2020 IN ART:

THE YEAR OF TRANSFORMATIONS

teamLab, The Infinitive Crystal Universe, 2018, Interactive Installation of Light Sculpture, LED, Endless, Sound: teamLab, Copyright teamLab, Courtesy Pace Gallery

What happened in 2020? None of the emblematic ritzy art fairs, glitzy openings, crowded blockbusters, and ostentatious auctions that the art world used to know so well. They belong to the dim and distant past now. Although the art world is an event-driven industry, 2020 was all about triggering transformative processes rather than participating in memorable affairs.

As the pandemic raged on, the decline of face-to-face interactions and global mobility, synonymous with the art world operations, placed a significant strain on each corner of the community. This unprecedented time shook up the industry, pushing many players to explore innovative approaches and test next-generation operating models in an effort to ramp up business. With multiple transformations occurring across the board, we’re going to talk in terms of before and after 2020 in art.

Matthew Burrows MBE, Founder and Director of Artist Support Pledge, Copyright Matthew

Burrows

The power of virtual connection

The art world’s long-lasting way of operating in a stubbornly analogue manner come as no surprise. After all, experiencing art is a multi-sensory adventure and experiences of co-presence with auratic artworks are critical. Audiences need a sense of immediacy and personal connection to something tangible. 2020, however, ended that status quo. Zoom and Instagram, some of the most egalitarian media platforms, revolutionise day-to-day lives of all art world actors. Although it is about the mighty power of the Internet in general, Zoom and Instagram in particular galvanised attention this year.

Since most of the spaces where we experience art were abruptly out of bounds, even the most hesitant mediators amped up their online outreach. While in 2019 a virtual studio visit was considered as a last resort, in 2020 a studio visit via zoom didn’t raise eyebrows at all. Even though virtual meetings seem a poor substitute for face-to-face communication so central to reinforcing trusting bonds, they do allow for participating in socialising and art business activities to some degree. We entered a new era where it is not your geographical location that gives you access to first-class events and compelling offers, but your broadband width.

With the help of Instagram numerous artists were able to make ends meet this year too. The Artist Support Pledge, set up in March by Matthew Burrows, is an artist-led movement and network aimed at supporting creatives struggling financially during Covid-19. The concept is straightforward: artists sell work for £200 or less thought the scheme by posting images of the works on Instagram with the hashtag #ArtistSupportPledge, with the pledge that once they sell £1,000 worth of work, they buy a piece by another artist. This unprecedented economic model attracted thousands of buyers and revealed a new “gifted and egalitarian micro-economy” that has generated on average £15m a month since March 2020. Built on generosity and inclusivity, the Artist Support Pledge quickly became a global movement and Matthew Burrows was awarded an MBE (Member of the Order of the British Empire) in recognition of his service to the arts in the Covid-19 response.

Tate Modern, Exterior View, Photo Rikard Osterlund, Courtesy Tate

Job cuts

In spite of governments across the globe unlocking generous aid packages to help the cultural sector, the calamitous impact of the pandemic didn’t allow art and cultural organisations to save enough. To respond to the toughest challenge of a generation and survive the crisis, the art and cultural institutions decided to reduce their workforce.

Projecting millions of dollars in losses, Whitney Museum laid off 76 staffers in early April, and MoMA’s staff of 960 employees was reduced to about 800 workers. “We will learn to be a much smaller institution,” MoMA director Glenn Lowry reportedly said on a video conference call with other museum professionals in May 2020. Tate, Southbank Centre, Victoria and Albert Museum, Science Museum Group, and many other big galleries and museums hit hard by the pandemic announced that they would be consulting staff on job cuts. After 295 redundancies across Tate Enterprise in 2020, Tate plans to reduce its workforce by further 12% in all departments and at all levels (equivalent to around 120 full-time roles) in 2021.

This unwelcome process shows that operating models of major art and cultural institutions closely resemble those employed by tourist attractions and business-oriented enterprises. Suddenly, all the fanfare about positioning big museums as art sanctuaries looks like a mere publicity spin. “With tourism not expected to return to previous levels until 2024/25, and the wider economy facing the long-term effects of the pandemic,” Maria Balshaw, Tate’s Director, and Vicky Cheetham, Tate’s Chief Operating Officer, warned, “the road to recovery will be a long one.”

Philip Guston, The Studio, 1969, oil on canvas, 180 x 186 cm, Copyright the estate of Philip Guston

Systematic scrutiny

Over the last couple of years, the public has begun to take a closer look at how big art institutions – public museums in particular – spend their money and what the sources of their income are. With so many underpaid art workers voicing their disapproval, it comes as no surprise that the public’s watchful eye has been kept on the way art organisations are run.

