Christopher Williams, Angola to Vietnam*, 1989. Collection Stedelijk Museum Amsterdam, donation Thomas Borgmann, Berlin. (Installation Stedelijk Museum November 2017. Photo: Gert Jan van Rooij)

The Success

Until March 4, 2018 the Stedelijk Museum in Amsterdam hosts the Jump into the Future exhibition that occupies an entire first-floor of the Museumplein building. An abundance of contemporary artworks on display, which originate mainly from the 1990s and 2000s, was donated to the museum by Thomas Borgmann, the German art collector. Undoubtedly, the presentation will go down in history for several reasons. First of all, the offering is the second largest donation the Stedelijk Museum has ever received. In the years 2016-2018, Borgmann added 217 works of art encompassing 647 objects. However, Beatrix Ruf, an artistic director, ultimately resigned amid major controversy sparked off by the gift.

Wolfgang Tillmans, Lucy McKenzie, installation view Jump into the Future – Art from the 90’s and 2000’s. The Borgmann Donation. Photo: Gert Jan van Rooij

The Collector

In the age of 16, Thomas Borgmann (born 1942) already knew he was going to become a member of the art world. After two semesters, he dropped out of college in Hamburg, where he studied art history. The curriculum, which came to a halt around 1850, fell short of his expectations. In 1964, he was hired as an assistant and secretary of Rudolf Zwirner, a gallery owner and a distant relative of his, and thus shaped the art scene in Cologne. He opened Andy Warhol’s solo show entitled Most Wanted (the Rudolf Zwirner Gallery, 1967) amid a general lack of interest in pop-art among art collectors of that time. Borgmann excelled in scouting undiscovered yet talented artists. For instance, he intended to purchase the Milan Cathedral painting by the regular student named Gerard Richter. Ultimately, the transaction wasn’t completed due to Borgmann’s payment being substantially lower than the painting’s price, which amounted to 1200 DM. In 2002, the painting was sold by Sotheby’s for almost 2,5 million dollars.

Borgmann collected and exhibited the epitomes of modernism. In 1967, he moved to New York and started working as an assistant in Allan Frumkin’s gallery. He spent his days working and building his own art collection. After her deceased grandmother, Borgmann’s wife inherited some money which collector decided to to invest in the purchase of works of art by such prominent artists as Balthus, Cy Twombly and Vasarely. Nonetheless, the following year he returned to Cologne to launch the Thomas Borgmann Gallery (1969) in his own apartment. During the day, he sold and showcased art in the rooms, in which he came to bed at night. He stayed in business until 1985. In the years 1993-1994, he run the Borgmann Capitain gallery in collaboration with Gisela Capitain.

Matt Mullican, Subject Driven, 1978-2008. Collection Stedelijk Museum Amsterdam, acquisition Thomas Borgmann, Berlin. (Installation Stedelijk Museum November 2017. Photo: Gert Jan van Rooij)

Jump into the Future

Thomas Borgmann, a novice art collector and gallery owner, came to Amsterdam for the very first time in the late 1960s. In the interview published in the exhibition catalogue, he takes a retrospective nostalgic look at his visits to the Stedelijk Museum that, in his opinion, was the head and shoulders above the rest regarding their collection of avant-garde works of art by for instance Picasso, Mondrian and Lichtenstein. You didn’t have to cross the Ocean to admire contemporary pieces by the American artists. Borgmann viewed his visits to the Stedelijk in the 1960s as the eponymous “jump into the future.” The phrase lays an emphasis on the collector’s close relation to the museum, as well as the intrinsic nature of collecting works by emerging artists whose careers are yet to unfold. Collecting is a gamble. You take a shot in the dark that shapes young people’s entire future.

Jutta Koether, installation view Jump into the Future – Art from the 90’s and 2000’s. The Borgmann Donation. Photo: Gert Jan van Rooij

Starting Again and Again

When asked about his collecting style, Thomas Borgmann retorted: “I build things up in order to be able to change my mind again.” What it actually means in practice is observing global trends and purchasing works corresponding to those trends only to put some of them up for sale when the paradigm and art world’s fascinations shift, so that one can build another subcollection reflecting another tendency. In the collecting jargon, the style is dubbed “serial infatuation.” Apparently, the German collector was indeed infatuated with the new generation of artists from Cologne, London and New York that emerged in the 1990s, since his donation to the Stedelijk museum encompasses chiefly the pieces produced in this period, which were also included in the Jump into the Future exhibit.

