Mateusz Kula, Excavations, Ujazdowski Castle Centre for Contemporary Art, photo by Bartosz Górka

Michalina Sablik: At the beginning of our conversation, I would like to congratulate you for winning this year’s edition of Bank Pekao Project Room competition (organised in cooperation with the Ujazdowski Castle Centre for Contemporary Art in Warsaw). The international jury selected your site-specific installation entitled ‘Wykopaliska’ (‘Excavations’) as the best of those submitted for the competition. Why did you choose such title for your installation? Does it have anything in common with archaeology?

Mateusz Kula: The title reflects the way I worked. When I started to split cliparts into basic elements (cliparts are vector graphics, so they consist of numerous small abstract forms) I arranged them in a way investigators and archaeologists do when they try to make sense of objects found on site. They lay them down one next to the other, they often arrange them by shape, size or position in the structure they originally belonged to. And that is similar to what I did. I once learned the methodology of investigating sites of crimes. Regarding criminology, such methodology can be divided into two methods – from the inside to the outside and from the outside to the inside. It is always about going in a circle. What comes further is securing organic and inorganic traces, etc. My working methods were similar, but probably I did more inside to the outside work and then the other way around.

Mateusz Kula, Excavations, Ujazdowski Castle Centre for Contemporary Art, photo by Bartosz Górka

I derived cliparts from my memories and my personal experiences. This phenomenon was connected with the digital revolution which began in the 90s and coincided with the transformation of the political system in Poland. At that time my mum, who was a graduate of Krakow Academy of Fine Arts, used to work in a company which specialised in producing counterfeit jeans pants. Her task was to reproduce the original labels, buttons, inscriptions, etc. as accurately as possible. Generally speaking, she had to copy the whole typography and graphic elements that went into these products. This was the time when a computer came to our house and I became the ‘leading expert’ in operating this device. So, naturally, I also became my mother’s right hand for graphics. Later on there came time for CorelDRAW 3.0 – equipped with a set of ready-made pictures, font types and motives. For us, it was a real marvel which made our work so much more efficient. Around 2007 I began working on my memories regarding this invention. I found the clipart catalogue and, as I travelled within the area, I started to notice the exact shapes which I saw in this catalogue. Virtually everywhere in the Central and Eastern Europe butcher’s banners showed the Pigi pig. Hairdressers in Slovakia, Czech Republic, Hungary and Poland proudly displayed their signboards with Marylin Monroe and James Dean, no matter that they were identical as in hundreds of other businesses of this kind.

But let’s talk a little bit more about archaeology. The title of my project suggests that it was about digging the world out, not only when it comes to the visual aspect of the work. I wanted to help others ‘rediscover the world’ which fades away to a certain extent. The exhibition ‘Excavations’ at the Centre for Contemporary Art primarily focused on cliparts, however, for a long time I have been interested in what happened in the 1990s. In my opinion, nowadays we witness something that I would describe as ‘antiquarian fever’. It manifests itself as nostalgia for the times when there was no digital technology. Today more and more niche products become available, which are variations on themes of these times. Capitalism, which often mixes phenomena from different time periods, willingly recreates the 1990s.

M.S.: Political transformation, the 1990s, the new government and economic system, the creation of new enterprises or, so-called, ‘Poland B’ are the topics of many of your works. In your opinion, what is the connection between aesthetics and politics? Is this issue important for you at all?

M.K.: It sure is. If we work within the field of art, there is a great chance that what we are working with will never become part of politics. I am indeed not a proponent of socially engaged art. For me, art is a sphere where we can discuss dark, uncomfortable topics and taboos. It should not become a vehicle used for simply manifesting or showing something off. Nonetheless, I know there are moments when it should as well become a tool for manifestation.

Mateusz Kula, visual recpie for performance „Thomas Bernhard Day”

M.S.: Is it possible to learn something about a political system of a given place or at a given point in time through aesthetics?

M.K.: Aesthetics would certainly help us draw general conclusions regarding politics. If you read ‘Mass Psychology of Fascism’ by Wilhelm Reich, you know that to understand social attitudes, which are not yet visibly manifested, but which are shared by a significant proportion of a given society, you have to examine visual works, aesthetic choices and sensual manifestations closely. Such examination combines sociology and art and, in my opinion, it allows us to describe political situation very accurately.

Mateusz Kula, Paper puppets for shadow opera based on „Verstörung” novel by Thomas Bernhard

M.S.: So, what are your conclusions about the 1990s?

