What is the condition of the modern interactive film industry? What are the latest trends? Where can interactive films be used? How to successfully create such films?

The omnipresent interactivity

In the era of new media, one of the characteristic features of visual culture is far-reaching interactivity which everybody gets accustomed to by using social media interfaces, mobile applications and interactive software every day and utilizing state of the art domestic appliances, such as washing machines, or gadgets, such as smartwatches.

The new habits we acquire in this way are the reason why we more and more frequently expect the so-called old media, such as films and television, to be interactive as well. This trend gives rise to new ideas for interactive forms, such as interactive films, which are currently one of the most interesting directions in the film industry. This medium is based on non-linear narration where the viewer influences the course of action and can independently decide how the story of a protagonist or multiple protagonists unfolds or can determine the order and the way in which they get to know the setting. Interactivity in films provides us with new opportunities of building the narration, makes the story told absorb us to a greater extent and allows us to participate in the process of creation by combining the pieces prepared by the director. The examples of the most famous interactive film productions include an episode of the Black Mirror series, namely Black Mirror: Bandersnatch (2018) and the Possiblia (2014) melodrama.

Classic film creators experiment with interactive video content along with filmmakers working in the field of new technologies. Museums and cultural institutions are interested in interactive films as well. For many years they have been investing their financial resources in digital content because they acknowledge the fact that their clients these days are not only those who buy tickets in a ticket office and stroll along museum corridors. They realise that people visiting them are owners of smartphones and users of social media or Netflix fans.

Another kind of institutions eager to discover interactive films are educational organizations. They perceive interactive content as an opportunity to create engaging interactive audiovisual experience for their young audience, which would facilitate learning and memorizing, and develop their critical thinking skills.

What an interactive film really is?

Telling stories is one of the key experiences for humans, which is universal across all cultures. The way in which we tell stories changes because the available technology evolves as well. Every new medium produces a new form of narration.

This principle also applies to films, which have captivated audiences since the late 19th century, becoming the centre and a reference point for contemporary culture. In the 1990s, thanks to the rapid development of new media and advanced technologies, filmmakers and television industry turned towards interactive forms of narration.Nevertheless, we can say that since the very early beginnings of filmmaking, directors have been eagerly experimenting with narration and interaction. It all started with optical toys (thaumatrope). Then came films, such as Mr. Sardonicus (1961) directed by William Castle, which gives the viewer the power to choose the ending of the story told, or Kinoautomat: One Man and His House (1967) by Radúz Činčera. There were also experiments with conventional manners of storytelling by Jean-Luc Godard, Michael Haneke and Woody Allen.

The latest interactive audiovisual narrations, such as the already mentioned Bandersnatch and Possiblia, are projects focused primarily on the typical components of films, namely acting, dialogues, camera work and montage. All these components are enriched with interactive elements, which means that from time to time it is the viewer who determines the course of action and the fate of the protagonists.