Enrico David, Bulbous Marauder, 2008. Collection Stedelijk Museum Amsterdam, donation Thomas Borgmann, Berlijn. (Installation Stedelijk Museum November 2017. Photo: Gert Jan van Rooij)

Art from the 1990s and 2000s

The exhibition features artworks by Cosima von Bonin, Matt Mullican, Lucy McKenzie, Jutta Koether, Paulina Ołowska, Wolfgang Tillmans, Christopher Williams, Cerith Wyn Evans and Heimo Zobernig. The exhibition was designed to present works of certain artists in separate venues. The reasons are twofold, at least. To begin with, the design was dictated by the nature of the works consisting largely of art installations, whose origins could be traced back to Duchamps’ ready-mades. Installation art, which has gained ground in the late twentieth century, finally came to the fore in the 1990s and 2000s. It was a time of blurring boundaries in the arts. The focus shifted from the individual object to the spatial presentation of multiple works. This pivotal decade was marked by the diversity of contemporary art and the lack of dominating tendencies. What is more, the 1990s were typified by various social and political points of turbulence: the fall of the Berlin Wall, the Yugoslav Wars, conflicts in the Middle East and the 9/11 in the US. It was also the epoch of the global digital revolution. Artists became more mobile and were offered opportunities to travel the world. New economies began to blossom and a global art world emerged. A newfound sensitivity to gender diversity and queer identity shaped public debate. Furthermore, the substantial donation managed to direct the Stedelijk Museum’s attention towards most current artistic strategies. Up until that point, the institution’s programme hadn’t necessarily included a wealth of contemporary art shows, with the exception of Wild Walls (1995) and From the Corner of the Eye (1998) exhibitions, as well as, the following artists: Pipilotti Rist, Kai Althoff, Douglas Gordon, Wolfgang Tillmans and Cerith Wyn Evans. In the upcoming years, the museum made amends and opened the shows of such artists like Wolfgang Tillmans, Paulina Ołowska, Cosima von Bonin and Lucy McKenzie. In a way, Borgmann’s gift bridged certain gaps in the museum’s collection of the artworks from the abovementioned decades.

