The Mnemosyne Atlasis an unfinished work, actually a repository of images (Bojarska, Katarzyna 2012) collected by Aby Warburg from 1924 to when he died in 1929. Known only from its photographic reproductions, it is a record of a creative and scientific process, which became for art historians an important contribution to the extremely prolific thought within their own fields, and also to the contemporary theory of image. The most notable event which constituted the “discovery” of the Mnemosyne Atlas is an exhibition entitled The Atlas: How to carry the world on one’s back? created in 2010 and curated by Georges Didi-Huberman. The exhibition consisted of four “chapters”: Knowledge Through Images, Piecing Together the Order of Things, Piecing Together the Order of Places and Piecing together the Order of Times. Didi-Huberman confronted Warburg’s panels with the works of contemporary artists of the time. Katarzyna Bojarsksa has noted that the form of the exhibition “enables to show Warburg’s notion of a discontinuous and non-linear time, in which one can compare and juxtapose artworks and paintings from different epochs and places, to reconfigure space, to redirect it and place emphasis in a different point, introduce non-linearity in a place where we thought there was continuity, to reunite it, where it seemed cracked an incoherent“. (Bojarska, Katarzyna 2012: 208).

Speaking of the Atlas through the exhibition seems more accurate than an attempt on a scientific interpretation. Especially as, according to Didi-Huberman, it functions in two orders – the order of knowledge, understanding and interpretation, and the aesthetic order, where it constitutes an artwork made up of someone else’s paintings.

With his Mnemosyne Atlas Warburg broadens the scope of the general discourse on the history of art, and a microblog is a popular medium which is often used by artists and curators like Thomas Mailander, who is active in the field of art and defines himself as an artist in a nearly modernist sense: “My work has been digested by the Internet and has reappeared. It’s cool, but at the same time I’m fighting for credit, too, because I’m an artist. It’s hard for non-professional people to understand – how can you take pictures from people, reuse them, and at the same time fight for your signature?”. We assume that one of the main components of Warburg’s categories, the notion of Nachleben, may be treated as a key to the interpretation of all the activities and strategies described here. The notion of Nachleben, translated as a journey or the survival of an image, is, according to Didi-Huberman, “the fundamental problem which his archival research addressed, and for which he created the library that bears his name in order to grasp its sedimentations and shifting grounds”. A sort of basic cultural reminiscence is included in his philosophy of images: an infinite stream of images recorded in an unconscious collective memory.

