In times of great uncertainty and the triumph of science, Alix Marie, Paris-born and London-based artist, talks to me about the similarities between art and science, image-making and working in a laboratory. We discussed her interest in Surrealism, how she approaches the body and space, and how she spends her time in lockdown, preparing for upcoming exhibitions.

Alix Marie

Maria Markiewicz: Your work merges photography and sculpture. Which of these mediums is closer to your heart?

Alix Marie: Both were there at the start of my interest in art and art-making as a teenager; I was taking clay modelling classes and staging my friends in photographs. When I went to art school, I couldn’t choose between photography and sculpture, so gradually the challenge became to mix both of them in the same pieces of work. Even if today sculpture and installation have taken a bigger place in my work, I think the photographic image will always be a part of it somehow.

Speaking more broadly, I think both of these mediums are connected anyway – the dissemination of sculptures in books or the internet happens through photography, and to show a photograph, you have to think about it physically, in terms of scale, presentation, and in relation to space.

MM: You often talk about the similarities between skin and photography, science, and art. How are these two fields intertwined in your practice?

AM: Of course, photography’s invention is rooted in science and is still very much part of its practice today. Photography plays a huge part in the practice of science, and science plays a part in the practice of photography. Whether it is the laboratory environment or computer-based image-making, the two will always be intertwined. But going beyond this, it is the experimentation with materials in the making of sculptures or images that draws me back to those parallels. Perhaps even more so because I work with the body and its representation. When I have to attach parts of moulds of a hand somehow, drive a tube through and move quickly, there is a childish feeling of playing surgeon. Most materials used in sculpting rely on chemistry, and for example what concrete is made of, the reactions between two components, the change of states in wax, are all part of my creative thinking while working. The material itself, its history, its capacity, what it is associated with are all aspects present in each piece of my work.

Sucer La Nuit, 2019, Musée des Beaux Arts Le Locle, © Samuel Zeller

Sucer La Nuit, 2019, Musée des Beaux Arts Le Locle, © Samuel Zeller

MM: Do you consider yourself a feminist? How is feminism manifested in your work?

AM: I think everyone deserves the same rights without regards to their gender, race, sex, or sexual orientation, and I believe we still live in a patriarchal world. That is me as a person and even if my political views are diluted in what I make, and that the construction of gender and its stereotypes is a subject present in my practice, I am unsure about describing my practice as feminist.

It seems to me that often practices described as such can be pigeonholed and read only as political when I think a work of art can be political, conceptual, poetic and so much more at the same time. This year, I was interviewed on the radio and on TV about my work but on both occasions, instead of my practice, I was asked about being a woman artist and the place of women in art. While I think those are important debates to be had, I know it would not have happened to a man if he did not come from a minority; he would have just talked about his work.

Alix Marie, 2014, Orlando, SHOW RCA

MM: Your works often tend towards the grotesque, surrealism, and camp. What inspires you as an artist? AM: It’s an odd timing to answer this, because yesterday, I have found a school assignment I did when I was about 15 on surrealism. An artist named Pierre Molinier, who I thought I discovered much more recently, was already in there. I think Surrealism is the art movement that has had the biggest impact on me and my interest in art.

Recently, I have been drawn to it again and found the women involved in the movement such as Justine Frank or Leonora Carrington. However, the biggest inspiration for my practice are myths; their stories, characters, influences and all my projects bare a reference to mythology.

Then, I think what has impacted me the most are films; if you mention grotesque, surrealism and camp in my work it will come as no surprise that my favourite films were made by Jean Cocteau, John Waters, David Cronenberg, Jacques Demy, Dario Argento, Vincente Minelli, Federico Fellini, and Alejandro Jodorowsky!

MM: In your bodybuilding series, you were interested in how masculinity is exhibited and performed in extremes. In “Orlando”, a large-scale installation made for your master’s degree, you are also exploring how gender is constructed and constituted, referring to Virginia Woolf’s novel that blurs the gender boundaries. What are you working on now?

AM: During lockdown, I have been pursuing a body of work that started with my latest solo show at Musée des Beaux Arts Le Locle in Switzerland, which included the figure of a Siren. Working with the Greek mythology’s man-eating siren, sitting on a mass grave of her victims, and flowers named after the sea god Proteus, led me to explore the iconography of the cemetery, making green wax hand sculptures holding flowers and candles, like offerings or altars.

