Our day-to-day tasks at the magazine involve looking at works of artists, reading interviews, reviews, monographies and academic publications. I admit it with some unease, but what becomes most prominent in the deluge of information is the attitude of looking up to the West – Paris, London, New York, which is so common among people from Central Europe. It is true that seeing artists from this region being incorporated into the international discussion and reflection on modern/contemporary art is particularly satisfying, because it is about the artist or an important work of art speaking and being able to speak to everyone, not only a narrow group. However, this also falsifies the image a little. We look far, but we often do not pay appropriate attention to what is happening here and now. And it often happens that important things or beginnings of artistic movements, changes, and dialogues start just outside our doorstep! They take place on the outskirts of the “metropolis”. Beyond the centre, which seems to be a black hole consuming everything, or at least enough to make everything outside them meaningless. And it is beyond the centre where ideas are born. It is where the exchange of views happens without buffoonery or pressure of the glamour of the WORLDY scene.

Very well, but what does that mean?

We will be trying to return to the perspective in which the periphery becomes the new artistic centre, and thus the centre of our interests.

But where to start?

Let’s start from what is the closest.

End of May, beginning of June, the first summer days – the eyes of the artistic scene in Europe (and beyond) are turned to Architecture Biennale in Venice and Manifesta in Petersburg. So, we decided to look in a completely different direction.

The Czech Republic.

The destination is not an obvious one at a first glance. The first thing that comes to mind when thinking about the Czech Republic is its wonderful art deco, pre-war cubism and surrealism. It was a place where modernist art thrived both in architecture and visual arts. Its ideas were realised and changed the face of its society, it organised it and ruled over it, the best example of which is the great enterprise of Tomasz Bata in Zlin. Also the later decades of 1960 and 1970 are great examples of neo-constructivism, the search for structure and composition, challenging op-art and kinetic art. And nowadays? It is probably a great simplification and specialists on Central European art would frown at such a statement, but my personal choice would be David Černý;)

But coming back to the point…

Olomouc 2014, photo Contemporary Lynx

Far from the main centres of art, 252 km east of the capital, lays Olomouc. The Renaissance and Baroque character of the town does not suggest what lies beneath. The small Museum of Modern Art in Olomouc hides a wonderful art collection. The narration of the exhibitions leads the viewer through 20th century Central-European art. However, there is no division into individual countries. Instead, more interestingly, what has been highlighted is the unity of thought and ideas, which fascinated the artists beyond political and geographic divisions. Works of Jan Wojnar, beside those by Ryszard Winiarski and Lubomír Příbil have been displayed. An object by David Černý is displayed next to a painting by Jerzy “Jurry” Zieliński.

Tadeusz Kantor, Postać martwa, 1950, oli on canvas, photo Contemporary Lynx

Upon entering, the visitors are welcomed by the nestor of Polish avant-garde art – Tadeusz Kantor. He is more known in the world for his theatre and his informel paintings, but here we get to see a beautiful painting from his early period – Dead Figure dated 1950, in which you can trace his fascination with surrealism and cubism. Back then these inspirations stimulated more than one artist (although one has to admit that thanks to his travels he introduced them to the Warsaw and Cracow society and among the members of the later created Cracow Group). This is best exemplified by the work of Kazimierz Mikulski which is displayed beside the painting of Alfred Lenica combing the artist’s interest in surrealism, tachisme and informel. The museum also has in its collection early compositions on paper by Jonasz Stern, which not in the least foreshadow his future searchings, slightly cubistic geometrical compositions, as well as Pomocnik. a painting by Tadeusz Brzozowski dated 1959.

Alfred Lenica, Olomouc 2014, photo Contemporary Lynx

Alfred Lenica, Coulou Poisoning – Stains in the Sky and on the Earth, 1956, oil on canvas, 99 x 95 cm, Olomouc 2014, photo Contemporary Lynx

Kaziemierz Mikulski, Untitled, 1948, oil, indian ink on cardboard, 30 x 21 cm, Olomouc 2014, photo Contemporary Lynx

The collection’s jewel is the room with, to resort to simplification, representations of op-art, kinetic and conceptual art, an interesting example of which is the formally poetic Polish Relief 81.12.13 (for V.W.) created by György Jovánovics.

György Jovánovics, Polish Relief, 81.12.13 (for V.W.), plaster, 138 x 108 x 6 cm, Olomouc 2014, photo Contemporary Lynx

Not far from the creations of Miroslav Šnajdr, Vladislav Mirvald, or Hugo Demartini is a work by Ryszard Winiarski. Obszar 132. Like the remaining works of this artist it is comprised of black and white fields, the composition of which depends on the random toss of a dice. They are the result of a game of chance and mathematic calculus of probability. Although it is not displayed, the collection also includes Composition by Henryk Stażewski, who also subjected his work to strong geometric rigour.

