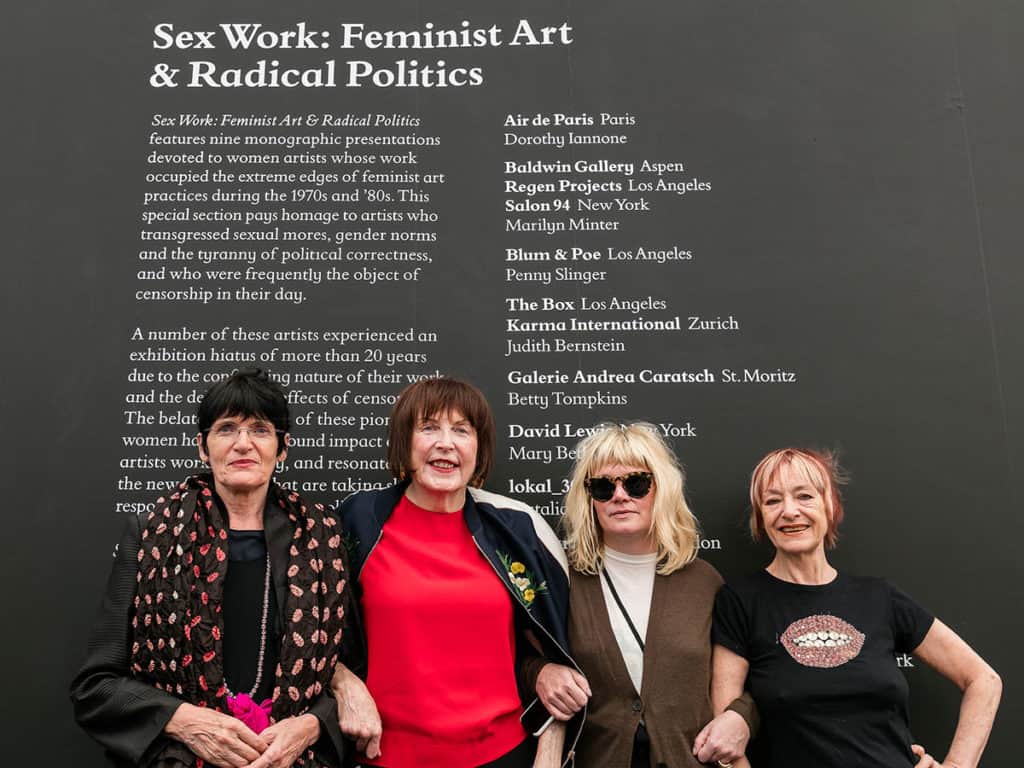

Blum & Poe, Sex Work: Feminist Art & Radical Politics, Frieze London 2017, Photo by Mark Blower. Courtesy of Mark Blower/Frieze

The Frieze art fair features almost two hundred contemporary art galleries every year. It raises important questions, confronts the obstacles that arise when challenging the status quo, and plays with the tastes of its spectators. Since the Internet has started to become a surrogate for reality, we have been engulfed in a game of excuses. Watching art should be connected purely with a one to one experience and no substitutes can replace this psychical contact.

Simone de Beauvoir’s book, ‘The Second Sex’, and especially the profound importance of her statement: ‘One is not born but becomes a woman’ has left a hallmark on present day discussions on feminism. According to de Beauvoir, being a woman ‘is not a natural fact’, but a result of many circumstances which have occurred throughout history. There is no psychological or biological destiny for women – young girls are brought up to become women. Before a child has gained consciousness, we find society engaged in implementing a series of behaviour and social roles on it. It is also useful to illustrate that in every era men have been found to usurp and hold power. During the Middle Ages and the Renaissance, female physicians were in possession of uncommon knowledge; they knew whatever there was to know about medicines and herbs. They then found this taken away from them as men started taking over the profession of medicine. The witch hunts were very likely a way for men to keep women away from medicine and the power it conferred upon them. Three centuries ago, statutes were drafted by men that prevented women who were imprisoned, fined, etc. from practicing medicine unless they attended certain schools, which, in turn, did not grant females admission. This always makes me think of the reason why gender stereotypes and traditional images of women have been grievously perpetuated across all the centuries.

Sex Work, Frieze London 2017, Photo by Mark Blower. Courtesy of Mark BlowerFrieze.

During this year’s fair, my attention was particularly captured by ‘Sex Work: Feminist Art & Radical Politics’ curated by Alison Gingeras. Not only because of the works by legendary Polish artist Natalia LL on display, but also for the bold concept behind the exhibition. ‘Feminism is a word that gets used and abused in the culture by politicians and corporations. It’s important to understand that feminism itself is not a monolithic movement. It is very plural and very diverse’ comments Gingeras in the official video. For me, the design of the space was equally impressive as the distinctive explicit subjects and the diversity of approaches – from bold political criticism in Judith Bernstein’s works to more spiritual, Dali’s jewellery-like surrealistic pieces of Penny Slinger. Whatever we might think, this feminist ghetto was marked with the intention that sex is a human issue and not just feminine one. The complexity of history is dedicated to powerful female artists cultivating feminist practices since the 1960s and whose works were very often the subject to censorship. We can call them pioneers or warriors, because they continue to have a profound impact on many artists working today.

