Ewa Axelrad is a multimedia artist, author of photographs and installations the starting point for which often is the space of the gallery.

Ewa Axelrad, Warm Leatherette

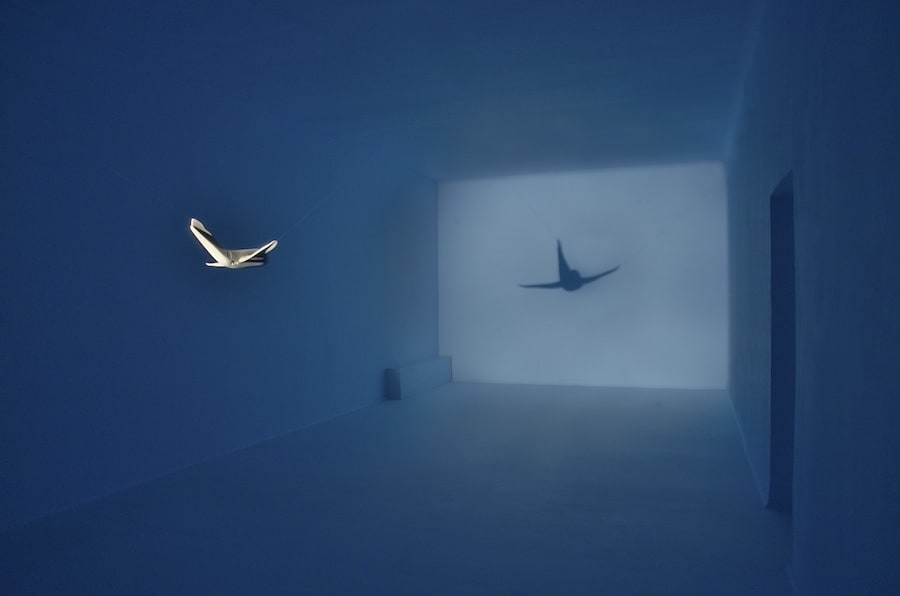

At Rest, 2012, silicone (27cm x 7cm x 7cm)

installation view at Czytelnia Sztuki and at BWA Warszawa. Courtesy of Artist and BWA Warszawa gallery.

S.K: Your solo exhibition in BWA Warszawa entitled Warm Leatherette finished very recently. In the exhibition we could see, among others, colour photographs of crashed metal, a deformed passenger’s seat, a misshapen crash barrier from a motorway shoulder.

The exhibition brought me, personally, associations with Andy Warhol’s Death and Disasters series from 1960s. He was collecting cut outs/photographs from tabloids showing tragic accidents. Then he would enlarge and multiply them. He would change the colours into warm reds and delicate pinks. He was transforming the macabre into a pleasant aesthetic experience.

E.A: Warhol’s series is an interesting point of reference, perhaps contextualising my work through Death and Disasters could make us reflect on the changes, which took place in culture throughout the last 50 years. Of course, contemporary art history bears many references to accidents, especially car accidents. I think Warhol’s series is particularly interesting in a sense that it was being created in the bloom of the culture of consumption and during the period of people’s biggest fascination with it. Today we are precisely at the other end in this relation. His whole series is based not on a single image, but on a repetition, which refers hugely to the representation of death in media and to the pop desensitisation caused by the multitude of those representations. I think today it wouldn’t be too potent to refer to the same phenomena in culture. I think that the subject of the multitude of images, although still quite there, got saturated over decades and hence lots its impact.

S.K: What are your works intending to make us aware of? Are you interested in the experience of a catastrophe? Is your work a reflection of the current economic crisis? Is the exhibition a certain kind of a modern memento mori? A documentary on the modern world? What is the message behind the Vt/Warm Leatherette project?