The Atlas and Mnemosyne

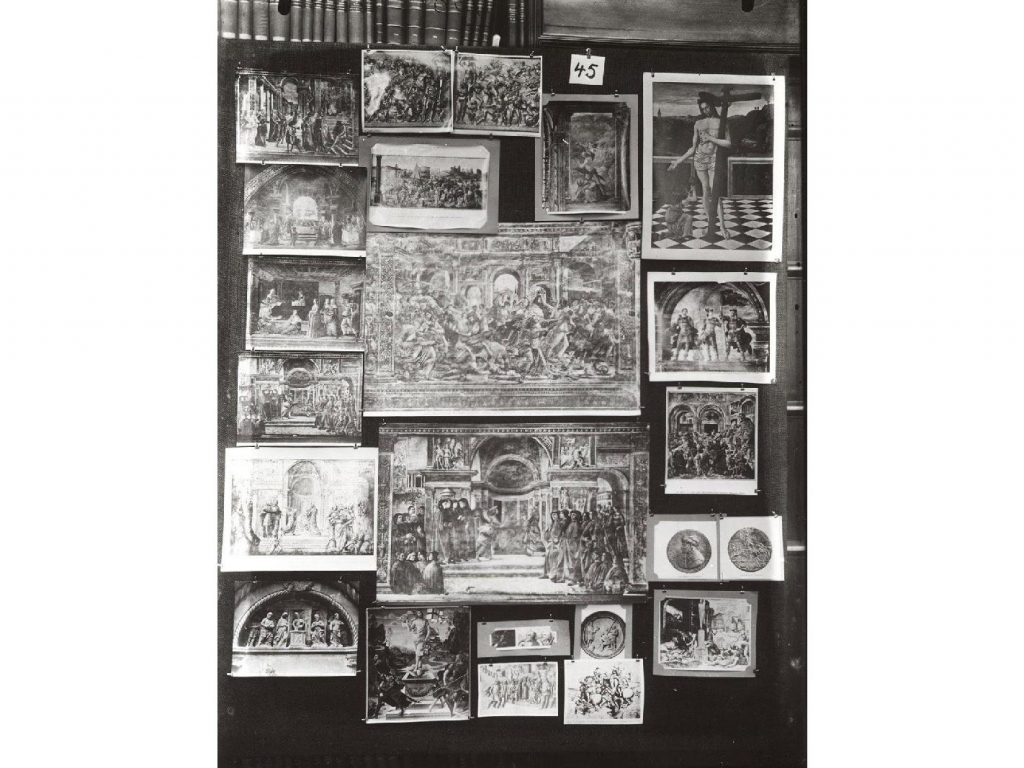

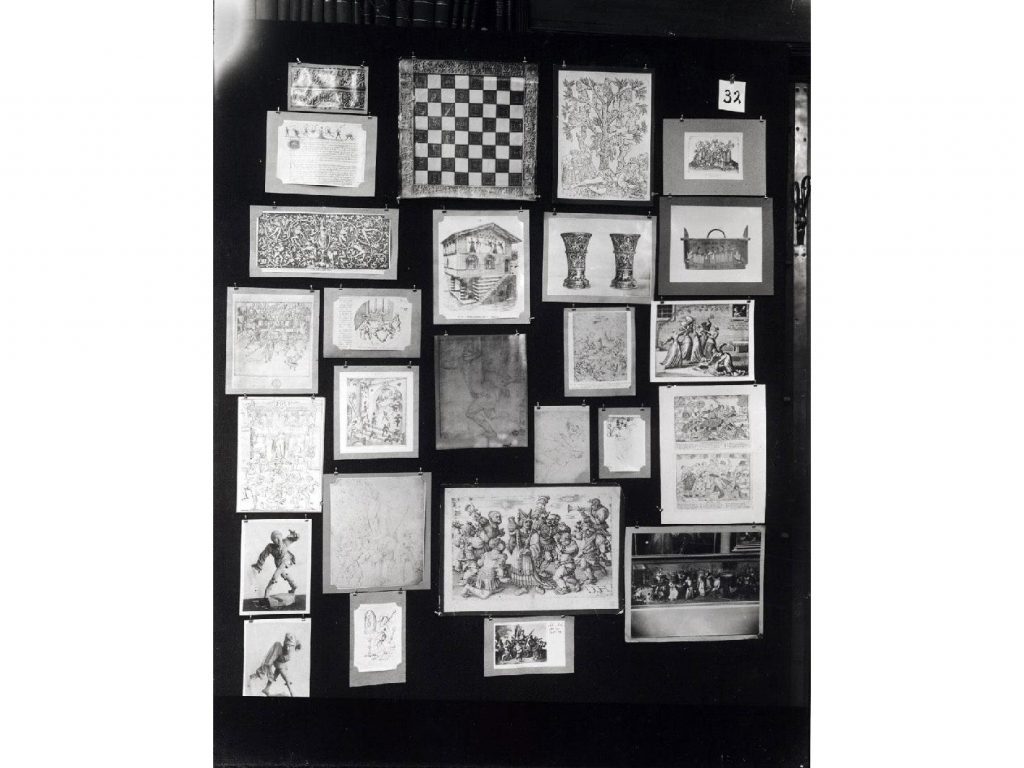

Warburg’s project includes 971 individual photographs and small black-and-white photographs of panels (boards with arranged photographs) accompanied by laconic titles resembling today’s hashtags or keywords related to content search engine optimalisation (SEO). The panels were arranged and photographed, followed by deconstruction, rearrangement, and then being photographed again. Each board depicts one idea or issue. In the panels, images of highbrow and popular culture live side by side, and each image presents the same value in a grand project of piecing together the world which is falling apart.