When speaking of feminism, it is important to point out ‘Artists in Residence’. A.I.R Gallery was founded in 1972 as the first not-for-profit, artist-run exhibition space for women artists in the US. At the time, works shown at commercial galleries in New York City were almost exclusively by male artists. Feminist art history’s timeline of its ground-breaking contribution has made women today speak up for their rights and openly discuss sexuality. A.I.R.’s history counts numerous radical artists, including Judith Bernstein, Louise Bourgeois, Agnes Denes, Mary Beth Edelson, Ana Mendieta, Howardena Pindell, Sylvia Sleigh and Nancy Spero. Judith Bernstein was a prominent guest at this year’s Frieze Fair; well known for her dick paintings, she fearlessly says: ‘My work is sexual, my work is political and my work is feminist. It has visual impact, is fun but also dead serious (…) my work is actually very sociological. It has a lot of anger and rage but it also has play and it also has fun’. Bernstein is observing women and treats them as the centre of the universe. Is it too crude and direct? I believe that it makes a point. The artist has valuable inputs for our ongoing dialogues on importance and the value that women have. Her hybrids between a dick and a screw show a playful debunking of the statement that genitals determine gender.

lokal_30, Sex Work section, Frieze London 2017, Photo by Mark Blower. Courtesy of Mark Blower/Frieze.

Who’s Afraid of Natalia LL? In the 1970s, she acknowledged that free speech should be very challenging. At that time in Poland, Natalia LL co-funded the artist-run gallery PERMAFO in collaboration with Zbigniew Dłubak, Andrzej Lachowicz and Antoni Dzieduszycki. Her exhibition ‘Intimate Photography’ was shut down after two days. ‘I explained, that this is the human body, everyone’s body is alike, men, women, and it’s nothing, we’re all copulating at times, even right now millions are copulating and that’s okay’ – because of strict censorship – both political and moral – no explanations helped save the show. Conceptualism has always been important to her work. She bases many of her performances on dialogue between the psyche and the body, drawing from personal experiences which mark a dimension of universality. Surprising insights that can help distinguish her approach deal with forms of existentialism and transcendence, as well as taking inspirations from the Bible.

Most recently, her art was featured at the Frieze Fair. Projects titled ‘Consumer Art’ and ‘Post-consumer Art’ both imply activities associated with consumption appearing as something erotic. It refers to period in Polish history when products showed on video – bananas, sausages, whipped cream, milk – were unavailable for many. Natalia LL made this into her critical response to The Polish People’s Republic (Polish: PRL) and created an internationally recognised dissent against Communist control. The artist created very suggestive and disturbing pieces which do not lose their vitality even after more than thirty years. Also, I have noticed that ‘Intimate Registration’ from 1968 still leaves a guilty flush. Why? To my mind, Natalia’s concept of ‘permanent registration’ capturing moments of everyday existence challenged a culture by illuminating the issue of the commodification of women’s bodies in pornography. Lokal_30 Gallery, which was responsible for showing Natalia’s body of work, put this in terms of the basis of existence and human nature.

Frieze London 2017, photo Contemporary Lynx

Also worth mentioning are the monumental photographs and paintings of intercourse by Betty Tompkins, which were so explicit that no gallery would show them at the time. Only in 2002 did she exhibit her ‘Fuck Paintings’ at the Mitchell Algus Gallery in New York, marking the end of an almost three decade long gap from exhibiting those censored pieces. Their subtle look reminds me of early photographic experiments in the mid-19th century with the colloidon wet plate process, which produces images of eerie, mysterious beauty like a Sally Mann still. Who, incidentally, also experienced censorship when ‘The Wall Street Journal’ censored the eyes, breasts and genitals in her photo with black bars.

Secondly, I also wanted to discuss Renate Bertlmann, whose works were covered with a barrier of phone cameras. The fetishistic objects which she presented blurred the stereotypes given to masculine and feminine objects. Latitude to try out new juxtapositions – penis sculpture dressed like child doll, kissing condoms or ‘dildo cactuses – left me without any doubts regarding artistic freedom – experiment and risk are necessary tools to find out our own possibilities and limitations.

Alison Gingeras’ selection of works left me filled with a curious joy. As a woman, she showed that the sex is a human issue and feminism has built a massive part of the history of art and of history in general. It is a pure celebration not just of the artists, but also the galleries who were brave enough to support them. In 1989, the artist-activist group Guerrilla Girls launched their iconic campaign ‘Do women have to be naked to get into US museums?’ and I feel that this might be a good conclusion. The ‘era of strong women’ is spreading slowly but surely, and in few more years I hope that we reach a point where no men question women’s choices, and equality is as natural as breathing – in art and everyday life. Being free feels the same as being strong.

Written by Marta Klara Sadowska

Natalia LL, Frieze London 2017, photo Contemporary Lynx

Richard Saltoun, Sex Work section, Frieze London 2017, photo Contemporary Lynx