2020 has been a tough year so far and as museums and art galleries began to reopen all over the world, The Arsenal Gallery in Bialystok is soon to open its latest exhibition, “Fear”. The exhibition will be on view from the 21st of August until the 18th of October and will analyse the “culture of fear”. Why is fear so omnipresent in the current public debates? Is it political? Is it culturally and historically contingent? Contemporary Lynx spoke to the exhibition’s curators – Monika Szewczyk and Eliza Urwanowicz-Rojecka on one of the most interesting phenomena of our times.

Installation view, exhibition „Fear” Arsenal Gallery power station, Bialystok , photo Maciej Zaniewski

Maria Markiewicz: The aim of the “Fear” exhibition is to analyse the “culture of fear” phenomenon. What does this expression really mean? How will it be approached at the exhibition and how should we understand it?

Monika Szewczyk, Eliza Urwanowicz-Rojecka: This term depicts one of the possible perspectives that can be adopted while thinking about fear, namely the socio-cultural context. Simply speaking, fear became a pivotal category in public life. The omnipresent and increased feeling of danger and uncertainty influences not only the way we function in everyday life, but also the nature of interpersonal relations. Apart from that, the “rhetoric of fear” is understood literally and has already established its position in our everyday language.

One of the creators of the term “culture of fear” is a British sociologist Frank Furedi. This issue was also a subject of interest for Barry Glassner. Frank Furedi emphasized that anxiety, as a construct derived from culture, is often exaggerated, while Barry Glassner claims that the highlighted problems are not necessarily those which pose a real threat.

Fear is understood as an idea evolved over the centuries. Its structure and meaning is shaped partly by the systems of meanings and values, which are subject to transformation and subsequently influence the way we behave. This origin and meaning of various forms of fear, as well as the ways they are established seem the most interesting. This is the area of our interest, however we do not claim that the exhibition will be a “laboratory of contemporary culture of fear”. It will rather be a “litmus paper” which will indicate or reveal certain aspects of fear.

Installation view, exhibition „Fear” Arsenal Gallery power station, Bialystok, photo Maciej Zaniewski

MM: Fear is sometimes claimed to be something positive which motivates us to make an effort and act effectively. Is the fear which is the topic of the exhibition the negative one, the one which cripples our efforts and incapacitates us?

MS, EU-W: It seems to us that, more often than not, fear is not a motivating force these days… The excreted adrenaline motivates us, but the fear itself… At first we need to tame it, get accustomed and deal with other negative emotions which often come along with fear. In order to do that, we have to call it by its name or diagnose it. This is what our exhibition can help everybody with. We do not assert that it presents the broad systematics of the phenomenon in question. Nevertheless, it definitely shows various points of view and different ways in which fear is experienced.

Fear is not only a consequence of traumatic situations, but it can also be felt when someone is helpless. We, for example, admit to feeling anxious due to the awareness that we are not able to present the topic exhaustively! The majority of presented works is neither “paralyzing” nor “overpowering”. They rather present our everyday fear and its escalation, or make the audience aware that the phenomenon of fear follows certain events from the recent or distant past and is ultimately universal.

We also present works which show the moment when people try to overcome their fear and turn it into their strength, for example the video work entitled “To be or not to be” by Anna Daučíková. What we also show are attempts to go through fear, to discuss it extensively in order to be able to act later on and stand up to what caused this feeling or to regain the feeling of power (work by Paweł Żukowski). There are also methodical analyses by Marina Naprushkina based on her long-lasting work with refugees.

Installation view, exhibition „Fear” Arsenal Gallery power station, Bialystok, photo Maciej Zaniewski

MM: What are we afraid of? Cataclysms, pandemic, otherness?

MS, EU-W: Currently? We are probably afraid of everything. Or maybe every single one of us has their own triggers of fear. The pandemic of fear expands thanks to various actors in our social and political life. On the one hand, we are aware that we are being manipulated. On the other hand, there is an increasingly strong feeling of being powerless, having no control over our own lives, being abandoned in the face of crucial decisions and lacking the tools to overcome the fear itself.

“It is fear that I am most afraid of” said Michel de Montaigne. We are afraid of our fear, emotions which come alongside and what they will prompt us to do. Maybe the time has come to deeply analyze this phenomenon.

Installation view, exhibition „Fear” Arsenal Gallery power station, Bialystok, photo Maciej Zaniewski

MM: Nowadays politics most often produces collective fears, because it is much easier to govern a society which is scared. Are the Poles a scared nation?

MS, EU-W: It is not only in Poland that fear management became a powerful tool. Unfortunately, it seems a very universal one. Indeed, we can say that the Poles are anation with a “siege mentality”. “Fighting” is what we are good at and it is easy to convince us that danger is everywhere around us and persuade us to remain mobilized. The most alarming things are very strong stereotypes and prejudices which lead to nationalism and trigger aggression against “others”.