In the Introduction to the Atlas, Warburg outlined the goals he wanted to achieve very precisely, although their interpretations may turn out to be quite broad. “The aim of the Mnemosyne Atlas is to illustrate a process which may be defined as an attempt to assimilate expressive values crammed into our minds through the creation of images“, he writes (Warburg, Aby 2011: 110).

Aby Warburg, Mnemosyne Atlas

Giving some thought to the difference between the creation of images at the beginning of the 20th century and now, it is possible to notice a cohesion of the methods of illustrating through the processes described by Warburg. According to him, they have been inscribed in collective memory, and we can bring them out not on the basis of chronological reconstruction, but on the basis of a systematic ordering according to logic, intuition and gesture. The deluge of images, at the same time devoid of the source, results in the fact that one of the methods of ordering them is to use a user-friendly interface allowing to pin an image and save it in relation to other images. This atlas-type interface is provided by the Internet blogging service Tumblr, and by the book. These seemingly distant media show a startlingly great deal of similarities:

1. By using the convention of the atlas, which according to the definition is a collection of maps, charts, illustrations, boards etc., issued in the form of a book or an album. By implication, the atlas begins in an arbitrary way; it is not linear and can be read in random order.

2. A work on photographic archives. The creation of relations between the images is possible thanks to the practice of putting reproductions together – the appropriation of a work of art in the form of an image. The creation of the Atlas is only possible thanks to the existence of a mechanical reproduction.

3. A combination of images without footnotes. Thanks to resigning from texts, from the information establishing the context, the presentations begin to act on the viewer either on the basis of reading cultural codes or on an aesthetic or visual one.

4. The combination of images according to a key of an imagination leap, repetitions, flippant typology of motifs, and visual similarity.

5. A trial-and-error method of creating constellations of images, putting them together and checking if they work together, the temporariness of material objects, followed by reconfiguration and documentation. All this is governed by an internal logic of images.

6. The involvement of the viewer who is included in the process of creating meanings.

Warburg vs. Tumblr

The Mnemosyne Atlas referred to deep structures: collective memory, the psychology of an individual in line with the spirit of classical psychoanalysis – for example, sublimation and desublimation. The books or blogs under analysis in this essay stop at an earlier stage, placing emphasis on things that act on the surface, in terms of a visual layer.

Blog strategies

Tumblr, as one of the most popular blogging platforms, is interesting in the context of Waburg’s creation of new relations because it lies somewhere between an exhibition platform and a social networking medium and thus is open to commentary. Combining text and image allows Tumblr to take part in two discourses at the same time. The users combine messages in the form of a moodboard, similar to using a cork wallchart, editing the available visual material and deciding on the kind of interdependence similar to that which occurs between the elements of a puzzle. Tumblr is used consciously by both artists and users who simply wish to share something with their viewers, without the need to operate on meta levels inherent in the phenomenon of writing blogs.