2020 saw many institutions focus on crisis management. On the one hand, they had to address the pandemic and the subsequent loss of income. On the other, organisations had to deal with the staff’s resentment of the money at the top of the pipeline and complaints about how donors generate their revenue. The ongoing redundancies didn’t help to bury the hatchet either. In the last couple of years, The Whitney, the Museum of Modern Art, the Louvre, and Tate, faced scandals regarding the sources of their trustees’ financial resources. The protests concerned Warren Kanders (defence contracting), Larry Fink (investments in private prisons), the Sackler family (opioids), respectively. To avoid more public outcries, numerous museums began to implement new guidelines and more thoughtful processes for accepting certain funds.

While the commitment to differentiate between clean and dirty money was eagerly welcomed by the public, some exhibitions drew ire because of their polarising content, namely Philip Guston Now. The Canadian American painter rose to fame in the 1960s and 1970s for paining representationally in a personal, yet cartoonish manner. He would often include images of Ku Klux Klan figures, social unrest, racial conflict, and even invocations of the Holocaust in his works. After tumult, the travelling show – sponsored by four renowned institutions: Tate Modern, the National Gallery of Art in Washington, the Museum of Fine Arts in Houston, and the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston – was postponed until 2024. In a joint statement, the museum directors declared: “The racial justice movement that started in the U.S. and radiated to countries around the world, in addition to challenges of a global health crisis, have led us to pause.”

The delay of Philip Guston’s retrospective divided the art world. A Tate curator was suspended for condemning the move, and over 2,600 artists, writers, curators, and critics signed an open letter strongly criticising the museums’ lack of courage to display the work, attempt to interpret it, and engage in reckoning with history, including the institutions’ own histories of prejudice.

