6 ARTWORKS WE LOVED AT ART BASEL UNLIMITED

To create something without the limits: financial, special, technical it’s a dream of each artist. The dream is even bigger when the work which was created with a free spirit you sell in the first day of showing it (in the worst condition within one week) for a huge amount of money. Art Basel art fair makes this dream come true. This year 38 artists are shown during Unlimited. This section is curated by New York-based curator Gianni Jetzer. It’s a pioneering exhibition platform for massive sculpture and paintings, video projections, large-scale installations, and live performances.

We were there during the first, opening day and we choose 6 works which in our opinion were the most intriguing. Some of them were created by a younger generation of artists (Jacolby Satterwhite, Mika Rottenberg), well-known artists (Antony Gormley, Paul McCarthy, Monica Bonvicini), and some of them by classics of 20th-century art like Lucio Fontana, and Kaarel Kurismaa.

Jacolby Satterwhite – “Birds in Paradise”, 2019

Gallery: Mitchell-Innes & Nash

ideo/Film: HD video, objects, installation; 78’; edition of 5 + 2 AP

Birds in Paradise by Jacolby Satterwhite is a tripartite video installation comprised of a two-channel animation. The suite of films is scored by a conceptual folk recording the artist made from a cappella recordings written and sung by his late mother, the artist Patricia Satterwhite, and presented in a theater of objects that echoes the domestic space. Birds in Paradise – titled after a key record that speaks to the films’ visual refrain – is compiled from an archive of borrowed anecdotes, personal mythologies, drawings, and experimental-dance performance footage accumulated by the artist throughout his life. He derives his film-making strategies from Fluxus and Surrealist principles, revolving around chance and irrational juxtaposition for a queer Boschian tableau, punctuated by performances by artists, queer activists, dancers, sex workers, and actors from his community.

