A disintegrating exhibition poster. Edward Krasiński’s studio apartment, Warsaw, Poland, 2016

Ahead of his major retrospective opening this week at Tate Liverpool, we visit the lovingly preserved former studio and home of Polish artist Edward Krasiński — uncovering ostrich eggs, VAT receipts, blue Scotch tape, toy mice, and all…

The rickety lift opens at the top floor, and there he is: sculptor Edward Krasiński (1925–2004). It’s a to-scale photograph printed onto his front door, but it’s him nonetheless, welcoming us. There’s refurbishment work going on, so someone’s covered him from head to foot in bubble wrap. He’s holding his hands up through the plastic, smiling; as if to say: “Hey, what can you do?”

We’re lucky enough to be visiting Krasiński’s studio apartment. Situated at the top of an unassuming white, orange and grey tower block on Solidarnosci Avenue, in Warsaw, Poland, the artist’s home has been meticulously preserved since his death. We wanted to visit this time-capsule in person, to learn more about the man before a major new look at his life and practice back in the UK at Tate Liverpool (21 October 2016–5 March 2017). What type of artist was Krasiński? According to Tate, he is one of the most significant Eastern European artists of the 20th century; his work seemingly dominated by minimal, geometric paintings and installations covered with blue tape. Originally from Łuck, now Ukraine, Krasiński was also at the heart of Warsaw’s complex, state-sponsored art scene throughout the 1950s-70s; co-founding, and later distancing himself from, the city’s Foksal Gallery.

It’s something Foksal Gallery Foundation (FGF) art historian Aleksandra Ściegienna can tell us more about. She’s our guide today, as the FGF were set up by a new generation in 1997 to look after the archive of the original Foksal Gallery, and this studio.

A collection of photographs and postcards. Edward Krasiński’s studio apartment, Warsaw, Poland, 2016

“A bright blue line of vinyl Scotch tape is positioned at heart height, working its way horizontally across walls, doorframes, curtains and mirrors”

The building is a 30 minute walk from the city centre, through attractive streets punctuated with theatres and small parks. In contrast, Krasiński’s studio is silent, aged, and dusty with fragile-looking artefacts collected over a lifetime. Paintings, sculptures and clusters of trinkets and found objects are arranged exhibition-style on surfaces, wherever Krasiński placed them: in small groups on the wooden floor and dining table; on book shelves, walls and window ledges. Ordinary items like VAT receipts, letters, photographs and postcards are given display space equal to more unusual items, like an ostrich egg, an artificial Christmas tree with blue ribbons, a typewriter with one spiky red key, and some moth-eaten toy mice.

One major feature gives away the homeowner: a consistent and bright blue line of vinyl Scotch tape is positioned at heart height, working its way horizontally across walls, doorframes, curtains and mirrors; dividing the apartment into two halves.This signature Krasiński drawing material has the strange effect of animating the whole space; connecting all the things it adheres to, and encouraging the eye to follow. Of the tape, Krasiński noted in a 1977 exhibition catalogue: “IT intervenes IN and unmasks EVERYTHING. IT exists. I trust IT.”

“Krasiński used to work at night, to keep his process a mystery; so works would just ‘appear… like a creation… like a magician’”

His work is best described as “spatially dynamic”; using his blue tape — along with mirrors and photography — to create new dimensions. In exhibitions, Krasiński’s 2D canvases conjured up 3D rooms and building-blocks from blue and black lines; his sculptures were suspended in space on barely visible wires, and without the use of plinths (and sometimes in parks and green spaces).

Despite a rather serious art practice, Ściegienna describes Krasiński as having a great “sense of fun”. At home, this can be seen by work popping out – literally – of the floor and ceiling. You really have to watch your step. We nearly trip over a branch which is growing out of a crack in the floorboards. Ściegienna says that Krasiński used to work at night, to keep his process a mystery; so works would just “appear… like a creation… like a magician.” Nearby, a slim, gravity-defying metal pole punches vertically through the floor, and an afore-mentioned little fluffy mouse runs up the side; a joke to make his work seem less serious. Krasiński’s fist-sized wooden cubes (from his Object series (1960s)) pasted with photographs and tape, hang from wires at various points in the apartment; a playful display of smiling faces that slowly turn in the air.