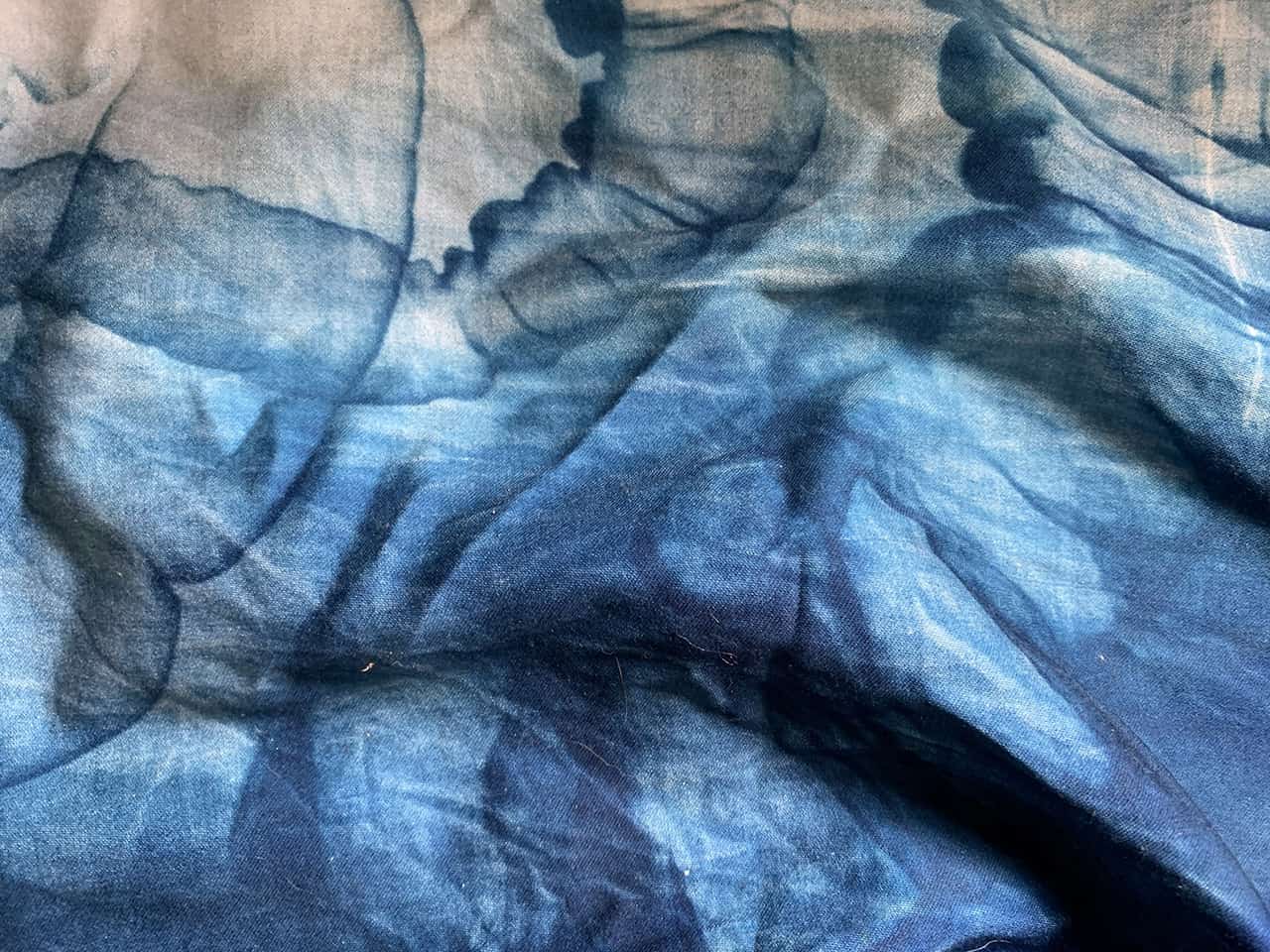

I have also started testing for a new project, that uses fabric cyanotypes with x-rays of the human body. So, I guess this time, between working with hands and the inside of our bodies, it’s pretty gender-neutral. Those were two projects I had started before the Covid-19 crisis but of course I am now questioning them in light of the current situation (working around the iconography of funerary objects, hands/touching…).

La Femme Fontaine, 2017, Materia Gallery

Cyanotype, Work In Progress

MM: You are not afraid of showing the human body as it is. Through photographing bruises, stretch marks, scars, and other ‘imperfections’, you show that they exist in everyone and should not be concealed. What are you protesting against? The stereotyped view of a female body and how capitalism taught us to admire it only in its artificial, idealised form?

AM: Yes, I am definitely protesting against the narrow capitalist ideal standards of beauty. But not only for women. I have photographed both genders and I think the pressure of looking in a certain way, the advocacy for light skin colour, skinny, hairless, muscular bodies, has damaged most people, disregarding their gender. I think the problem in bodily self-esteem has important repercussions and that being taught you’re too fat or too small or too tall or too hairy or too wrinkled should be fought against.

MM: The environments you create for your works can be perceived as uncomfortable. How do the viewers react to them and how would you like them to react?

AM: When working on an exhibition or installation I try to think about the space in relation to the body of the viewer. In addition to the subject and ideas behind it, I try to make it a physical experience. It is true that sometimes they have been read as rather intense environments, but then it really depends on the person whether they feel uncomfortable or not, I have had very different feedback in the past on the same work!

Offer To Proteus, Work In Progress

MM: How did the current situation influence your future plans and exhibitions? How do you spend your time whilst in isolation?

AM: While some projects have been postponed or cancelled, the group show I am part of in Leipzig at Kunstraum D21 is opening on the 28th of May and I should be part of the TIFF xfestival in Wroclaw in September. During the lockdown, I have been very lucky to be in the countryside, as I was visiting my parents in France when the lockdown started. I had some materials left from a show I prepared here last summer, so I have been able to keep making work and test new ideas. I am worried about the tough professional and financial times ahead, so I have tried to keep on working while I can.

Héraclès, 2018, Ratinger Tor

The article was created thanks to the Arts Council Emergency Response Fund: for organisations (non NPO). Contemporary Lynx organisation is supported by Arts Council England.