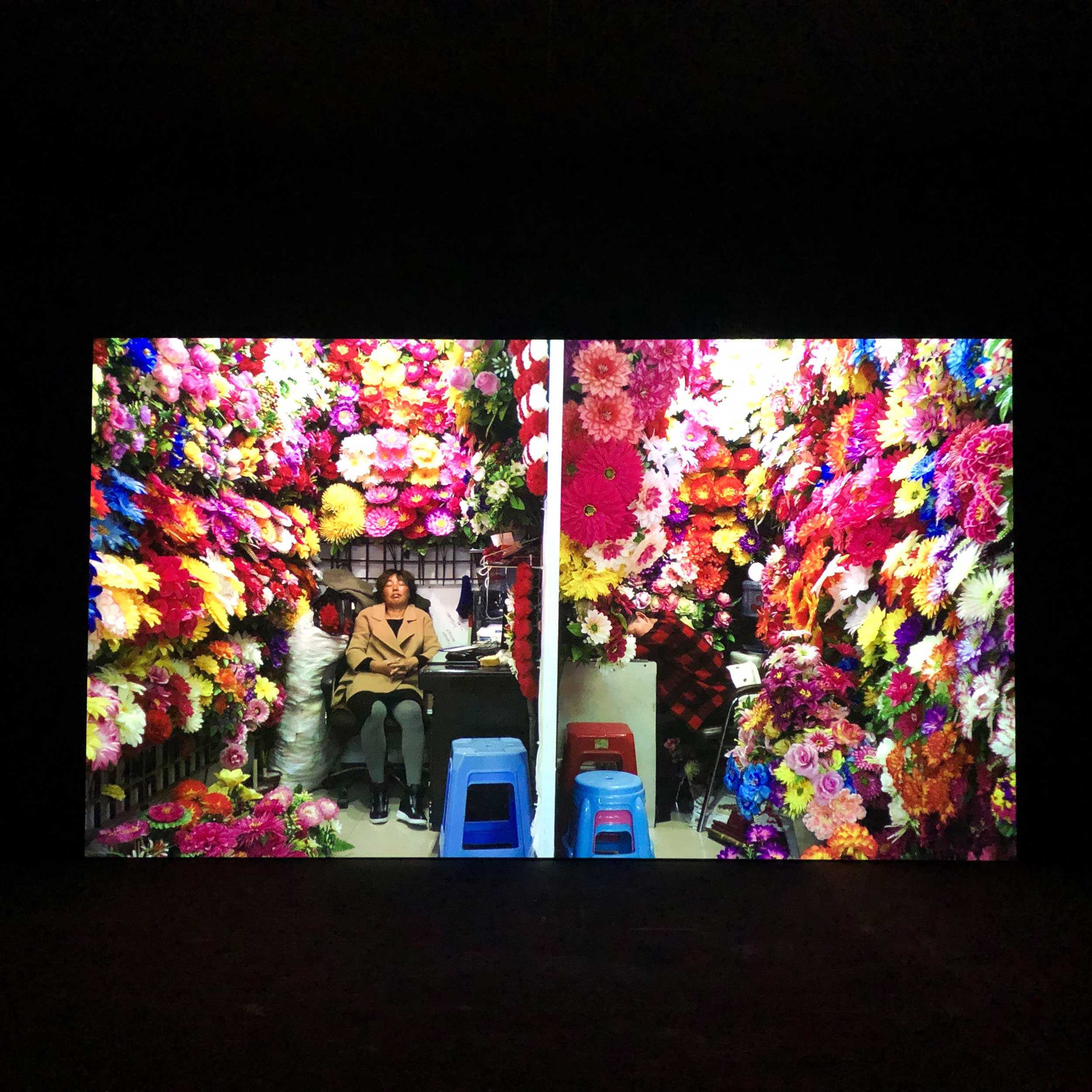

Mika Rottenberg, “Cosmic Generator (Loaded #3)”, 2017

Gallery: Hauser & Wirth

Video/Film: Sculpture and video installation; approx. 27’; dimensions variable; edition 6 of 6 + 1 artist’s variant

‘The thematic starting point for Mika Rottenberg’s work, “Cosmic Generator,” is a tunnel system that establishes a trading connection between various places and actors, among them the Mexican city of Mexicali and Calexico, the Californian town on the other side of the border fence. Rumor has it that the entrance to the system can be accessed via shops and restaurants in La Chinesca, Mexicali’s Chinatown. In her montage Rottenberg links footage from the local Golden Dragon Restaurant with a 99 Cents Store in Calexico and an enormous plastic commodities market in Yiwu, China. The Yiwu Market plays a pivotal role in this imaginary network peopled by a group of rather strange characters. With its artificial blaze of colors it seems like a gigantic staged performance in itself.’ – Excerpt from Andreas Prinzing’s text on Cosmic Generator at Skulptur Projekte Münster, where the work was first shown in 2017. Rottenberg has a solo show opening at the New Museum in New York in late June 2019, featuring a new work titled Spaghetti Blockchain.