M.K.: There was certainly an enormous amount of positive energy after the communist system was dismantled. It was virtually like colours and shapes extravaganza. It was about this moment ‘right after’. I remember the scene that Łukasz Orbitowski described in his book. The protagonist is having a bath and suddenly he realises that he does not have to use grey soap anymore because he has a plethora of colourful vials filled with scented cosmetics available within arm’s reach. This is precisely the moment right after the socialist system with all its greyness went away. Obviously, kitsch was an inherent part of these times. There was an enormous amount of energy which exploded just as the old political and economic systems did. Their demise pushed forward numerous changes in the public space and visual sphere. These changes were vibrant and organic at the same time. For me, an important aspect of the new visual layout of the public space was an increase in the amount of trees in the streets and in tenement house courtyards. There were also new forms of printed materials which blended into this space perfectly. Poland of the 1990s was a somehow strange place with its old monuments, tenement houses, colourful shapes and hedges which grew in every courtyard, taking up space in an uncontrollable way. This was a genuinely demonic period… the period of transformation.

M.S.: Is this why the shapes of cliparts that you use in your works are so organic? Is this why you present seashells, tiny stones, sticks, etc.?

M.K.: Indeed. When I worked on my installation at the Centre for Contemporary Art, I constantly visualised those colourful, shabby courtyards at the back of small businesses, shops, etc.

M.S.: What methods do you use in the creative process? Are you a collector, an idea picker, a discoverer of artefacts or someone else?

M.K.: It would be too difficult to use one name for my creative method. I would rather describe it as follows: I often make choices for the reasons which remain totally vague for me. These choices refer for example to the moment I take a certain picture or to the selection of a certain object or a memory. I collect everything I picked on such occasions and save it for later. Afterwards, I let my imagination search for references. After a year or two everything simply falls into place and the things I collected combine into a coherent whole. They start to form meaningful constellations which I am finally able to name and define. I am not fortunate enough to have my own storage space, where I could keep all that I collected. Therefore, I often only gather documentation, photographs or sketches. I also frequently use fiction creation methods since the objects of my interest are often entire buildings. If this is the case, I describe them for documentation purposes. Later on, such objects become a starting point for entirely new scenarios. So, generally speaking, what I do is gathering certain objects, pieces of narration or whole scenarios which I subsequently edit. This creative process never ends.

Mateusz Kula, Excavations, Ujazdowski Castle Centre for Contemporary Art, photo by Bartosz Górka

M.S.: Another motif present in your numerous works is a collection and the act of collecting. In the commentary to your ‘Excavations’ installation you mentioned Aby Warburg and his unfinished ‘Mnemosyne’. I have an impression that this particular art historian and his work are a crucial point of reference for you. Is there something that your activities and his activities have in common?