The entrance to Edward Krasiński’s studio apartment, Warsaw, Poland, 2016

In the dining-room-cum-workspace-cum-bedroom, an accumulation of all these ideas appear quite theatrically on one wall: three white canvases are hung in a row, depicting rooms with black painted lines, and the cubes hang freely in front. All are connected with zigzag, blue tape. It is this arresting relationship between object, space and the beholder that makes Krasiński, according to Tate Liverpool Senior Curator Kasia Redzisz, “a director of a spectacle rather than merely a sculptor. A master of ceremony, an illusionist deceiving our eyes, a conductor responsible for harmony of experience.”

To know that Krasiński studied interior and graphic design, and then painting, in 1940s Krakow, and worked as an illustrator and set designer when he moved to Warsaw in 1954, is some insight into his skills as “a director of a spectacle”; adept at imagining, drawing and building products that would be navigated by others. Constructivism, Dada and Surrealism inspired him and his art school peers in Krakow – as seen in the abstract set designs of Tadeusz Kantor, and grotesque paintings of Tadeusz Brzozowski.

“It was his friendship with ground-breaking Constructivist painter Henryk Stażewski (1894-1988) that can be said to have had the biggest impact on Krasiński’s life”

However, it was his friendship with ground-breaking Constructivist painter Henryk Stażewski (1894-1988) that can be said to have had the biggest impact on Krasiński’s life. Stażewski was a respected artist with influential friends (including Modernist icon Kazimir Malevich), and 30 years Krasiński’s senior. It was also his penthouse on Solidarnosci Avenue that Krasiński often visited and eventually moved into in 1970, invited to stay by the older artist when Krasiński’s marriage to the critic Anka Ptaszkowska broke up. Stażewski liked to entertain; our guide, Ściegienna, tells me that Warsaw’s artists, gallerists and critics would come to listen to Stażewski hold court. So little photographic documentation from this time exists, she says, as no one dared interrupt Stażewski’s flow to take a photograph. After his death in 1988, Krasiński took down Stażewski’s paintings but left the hanging wires up; they’re still drooping down, along with the canvases’ shadows, like ghosts of Stażewski’s work.

Crucially, Krasiński and Stażewski were also co-founders of the Foksal Gallery along with six other artists and critics, including Kantor and Krasiński’s wife Ptaszkowska, in 1966. Just four years later, Krasiński, Ptaszkowska and Stażewski left Foksal under a storm cloud of major disagreements with the rest of the co-founders, about the artistic direction that Foksal was taking. At the time, Ptaszkowska couldn’t bear the tension, and moved to Paris, alone. Krasiński moved in with Stażewski, but had lost a key exhibiting space; feeling the impact more deeply than his established mentor. Krasiński was then asked to represent Poland in the 1970 Tokyo Biennial; the show ended up marking what some consider to be Polish art’s first conceptual action. He telexed the word BLUE — repeated 5000 times — which reached the organisers as a 80-metre long strip of paper (later placed in a bullet-proof glass case), plus his previously tested blue Scotch tape. “The artist wants things impossible”, noted the writer Andrzej Kostołowski at the time; “he wants to suggest infinity in a visually perceptible manner.” The tape reappeared in his show at Musée d’Art Moderne in Paris later that same year, and continued to appear Krasiński’s exhibitions thereafter.

“Krasiński’s apartment is a treasured reminder of his life and complex practice”

Now, Krasiński’s apartment is a treasured reminder of his life and complex practice; his significant friendship; and the fact that the studio became a fundamental exhibiting space after his tense falling-out with Foksal. We discuss the preservation of the apartment in comparison with Flat Time House: the studio home and “living sculpture” of British Post-war artist John Latham (1921-2006), who used to open his door, as Krasiński and Stażewski did, to anyone interested in discussing art. The future of this Warsaw tower block is uncertain, and Ściegienna and Foksal Gallery Foundation cannot say what will happen to it in the future. It will be preserved for as long as possible, but what if the building is earmarked for demolition? It seems unlikely that a “recreation” would be in keeping with the spirit of the place; and the studio is potentially too brittle for an intervention along the lines of Roger Hiorns’ Seizure – in which his entire, crystallised London council flat was sliced out in one piece, and transferred to Yorkshire Sculpture Park. The best example of the fragility of the studio’s contents is on the living room floor: a disintegrating poster emblazoned with “EDWARD KRASIŃSKI INTERWENCJA”, warped with moisture, and weighed down by four eggs. It’s a sad reminder of the temporality of life, and the legacy that one would want to leave.