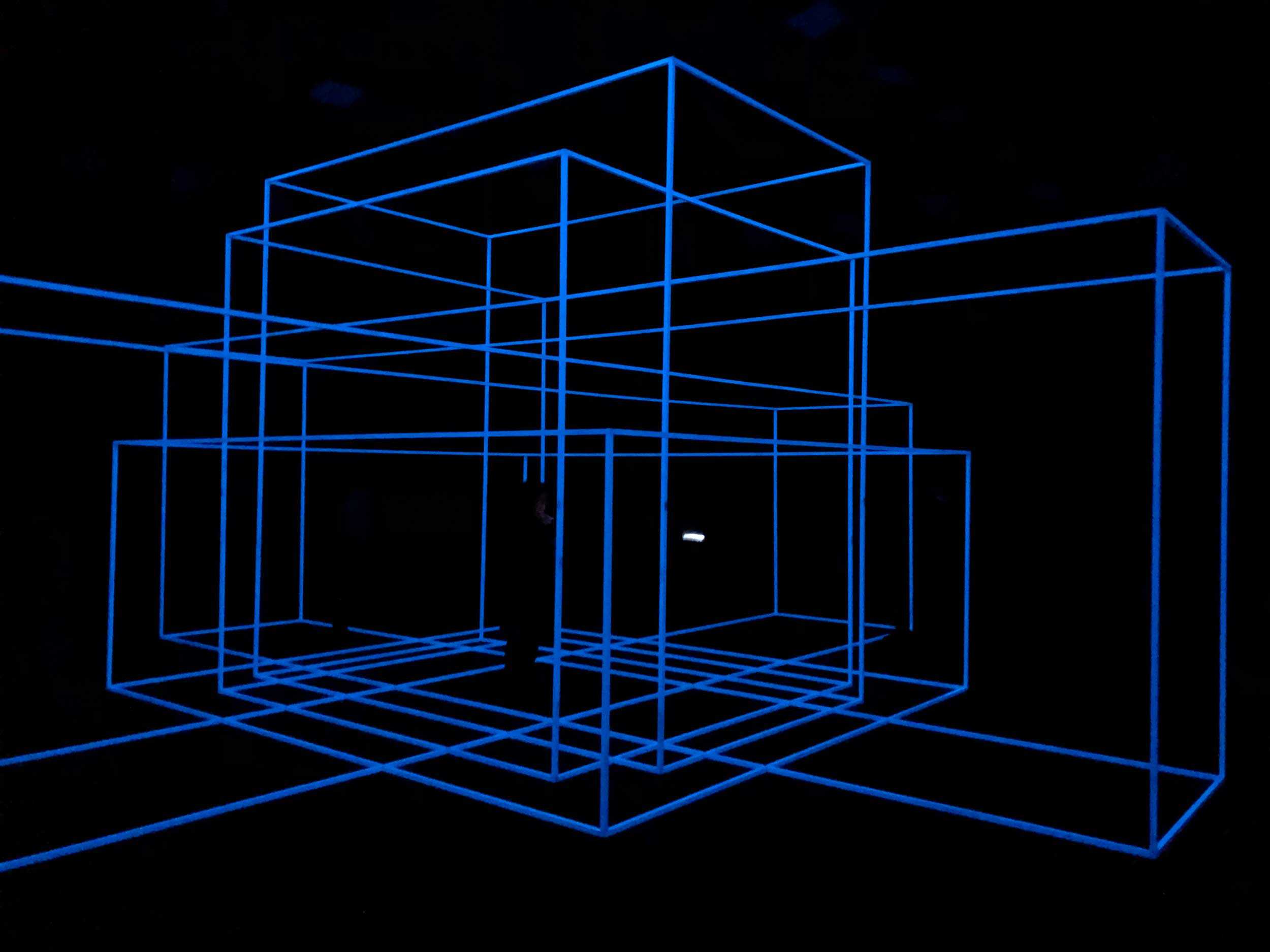

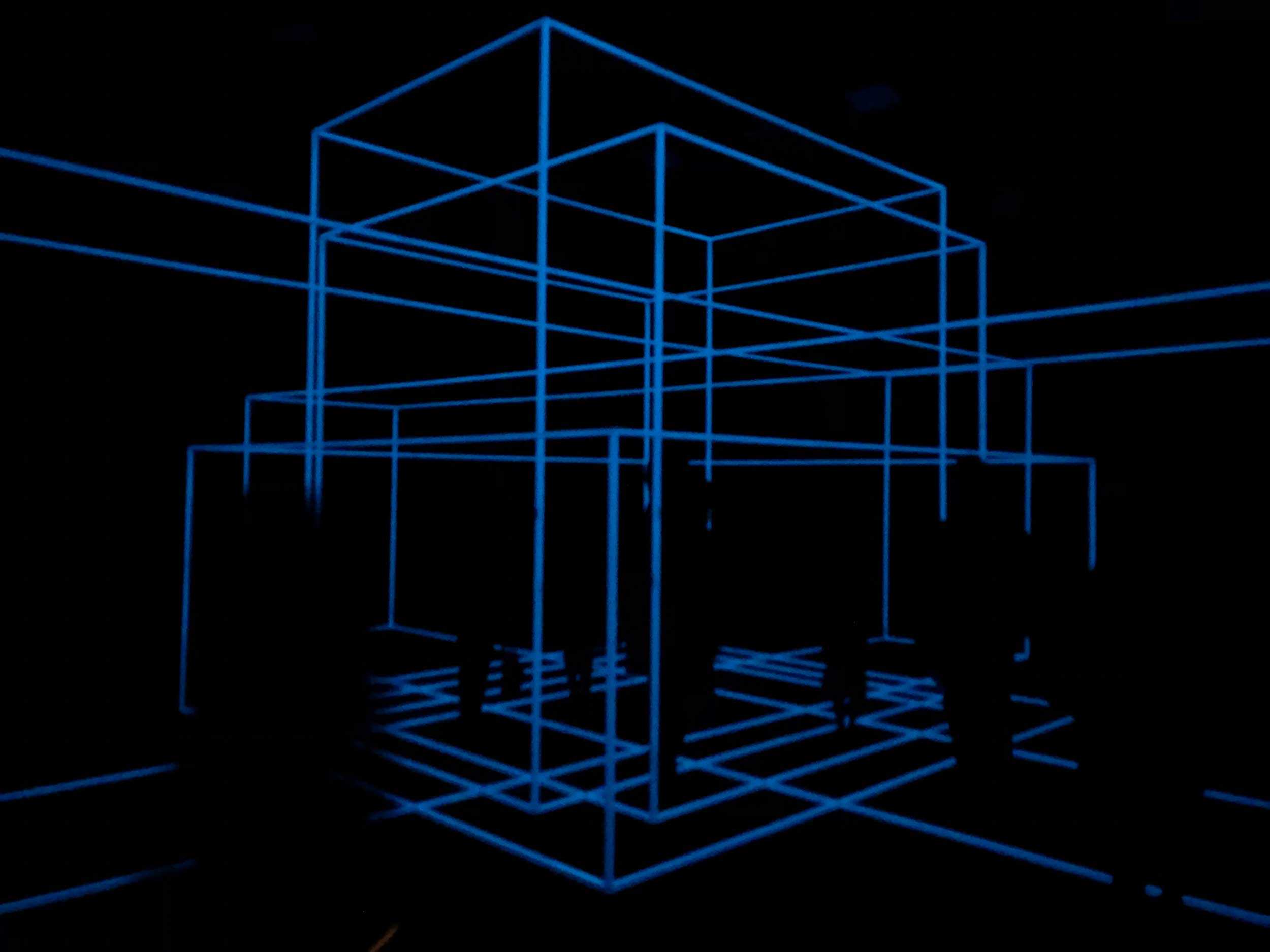

Antony Gormley, “BREATHING ROOM II”, 2010

Gallery: Galleria Continua

Aluminium tube, 25 x 25 mm, Phosphor H15, and plastic spigots; 386 x 857 x 928 cm

A hologram-like drawing appears in 10 minutes of darkness, followed by 40 seconds of intense light to reveal a space frame hovering between architecture and a drawing of architecture. Seven interconnected rooms of the same volume, but vastly different heights and lengths, rise from a mandala-like drawing on the floor. Here, the orthogonal structure of the built environment is compressed and extended, suggesting spaces within spaces that become a metaphor of the body and the site of its existence. The Cartesian determination of perspective, where the viewer is always in a privileged single point position, no longer applies. We are free to be inside or out of the frame. Ann Hindry, Curator of the Renault Art Collection, describes the experience as ‘being at the heart of a generous volume of air that seems to dilate like a big breathing body.’

