Franciszka & Stefan Themerson: Books, Camera, Ubu is on show at the Camden Arts Centre until 5 June 2016. The exhibition’s title provides a handy guide to its three parts, documenting the main areas of the Themersons’ innovative and diverse practice that spanned six decades.

Born in Poland at the beginning of the 20th century, in Warsaw and Płock respectively, Franciszka and Stefan met in Warsaw in 1929 and got married in 1931. They became pioneers of the Polish cinematic avant-garde, co-founding the Polish Film-makers’ Co-operative in 1935. Their three surviving films are presented in the ‘Camera’ section of the show, in Gallery 2 (A reconstruction of Europa, 1931/32, is screened in the Reading Room). The Adventure of a Good Citizen (Przygody człowieka poczciwego) from 1937 is presented as an ‘irrational humoresque’. It starts with the Good Citizen’s insistence on walking backwards, which triggers a militant demonstration protesting such freedom, all portrayed in a series of delightfully surreal sequences. I hope the refreshing playfulness of the film makes it captivating, even for those who don’t understand the intertitles or the slogans written on the banners, as the film is not subtitled.

Franciszka and Stefan Themerson, The Adventure of a Good Citizen, 1937 . Film stills, © Themerson Estate, London

The Themersons moved to Paris in 1938, but both volunteered for the Polish army after the war broke out in 1939 and were reunited in London only in 1942. Their 1943 film Calling Mr. Smith was banned in Britain, because of its accusation against Hitler’s Germany of the destruction of Polish culture. The Eye and the Ear (1944/45) is a poetic essay on the relationship between image and sound, with eerie moving photograms (photographs without film) arranged to a soundtrack of Karol Szymanowski’s music. There are stunning sequences of the surface of water, disturbed by drops and hands, illustrating Szymanowski’s song ‘Wanda’, which is a tribute to a legendary Polish princess, who threw herself into the river to avoid an unwanted marriage. Stefan’s creative journey started with his experiments with the camera, and his early photograms and photomontages are exhibited alongside film stills, and a later image of the artist’s trick table, from 1983.

Franciszka and Stefan Themerson, The Eye & The Ear, 1944/45. Film still, © Themerson Estate, London

Gallery 1 hosts the ‘Books’ section. Even though chronologically, the camera came first in the Themersons’ creative practice and collaboration, it was for their books that the couple was initially known in Britain. After making London their home in the middle of World War Two, the couple started a publishing house in 1948 called Gaberbocchus, named after a spoof Latin translation of Lewis Carroll’s Jabberwocky. The press aimed to create ‘best lookers rather than best sellers’, and so the design of each book matched its often experimental content. Firmly rooted in the European avant-garde of the 1930s (in the words of Nick Wadley, an art historian and a friend, they were ‘great respecters of nonsense’), they published English translations of works by its prominent authors (Kurt Schwitters, Guillaume Apollinaire, Alfred Jarry) and first editions by English authors (Bertrand Russell, Stevie Smith). Owning a press gave them the freedom to publish their own work exactly the way they wanted, and some of the editions of Stefan’s books are on display alongside the works by other authors.

There’s a lot to take in here (including the press’ promotional materials), but the process is never boring as designs are bold and beautifully executed (including a facsimile reprint of Europa, Anatol Stern’s first Polish futurist poem, on which the 1931/32 film is based). Some of Franciszka’s humorous cartoons are thrown into the mix, and Stefan’s semantic poems are printed directly on the walls. These have a very contemporary feel to them (and work well as a prelude or companion piece to the text-based exhibition of contemporary Swedish artist Karl Holmqvist, taking place in Gallery 3) and seem very popular with visitors: I couldn’t help myself instagramming the 1960 LIFE-TIME poem: “it takes a minute to count a minute and the time spent counting doesn’t count” on the spot.

In 1951, Gabberbocchus Press published the first English translation of Alfred Jarry’s era-defining play Ubu Roi, which became a source of creative inspiration for Franciszka for years to come, as documented in the ‘Ubu’ section of the exhibition. She designed an award-winning production of Kung Ubu for marionette theatre in Stockholm (1964), and masks for a reading of the play at the Institute of Contemporary Art in 1952. Between 1969 and 1970 she drew a comic strip based on the play, and the original drawings hang on the walls in all their one-metre-long glory, putting the cruelty of Ubu into perspective.

The Themersons’ experimental films and photograms strike as innovative and groundbreaking, even in an age where artists and filmmakers have the tools of the Adobe Creative Suite at their fingertips.