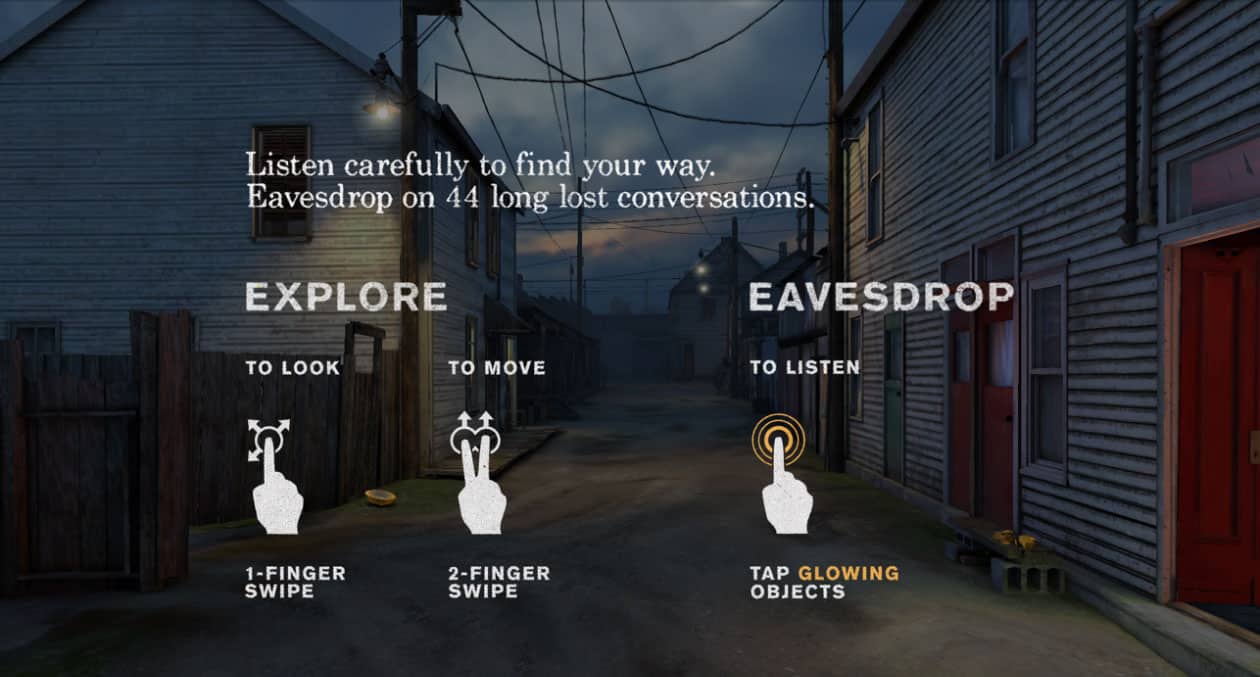

On the other hand, interactive documentaries are also considered interactive films, since they provide the audience with interactive audiovisual narration as well. An example of such film is National Film Board of Canada and New York Times 2013 production “A Short History of the Highrise” (dir. K.Cizek) which combines New York Times archives and multiple media into a single, long-lasting project about the architecture of tower blocks. The augmented reality application “Circa 1948”, which reconstructs the no longer existing districts of Vancouver (also produced by NFB in 2014) is also worth mentioning here.

