This year marks the 243rd anniversary of the Declaration of Independence that severed the economic and political ties of the North America states from the British colonies. In order to commemorate this extraordinary day and the greatest symbol of freedom in the eyes of its citizens, we take a closer look at American art, especially paintings that achieved iconic status owing to their depictions representing the milestones in the US history. The following paintings are the genuine epitomes of artistic freedom.

Return to origins of the American painting seems necessary if one were to thoroughly understand its long transformations and ultimate richness. Although the US tradition did, in fact, emerge from the artistic vacuum, today it is New York that holds an undeniable allure to most Europeans. Once upon a time, the citizens of the New World were the ones who travelled to Europe to receive art education and familiarise themselves with dominating tendencies.

Ammi Phillips, Girl in Red Dress with Cat and Dog, c. 1835The American Folk Art Museum, New York

Ammi Phillips, Girl in Red Dress with Cat and Dog, c. 1835

The American Folk Art Museum, New York

The self-taught artists were denied the presence of former masters whose style they could’ve emulated. They were the so-called limners who created flawed portrayals of schematic background detail, clothing and facial expression. The pieces from the early Colonial period offer an utterly fascinating insight into the evolution of the spiritual and material culture in America. Some of their attributes manifest themselves even in contemporary American painting. Image composition was then based upon large expanses of colour, frontality, linearism and flat surface. No attempts were made to create an illusion of depth. The style itself was rather decorative. Artists of the period strived to paint the most realistic portraits possible. Hence the American painting will forever be entangled in a relation between realism and abstraction.

Native and simplistic portrayal was soon to be superseded by other forms of representation illustrated by some of the iconic paintings discussed in this article.

THE UNBREAKABLE AMERICAN SPIRIT

Grant Wood, American Gothic, 1930The Art Institute of Chicago

Grant Wood, American Gothic, 1930

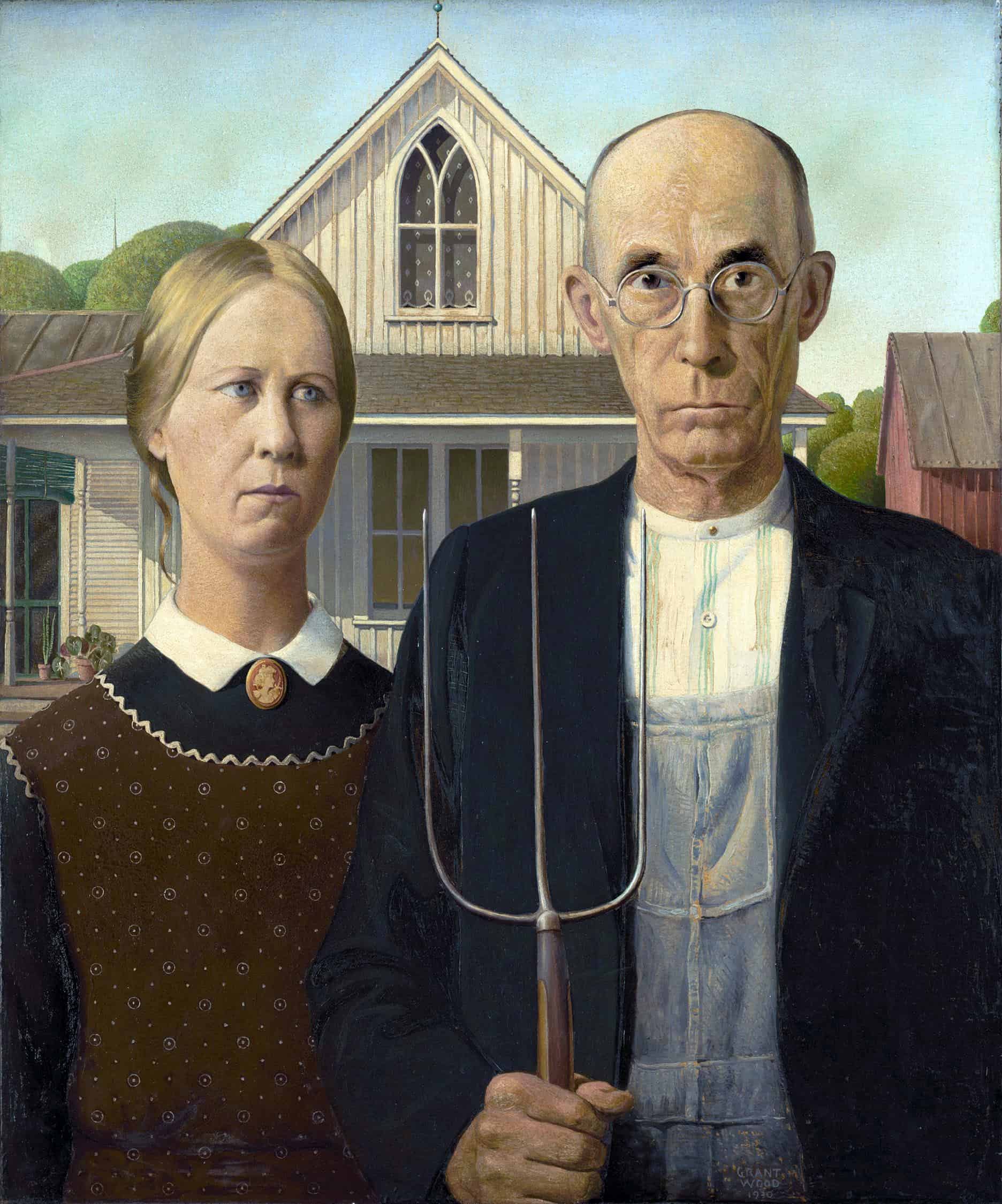

One of the most famous paintings, which earned its place in the popular culture, is American Gothic by Grant Wood. The piece was parodied for the first time by Gordon Parks in 1942 – it was the photograph featuring a cleaning lady against the backdrop of the US flag. A freewheeling play on the original image commenced. American Gothic was granted a brand-new life on the internet.

