Wro Biennale 2019

The first international WRO Media Art Biennale was held in 1989. Initially, it was just a festival of music-related events (Sound Basis Visual Art Festival), but later the format changed and the festival turned into a new media art biennial. This year, Wro Biennale celebrates the 30th Anniversary. On this occasion we met with Viola Krajewska and Piotr Krajewskim – the founders of WRO. We talk on how the notion of new media art has changed over the last 30 years, based on the history of one of the most important and the oldest biennials of new media in Central Europe.

CL: In 1989 was a very special time in this region of Europe, a period of the stupendous political transition, of hope and anxiety. How did art (including new media art) respond to those political and social changes? How did you manage to establish an institution from scratch without having any native model to follow? Or was there perhaps an institution that you imitated?

VK: We are an NGO, so we don’t copy models, but come up with our own ones. We were graduates of Poland’s first culturology degree course, a pioneering programme which rubbed the authorities the wrong way. That Dr. Stanisław Pietraszko, a scholar and a humanist, had eventually managed to start this program at the University which was still named after Bierut showed that, if consistent, you could succeed with any kind of project. In art, in social practice, in research. The fewer models, the better.

CL: You show Polish new media art against the backdrop of developments in media art in Europe and worldwide. How does Polish art do in comparison? Would you say it was somewhat behind the times, lagging behind technologically in the 1990s? And how has it been changing?

PK: Since the very beginning, this amplitude of art – between high and low technology – has been the very texture of the Biennale, and with fascinating outcomes, too. Of course, the first Animation Workshop was a real sensation, as was the Octan computer borrowed from the air forces for Jaron Lanier, the inventor of the notion and devices of “Virtual Reality,” to play his concert using virtual instruments. But in terms of perception and creativity, both the audience and the artists had an enormous potential for experimentation in the 1990s. That’s genius loci of Wrocław for you, and perhaps also of the Elwro-made Odra computer (which is now blinking to us from the technological afterworld). Don’t forget that the first group in the world to use the GameBoy console for live animations and sound at concerts came from Lower Silesia, too. But, seriously speaking, after the first informational period, when we had showed everything that should be showed of international art (from the monumental presentations and exhibitions of the Chicago Video Data, to Montevideo Amsterdam, to the video collections of the Centre Pompidou and the MOMA), we devoted no less than two special editions to the immensely interesting developments in Polish art. Hence two festivals called the Polish Monitor, which were staged in between the international festivals. In this way, for a few years the biennale took place every year!

Wro Biennale 2019 , opening event, photo: Wojciech Chrubasik

Wro Biennale 2019, Shun Owada, Unearth / Paleo Pacific, instalation

CL: Over all these years you’ve faced the problem of archiving new media art. We are one of the first generations to store all the important documents in clouds, read online newspapers, and have all the contacts on the Internet. Unfortunately, the traditional institutions such as libraries, archives, and museums are only now beginning to notice the expediency of preserving texts and works with no material vehicles. How do you go about that? Do you think it’ll be an urgent problem in the future?

VK: The problem has always been there; some of new media art actually resulted from it; take for example videos registering fleeting performances that evolved into a separate genre of video-performance. At the Biennale, we are going to show the Burial Mound – a collaborative project of the WRO and the Japanese YCAM, dwelling on the problem of passing, disappearing media. Floppy disks with no readers to decipher them, demo-scenes that can no longer be played, the first Polish interactive web performance of which only photos have remained. Thankfully, most of our activities have been recorded. Hence our publication series Widok – recently we’ve produced and published two books about the history of video installations and interactive installations (printed and online), in which we revisit old works and include their documentations. We digitalize our resources and materials, and make them available within our Active Art Archive project, with the Media Reading Room as its part.

Wro Biennale 2019, Space-Moere Project by ARTSAT x SIAF Lab /Akihiro Kubota, Katsuya Ishida, Daisuke Funato, Norimichi Hirakawa, Kei Komachiya,

CL: Is new media art gendered? Stereotypically, new media art tends to be attributed to male activities while in fact outstanding artworks by women are plentiful. When developing your shows, did you pay attention to “gender quotas,” did you look for forgotten female media artists, did you come across groundbreaking works by women?

VK: We did such an experiment once, at one of the early WRO Biennales, staging in parallel two video shows one by women only and the other exclusively by men, without underlining this in any pointed way. Interestingly, the audience definitely (and inadvertently, too) chose the female show.

CL: Over so many years of working and organizing the WRO Biennale, you must have seen thousands of artworks. If you were to choose one or two that impressed you most and should be – in your view – recorded in the annals of history, which one/s would you pick?

PK: There’re so many glittering memories – precious Polish premieres and first showings ever of both Polish and international art; plenty of unique artistic actions; prototypes; improvised exhibitions, often in very untypical art venues. We are working on a special jubilee artbook devoted to them; it’s supposed to be entitled Rezonans (Resonance).

Wro Biennale 2019, PredictiveArtBot.com, Nicolas Maigret (FR), Maria Roszkowska (PL) & Jerome Saint-Clair,

CL: The last question, what can we see during this year edition of Biennale?