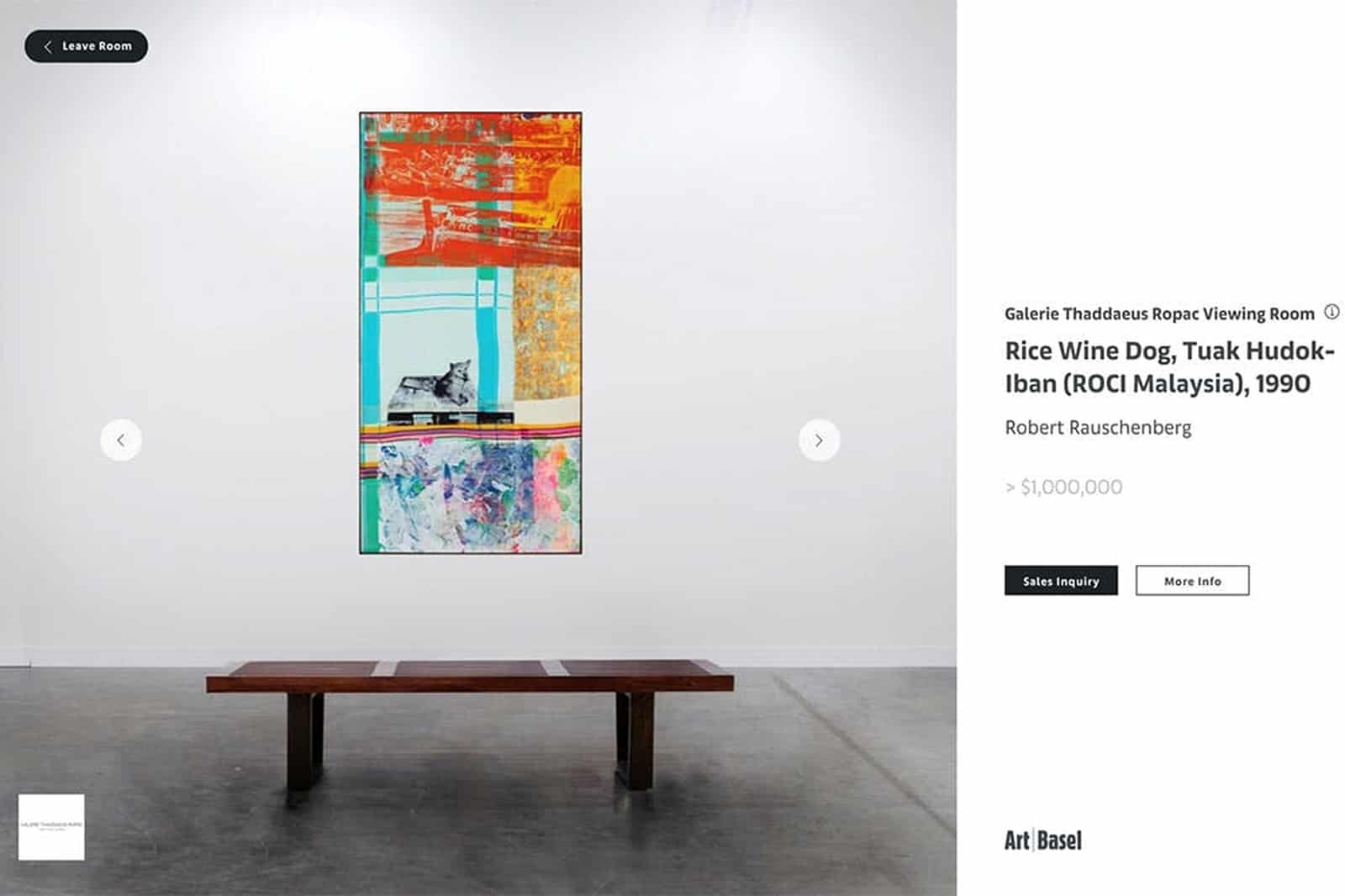

Screenshot of Galerie Thaddaeus Ropac’s online viewing room at Art Basel Hong, March 2020. Courtesy Art Basel Hong Kong

Embracing the digital

Can you imagine that Hauser & Wirth, one of the largest art players in the world, had never held an online show until March 2020? This year’s adverse environment questioned outdated ideas about selling art digitally and forced a complete rethink of the stubbornly analogue art world. Both major and small galleries and organisations took big swings at online innovations and channelled their efforts into reshaping the narrative of digitally enabled spaces.

The first major art fair to launch solely online was Art Basel Hong Kong in March. Online Viewing Rooms connected the world’s leading galleries with a global network of collectors and art enthusiasts. As the severity of the pandemic became clear, the initially postponed summer edition of the original Swiss fair was also replaced by its digital substitute. Same happened to Frieze London, TEFAF, Art Basel Miami, and many others. No matter how sceptical art dealers sounded in the beginning, robust sales of high-value works were reported at all the fairs.

Businesses were brisk outside the fair ecosystem too. While certain functions – for example, those in shipping departments – are not a full-time jobs anymore, the art world has seen a surge in demand for digital specialists. After initial downsizing of their workforce, Sotheby’s and Christie’s hired many new talents for their digital teams. So did galleries and other cultural institutions kicking off new digital offers. In early April, David Zwirner announced Platform, an online viewing room featuring smaller galleries. It allowed invited friends, peers, and colleagues from galleries around the world to digitally present a focused presentation of works by a single artist. Gagosian Gallery opted for time-limited virtual shows of one artist a week, with one work on offer for just 48 hours. With dozens of other online initiatives also gathering momentum, the dynamics of transitioning online and interacting digitally at a distance evolved rapidly in 2020.

Hauser & Wirth Los Angeles, Photo Joshua Targownik, Courtesy Hauser & Wirth

The strong get stronger

The processes of 2020 will have lasting impacts on fragile institutions. While everyone invests in their online capabilities, establishing and enhancing an online presence is often an expensive and exhausting task for small institutions or artists. The mega galleries, however, seemed to enter an arms race and have shown to signs of stopping.

The big players — namely Hauser & Wirth, David Zwirner, Gagosian, and Pace — rose to power in recent years and operate out of dozens of cities worldwide. While Gagosian boasts 18 exhibition spaces in 11 cities and Hauser & Wirth expanded its portfolio to 12 locations, Pace and David Zwirner seem to be rather modest with 8 and 6 exhibition spaces, respectively. Regardless of the number of showrooms, each of these art world players is a remarkable creative thinker and have come up with innovative strategies to reach even more clients. To keep up with ever-changing contemporary art landscape, Pace has recently launched Superblue, a groundbreaking enterprise dedicated to producing, presenting, and engaging the public with experiential and immersive art. David Zwirner, in turn, has conceived one of the most compelling and multi-layered online Viewing Rooms that industry has seen.

The mega galleries have sprouted into institutional behemoths, organising more and more museum-quality exhibitions. Their ambitious art programmes, which include monumental exhibitions, performances, lectures, film screenings, publishing projects, and panel discussions, have effectively reinforced their prominent position in the art world. These activities have also blurred the lines between commercial businesses and what a nonprofit with higher aims would typically offer to their audiences. Given the ease of access to a plethora of compelling offers, it has already become increasingly difficult to tell the difference between a museum and a mega gallery.