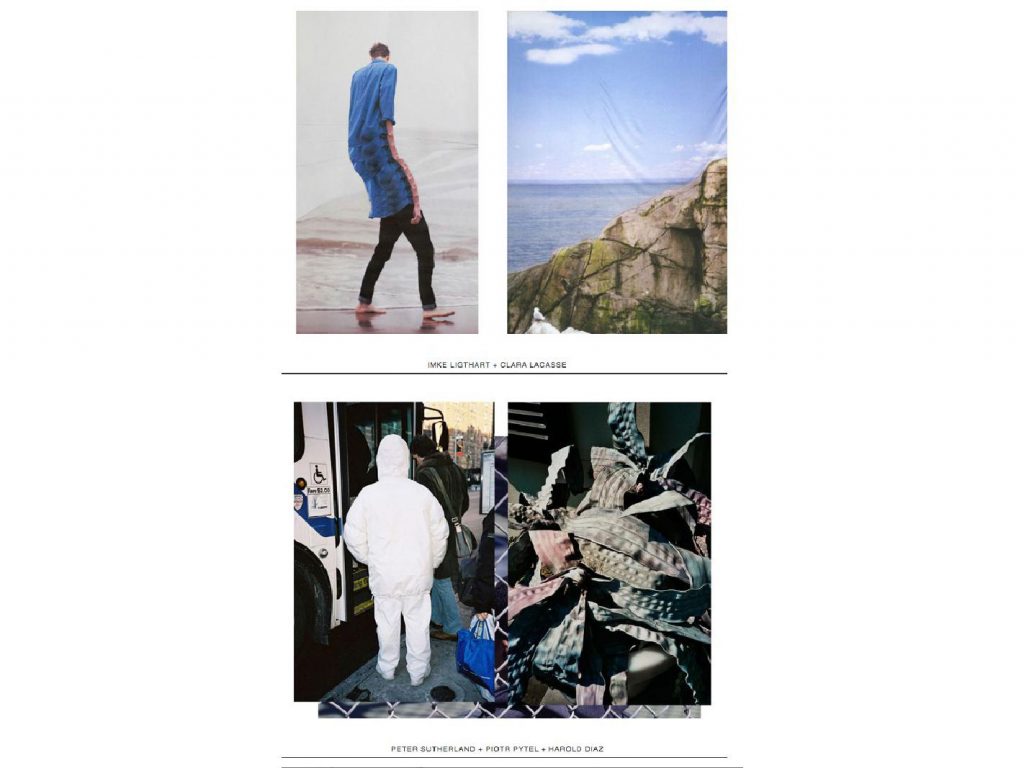

Tumblr is a platform where original creations constitute a minority. However, curators’ activities are supported on a large scale. A lot of blogs are moodboards and collages assembled from images, scanned images, cut-outs or texts available on the platform. The blogs are created as a result of making visual choices. The narratives created in such a way are usually asynchronic, non-linear, and put together on the basis of subjective hierarchies. The internal logic of these blogs is not always easy to deduce when one post consists of a dozen of images, dozens of stimuli and constitues a stream of consciousness or plays the expressive function of an internal mental image — as in the case of Kex. The strategy of placing images next to each other may also be visible in a more storage-based approach — as in the case of the MWAH blog-storage: where the author-curator, choosing from materials sent in by photographers, selects images by one author or another with the use of their own internal selection engine, and joins them into a composite, thus creating a new visual value.

MWAH paper

Due to the fact that Tumblr is a social networking platform, it is possible to draw analogies to social behaviours related to methods of using images. The collection, exchange and passing forward of images-objects or images-messages and other strategies emphasise the utility of images favour de-contextualisation processes. The whole community is the owner of an image, and the loss of control over an image and its original context is inscribed into the platform’s architecture. It is as in the case of Magdalena Świtek’s works — the photograph of her minor daughter, who was part of a documentary titled Pestka (Seed) has rapidly been reposted onto numerous blogs where it often becomes a part of an erotic narration under the banner of male gaze.