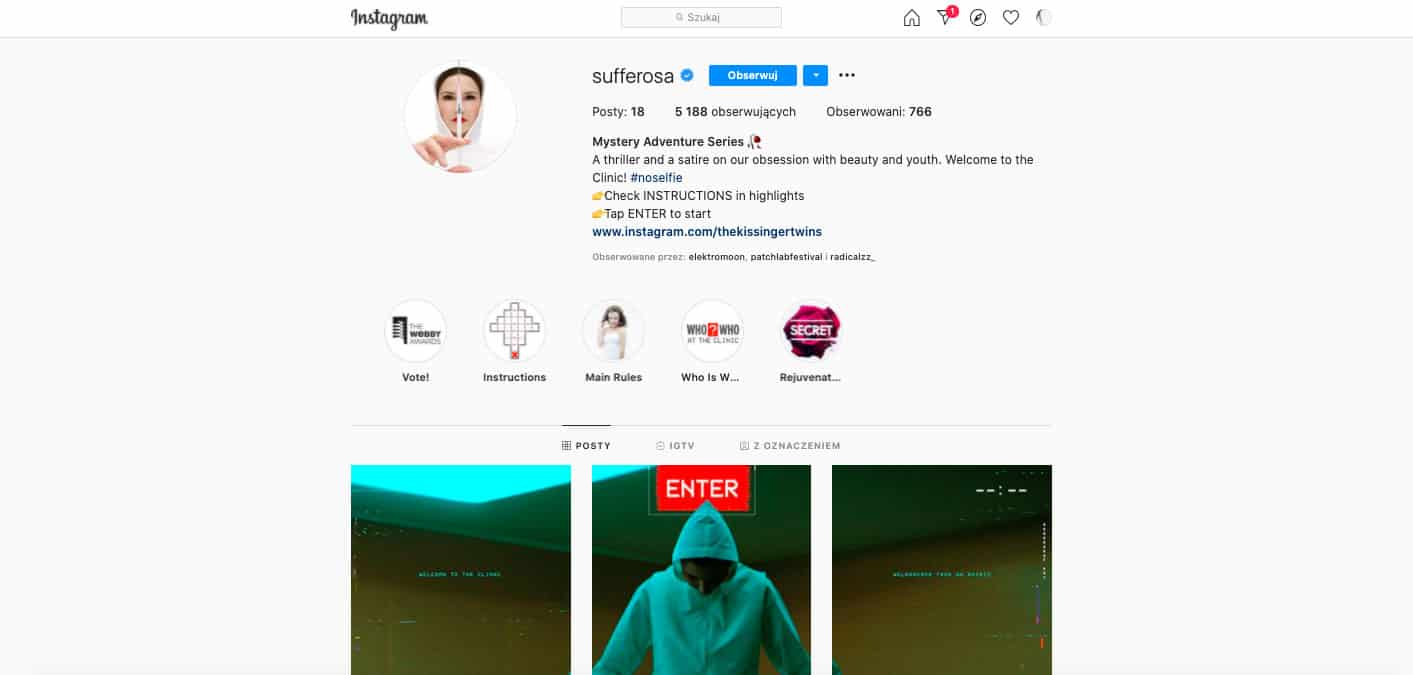

An interesting example of the kind of interactive audiovisual narration called an internet-born narration is Sufferrosa – a thriller which derives a lot from the neo-noir genre, a satire on the cult of youth, which at the same time is an innovative interactive online project combining film, literature, music and social media. The project was created in 2019 in Instagram by The Kissinger Twins, the creative duo who won this year’s edition of The Webby Awards, which can be compared to Oscars awarded for excellence on the Internet. Transmedia project “The Trip” is yet another example of interactive narrative created by the same artists. It invites us on a nostalgic journey through the history of cinema, vast areas of the United States right up to the moon. The entire narrative was created using the found-footage technique, i.e. by combining parts of other films.

Another documentary feature which utilizes social media, their responsiveness and interactivity, and presents an audiovisual narrative to the viewers is “Temporary Contact” (2017, by Nilit Petred and Sara Kostler). In order to watch it, you need to log into the Messenger app and use the chat to follow the journey of women who visit their relatives being prisoners in a penal institution in the US. During the journey the story of these women unfolds itself through subsequent messages which we receive.

The fact that the projects described above are so diverse proves that an interactive audiovisual narrative can be successfully created using different techniques and adopting different approaches. This is exactly why it is so difficult to define this new, constantly developing medium. If you are interested in this topic, we recommend the Polish publication “Kino interaktywne – porządkowanie pola” (2015) by prof. Ryszard Kluszczyński.

Apart from exploring the possibilities offered by new media, experimenting with non-linear storytelling is also about looking for an answer to the question on our perception, which is so interesting to psychologists and neuroscientists. How do we perceive stories and how do we understand them? Does our brain process them in a linear manner and follow the defined order from the beginning to the end? Maybe it is just the opposite and we process stories through associations, references, in other words, as hypertext? It has been widely confirmed by research that we learn and memorize better when we engage multiple senses simultaneously, including touch, hearing and sight. For this reason interactive films, or in general, interactive audiovisual narratives are aimed at activating the audience and stimulating them to become more engaged. They encourage us to make choices actively, they offer customized experience and a possibility to immerse ourselves in subsequent layers of content. Just as Krzysztof Kieślowski said, “not to go further, but rather deeper into the story told”.

How to make interactive films?

As we already mentioned, interactive film is a medium that has not been extensively studied yet, mainly due to its innovative form, which does not correspond to any particular genre. There is still a lot of room for research by creators of classic films and filmmakers working in the field of new technologies. There is a need for understanding this form better because there are quite different challenges while making interactive films at all stages – pre-production, production, post-production and promotion – than in the case of traditional films.

Since the very beginning of the creative process, interactive films require a distinct approach to narration, the production process and, last but not least, to the viewers. Let’s begin with narration. Sandra Gaudenzi, the world-renowned expert in the field of interactive stories advises the creators to approach a digital story like a space into which they invite their audience. In this space it is much more important what a viewer can discover in the story, what is the structure of the space and how he can move around than what the next chapter is. Whenever a creator chooses an interactive narrative, he needs to be aware of the reasons for such a choice since the very beginning of the process.

