Katarzyna Kryńska “Silence of the Heart”

SK: The theme of the 6th edition of Vintage Photo Festival is ‘freedom.’ How did you come up with the idea to present the works of international artists in this context?

Katarzyna Gębarowska: Originally, we hit upon the idea inspired by this year’s 100th anniversary of the re-annexation of Bydgoszcz to Poland. Then, we were taken aback by COVID-19, the global crisis as well as the momentous reset for humanity. Freedom, which we’ve taken for granted, was strongly curtailed out of a sudden. We were witnessing border closures of whole counties and continents, restrictions in freedom of movement of people have undermined one of the foundations of the global village. Not only did the global pandemic limit this freedom of movement but also the whole spectrum of consumption tendencies, meaning the endgame of every company on earth and the driving force of the entire economy. In these last few months, our notion of freedom had to be truly re-evaluated and understood in the completely new light. For this reason, the exhibitions presented as part of this year’s edition of the festival address the subject of FREEDOM in various contexts, such as freedom from captivity, personal freedom, isolation, physical lockdown caused by the COVID-19 pandemic etc.

SK: How do the international photographers understand, interpret and comment on the theme of freedom? What kind of approach do they adopt?

KG: The exhibition of Paz Olivares Droguett from Chile tackles the concept of freedom in the age of perpetual confinement and the need to face parenthood during isolation. These poetic and intimate photographs chronicle the life of a family during the coronavirus pandemic.

The works of Parisa Aminolahi, an Iranian photographer, present another angle. Based on a visual contrast, this photographic documentation portrays the life in two geographically and socially remote places, namely in the Netherlands and Iran. The lack of limitations and carefree lifestyle of an immigrant are intertwined with the sense of responsibility for the parents in Iran.