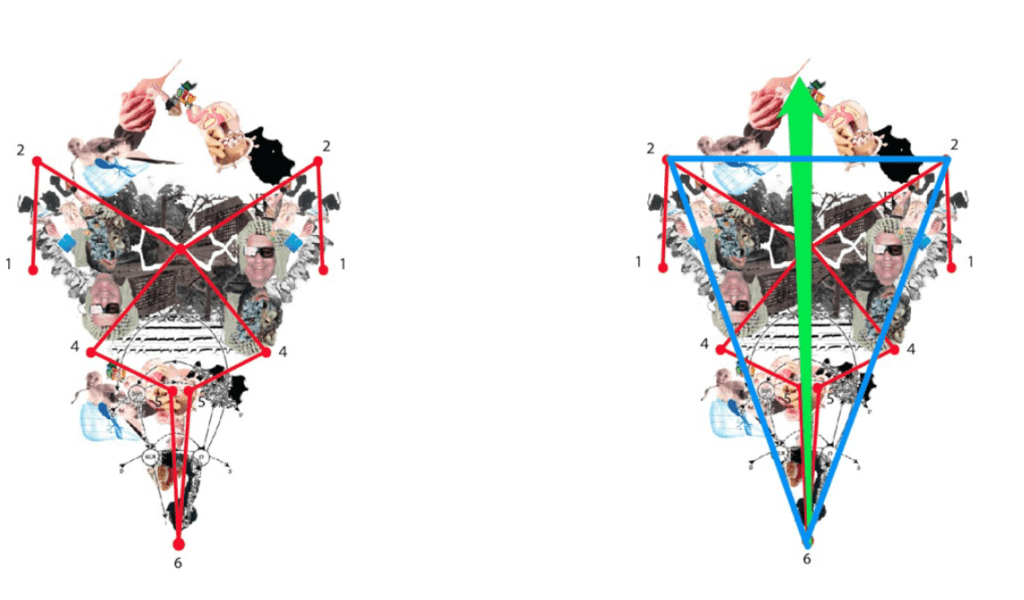

M.K.: Aby Warburg is a creator of iconography and this is why he is so important for me. He studied dynamics between pictures which seemingly did not have anything in common. I try to adopt a similar attitude when I work on my own collection. At the early beginnings of my efforts to create a specific project I use iconographic charts and I try to combine and contrast pictures which represent certain realities and traditions as a whole or depict specific ideas. For almost every single project, I create a series of collages which are combinations of matching iconographic representations. I also have to stress the importance of memories. I very often use over again the motives I forgot some time before. I remind myself of such motives incidentally, thanks to seeing certain colours, shapes or after an unexpected meeting with a given person in the street. These forgotten motives are usually a sheer pleasure to work with. They are similar to actions done by mistake or to surprises I prepare for myself. I forget about something and, suddenly, I recall it. It is like finding a forgotten banknote in the pocket of your jacket. If I am able to define a relationship between two pictures, I prepare a collage. This is a part of my work I usually do not present to wider public.

M.S.: When it comes to academics, you started by studying philosophy. You are also interested in classification and systematics. Do these fields of study influence your work as an artist?

M.K.: I am of the opinion, that the work of a philosopher has a lot in common with the work of an artist and that these types of activity complement one another. The primary difference, however, is the material which representatives of both professions use for creation. Philosophers work with ideas and language, but in a totally different way than writers do. Artists, on the other hand, work on sensory impressions and stimuli.

I started my career in visual arts, because of my parents who were both graduates of the Academy of Fine Arts. Thanks to them, I was exposed to art from an early age. I also enjoyed drawing for as long as I can remember. Later on, I grew interested in IT, programming and computers. From there I quite quickly got to philosophy and system building. I also became a fan of fantasy. From philosophy I came back to art. I presume that philosophers find themselves somewhere in between discovery and creation, just as artists do. Most importantly, philosophy allows humans to understand what is happening here and now. Art offers similar possibilities of understanding, but on a sensory level. Even if people do not gain this understanding thanks to their encounters with philosophy and art, they at least are offered important opportunity.

M.S.: Your works perfectly visualise problems which would normally be subject to extensive descriptions and philosophical or sociological analyses. I think that, when it comes to art, it is important to differentiate between visualisation and narration.

M.K.: I do not quite agree with you. Visualisation aims are to present ideas, which could be described by using abstract language. Art is about sensory impressions. Artists discover things which would never be found by philosophers. Although art and philosophy use similar methods, they are totally different in terms of material used.

M.S.: So, artworks with ideas which cannot be described with words, is that right?

M.K.: They can be described verbally at some point because they are converted into a work of art. I think the fact that works of art allow to present, what people are unable to name or describe is an important political aspect of art itself. The underlying ideas are describable only after they are processed and assume a given form. They cannot be described as such until they solidify as a work of art. Time is indispensable here. One is not able to analyse these ideas in real time.

Mateusz Kula, Untitled from series „Middle Ages Of Teenage Empire”

For a long time ‘hortus conclusus’ was particularly important for me. Wild nature which is growing and expanding can be described only after being separated by a wall from the space which we control, i.e. a garden. This separation postulated by Kant was a key issue for me. I have to admit that it is problematic for me to refer to the old substantialist categories propagated by the so-called, object-oriented ontology. There are also ‘Democracy of Objects’ initiatives and the new materialism which strive for a revival of pre-modern notions. For me it is a contemporary version of vitalism and spiritism from the early 20th century.

M.S.: You are an interdisciplinary and intermedia artist and you always act in between different fields. How do you choose techniques and media for your works?

M.K.: I particularly like sketches and iconographic charts, but this is more about methods. What really impacts the final result is a medium I used. I am going to work on a documentary movie for a year, although I never did this before. I also work a lot with texts, I make sketches, I work with spatial forms and all of these activities complement one another. I tend to regret that, I am not an artist working with one specific medium. I look at my colleagues who are painters and who come to their studios every day and I feel jealous. Being organised and consistent while working is a tempting prospect for me. A painter comes to a studio every day and resumes working on something which he left unfinished on the previous day. There is something similar to this in the way I work, but my activities ask for more perseverance. Although, I never painted myself, the methods and techniques used by painters are important for me. I try to use the same techniques, the only difference is that, I work with different media and that my workshop is moving from one place to another.

Mateusz Kula, Ebenhoh, paper puppet for shadow opera basen od „Verstörung” novel by Thomas Bernhard

M.S.: You recently finished your studies in Vienna and you became a graduate of Art and Science programme at the University of Applied Arts. This is an unconventional field of study. Tell us what the programme like was and what interesting activities it included.