In order to build an interactive narrative it is important to think it over and design its flow. This process is similar to designing computer games, applications and websites.

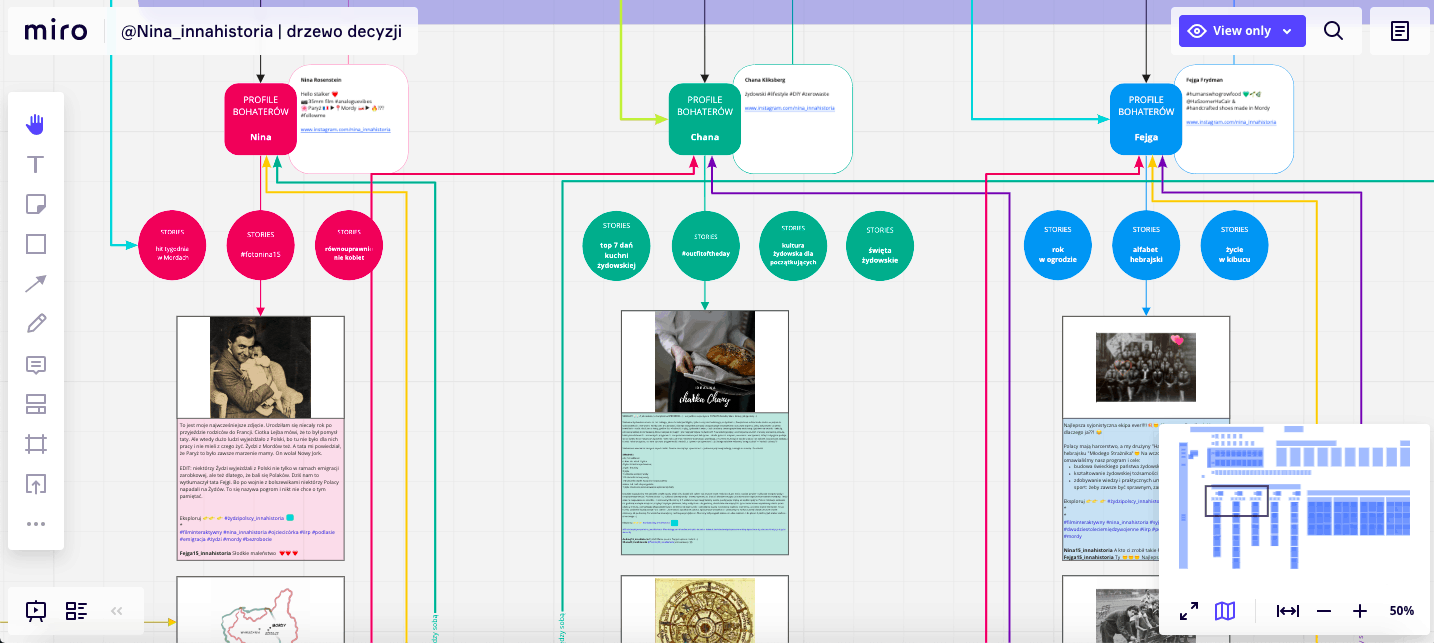

Nina_theother_story – fragment of FilmHack winner interactive film prototype by Cewet Tow team, 2020