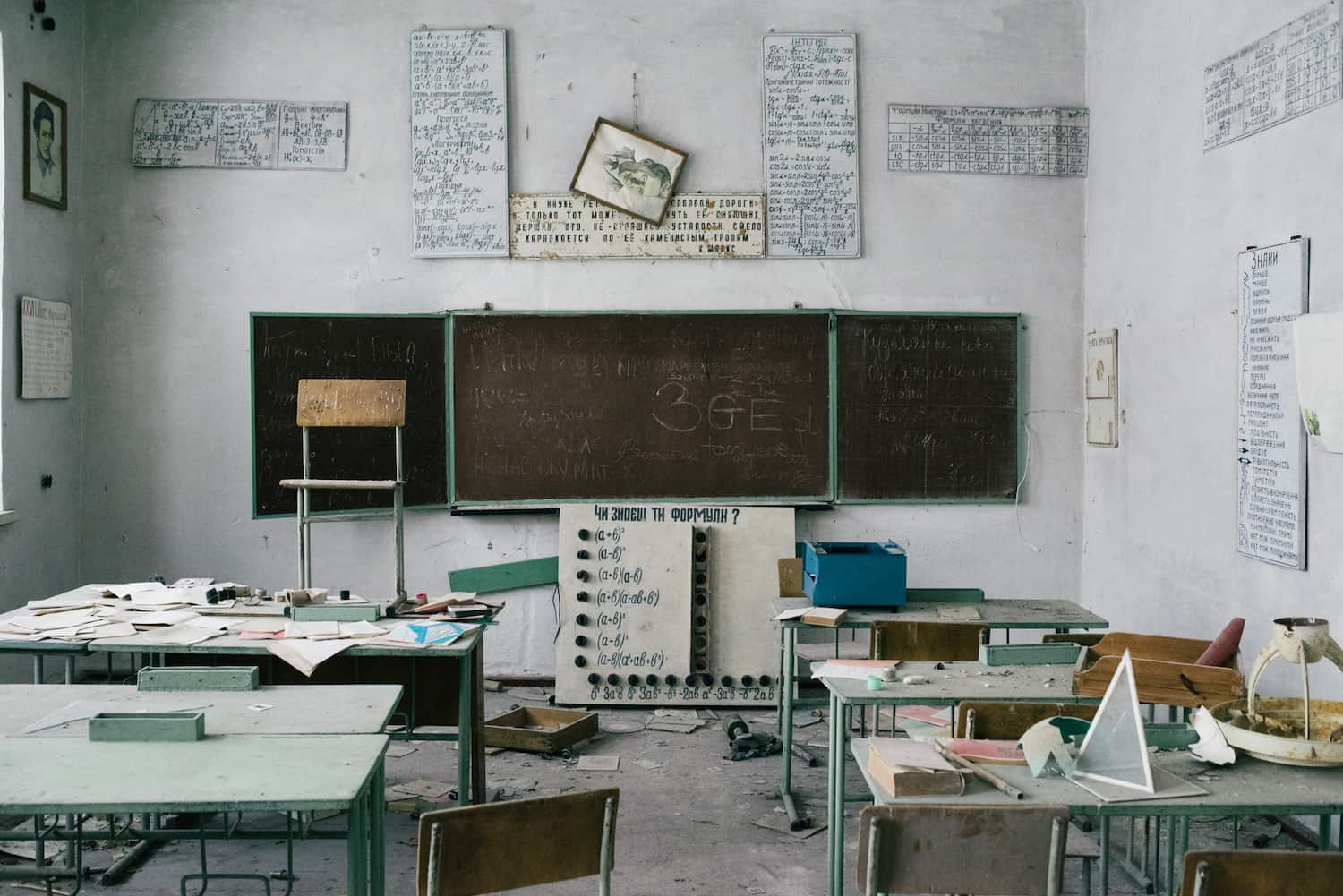

Another artist whose works will be presented during the festival is Maxim Dondyuk. His project about Chernobyl unites the past and present, explores the themes of memory, territory, atomic energy, and nature. Initially a contemplation of emptiness and silence of abandoned territory, the project turned into an exploration of the past that existed in Chernobyl long before the nuclear disaster: old films, family albums, postcards, letters – all these years the memories had been exposed to nature and radiation. What a fascinating reflection during the pandemic, when nature manifests its dire need for cleansing.

Maxim Dondyuk “UNTITLED PROJECT from Chernobyl”

SK: 6th Vintage Photo Festival juxtaposes analogue photography from the past with the contemporary works of young artists employing conventional techniques in an unconventional manner. What sort of ideas and usage of analogue photography techniques should we pay attention to this year?

KG: The exhibition titled “Threads and Light” by Marcelo Aragonese unveils the commentary on the current situation in Chile in the context of freedom. Social unrest triggered by poverty, poor life conditions and climate crisis caused the eruption of civilian protests. His photographic project combines analogue photography with textile interference. It is a project of similar, analogue photographs printed on canvas using the sublimation technique. The images are then hand embroidered and hemmed with fabrics that add colour to black and white photographs.