M.K.: Art and Science programme in Vienna required all students to choose institutional partners who were somehow related to art. I cooperated with Radiology Department of the City Hospital in Vienna and with the Institute of Wild Nature. During each semester we needed to cooperate with our partners and meet the employees to work on certain ideas together. The results of such efforts were often useful for the field of art, but usually had no significance for science as such. They were not strictly about science. Some students benefited from the technical opportunities offered by their partners and prepared works in which they used the latest technology, e.g. X-ray machines or CAT scanners. I approached cooperation with my partners more symbolically. I was more interested in their structure and related stories.

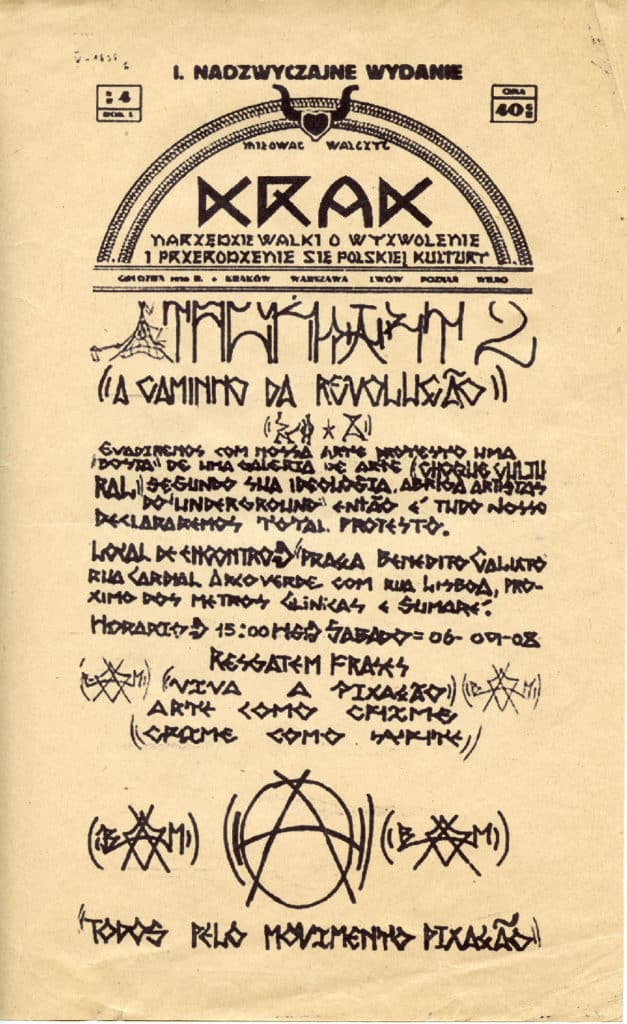

The Institute of Wild Nature and the City Hospital represent two realities which are crucial in the German-speaking countries (especially in Austria), namely the world of medicine and the world of wild nature, both inherent to the modern world. These two worlds are perfectly described in one of Thomas Bernhard earliest novels entitled ‘Gargoyles’. I worked on this novel throughout the course of my studies. I tried to create an opera based on ‘Gargoyles’. It was supposed to be staged in the hallway of the City Hospital. Unfortunately, due to administrative obstacles, my project could not have been realised. “Gargoyles” is a novel which tells the story of a doctor working in the countryside. He visits numerous terminally ill patients accompanied with his son. On their way they have to walk through the dark forest (Deutscherwald). If we tried to visualize their route it would be a way being rubbed out on a sheet of paper covered with tightly tangled lines. The culture of the German speaking countries very often uses the motives of wild nature, German forest and cold science, as well as their close interconnectedness. The belief in natural order is constantly being contrasted with pagan mythology and beliefs in substantialist nature of flora and fauna. Not much has changed there until the present day. Maybe nothing has changed at all. The inhabitants of Vienna still love forester costumes and völkisch heimat.

Mateusz Kula, Untitles from series „Middle Ages Of Teenage Empire”

M.S.: To sum up, could you tell us what do science, philosophy and art have in common?

M.K.: I would not be too original and I will quote Alan Badiou. If we added love to the three spheres you mentioned, we would have a list of the four spheres within which something can happen and change is possible. This can even be a revolution aimed to upturn the present system. In this respect, I fully agree with Alan Badiou, who is a phenomenon in the history of philosophy.

Mateusz Kula, Excavations, Ujazdowski Castle Centre for Contemporary Art, photo by Bartosz Górka