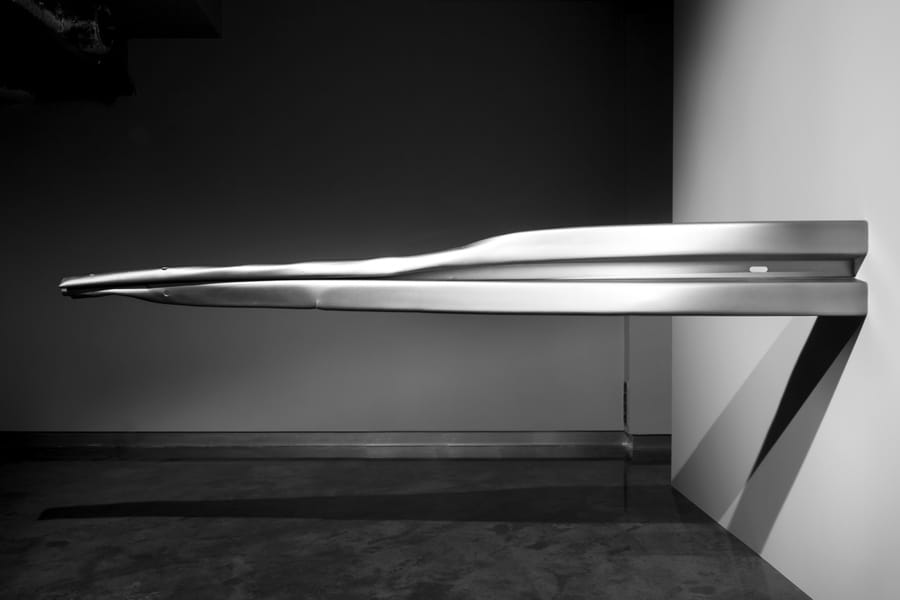

Ewa Axelrad, Warm Leatherette The Absorbent, 2012, installation, installation view at Czytelnia Sztuki in Gliwice

steal, silver car body paint (total size 3m x 3m x 3m, the barrier 308cm x 40cm x 40cm). Courtesy of Artist and BWA Warszawa gallery.

E.A: WL focuses on the fetishistic potency and a sculptural dimension of speed and a crash, through which it addresses the sense of confusion between the solid and the precarious present in our relationship with technology and its aesthetics. My project grew on a totally different (if referring to Warhol) background and it’s defined by my relationship with the so-called ‘tragic’ (this word usually refers to some sort of ‘accidental’) death. But for me touching upon the subject of a ‘tragic‘ death is mostly questioning the relationship with the stability of life and our own physicality, and this question lies somewhere at the core of this project.

I find this relationship a powerful subject especially when the terrorist attacks on civilians are so commonly heard about, as a consequence of which the right to feel safe is taken away from you. Let’s take Boston a few weeks back: one second the marathon, the cult of the fitness of the body, the next second its contradiction: the dismembered bodies of the random spectators. Have you noticed what a nation-wide joy, cheer and a sense of ‘victory’ spread throughout Boston after the younger of the bombers was captured? This is a perfect portrayal of a society catching the ‘beast’, as if one man was to personify all the danger that has been threatening America. The reason I mention the acts of terrorism is because of this context of randomness, which is intrinsic to them; this randomness is also intrinsic to accidents: car accidents, railway catastrophes, etc. The randomness of accidents undermines our sense of control over our existence (when the culture of consumption is based on giving us a sense of control in a form of products). What I’m trying to say is that from my point of view – and I believe from the point of view of my generation – the omnipresence of death inhabited our consciousness differently than e.g. my parents’ in Poland (who grew up in the overbearing presence of the cold war); you find out about an act of terrorism committed on another continent as quickly as you do about a cyclist hit by a truck on the neighbouring street (news all too familiar in London).

I’ve been massively interested in the sense of vigilance and readiness for a long time now, which permeates most of my projects proceeding Warm Leatherette. I say ‘proceeding’ because this is probably my first project in which this vigilance made way to some kind of pleasure, which is very much a new situation for me. Here, I stopped exploring this vigilance, and in its place I started to, in a formal sense,’play’ with these ‘post-accident remains’. Reflecting on this after a period of time, I think that in this exhaustion from being exposed to so many dramatic images, there is a moment in which in order to keep on looking, you need to see something different, and if you don’t see it, you actively start to ‘subvert’ it and introduce seeming lightness. Similarly, if you don’t want the viewer to avert their eyes, you must constantly lead them on, seduce anew.

For me this moment of ‘subversion’ was looking at the train derailment in Szczekociny. I remember staring at the thumbnails in google images, when it suddenly hit me how soft the crashed carriages seemed, as if empty aluminium tins folded very softly. And this impulse led me to look for post-accident car bodies, but specifically those, which were similarly softly ‘crumpled’ instead of being dramatically ripped apart, burnt or scratched. This way I intend to somewhat change viewer’s focal point: from afar the photographs look very soft and abstract, as you approach the image it becomes more defined, you notice small scratches, cracks; Your perception of them changes.