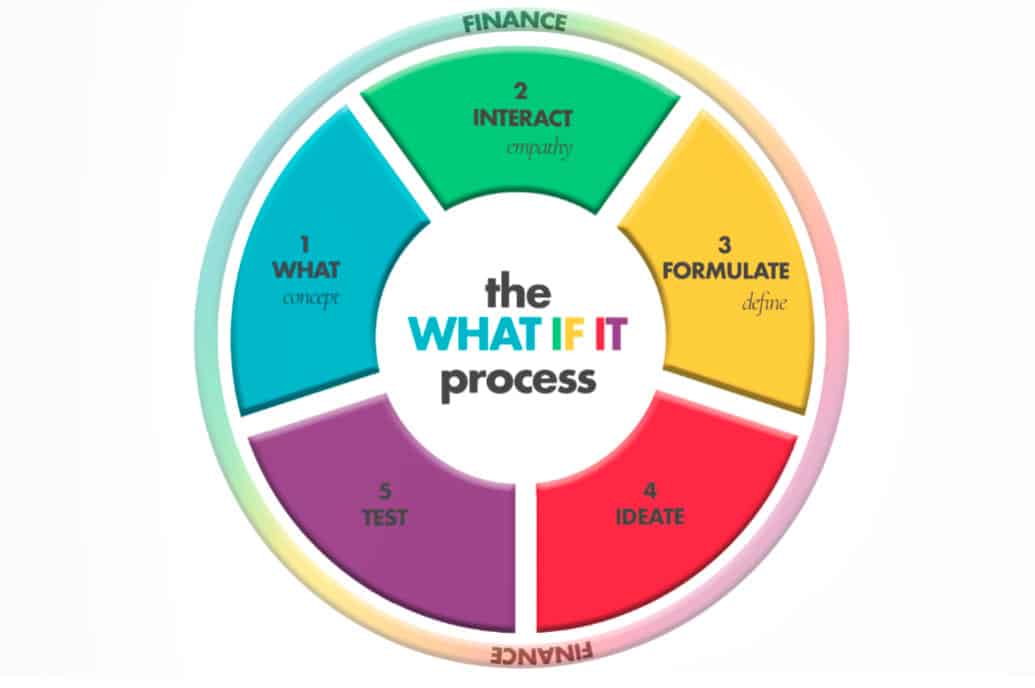

Flow must be visualized at the early stage of working on a concept in order to be tested with users, based on iterative methods of design used in new technologies, such as design thinking. The process is similar to digital tools design in that it is worth to make a prototype using analogue techniques, on a sheet of paper, for example using printed photos which symbolize the footage. They can be connected with arrows depicting interactions and relationships between separate scenes and protagonists. This may be a primitive form, but it allows for quick corrections and modifications to the original idea without losing the precious time, immediately after carrying out the tests with viewers. Such approach requires creators of interactive narratives to be flexible and to apply design thinking principles, which are about close cooperation between a designer and a recipient at every single stage of creating and developing a product. This is the aspect that may be difficult for those who create classic linear narratives.

How is it done today?

There are various institutions which experiment with interactive audiovisual narratives following the philosophy of combining the world of design, new technologies and film. One of them is New Frontier Lab, a part of the Sundance Institute (an organizer of the Sundance Film Festival).

There are also such centres in Poland, for example Laboratorium Narracji Wizualnych: vnLab at Lodz Film School and Pracownia 3d i Zdarzeń Wirtualnych at The Academy of Fine Arts in Warsaw.

One of the experiments which went even a step further when it comes to creating interactive film narratives was FilmHack – Interactive Film Hackathon organized by Ośrodek KARTA. The aim of this project was to explore the possibilities offered by this medium for education in the field of history. We, the authors of this article, had an opportunity to participate in this project. The partner of this event who provided expertise in the field was the above-mentioned Laboratorium Narracji Wizualnych: vnLab. Due to the COVID pandemic, the entire event was held online.

FilmHack was designed as a participatory lab allowing the creation of interactive audiovisual narratives. Its aim was to create an opportunity to explore the possibilities offered by this medium when used as a tool in education. The project not only utilized methods and solutions known in the film industry, but also the latest technologies (design thinking, user experience).

The event was organized in the form of a hackathon (or a hacking marathon) which involves project work in interdisciplinary teams, therefore it encouraged scriptwriters, UX designers, directors and animators to equally contribute to the development of interactive audiovisual narratives. It was the first experience with interactive film for most of the participants, therefore they were supported by mentors who are creators and experts in various fields related to film and technology.

A hackathon is format willingly used when it comes to new technologies. Hackathons are organized when innovative services and products need to be designed, but they are also frequently selected as a format for events in film industry (Exposure Science Film Hackathon) and culture (HackArt, hackathon MNW, Hackathon Archiwalny NAC).