In the video interview accompanying this exhibition, Nick Wadly, a curator of the Themersons Archive, describes how popular Gabberbocchus Press’ events are with young audiences; where students are drawn to the books’ materiality, to print on paper in the world when the immaterial digital realm seems to be on the verge of taking over. While going back to making, to material, is definitely one of the ways contemporary viewer can engage with this body of work, it would be wrong to assume this show comes only from a sense nostalgia for times past. The Themersons’ experimental films and photograms strike as innovative and groundbreaking, even in an age where artists and filmmakers have the tools of the Adobe Creative Suite at their fingertips. After seeing this exhibition, it is difficult to disagree with the Archive’s co-curator Jasia Reichardt, who asserts that the Themersons “would have espoused digital culture as well”. Indeed, it would be exciting to see how they would incorporate the use of state-of-the art digital technologies into their rich practice, permeated as it is by the spirit of improvisation and seemingly always being half a step ahead of its time.

words: Ania Ostrowska – a film editor, and writes in ‘The F-Word’, a British feminist blog. She is also a doctoral researcher of British women documentarians, at the University of Southampton

Kung Ubu, directed by Michael Meschke at the Marionetteatern, Stockholm, 1964. Costumes and puppets designed by Franciszka Themerson, © Themerson Estate, London

Puppets by Franciszka Themerson for KUNG UBU, Marionetteatern, Stockholm, 1964, Photo: Valerie Bennett, courtesy of Camden Arts Centre

Stefan Themerson, collage of Franciszka and Mère Ubu, 1969/70, © Themerson Estate, London

Puppets by Franciszka Themerson for KUNG UBU, Marionetteatern, Stockholm, 1964, Photo: Valerie Bennett, courtesy of Camden Arts Centre

Installation view of Franciszka & Stefan Themerson: Books, Camera, Ubu, Camden Arts Centre, 2016, Photo: Valerie Bennett, courtesy of Camden Arts Centre

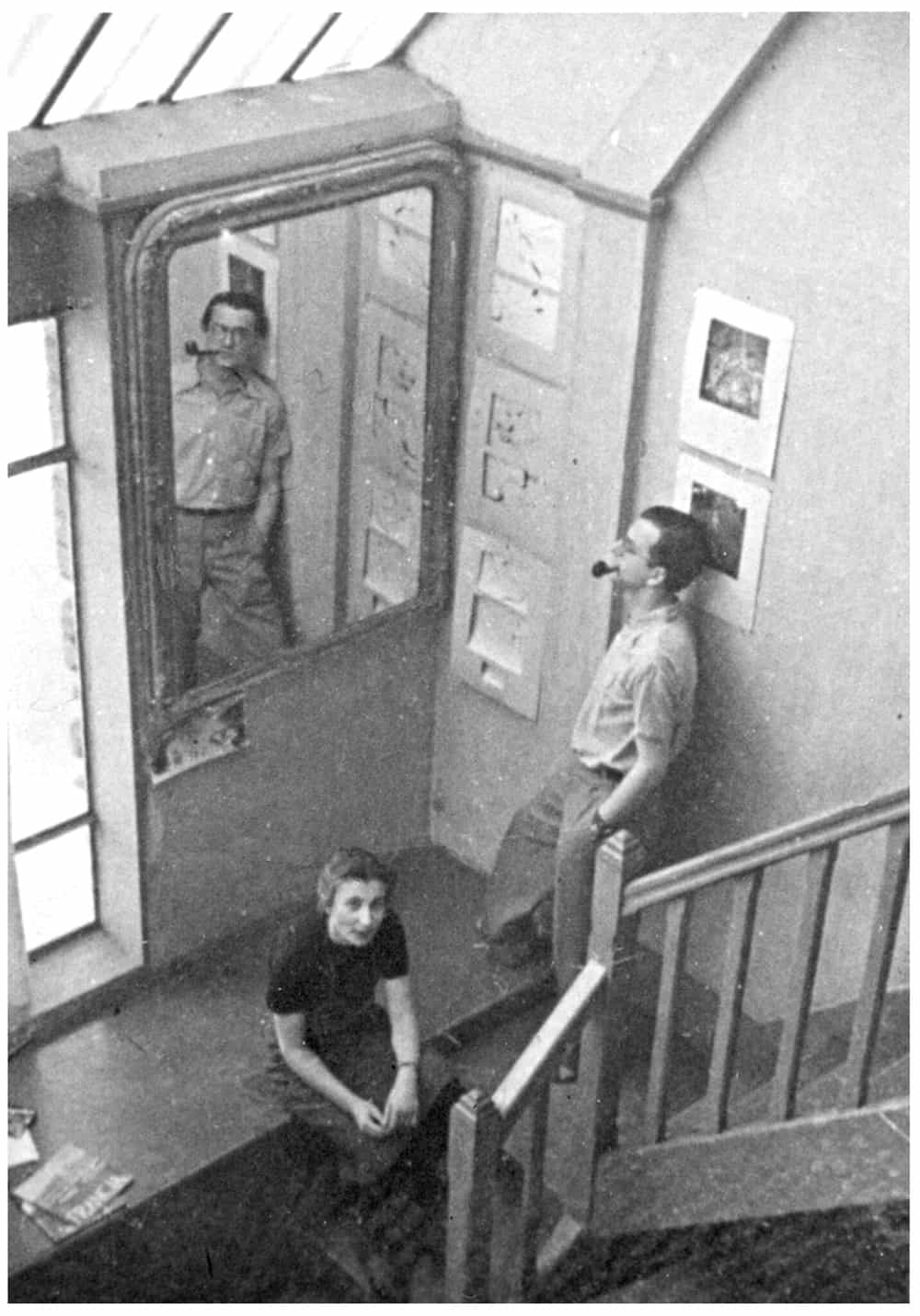

Franciszka and Stefan Themerson in their studio, Paris, 1938, © Themerson Estate, London