Ewa Axelrad, Warm Leatherette, The Absorbent, 2012, installation, installation view at Czytelnia Sztuki in Gliwice steal, silver car body paint (total size 3m x 3m x 3m, the barrier 308cm x 40cm x 40cm). Courtesy of Artist and BWA Warszawa gallery.

S.K: The book Warm Leatherette which sums up the exhibition in Gliwice has just come out (published by Czytelnia Sztuki, Gliwice Museum (available on Czytelnia Sztuki). Apart from the visual summary of the project (in cooperation with Maga Sokalska) the publication includes texts by Tomek Plata and Huw Hallam. Plata in Catastronauts (see here) refers to the English writer J.G. Ballard, who tackles the subject of fascination with a car crash. While the text of Huw Hallam untitled: crash refers to the theme of the economic crisis. Can you tell us more about the publication?

E.A: Both texts by Tomek Plata and Huw Hallam are free literary responses to the project. They were invited to respond to the visual material from the exhibition Vk in Czytelnia Sztuki. There is a lot of Ballard in Tomek’s text, which I guess comes from his interest in the writer and from a few chats that we had about my initial ideas for the project. In Catastronauts Tomek takes a look at Ballard in the Polish context and poses the question why wasn’t Ballard read in Poland more widely.

As far as I’m concerned, Ballard’s Crash served me more as an ignition spark. It was also under his influence that the song Warm Leatherette was written by Daniel Miller, from which I borrowed the title for my car seat piece and after which eventually the whole project was named (at the beginning it was presented as Vk, a Polish symbol for Vt – terminal velocity). So Ballard accompanied me at the beginning of my work on this project, but equally did Virilio. There are certainly references to Ballard’s Crash in parts of my project but I certainly wouldn’t define it through his lens. At some point I tried to consciously remove myself from fiction and chose to refer to things with which I can directly relate to, things that bug and haunt me in some way. Nevertheless, this show has been strongly contextualised by Ballard, I guess mostly because of the erotic depiction of a car crash, which can be very appealing. What interested me in this erotic side of a car crash was a few aspects, such as the empowering aesthetics of a vehicle but also a threshold state; both sex and death can be considered as such moments and a part of the exhibition touches upon these borderline, terminal states. I was once asked about the anatomy of an accident and I think there is something in this ‘anatomical’ approach. Science allows us to see so many cross-sections, things that happen inside of something that we wouldn’t normally see, whether it’s a cross-section of a sexual act in which we can see genital penetration or a simulation of tectonic movements where we can see how particular layers of the ground push against each other. We have no access to ‘see’ these things in action and similarly with a so-called ‘tragic accident’.

In the second text, Huw Hallam in a particularly interesting way extracts the subject of the economic crisis, which, I must say, was first a bit of a surprise to me. Indeed, in my project everything is suspended as if in a void, it is on the borderline of a surface glamour and at the same time impotence, as in case of the soft silicone wings of an aircraft (At Rest). Usually proud and firm wings, often symbolising the potency of technology, patriotism, etc. here become soft and slack. I think that this impotency more or less affects all of us at present, after all we are at a point when we started doubting our values, whether you mean the reliability on technology, improvement of a human body or capitalism. Huw’s text juxtaposes these phenomena with the mechanisms of economy in a very unique way, plus it is exceptionally well written (I recommend reading it in original).

Ewa Axelrad, PLANT

Site-specific installation, mixed-media. An accretion of the gallery ceiling.

Arsenal Gallery, Poznan 2011, Courtesy of Artist.

S.K: In your numerous contextual spatial projects you have demonstrated that you treat space wholly. You treat the interior of the gallery like a painter treats his canvas. You arrange individual objects in space. They start to correspond with each other visually. On top of this you tend to use light to change the viewer’s perception, as in project ‘Oranż’.

How do you start working on your projects? What does this creative process look like?