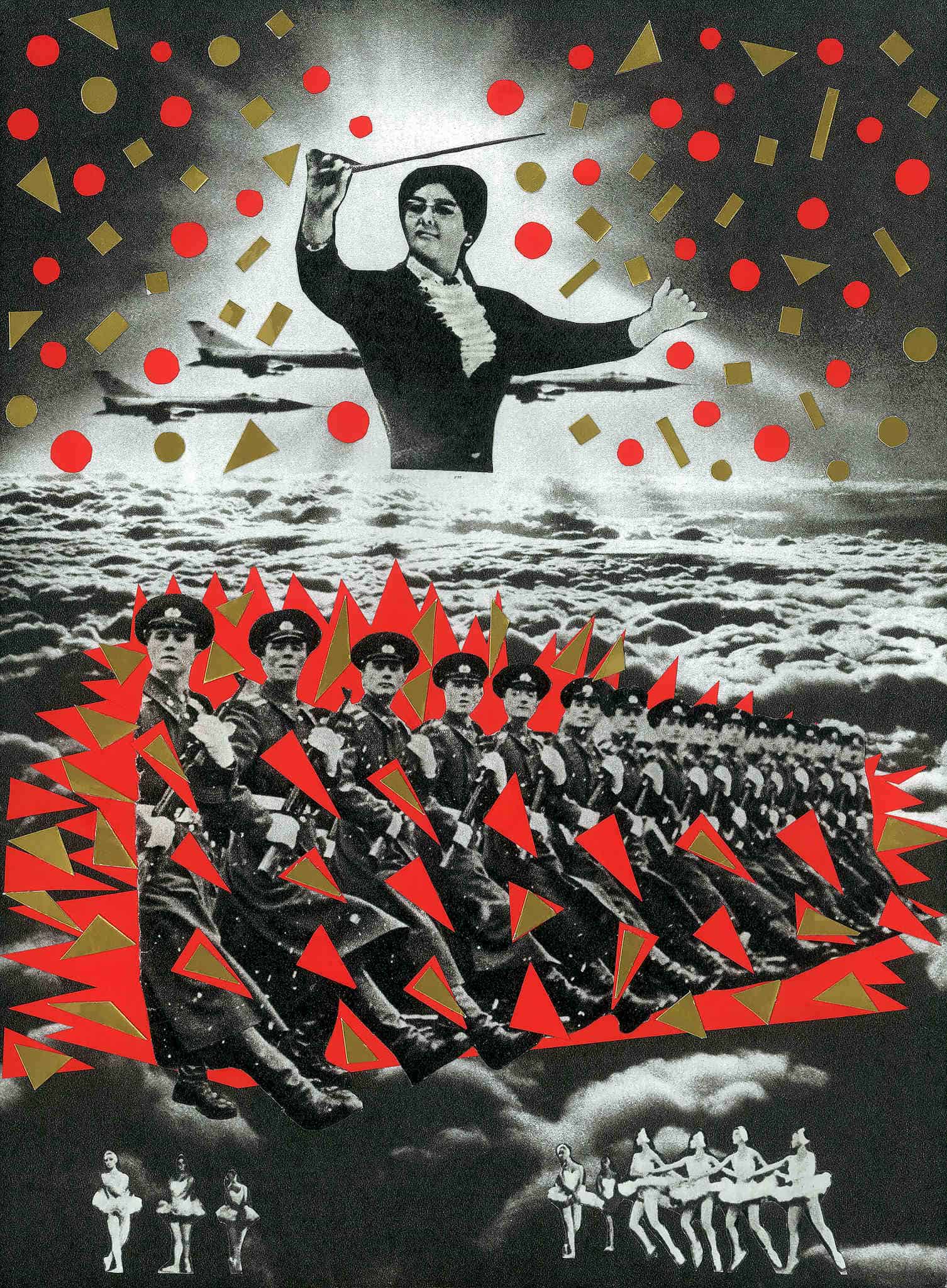

The series “Everybody dance!” by Masha Svyatogor brings together works that unfold around the artist’s reflection on the USSR and the notion of what’s “Soviet”. They are based on the photographs found in numerous print issues of the “Soviet photo” magazine, in other words the visual material the Soviet government used to represent itself building its “ceremonial” image. It is interesting to mention that the artist creates her photomontages manually, deliberately abandoning digital technologies, which evokes the metaphor of the fabric of history. Masha literally cuts this “fabric” – she disassembles the official images of representation and uses them to make her surreal, ornamental pictures with utmost attention to detail.