PK: The Biennale exhibitions and shows (over one hundred artworks, objects, actions and screenings from Poland and abroad) held at twelve venues – from the National Museum in Wrocław, to multiple Wrocław galleries and the National Forum of Music, to entirely novel art venues (e.g., the Grotowski Performative Art Center at the refurbished Old Bakery) – spin a narrative about the complexity of modern relationships between humans and technology. They explore a shift towards the human as an initiator, a recipient, and sometimes a victim of these transformations. The tale begins from the first Polish robot, a pioneering cybernetic kinetic sculpture by Edward Ihnatowicz, made in the 1960s and recently spectacularly reconstructed after having been found in a field in the Netherlands by means of satellite imaging, a fascinating story in and of itself. The tree I’ve mentioned is EDEN, an action project of Olga Kisseleva (developed by the WRO Art Center in collaboration with the Sorbonne) revolving around a huge plane-tree placed in the National Museum’s Four Domes Pavilion for the time of the exhibition – we fathom the possibilities of a new kind of an organic network in the vegetal world for communicating not only within one species, but also with insects and other animals. French artist Chloé Galibert-Laîné and American Kevin B. Lee correspond with each other, sending each other their computer screenshots as subsequent steps and discoveries in their investigations. She is tracing an ISIS soldier, he – a journalist abducted by the Islamic state. The project reveals how many traces each and every one of us leaves behind on the Internet, and how much information about us ends up there, often without our knowledge and/or consent. To finish with, a few words are due to Kissing Data – E.E.G. KISS. The Dutch artists Karen Lancel and Hermen Maat ask “And how does your brain kiss?” It’s an exceptionally positive project which offers a space for visualizing the human brainwaves while kissing.

Edited by Lisa Barham

Wro Biennale 2019 , Tachihokoru, HOKORI Computing /Katsuki Nogami, Hanna Saito, Ritsuko Miyake, Tatsuya Ishikawa, Kazuya Horibe/

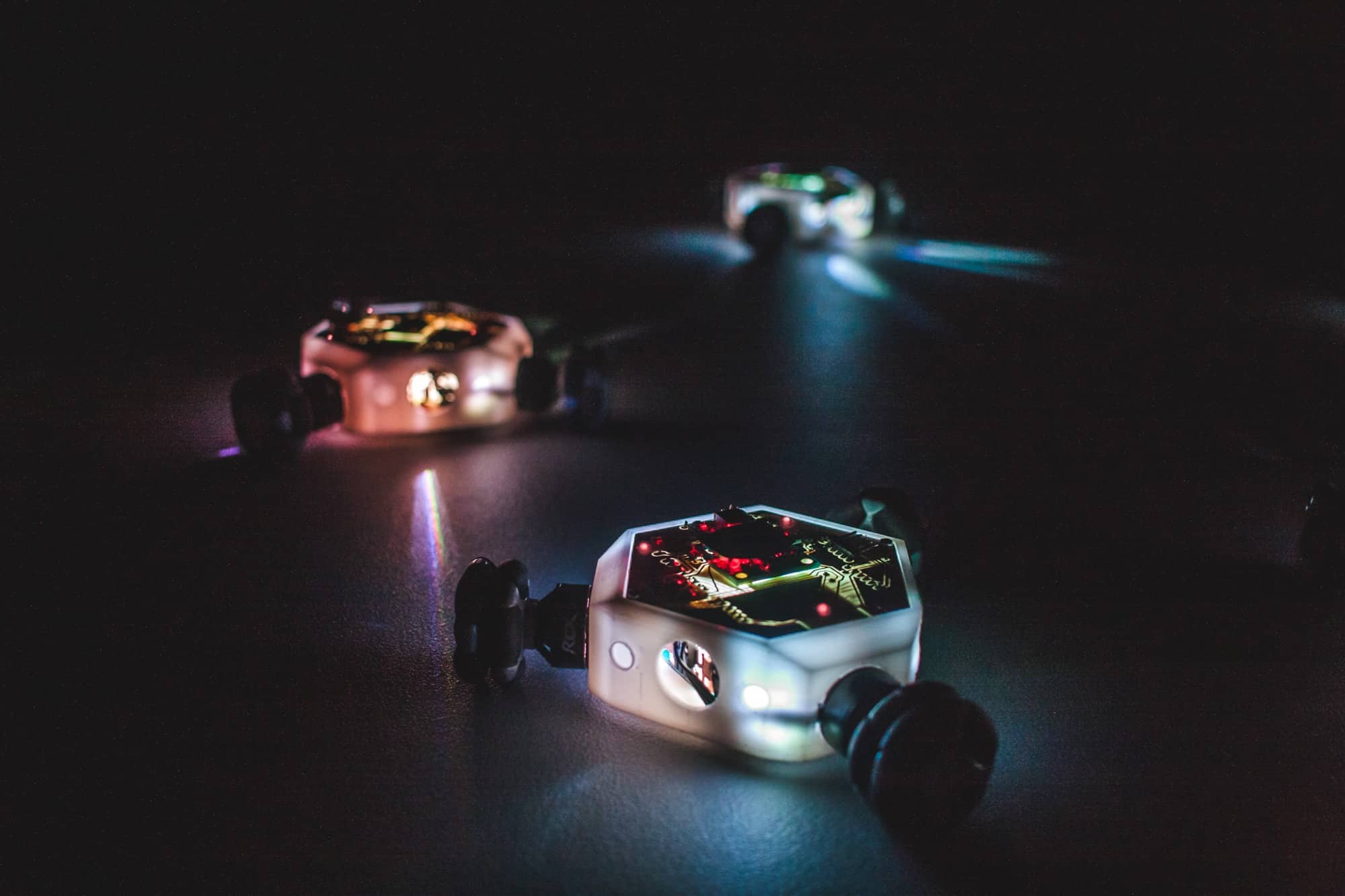

Empathy Swarm, Katrin Hochschuh and Adam Donovan, photo Wojtek Chrubasik

Wro Biennale 2019, New Message, Anna Kaczkowska, Tomasz W. Miśtura, Elżbieta Kowalska, Anna Rogóż, Ewelina Lesik, Piotr Brożek

Wro Biennale 2019, Oswajanie bezdomnego, Magdalena Kieszniewska, photo: Natalia Kabanow

Wro Biennale 2019, Empathy Swarm, Katrin Hochschuh and Adam Donovan, photo Wojtek Chrubasik