Therefore, we need to emphasize that works by Ukrainians, Byelorussians and Georgians are also presented at our exhibition. It turns out that certain experiences from history are common to us all, but sometimes we deal with them in a different way and reflect on them distinctively.

12. A.R.Ch (Mikhail Syenkov), From the “Black Icons” and “Canine Wedding” series, 2004-2005, whatman,mixed technique: pencil, watercolour, wounds, blood, photo Maciej Zaniewski

Due to the fact that the artist’s works were stopped at the border by the Belarusian customs services, we show one of the twelve planned works by the artist.

MM: Fear is what stems from history and is an element of culture. Will the fear presented at the exhibition be shown from the perspective of the post-Communist states?

MS, EU-W: This was rather hard to avoid because artists from the East very often elaborate on contemporary history and constantly analyze it. It is much different in Poland where reviewing the communist past does not matter so much anymore in the face of new, urgent problems. Nikita Kadan, Sergey Shabohin and Yevgenia Belorusets are artists who work around the topic of the politics of memory and collective memory. They conduct extensive research on the influence of the communist past on a capitalist society. It seems to us that this in-depth analysis allows them to see more.

The atrocities of the Stalinist era in Georgia cast a shadow over neat photographs by Guram Tsibakhashvili. In the case of Vlada Ralko, her interest in history and archives is more subtle. This, however, does not mean that her hybrid figures delicately express her deeply-rooted inspiration in the reality of the USSR and its strangling system.

Sergey Shabohin, Pyramid of Alienation, 2020, neon, glossary, photo Maciej Zaniewski

MM: It seems to me that the exhibition about fear harmonizes with this year’s events. The year started with tragic bushfires in Australia and the catastrophic visions of World War III. As it went on, the global coronavirus pandemic unfolded. How much do the current events have in common with the exhibition?

MS, EU-W: When we invited Natuka Vatsadze, Nikita Kadan and Sergey Shabohin to cooperate with us as curators of this exhibition, which was roughly a year ago, it seemed to us that the project will be partly about the end of the world as we knew it and partly about the atmosphere related to this change, fear, manipulation and being lost due to information overload. We talked about what predominated the reality as we saw it, so, in other words, we talked about fear. Maybe we should have talked about embarrassment or madness, but what we felt was fear. Since that moment more and more reasons have emerged that supported our decision to take on this topic. Works by some artists presented at the exhibition may have a lot in common with climate change (for example works by Agnieszka Polska, Tamar Nadiradze and Kote Jincharadze). There are also works on display which depict the experiences related to the current pandemic, for example “Face masks” by Rafał Bujnowski made by wiping the dirty brush in pieces of paper towel, or a sound work by Hubert Czerepok which combines the “Stay at home” catchphrase with the artist’s guidelines on the necessity to read books to overcome the danger of the upcoming “pandemic of illiteracy”. In our opinion, the predominating motive is a certain universal depiction of fear filtered through the sensitivity and experiences of an individual.