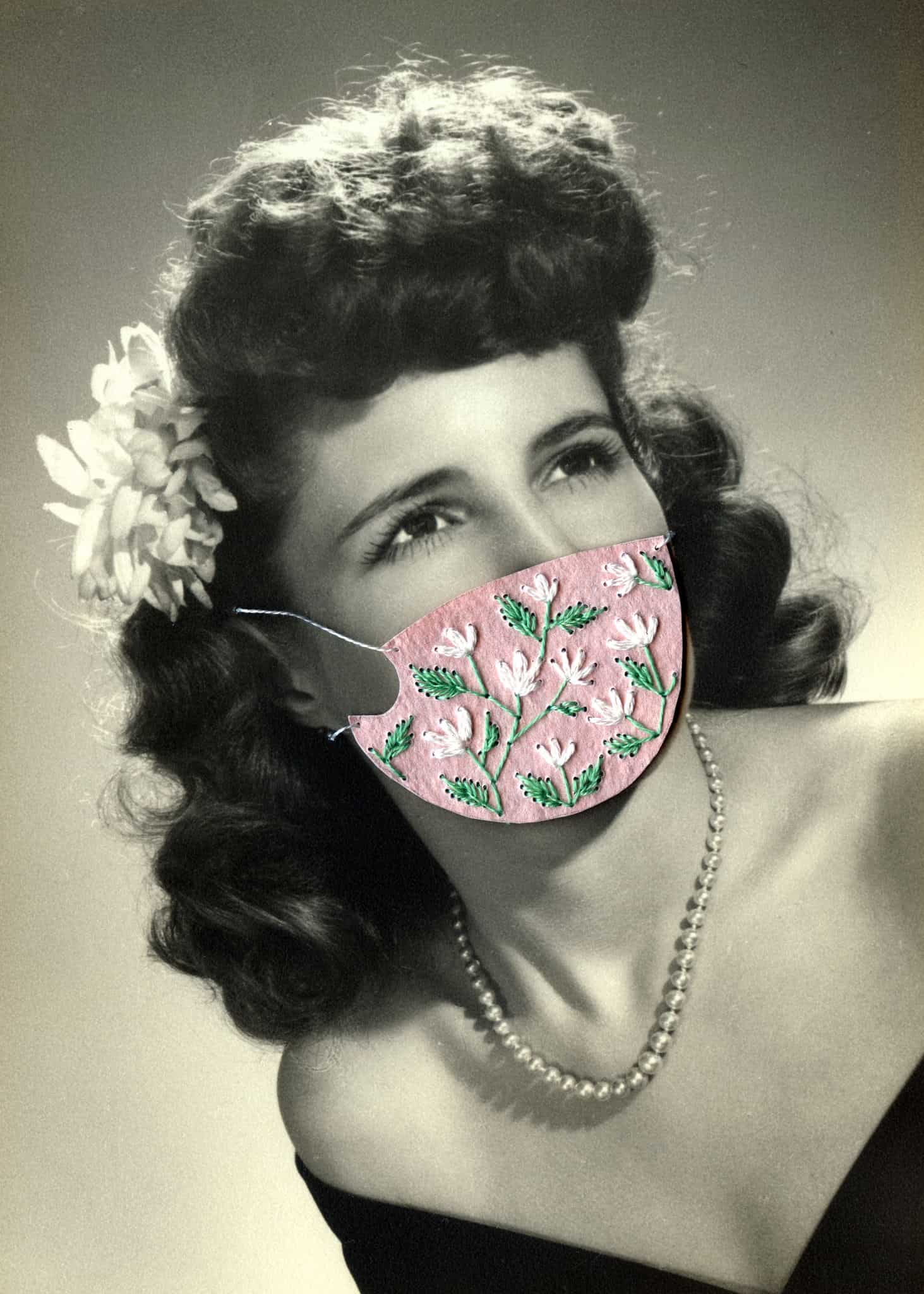

Brand-new reality provided inspiration for the artist Han Cao. In her series “Quarantine Collection,” the artist hand-embroiders masks onto vintage photographs, which makes them relevant even after all these years.