Paul McCarthy, “Coach Stage Stage Coach VR experiment Mary and Eve”, 2017

Gallery: Hauser & Wirth, Xavier Hufkens

Video/Film: Virtual Reality, digital; between 5’ and 11’; Virtual Reality, director: Paul McCarthy; cast: Mary (Red) – Rachel Alig, Eve – Jennifer Daley; production: Alex Stevens, Naotaka Hiro, Jody Joyner; produced with Khora Contemporary

The work was created as 11 virtual reality experiments, using motion capture to transfer the real movements of the actresses into virtual reality. The virtual reality experiment is based on the long-term project of the artist, ‘Stagecoach,’ or ‘SC’ for short. Encompassing a wide range of different media, the project includes a new film, inspired by John Ford’s Western of the same title from 1939 starring John Wayne. Taking the form of a spin-off, a phenomenon associated with the entertainment industry, the VR work builds on a scene from the film of the artist, involving the two characters, Mary (played by Rachel Alig) and Eve (played by Jennifer Daley). Caught in the claustrophobia of constant surveillance by the two women and their doubles, the viewer becomes part of the vicious hallucination of a psychological mind game. Social conventions break down as the plot unfolds and escalates into a psychosexual trip of rape and humiliation.

Kaarel Kurismaa, “Steam Express and Halts”, 1993

Gallery: Temnikova & Kasela

Installation: Sculptural installation, mixed media; steam train: 70 x 400 x 300 cm, 2 halts: 120 x 60 x 60 cm each

Kaarel Kurismaa is best known for his pioneering work with kinetic and sound art in his homeland Estonia. Harmony between different means of expression make his works veritably enjoyable: flowing forms, contrasting colors, subdued sounds, pulsating or dimmed light, and movement are the common denominator. His pieces are soulful and theatrical, replete with human emotion. As in most of his objects, ‘Steam Express and Halts’ (1993) has been put together with readymade furniture and pieces from hardware stores, as well as objects he finds laying around: lamp shades, a hand washing device from a century ago, dolls and mannequins. The piece speaks to a childhood memory. The posts signify the two train stops where he used to watch the trains go by. The sign system used by the rail workers was puzzling to the little boy; and such movements, sounds and sign systems have found their way into adulthood, although not in a cold and analytical form, but in the exact form of that particular childhood memory. The angel on top of the train is covered by steamy clouds from time to time, and it becomes apparent that humor and light satire are never too far off on the horizon.

Monica Bonvicini, “Breathing”, 2017

Gallery: Galleria Raffaella Cortese, Galerie Peter Kilchmann, Mitchell-Innes & Nash

Installation: Steel structure, compressed air cylinder, compressor, rope, synthetic fiber, leather belts

For over 20 years, Monica Bonvicini has been creating sculptures and large-scale installations, drawings, videos, and photographs, to investigate the relationship between architecture and gender roles, sexuality and psychology, control and power. Her works question contemporary socio-political realities, the meaning of making art, and the ambiguity of language through a personal visual style and distinctive dry humor. A hanging sculpture made of leather belts moves through the space, loudly sweeping across and hitting the floor. The screeching and metallic noises of the belts crushing on the surface are accompanied by the industrial sound created by the pneumatic pistons that keep the installation in motion. The resulting movements are precisely programmed into a choreography reminiscent of a dance or a forced and repetitive mantra. Breathing is the title of the performative sculpture, frightening and meditative at once; the moving object, in the shape of a witch’s broom or an oversized whip, refers to contemporary feminist politics and the presence of powerful female figures.

Lucio Fontana, “Ambiente spaziale con tagli”, 1960

Gallery: Magazzino, Galleria Tega

White acrylic paint on plaster

Widely known as one of the most important artists of the 20th century, this presentation features the first known example of Lucio Fontana’s iconic slashed canvases transposed into an architectural element. The first ‘Ambiente spaziale’ was created in 1949. This series represents a pioneering example of installation and laid the foundations for his architectural-environmental kind of work. Fontana’s monumental ‘Ambiente spaziale con tagli’ (1960) is a resplendent example of the artist’s quest for an unknown dimension, a middle way between architecture and painting. Six dramatically rendered incisions perforate a thick white plaster, providing a tangible means for exploring the relationship between cosmic and material space. Originally executed as a ceiling for the house of Antonio Melandri, a well-known Milanese collector and property developer, this extraordinarily innovative work was followed by further ‘spatial environments’ created by Fontana for private residences and public spaces. These eventually culminated in Fontana’s renowned ‘white room,’ shown at the Italian Pavilion of the 1966 Venice Biennale.