”

AD: Don’t you think that it is virtual reality that nowadays feels more real?

TS: No, I don’t think it does. The complex connection between virtual and actual reality can be traced back to the 1990s, the era in which personal computers became affordable and widespread, the Internet was invented and the VR headsets, which enabled a stereoscopic projection of a parallel reality onto the screen, missed the mark for many reasons. Currently, more advanced technology has contributed to the current revival of interest in VR systems such as Oculus Rift. Back then, “Matrix” was the product of fears that offered an augmented and slightly brutal interpretation of Jean Baudrillard’s theory. Still, the idea of total immersion in virtual reality, which would replace the real world completely, seems far-fetched to me. Claiming that one reality will replace another runs the risk of making a gross oversimplification and misunderstanding complex matter. That’s what my project is all about. You look at the photographs and can’t define what it is that you are seeing. One of my art installations draws the viewer right into the virtual loop by reflecting their live-recorded image on the screen. Yet, this viewer, their very body, is still grounded in reality since they actually stand in the art gallery.

AD: Does VR provide a distortion or an extension of reality? Or is it something else entirely?

TS: Neither. It arises from the need to enhance the reality, make it more “real”, which may sometimes seem skewed. I consider myself a champion of augmented rather than virtual reality. New technology meets very basic human needs without generating new ones. On the other hand, it poses some ethical dilemmas, for instance the influence of artificial intelligence or bots on our everyday reality. Those problems can be solved provided that we change our attitudes.

AD: What is your opinion on the original vs. copy debate, taking into account how easy it is to disseminate and replicate someone’s work?

TS: That’s a difficult question. I believe it all depends upon the area we apply those notions to. In law, the clear definition of a copy and original associated with the authorization of some documents or a person’s signature is of paramount importance as opposed to any expression of creativity in e.g. music, art, Facebook posts or memes. In this case, the notions of copy and original lost their meaning long before the rise of the Internet and a brand-new understanding of the adjective ‘virtual’. Without a shadow of doubt, I have never had a truly ingenious thought in my lifetime. Every single day, every single one of us experiences the wealth of stimuli that determine what we think about, and how. The Internet merely represents and boosts the process since it enables a free and uninterrupted flow of information. By the same token, originality may be simply defined as one’s ability to absorb and shape the outside influence in some unprecedented manner.

AD: Has originality been somehow curbed by people’s overwhelming dissemination of images and pieces of information? Do we endlessly rehash old ideas? Does the fact that our generation was denied the possibility of an original thought and action appear as a natural order of things, the byproduct of years of civilization’s growth? Do we belong to the generation of parasites and imitators?

TS: I’d say it was inevitable rather than natural development. The invention of the wheel was probably already inspired by someone noticing that round objects roll faster, which isn’t necessarily a bad thing. I refuse to succumb to nostalgia and mindless glorification of the past. It’s a dead end. However, one still has to be aware of the profound influence the past exerts on the present and be capable of forming new configurations of ‘old’ ideas. Look at the modernists and their purported originality. Look at le Corbusier and his fascination with the geometry of classical Greek architecture. Modernists embraced former and surrounding attitudes, remolded them and finally integrated into their philosophy, which wasn’t nearly as revolutionary as they thought it was.

AD: Indeed, nostalgia reached its pinnacle in the nineteenth century. I believe we’ve already learned how to use the greatest achievements of the past to good advantage.

TS: Maybe. But in popular culture nostalgia is still alive and kicking.

AD: Thank you for speaking to us, Tytus.

Tytus Szabelski, Untitled (passage), from the series Forms of the Impossible

Tytus Szabelski, Untitled (library), from the series “Forms of the Impossible”

[author] [author_image timthumb=’on’]http://contemporarylynx.co.uk//wp-content/uploads/2017/02/tytus_szabelski.jpg[/author_image] [author_info]Tytus Szabelski (born 1991) is a graduate of the Nicolaus Copernicus University in Toruń, Poland, where he majored in journalism and social studies, as well as the University of Arts (UAP) in Poznań, where he studied photography. Currently, he attends the Interdisciplinary Doctoral Studies at UAP. His photographs have been featured in local and national press. He has collaborated with the Center of Contemporary Art in Toruń, Miłość Gallery in Toruń and Krytyka Polityczna magazine (Political Critique). One of the members of the Toruń-based art collective “Grupa nad Wisłą” (the Vistula Group). His works have been displayed on a number of solo and group shows. He was awarded the Cultural Scholarship of the City of Toruń in 2012 and 2016, and selected as one of the finalists of the national and international contests for outstanding graduation works: the Esteemed Graduates of the Polish Academies of Fine Arts in Gdańsk, Poland and StartPoint Prize in Prague, Czech Republic (2016). His artistic practice focuses on landmark photography, which usually captures the post-war modern architecture. He is an editor of Magneta – the online magazine dedicated to contemporary photography (www.magentamag.com); as well as a contributor to the online edition of SZUM magazine, the Polish quarterly about contemporary art.[/author_info] [/author]