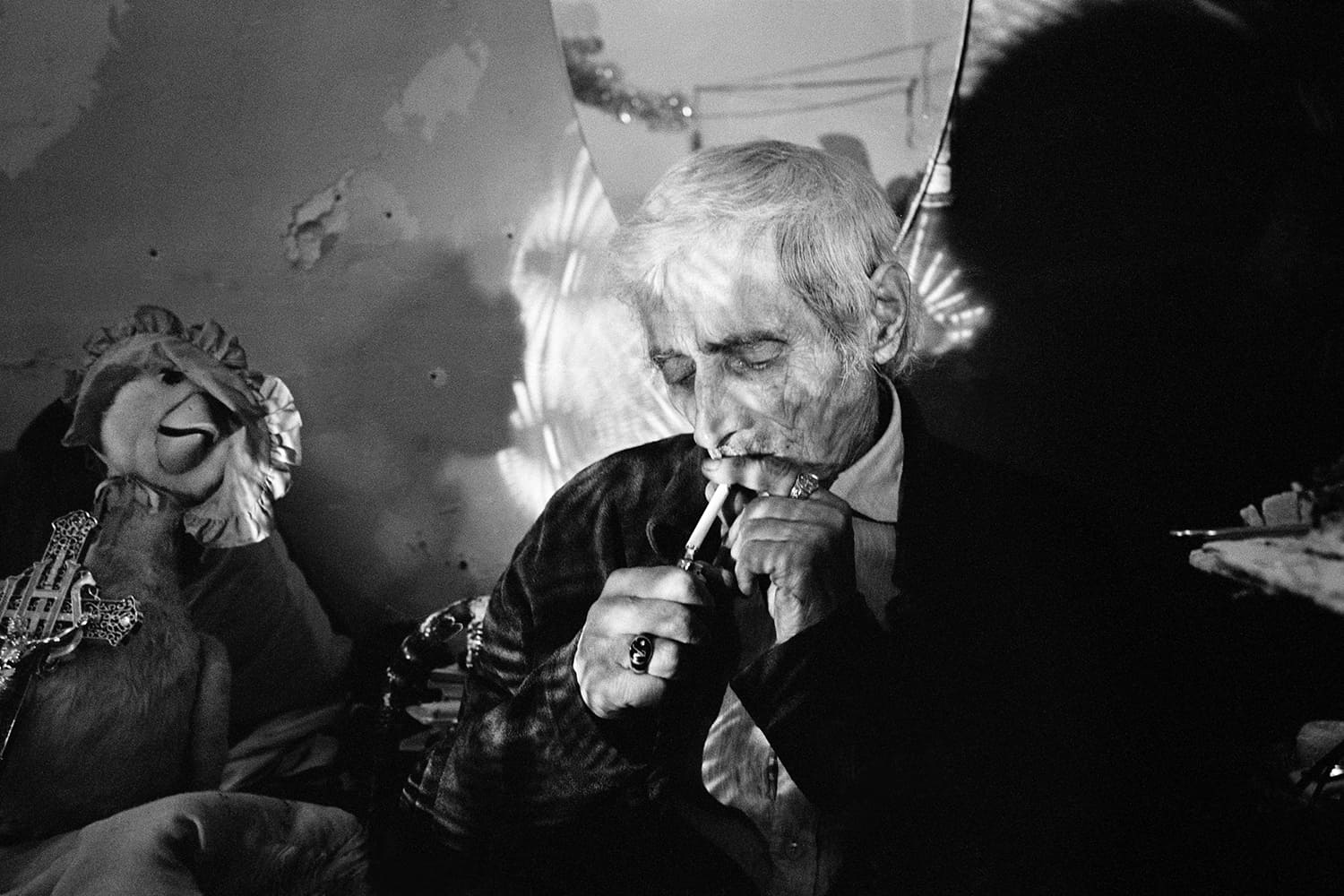

Ciro Battiloro “Sanità”

SK: One of the festival exhibitions shows pictures taken on the streets of Bydgoszcz in the 1920s and 1930s by the pioneering street photographers. Who were they and what did they capture on camera?

KG: Life gained momentum in the 1920s and it shows on the photographs themselves. Instead of posed, highly stylized and static pictures taken in the atelier, photographers went out into the streets, breathing new life and authenticity into the images. They captured people running by, in motion, in a hurry. The revolution was associated with the launch of the 35mm Leica camera, which premiered at the fair in Lipsk in 1925. Seven years later the updated version of the camera with an attached viewfinder was released. From 1925 onwards, the Leica photographers flocked into the urban landscape, taking photographs of passers-by with no prior warning, accosting people, handing them a piece of paper with an address where they could collect developed photographs. The process was lightning fast – you popped by the photographer’s studio to get your prints on the same day the picture was taken, after a family walk, romantic date or other errands.

In Bydgoszcz, the Leica photographers approached people on the Mostowa or Długa Streets and on the Wolności Square. They were the ones who brought the streets of Bydgoszcz back to life. People in their photographs look naturally against the backdrop of a hustling and bustling city. There were four friends: Stanisław Springer, Bolesław Langer, Jan Zaremba and Józef Wiedeliński. In the summer, they relocated to the seaside, heading for Hel, Ustka and Jastarnia. Two photographers were walking on the beach taking pictures, another one developed the film. People could collect their pictures in an ice cream booth as they were coming back from the beach.

Years later, these quick snapshots are the portraits of the city and its inhabitants. The photos from private albums have acquired the status of documentary photography. They provide records of past interiors and squares, shop windows, coffeehouses, signs, customs and fashion.

Han Cao „Quarantine Collection”

SK: How did you come up with the idea to engage citizens of Bydgoszcz in the project and encourage them to find family photographs in their own albums?

KG: For years, the Farbiarnia Foundation has overseen a number of projects which involve the citizens of Bydgoszcz and their own family archives. The initial project of this sort was our book titled “Kobiety Fotonu” (“The Women of Foton”) accompanied by the exhibition of photographs depicting the female workers of the Foton manufacturing plant – the second largest factory in Poland that specialized in the production of the photographic materials. The aim of the project was to reinvigorate the interest in the factory and its workers. Another similar big project of ours was the publication “Zawód: fotografistka” (“Profession: a female photographer”) that focused on women working as professional photographers in Bydgoszcz in the late 19th and early 20th century. The book and accompanying exhibition captured private lives and careers of these pioneering female photographers. In addition, “Archi(w)tektura Henryka Nahorskiego” (“The Archi(ve)tecture of Henryk Nahorski”) is the collection of archives discovered by the photographer’s family. We were fortunate enough to rescue these old photographs from obscurity and give them a second life.

Parisa Aminolahi “Tehran Diary”

SK: Is there a common denominator uniting photographers who prefer using analogue techniques?

KG: Analogue photographers tend to be precise, and their shots well-considered – after all, the number of pictures they can take on film is much more limited than in case of a digital matrix. On the other hand, lots of people, especially younger generation, resorts to the use of analogue techniques not for the sake of said precision, but the element of surprise, serendipity and enjoyment. Oversaturated with digital images, generation growing up with smartphones turns to analogue mediums to conjure their subjective recollections which don’t necessarily have to be technically flawless (so they often use old expired film rolls etc.). The point is to “have their own voice,” something authentic, unique, different from the iPhone app available to the millions of other people.

Marcelo Aragonese “Threads and light”

Contemporary Lynx is a proud media partner of the 6th International Analog Photography Lovers Festival, Bydgoszcz.

The festival takes place between 18 September and 3 October 2020.

Masha Svyatogor “Everybody dance!”