Representation was then meant to convey metaphorically the perseverance and resilience of ordinary citizens. American Gothic seems unremarkable and uninspired – and therein lies its strength.

The painting, which was completed in three months, depicts an older gentleman and a younger woman standing in front of a white house built in the carpenter’s gothic style of architecture.

Wood entered the painting in a competition at the Art Institute of Chicago. The third prize for American Gothic took him by surprise. Ever since then the painting has lived the life of its own. Not only did the image itself enter the cultural canon, but the captured building was also appreciated. In 1972, the house was listed on the National Register of Historic Places.

SOLITUDE / ISOLATION – THE AFTERMATH OF WAR

Edward Hopper, Nighthawks, 1942The Art Institute of Chicago

Edward Hopper, Nighthawks, 1942

One of the most recognizable 20th-century paintings in America, as well as worldwide, portrays four remote figures evoking a sense of loneliness. While looking at Hopper’s Nighthawks, a spectator feels entirely alienated from the scene in a diner. Although the artist himself claims to have been inspired by an actual locale in the New York City, the image carries universal connotations. Its timeless quality represents a critique of the modern world with no place for human connection. Hopper alludes to the events in the early 1940s, when the United States was embroiled in the II World War by the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor. It was the first time in history that the American people could feel threatened.

FREEDOM AND GRATITUDE

Norman Rockwell, Freedom From Want, 1943, Norman Rockwell Museum

Norman Rockwell, Freedom From Want, 1943

Rockwell’s painting is a direct reference to the celebration of Thanksgiving in America. The image depicts a traditional family dinner attended on this day by most citizens. The festivities might’ve looked differently in the past, however.

Freedom from Want was first unveiled to a wider audience in March 1943 – as an illustration to the article published in Saturday Evening Post a good couple of months before Thanksgiving.

The piece belongs to a series of four paintings entitled Four Freedoms that were inspired by the 1941 State of the Union Address delivered by President Franklin D. Roosevelt in which he listed fundamental values in peril.

“The third is freedom from want – which, translated into world terms, means economic understandings which will secure to every nation a healthy peacetime life for its inhabitants-everywhere in the world” – President Franklin D. Roosevelt, 1941.

The repercussions of the Great Depression (1929) and the US engagement in the I World War were still etched in citizens’ memory as the president articulated these words. In this moment, they realised that the world could be poles apart from the scene in Rockwell’s painting.

CONSUMERISM – MAN AS A PRODUCT

James Rosenquist, President-Elect, 1960

The popular belief tends to reduce the history of President John F. Kennedy to his assassination in Dallas, 1963. However, the cult figure of JFK went down in the history of America after amateur pictures from the shooting taken by a random first-hand witness were published in LIFE magazine.

Even before these events, John F. Kennedy stirred up strong emotions among the American electorate, which placed their fervent hopes in the candidate. It seemed as if the likeness of the future president had been elevated into a product and symbol of political aspirations.

James Rosenquist, an artist and former billboard painter, succeeded in capturing this specific feeling. His compositions were inspired by large-scale modern advertising and the tradition of surrealist collage. In this case, the artist presents a juxtaposition of Kennedy’s smiling face with a slice of cake and a car representing the culture of consumerism. The face itself was sourced from the president’s own campaign poster. Did Kennedy’s big promise boil down in fact to a Chevy and a piece of cake?

HOPE VS. CHANGE

Shepard Fairey, Barack Obama poster „Hope”, 2008

Kennedy’s campaign poster is not the only political image that went down in history. The cult status was also achieved by Barack Obama due to Shepard Fairey’s now iconic yet largely coincidental piece.

The street artist’s intention was to create a portrait that would evoke a direct human connection and positive emotions. Simplicity of execution conveyed a clear easily absorbed message that resonated with a large number of people. His work was influenced by Andy Warhol. The artist himself cites constructivism and social realism as his main sources of inspiration.

A widespread perception of Obama as a visionary was underscored by Fairey’s piece, which demonstrated the potency of influential graphic design and art. Similarly to the limners, he based his expression on colour and austerity of form.

Bibliography:

1. American Painting, ed. Francesca Castria Marchetti [translated from Italian into Polish by Hanna Borkowska, ed. Małgorzata Jendryczko], Warsaw 2005.

2. American Painting: From Its Beginnings to the Armory Show, with an introduction by John Walker, ed. Jules David Prown [translated into Polish by Halina Andrzejewska], Warsaw 1994.

3. American Painting: The Twentieth Century, Barbara Rose, Warsaw, 1991.