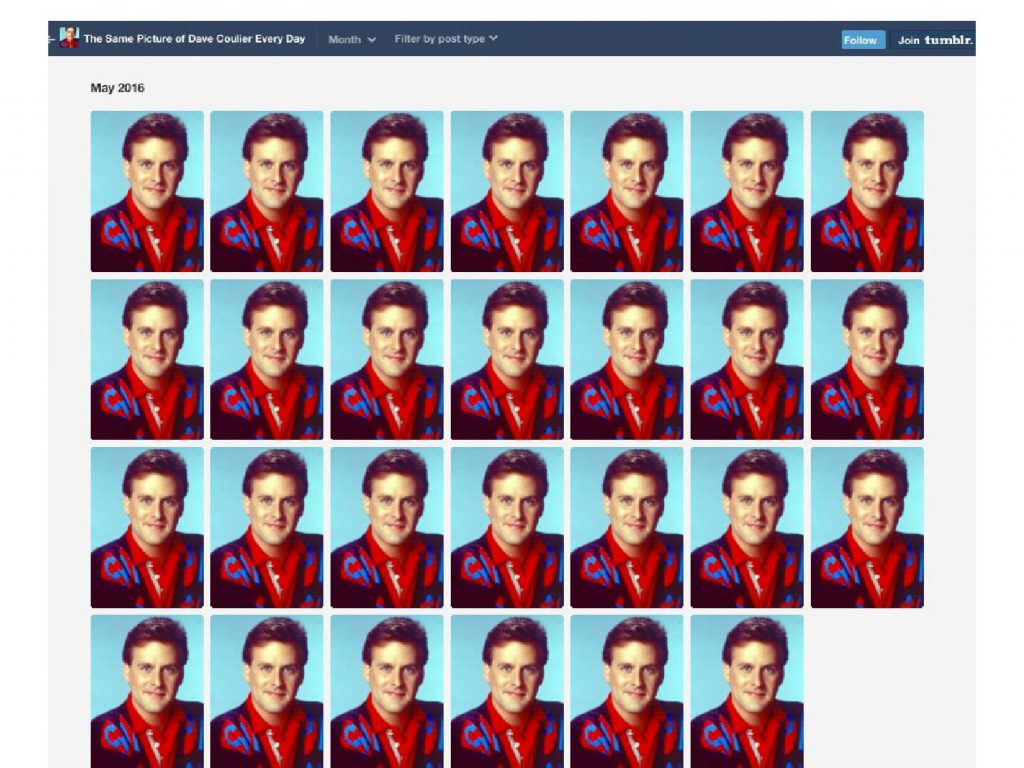

Digital collecting is yet another strategy of using an image which leads to the creation of specialised and curious typologies. These collections bring to mind Various Small Fires and Milk and other works by Ed Rusha. Celebrities on Old Computers, Things Fitting Perfectly into Things or Awkward Stock Photos are only some examples of these specialised collections. A blog entitled The Same Picture of Dave Coulier Every Day constitutes an interesting aberration to this convention. The portrait of Dave Coulier, famous for his role in the sitcom Full House, repeated 1645 times goes beyond typology and falls within the scope of intentional copying.