The task for the FilmHack participants was to create a concept of an interactive educational film for adolescents, which would be based on archival materials related to the relationships between the Poles and the Jews in the 1920s.

A real-time online hackathon took place in late May and early June 2020. It became a platform for exchange of knowledge and good practices between the participants and mentors who work with traditional films and those who work with new technologies on a daily basis. The teams managed to achieve a synergy effect. They combined methods, techniques and tools known in the field of film and IT and, in a relatively short time, created prototypes of interactive audiovisual narratives, tested them with viewers and presented them to the jury. It is worth mentioning that creators of interactive films often need long months, sometimes even years, to create their concepts. Therefore the results of the FilmHack which were produced by all teams were a very positive surprise.

The FilmHack jury (including the Kissinger Twins, Bartosz Konopka – a director who was nominated for an Oscar, Kamil Pohl – a director working with Platige Image, Bartosz Borys (Jewish Historical Institute), Anna Wilk (Media School Foundation) and Alicja Wancerz-Gluza (Ośrodek KARTA)) awarded three very different concepts which represented various trends and approaches to interactive films.

- An Instagram series presenting an interactive story about teenagers, entitled Nina_inna historia (Cewet Tow team)

- Chejt film (“a sin” in Hebrew) in a style of noir comic books with built in historical documents and animations presenting events from history (Game of Docs team)

- The film Przejdź do historii (created by the team with the same name) combining fiction and 360-degree technology, which plot revolves around two young protagonists who embark on a search for a mysterious bundle.

Ośrodek KARTA intends to build on these projects and strengthen the community of creators of interactive films based on historical facts. They can now interact with one another through a dedicated Facebook group.

FilmHack was a unique event, not only due to its subject and methods of work, but also because it was a fully online event taking place in real time. This involved everyday intensive meetings over a relatively short period of time. Thanks to such format we were able to gather all participants, mentors and jurors, make work on concepts run smoothly and recreate the atmosphere of a hackathon organized in a non-virtual reality. The challenge which participants had to face was even greater because they needed to base their narrative on archival materials about the history of the relationships between the Poles and the Jews before the war, which KARTA has been collecting singe the 1990s.

The choice of interactive film as the medium was by no means a random choice. This audiovisual and interactive form engages multiple senses, which aids learning and memorizing, triggers empathy, awakens an interest in stories from the past and makes the audience sympathize with the fate of the presented protagonists.

Are we ready for interactive films?

Despite a significant popularity of such productions as Black Mirror: Bandersnatch which we already mentioned, interactive film is a genre which is not well-known to the general public. Some people perceive it merely as a curiosity, an undefined hybrid between role-playing games and films.

When it comes to young viewers who took part in the testing of prototypes created by FilmHack participants, they could only understand this medium after being provided with extensive explanations on what interactive films are and several examples. This allowed them to see the advantages and limitations, nevertheless they still continued to compare interactive films to role-playing games.

There were dead-end streets of evolution in the history of media with media which were supposed to captivate our imagination being displaced by forms that were easier and cheaper to produce and distribute. Producing an interactive narrative based on a feature film is certainly very costly. The budget encompasses not only the costs of creating a film (which is often much longer than a standard film due to a large number of paths or permutations). There are also costs of the project itself, the creative work, dialogues and enhancing a prototype. The costs increase if we opt for 360 degree videos, virtual or augmented reality technology or artificial intelligence.

Nevertheless, it is increasingly easier to create interactive audiovisual narratives thanks to the development of the internet, social media and intuitive software which allows their creation. Everybody can become a creator of such narratives if they are willing to use their imagination.

We are accustomed to familiarizing ourselves with new content in an interactive way thanks to hypertext that is omnipresent in new media. The ability to quickly switch between various content is something we literally take in with our mothers’ milk. This is why the future of interactive films is in our hands, speaking both literally and metaphorically.

Written by Sylwia Żółkiewska and Ewa Drygalska

Cooperation: Agnieszka Kudełka, Ośrodek KARTA