Jan Manski was interviewed by Monika Waraxa during the private view of his latest exhibition Possesia at London-based gallery BREESE LITTLE on 26 February 2014.

Jan Manski, Idol III, 2010 / 100 x 70 cm (39 3/8 x 27 9/16 in) colour photograph, soil, steel, photo courtesy of artist

Monika Waraxa: Why did you wear long black boots on the private view?

Jan Manski: Possesia is a tale that refers to authoritarian regimes. The boots are a souvenir from a friend in Moscow, so I think that speaks for itself.

MW: How would you describe what you do to an elderly lady who is your friend`s well-read grandmother?

JM: Generally artists don’t like to describe their work. I’m no exception. I prefer to read reviews by others. I think the work should speak for itself and a rational description is never enough To put it literally: I’m a multidisciplinary artist working in sculpture, film, oil paint and collage techniques.

MW: What is Possesia? Is it a part of some bigger piece?

JM: My goal is to build a multidisciplinary series that refers to art, history and mythology. Possesia is the part that addresses Europe’s violent history, Onania parodies our consumerist culture and Eugenica will depict the future of gene engineering.

Jan Manski, Installation View, paintings, horseman, photo by Tom Horak, Breese Little Gallery, London 2014

MW: Did you follow the plan or rather grasp digressions when working on Possesia?

JM: There were some major subjects and the forms grew naturally. Layer-by-layer it became what it is. The most exciting part was improvisation, but according to pre-planned commitments like choices of groups of materials that define the series’ aesthetic. All the motives are connected, but they are like unfinished sentences, it’s like a narrative without a linear story. Its open structure allows for constant change.

MW: Where was Possesia was made?

JM: When I was working in London I realised that I need constant access to Polish flea markets as they are very rich in objects that are impossible to get in the UK. So this project was mainly made in my Warsaw studio.

MW: The greatest pleasure and obstacle when working on this cycle?

JM: The hardest task was the preparation, it was a really time consuming process. The greatest pleasure was to have all the objects in one place then I was able to look for the best possible assemblages.

MW: What was the oddest opinion on your art works?

JM: I don’t have a recollection of the most extreme, but I remember one that was really interesting. A journalist in Estonia wrote that Onania’s mutated faces ‘remind of an aristocracy punished for their ignorance’.

MW: What is your workshop like? How do you work?

JM: There are no limits in my ways of building the work. I often start with found objects and re-make them. It’s a mysterious process – we will never know how inspiration brings ideas to life. It’s like the process of biological growth, we can analyse it, name substances that cause it and watch it, but we are unable to define the power behind it.

MW: What does war mean to you?

JM: I grew up in the eighties in Poland. It was the end of the regime, an isolated state fed up with war films, while not free from propaganda. I think it shaped the worldview of my generation.

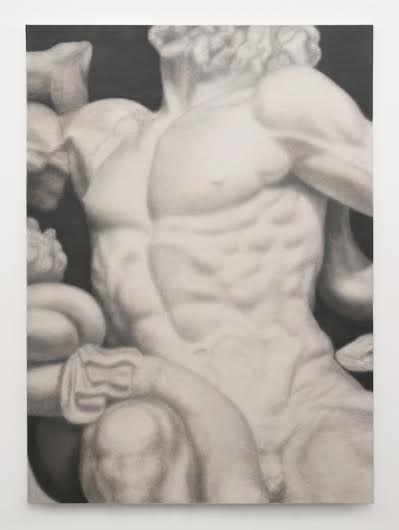

Jan Manski, Marble 2014, oil on canvas, 165 x 120 cm, image courtesy of artist

MW: What does black symbolize to you?

JM: For me, black joins all the elements here in Possesia. It’s the colour of soil and tar. Apart from its most common meanings of grief and strength, there is also the most famous uniform design in history – Hugo Boss’ Gestapo uniform.

MW: Can death be aesthetic?