The Same Picture of Dave Coulier Every Day

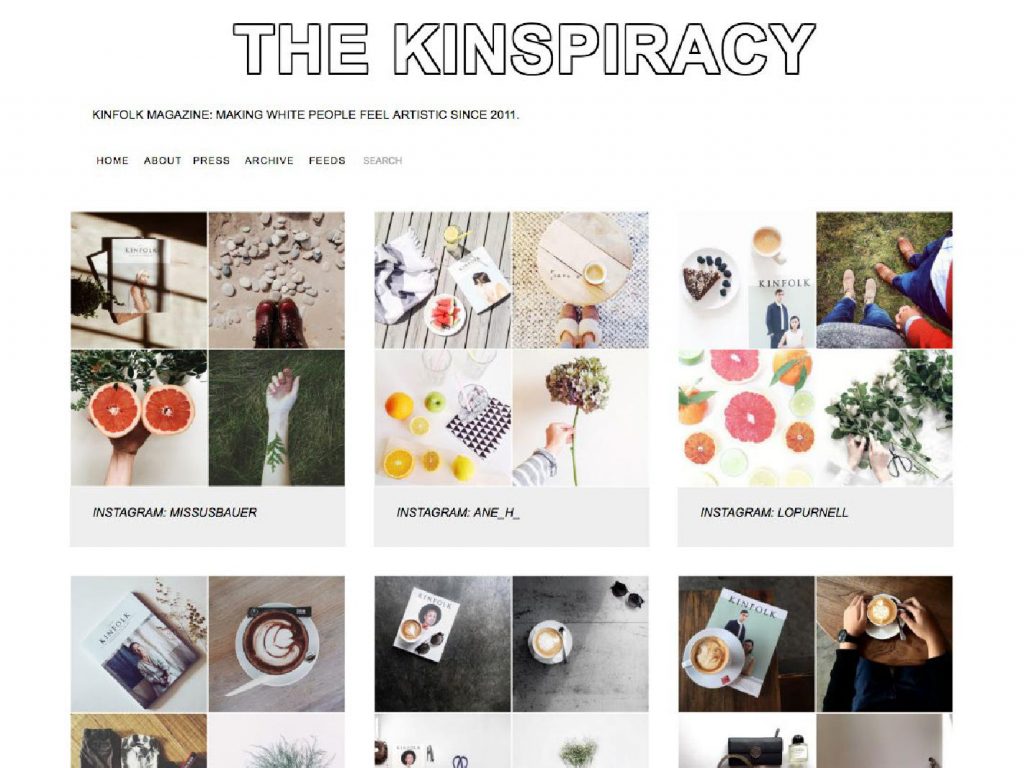

Tumblr is a place of pointing to and revealing repetitive motifs. Convention is the curator’s choice here which places the author on a specific aesthetic continent. Tumblr allows for the creation of a visual space which the author would like to be associated with, and thus to be taking part in visual class struggle. A blog entitled The Kinspiracy is a good example of this. The blog is devoted to the collection of visual material inspired by the aesthetics of the “Kinfolk” magazine. “Four images. One instagram account per set. A whole lotta the same shit. Welcome to the kinspiracy“. The blog features instagram pictures of the readers of Kinfolk in settings resembling the desaturated still life pictures from “Kinfolk”. The Kinspiracy reveals a convention and a cliche, pointing to the fact that people take photos of the same things in the same way, and it is mnemonics in its purest form.

The Kinspiracy

Tumblr provides a wide spectrum of purely visual comparisons. A spectacular example of this is Bowiebranchia (a portmanteau of Bowie and Nudibranch), a blog combining the images of various poses assumed by the musician David Bowie with images of the representatives of gastropods, in such a way that the colours on both images match. This subtle manipulation of context is pleasurable simply for its finding similarities in such distant species. It is possible to speak of the I’m Google blog on the basis of the logic of visual resemblence. Created by artist Dina Kelberman, it is an infinite scroll through a sequence of images changing smoothly into one another. These smooth changes resemble a game of visual Chinese whispers and are based on both the visual proximity and the internal logic of conducting a narration by an author-curator. Choosing items from the Google graphics repository, Kelberman moves from an inflated pool filled with water to a squash court in just a few dozen photographs. I’m Google balances on the verge of a script of visual deformations, but the curator’s choices of the blogger are clearly visible, mainly in the points of a gradual change in motifs — we can see a gradual distortion of a message, a gradual focus on, for example, a specific colour or an obsessive pursuit of a specific motif (water, inflated elements) and the rejection of the rest — the curator has made her decision.

Dina Kelberman, I’m Google

Mailaender’s and Warburg’s metalevels in times of the Internet

The difference between collecting visual materials on Tumblr and on platform-notebooks (like eg. Pintrest) or a book publication lies in the fact that in the case of the latter, the collection is closed after putting together a sufficient volume of material. It may now become a collection in its purest sense — it is not a stream of images built on indefinitely. Tumblr, however, remains open; the collection may be expanded, and its completion usually results from abandoning the blog and a loss of interest rather than completing the process intentionally.

The works of Thomas Mailander are based on closing such collections. It may be assumed that as an art historian, Aby Warburg accumulated meanings and, at the same time, succeeded in forgetting the images that do not match the set. A question of what happens to the images that were left out arises.

The answers can be found in the works of this French artist. His Fun Archive, created since 2000, consists mainly of photos found on the internet and sent in by frineds. The artist collects photographs, which as a rule were taken by amateurs, whose distinctive feature is a gesture, a situation or their comic nature, as Warburg would say. The rest, the residue, are failed jokes, spoilt frames, and embarrassing situations. Maiaender places them in the domain of art again, using selected artistic strategies. His strategies include refining and giving the aspect of uniqueness to images that had been digitally copied innumerable times with the use of non-silver photography techniques (e.g. cyanotype) or by creating ceramics. The artist intentionally assigns his signature, gesture and inscription to anonymous photos.

The publication of the photographs in the form of a book is what is most interesting to us. He comments on the status of paper publications in the era of global network, and at the same time, drawing ideas from Internet-based publication strategies.