However, the Olomouc Art Collection does not only comprise of avant-garde, conceptual or neo-constructive artists. In the adjacent room we have Jerzy „Jurry” Zieliński, or the representative of the artistic group from 1990s called Gruppa Włodzimierz Pawlak, who derives his ideas from Zieliński’s thought. His work attacked social norms and political and religious conventions. By employing slogans and simple symbols, he treated them with ridicule or condescending, while revealing their shallowness, fleeting character and incompliance with the modern world.

David Černý, Olomouc 2014, photo Contemporary Lynx

Jerzy „Jurry” Zieliński, Untitled, 1975, oil on canvas, 90 x 100 cm, Olomouc 2014, photo Contemporary Lynx

Włodzimierz Pawlak, Olomouc 2014, photo Contemporary Lynx

This cursory, slightly tongue-in-cheek approach to the past and heritage is wonderfully presented by another artist – Kama Sokolnicka – invited last year to the Prostor Zlin exhibition to Zlin – a very important centre of thought from the point of view of the modernist heritage of Czechoslovakia.

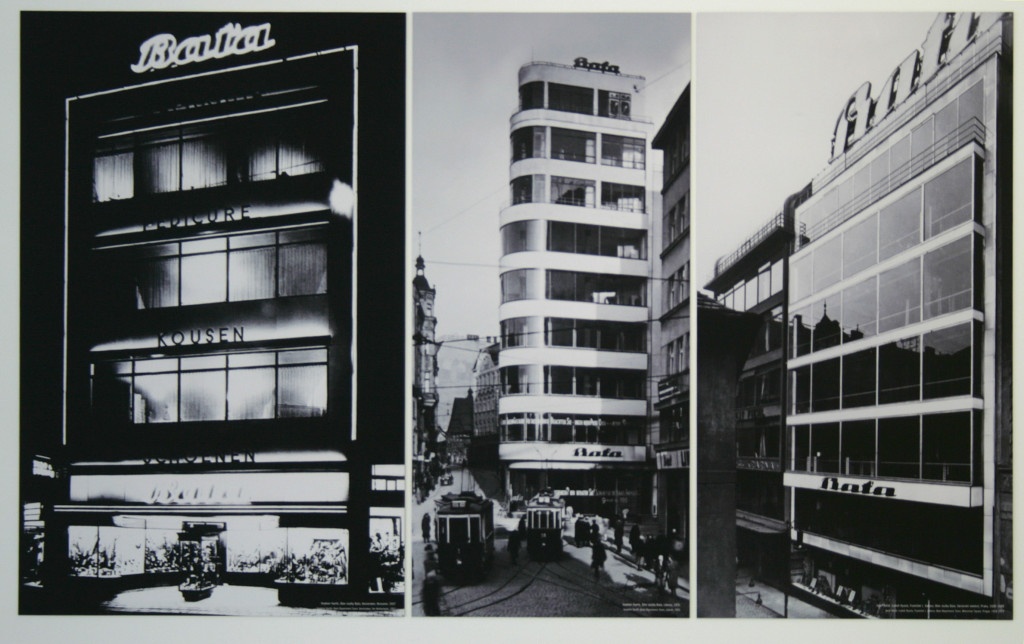

Bata’s shops, photo taken at The Regional Gallery of Fine Arts in Zlín, Zlin 2014, photo Contemporary Lynx

She placed a neon saying ted’ on one of the buildings of the old Bata shoe factory, on the current Bata Art Institute,. On one hand it alludes to the lettering of 1920 which is known all over the world form the brand’s logo. The red ted’ neon is like a signal reminding about the old proprietor and the creator of the emporium – Tomasz Bata. Although the heritage is a bit withered, the centre of its world has been relocated to other places (London, New York, Rio de Janeiro, and currently Switzerland), the old post-industrial buildings and the whole architectural vision of the ideal town aiming to cater for all the needs of the factory worker, is a silent witness of this magnificent design. And Sokolnicka’s red neon is a subtle symbol which shines in the night in memory of the old proprietor.

However, looking from afar it also seems to be a certain critique of the infatuation with the past, of lingering over something that existed 100 years ago. The city itself seems to be breathing the past and to be stuck in it. So maybe it means that we need to turn to the future? If so, maybe we should read the neon as a perverse allusion to the academic conference called ted, which aims to popularise “ideas worth spreading”, those which have the real power to change the world, just like the ideas followed by Tomasz Bata 100 years ago.

The artist’s intention was also for ted’ to highlight THIS moment – the NOW (now in Czech is ted’). So the neon calls us to focus on the here and now. We are not to look back, but actively create the day at hand.

Translated by: Ewa Tomankiewicz