E.A: Indeed, the space of the gallery is incredibly important to me, although depending on it can be a limitation as some works, especially site-specific ones, often require disproportionately intense preparation time as compared to the time of their existence, and it can be difficult to recreate them in a different spatial situation. I ascribe much significance to it because the character of the space also determines the perception of even a small work of art. That doesn’t mean that I always work with the actual matter of a gallery space, although I often do so when an opportunity arises, but I always try to use its characteristics to the maximum. Many of my projects only start to take shape once I know in what type of space they can be shown. I like total experiences. Because the actual pathway to the reception of a piece of art starts very early, not just when you see it closely, it starts at least when you open the gallery door, when you experience the change of temperature, the weight of the door as you open them, the intensity of the light in the hallway, the texture of the floor, the lady selling the tickets, etc. That is why I often stop at the idea stage and let the project wait for the right space and time.

When it comes to the subjects of my works, they often derive from matters, which have a strong impact on me, which I experience everyday, like those I mentioned before. A subject gets stuck in my head, often for unclear reasons so I explore it through research, I pick up on motifs in the media and this way things start to form some more complete image, and when that happens, I know I am onto something, and that gives me a reason to pursue the project. When I work I usually don’t know exactly how everything relates to each other, so for me the creative process is about finding an answer, sometimes these answers come a lot later, after the work is finished, for example in a conversation like this one. If I knew all the answers to all the questions from the start, I would find the whole process very tiresome, especially as it’s then devoid of this gut feeling that you have to do it, because you already know what the answer will be.

Ewa Axelrad, ORANƵ (eng. ORANGE) Site-specific installation 2011, mixed media, Biala Gallery, Lublin Fair Child UC-123K 3d print of a mutated aircraft model, azure paint, spot-light, dimensions variable. Courtesy of Artist

Ewa Axelrad, ORANƵ (eng. ORANGE) Site-speific installation 2011, mixed media, Biala Gallery, Lublin Leakage (Based on Two Photographs of Disturbing Resemblence) Duratrans, lightbox 136x98x70cm.

S.K: You’ve studied both in Poland and in London at the Academy of Fine Art in Poznań at the department of multimedia communication and the department of photography at the Royal College of Art. In London. Today you are a visiting lecturer at the Camberwell College of Art at the University of Arts London. How would you compare art education in those two countries? Is there something in particular that strikes you as a student or as a lecturer at the English university?

E.A: The position of the student is totally different in these two cases. In Poznań I had a feeling that each student has many program choices to make, in a way the students shape themselves, and it’s up to them how much work they do or don’t, what they read, who they spend their time with, which studios they attend, etc. One graduates from such a school feeling quite ‘grown up’. There is a sense of certain freedom but it also means that nothing will come easily, you won’t be spoon-fed. And the reality is harsh. Most people at the university will not have a chance to work with art once they graduate, whether it’s because of the economic situation or for other reasons. In Poland it’s extremely difficult to make a living and make art at the same time, not to mention renting a studio and lead a decent life. In order to survive you have to stay incredibly determined for a long period of time, and there still is the great uncertainty. But also for those reasons you’ve got people who take their work very seriously, if they make this decision to make art, they do it for good, you don’t get people who are only half-commited.

Whereas colleges such as the RCA tend to be more protective of their students. The groups tend to be more like classes, they check attendance, you get photocopies of the texts you should read, you are given a schedule and a list of more or less compulsory reading. On one hand it’s nice because you do feel like you belong to something larger, like someone is overseeing your development but on the other hand you may feel more like a ‘pupil’ in a class. At the same time the university is a great platform on which you learn about the outside realities, there is far more contact with the outside world and this is musn’t be understated. I think Polish universities, such as Poznań Academy of Fine Arts impact on a high level of Polish art, probably also due to the harshness of their reality. At the same time this potential hardly gets supported after graduation, which differs greatly from English reality. I think that after learning this independence and self-reliance in Poland, I was able to draw more out of the RCA. Because, like at UAL, there is a lot to draw upon. Having said that, I admit that as the RCA student I didn’t have the easiest time, since (used to the multi-disciplinary freedom of the Poznań Academy of Fine Arts) I was more interested in spending time at the sculpture or other departments rather than at my own, and this didn’t necessarily fit into the rather rigid structure of my department.

S.K: What advice regarding choices and creative work would you give to young artists, who are starting their careers?

E.A: Get a real job. 😉

Thank you.

Translated by Ewa Tomankiewicz

- More info: Ewa Axelrad website: http://ewa-axelrad.com/

- BWA Warszawa gallery: www.bwawarszawa.pl