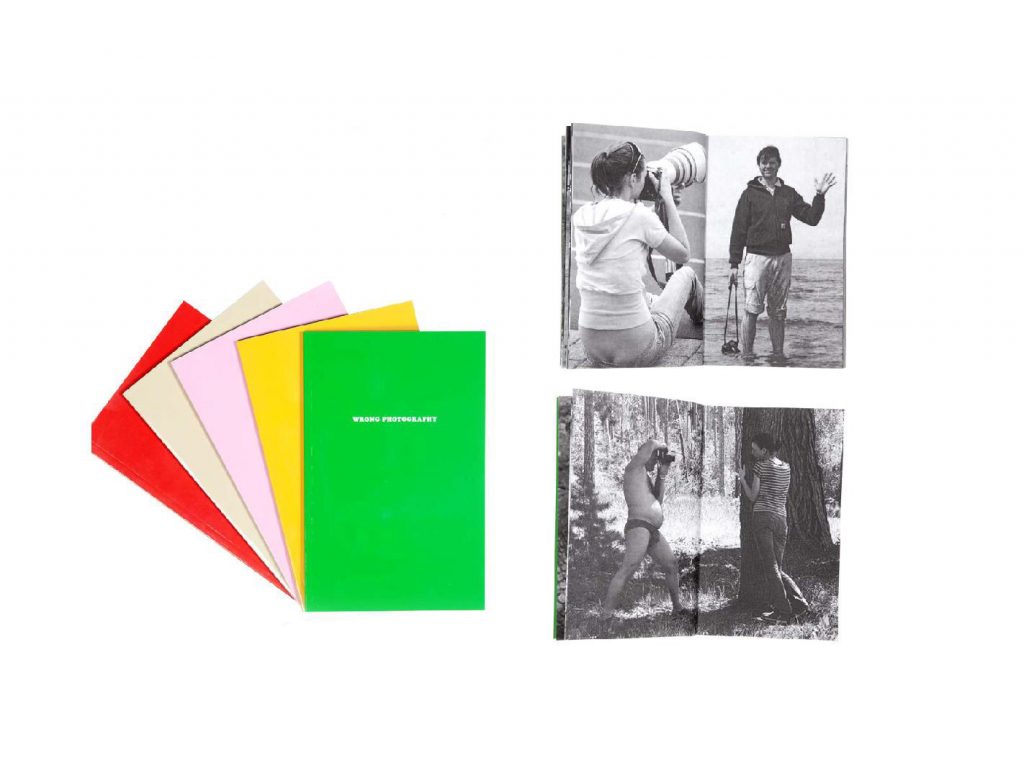

Limited editions of publications consisting of photographs found or inspired by the aesthetics of excess are compiled on the basis of the typology principle. In its multiplicity, they become a testimony of contemporary visual language, typologies of the absurd in everyday life, a record of our ideas of the functions of photography and an imaginary recipient. Entering the world of the Fun archive we assume the role of an anthropologist conducting research of primitive tribes. Comic situations multiply and are put together in the form of artefacts to become an atlas of absurd gestures and peculiar objects. They undermine the sense of creating classifications and taxonomies. They present another side of the Western European, strictly cultural, experience which is reflected by the Mnemosyne Atlas.

Wrong Photography

Thomas Mailaender also attempts to take a close look at wandering motifs, which are, according to Warburg: expressive values through created images (Warburg, Aby, Introduction, p 110). These procedures have the character embark upon a scientific search for knowledge with the use of non-scientific methods. An exteremely straightforward example of Warburg’s Nachleben is a work entitled Illustrated People. The book is a set of photographs created during a residency undertaken in the independent London-based publishing house AMC (Archive of Modern Conflict). The artist, using the mechanism of tanning, exposed and developed photographs on the skin of his models. The images are imprinted upon our memories, and at the same time upon our bodies — “We were imagining a reality in which these images would appear literally on your skin — where there are so many pictures in your life they start to literally come out”.

Illustrated People

In this context, it is worth going back to what is currently happening to the Mnemosyne Atlas on the Internet. Despite the fact that Warburg’s opus magnum, a grand-scale experiment, became an inspiration to a great number of scholars and artists, it is not subject to the processess which it initiated in the hands of its experts. The Warburg Institute at the University of London presents the panels in a systematc way, proposing the viewing paths with accompanying comments. On the Insitute’s Website we read:

The panels of the Mnemosyne Atlas have become yet another object of historical and artistic discourse, with their power originating from the madness of uncontrollable imagination rapidly becoming verbalised. It seems that the impacts of these images will never cease.

Written by Katarzyna Zolich, Katarzyna Ewa Legendź

Aby Warburg, Mnemosyne Atlas

Dina Kelberman, I’m Google