JM: In ancient Greece there was an idea that beauty equals truth. There is a scene in Sam Mendes’ American Beauty when a character films a dead pigeon ‘because it is beautiful’. I think the understanding of this scene divides people to those conscious and those not. As a culture we are accustomed to marginalising death and we prize the cult of material things. We tend to see beauty in ornaments, in artificial masks that hide the fear of vanity.

MW: Why did you enclose Witkacy`s portrait in Possesia. What this character means to you?

JM: Witkacy was one of the most progressive artists in Poland of the pre-war period. He was a painter, poet, photographer and philosopher as well. His psychedelic pastel works in particular are ahead of his time. He was conscious of the danger coming from the East. He knew that when the Russians crossed Polish borders they would stay there. He committed suicide in 1939 when the Soviets invaded Poland. He is one of the Idols that appears in Possesia. As Friedrich Nietzsche, he personifies fatalism and genius on the border of insanity.

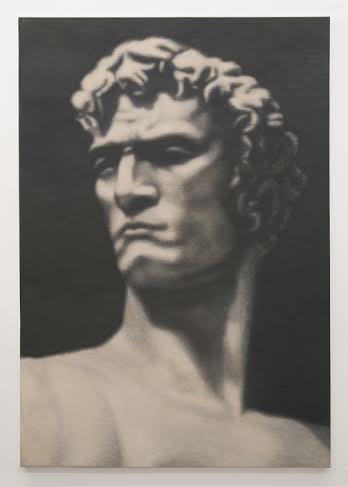

Jan Manski, Idol VII 2013 oil on canvas 120 x 90 cm photo by Tom Horak

MW: Why is the horse wearing suit and sitting inside the cage?

JM: Possesia does not have one defined meaning. As each of its pieces, Horsemen VII is a vision, a realised hallucination. The intellect has no measures to effectively analyse it. You can read it in your own way. It doesn’t have one defined symbolic meaning, but is built on subconscious meaning and archetypal metaphors.

Jan Manski, Horseman VII, 2012 / 223 x 188 x 128 cm, horse skulls, wild boar fur, cow leather, blazer, shirt, tie, antique wheelchair, polyvinyl acetate, resin, vintage mannequin torso, old floor segments, steel cage, enamel, soil, photo by Tom Horak

MW: What fascinates you in prosthesis?

JM: The vintage prosthesis are precisely detailed and beautifully crafted. These hand made objects have a very unique, functional beauty. The marks of previous use make them even more interesting. Objects used in constructing the Possesia world introduce the history of its previous owners and recall the times they witnessed.

Jan Manski, Idol I 2013 / 86 x 200 x 86 cm leather, found army boot, prosthetic leg, manequin parts, bones, found machinery, polyvinyl acetate, soil, fur, horn, vitrine, photo by Jan Manski

MW: Was Arno Breker a good sculptor?

JM: He was a Nazi sculptor that put the Aryan ‘ubermensch’ into sculptural form. It is impossible to read him out of this strong context. His sculptures like Leni Riefenstahl’s films define the art of Nazi era. Like all authoritarian art, it is realised in bad taste. But kitsch certainly has its own power.

Jan Manski, Supremant 2014, oil on canvas 154.5 x 107 cm, photo by Tom Horak

MW: Witkacy had predicted the upcoming war. Do you have any premonition of the future development of art and art activities?

JM: It’s very encouraging that there is no single tendency in art. After ages of dependence art is finally free and I hope it will stay this way. Various approaches and a broad range of ideas coexist – this is a very healthy condition. I think new technologies will change art as well as our future society. I expect that holograms and new kinds of 3D experiences will come from cinema to art. But still the classical techniques like oil on canvas will remain in position.

Jan Manski, Implement VII, 2013, 33 x 70 x 38 cm (13 x 27 1/2 x 15 in)

found tools and measuring instruments, shelf,

horse skull, polyvinyl acetate, soil, fur, photo courtesy of artist

Edited by Contemporary Lynx