Sotheby’s Live Global Auction Event: Sotheby’s specialists taking phone and online bids from around the world, Courtesy Sotheby’s

Records and losses

To lessen the impact of the pandemic on their businesses, the auction powerhouses ramped up efforts to entice clients and 2020 saw them stage unprecedented online events. Sotheby’s Live Global Auction Event in June, a marathon of online hi-tech auctions, was conducted remotely by chairman and auctioneer Oliver Barker in London who took bids from Sotheby’s specialists on phone banks in New York, Hong Kong, London, as well as online bidders. The ongoing sales were live-streamed via seamless, real-time video. Ultimately totalling $363.2m, the event set the highest price for an artwork auctioned online — Jean-Michel Basquiat’s Untitled (Head) sold for $15.2m.

Christie’s, in turn, made history with ONE, a global live auction offering Impressionist and Modern, Post-War and Contemporary Art and Design. Using streaming technology, this four-hour extravaganza took place in consecutive sessions in Hong Kong, Paris, London and New York, setting auction records for several artists, and realised $420.9m, selling 94% by lot and 97% by value. More than 80,000 people tuned in to watch ‘the new theatre’ unfold, with 60,000 of those accessing the auction through social media in Asia.

The broader view isn’t all rosy though. According to the latest report published by Pi-eX, an art market analytics company, the top three auction houses—Sotheby’s, Christie’s, and Phillips—experienced a 79 per cent year-over-year drop in revenue during the second quarter of 2020. Whereas last year, the companies saw $4.4bn during the second quarter, in 2020 they brought in only $0.9bn during the same period. This dramatic decrease is much more significant than the one that followed the 2008 financial crisis. Moreover, reports show that the art market confidence dropped dramatically from 85 points (out of 100) in 2019 to 6.4 in 2020, which constitutes the lowest reading since the study began in 2005.

Seven Saints of St Pauls (Iconic Black Bristolians Project), Artist: Michele Curtis, Courtesy Arts Council England

Towards diversity and racial justice

The surge in anti-racism protests across the globe this year alongside a rising interest in women artists and artists of colour contributed to further acknowledging the lack of true representation reflecting the art world’s exceptional diversity. Artnet conducted research in 2018 which showed that works by African American artists accounted for a mere 1.2% of the global auction market, while works by female artists represented just 2% of the market. Representation is a delicate issue and cultural institutions have gradually been making big steps in the right direction when it comes to inclusion and diversity.

Appalled by the violent death of George Floyd and responding to the Black Lives Matter protests around the world, the arts sector bodies, including the Museum Association, called for a stand against racial injustice. “Although nearly all cultural spaces are formally open to everyone, in practice they may only be accessible to a select group who have the financial, social or cultural capital to feel at home in them,” Darren Henley, CEO of Arts Council England, admitted and signalled structural changes and new approaches that may hopefully lead to welcoming, supporting, and nurturing people from all backgrounds.

To ensure a range of voices are heard, museums across the globe have finally begun to address gaps in their collections and re-arranged some of their galleries in order to include artworks more accurately reflecting the art world’s diversity and global art history. Artists of colour, female artists, and LGBTQ artists have made real breakthroughs at auctions. Several public bodies linked culture recovery funds with a pledge to promote diversity and inclusiveness. There has been a surge of initiatives aimed to foster the careers of aspiring black and minority creatives in a variety of ways too. While there is still a long way to go and plenty of challenges ahead, it is clear that it is not a market trend anymore but a new reality.

Will it be OK? Stefan Brüggemann in front of his public work ‘OK (Untitled Auction)’, commissioned by Hop Projects CT20, Folkestone, 2020, Photo Courtesy Hauser & Wirth

Future-proof metamorphoses

Crises accelerate disruptions of industry norms. 2020 not only altered society but also hastened transformations affecting the production, distribution, and consumption of culture. With so many technological advancements at our fingertips coinciding with the lack of physical interactions, we have entered a time of extremes.

While the recollections of crowded art spaces and collective effervescence are still vivid, the state of virtual solitude has become the nagging reality. Yet, hopes for a more diverse, inclusive, and accessible cultural industry seem more realistic than ever. Institutions, collectors, art collectives, and individuals plough their efforts into supporting emerging art and pushing the digital and immersive projects further. While we await the comeback of a jamboree of fairs, auctions, exhibition openings, galas, and parties, the art world has adapted to enter another decade of the 21st century with confidence and readiness for whatever the future brings.