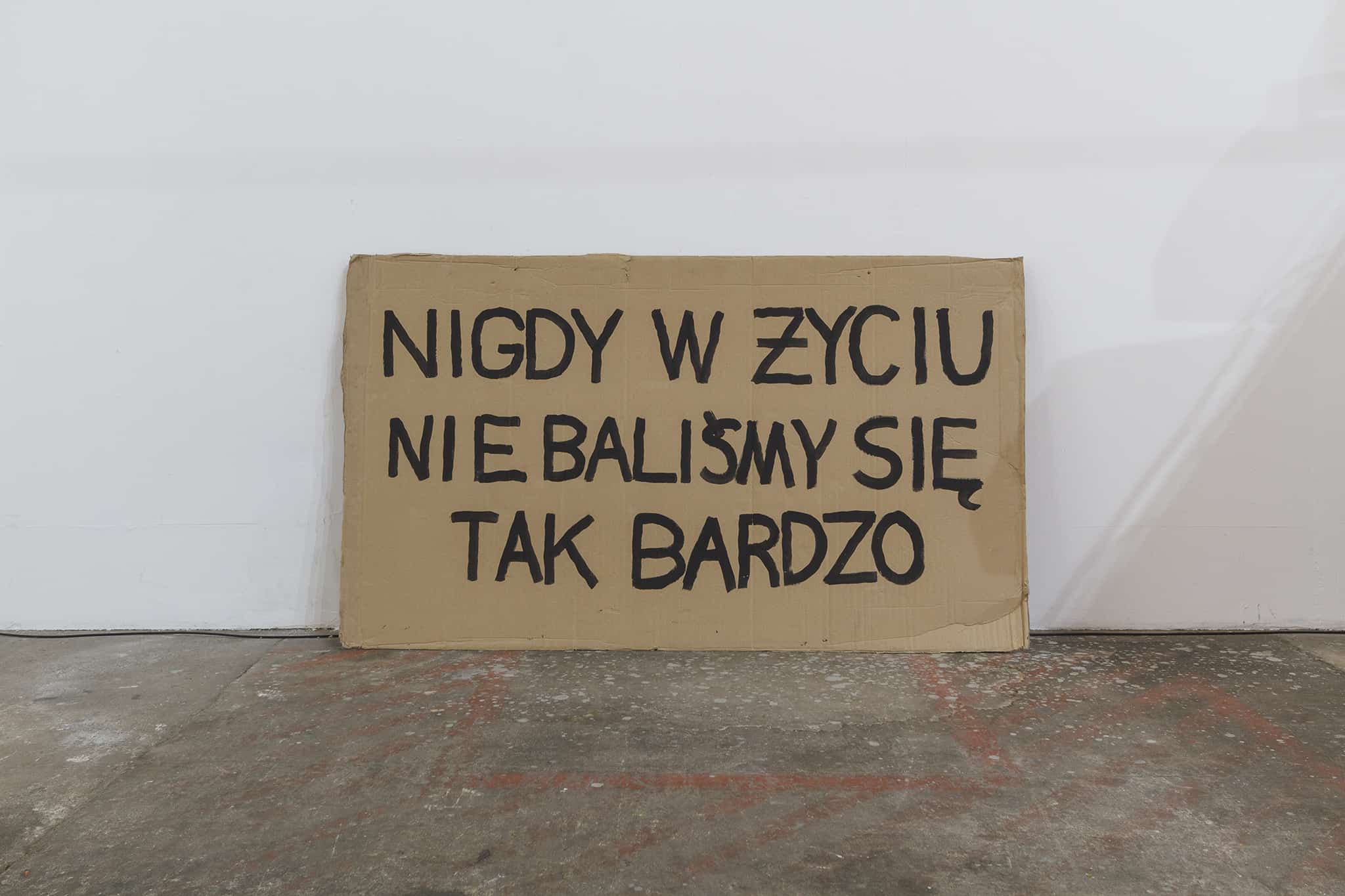

Paweł Żukowski, Never Have We Been This Frightened, from the ‘Cartons’ cycle, 2019, acryl on recycled cardboard, 147 cm x 85 cm, photo Maciej Zaniewski

MM: Psychology seems to confirm our beliefs that various phobias that we have stem from our childhood. However, the fear which accompanies us every step of the way does not seem to be the result of our personal experiences. Is it then stirred up by mass media and politicians?

MS, EU-W: Subjective fear is an extremely interesting, separate topic. It is sometimes claimed that fear is one of the first emotions we experience. It is, however, more atavistic when approached from this perspective.

When we take the social and political context into account, indeed it seems that the political players are the strongest forces which manage and sometimes manipulate fear in order to achieve certain goals or support certain views. This category is also used to gain control over society and politics. Mass media use viral mechanisms in order to escalate fear. They often use fear as the element of their aesthetics as well. Nevertheless, the media are most probably merely, or just as much, the carriers of a specific narration which is a part of a broader cultural context.

It has to be noted that there are many such actors and carriers of fear-related narration. Collective fear is not only produced by politicians. There are many more ideological contexts which consolidate fear and more actors in the society who intentionally generate it. There is even an excellent expression, namely fearmongers or “sowers of fear”. It is them who are responsible for “the management of fear”.

Alesia Zhitkevich, There are beaches where it is difficult to hear voices due to silence, 2019-2020, two-channel sound installation, C-print, armchair, photo Maciej Zaniewski

MM: Popular culture is full of apocalyptic visions and images of danger caused by humans and nature. Threats emerge virtually from every corner. Will the exhibition explain to the audience how they can defend themselves against fear and answer the question of whether their fears are justified?

MS, EU-W: Art does not provide us with ready-made answers. It sometimes helps us to intently listen to selected issues or to communicate them. Also, it gives us an impulse to reflect. The aim of this exhibition is not to develop specific tools which will defend us against fear. It however gives us a stimulus to think about the existing opportunities, it is an attempt to stimulate emotions which would counter aggression and helplessness. It is also an impulse that maybe will make us feel more powerful. Male and female artists help us see the problem and call it by its name. This is the way to get accustomed to fear and to deal with it.

Rafał Bujnowski, Masks, 2020, 11 drawings, oil on paper, each 23 cm x 26 cm, photo Maciej Zaniewski