The lasting memory from our visit, however, is the atmosphere. The Krasiński studio is unlike anywhere we’ve ever stepped foot into. The artist lived here, laughed here, created and thought here; ate, drank and entertained here. Everything — from marks on the walls, to a cup with evaporated tea stains – has been carefully, respectfully preserved. It’s a special place and one which would be impossible to replace. Leaving the apartment and silently saying goodbye to Krasiński’s smiling face on the door, we wonder what he would have thought of this time-capsule, this tribute.

Written by: Laura Robertson

This article was originally published on The Double Negative: an artist criticism and cultural commentary journal based in Liverpool, UK.

Laura Robertson – is a freelance art critic based in Liverpool. She is editor and co-founder of http://www.thedoublenegative.co.uk/.

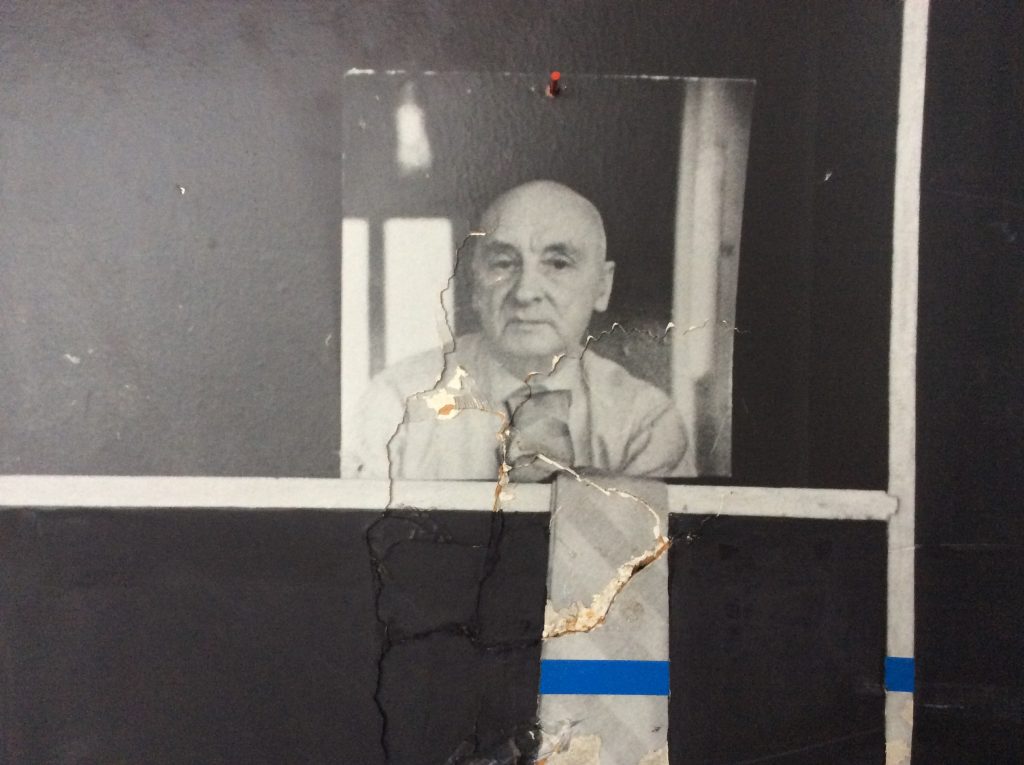

A photograph of Henryk Stażewski, with blue-taped tie. Edward Krasiński’s studio apartment, Warsaw, Poland, 2016

PrevNext

Edward Krasiński’s studio apartment, Solidarnosci Avenue, in Warsaw, Poland, 2016

A toy mouse runs up a cupboard door. Edward Krasiński’s studio apartment, Warsaw, Poland, 2016

Edward Krasiński’s studio apartment, Warsaw, Poland, 2016