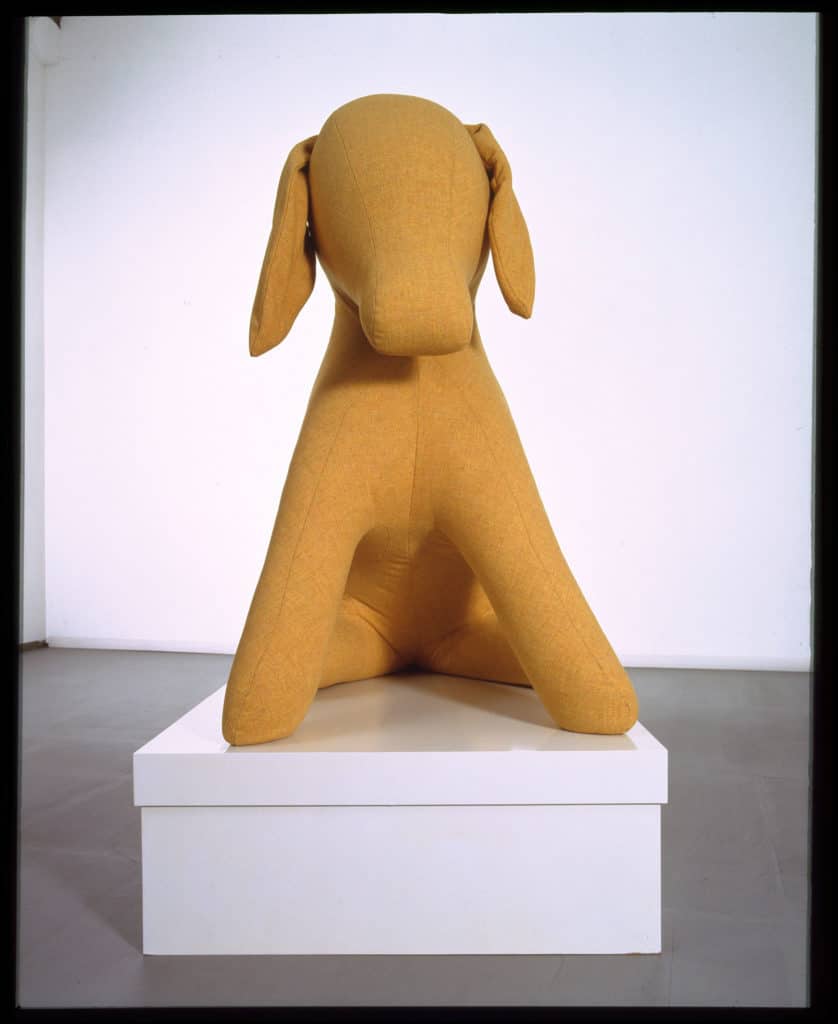

Cosima von Bonin, UNTITLED (THE YELLOW DONKEY WITH BOX), 2004. Mixed media. 148.5 x 81.6 x 142 cm. Photo: Simon Vogel. Collection Stedelijk Museum Amsterdam, donation Thomas Borgmann, Berlin

Art Installations

Monumental art installations on display captivate the viewers, for instance, Kapitulation (2004), by Cosima von Bonin. In order to peak into the enclosed space made of chipboard with no doors or windows, the viewer needs to climb the staircase or look into one of the mirrors hanging above. The interior is filled with a spider web, colourful rolling pin, textile catamaran and chalked comic book – all those components, which derive from the performances entitled 2 Positions at Once and Dog School (2004), are surrounded with large dog sculptures made of cloth reminiscent of children’s toys. The retrospective composition embodies the artist’s oeuvre that could easily be included in tendency called Super-Hybridity. In her art practice, Cosima von Bonin often alludes to the images from art history and pop-culture. A perceptive spectator would certainly notice her references to the series of paintings by Sigmar Polke depicting guard towers, Moujik – the famous dog of Yves Saint Laurent, and Star Wars. The artist’s works have always bordered on homage and parody.

One of the most noteworthy works on the exhibition is Matt Mullican’s mixed-media art installation presented in five galleries, the walls of which are all painted in different colours. The piece incorporates 56 works of art consisting of 305 separate objects created in the years 1970-2008. According to the artist, every single element of the world carries certain meanings. A system of the hierarchy should thus be established among those elements. Colours are of paramount importance to the system because they refer to the specific spheres of life on earth. Green symbolises nature, blue stands for everyday life and objects, yellow denotes art and ideas, black represents language and signs, while red evokes the subconscious.

Paulina Olowska, installation view Jump into the Future – Art from the 90’s and 2000’s. The Borgmann Donation. Photo: Gert Jan van Rooij

The Polish Aspect

Among the pieces donated to the museum were also Paulina Ołowska’s works that were exhibited in the stylised version of a store window in communist Poland. Vibrant pieces of clothes hang on two mannequins near the mirror and fabric roll. In this case, fashion encapsulates the political climate of a given period. Party Kleid, the gouache painting by Paulina Ołowska portraying a hybrid between a suit and a dress, is a fine addition to the presentation. The painting was based upon the cult design by Elsa Schiaparelli, an Italian fashion designer who drew her inspiration from the Surrealists and Dadaists. Schiaparelli was famous for her runway shows. Once, models showcased paintings instead of clothes. Ołowska performed a subversive gesture of presenting clothing on canvas.

It’s worth mentioning that Paulina Ołowska’s works of art had previously been exhibited in the Stedelijk Museum Amsterdam on her solo show entitled Au Bonheur des Dames (2014). Moreover, she had already participated in the Stedelijk Museum CS project, as well as the artist-in-residence programme in the esteemed Rijksakademie (2001-2002).

Cosima von Bonin, installation view Jump into the Future – Art from the 90’s and 2000’s. The Borgmann Donation. Photo: Gert Jan van Rooij

Controversy

In the early October 2017, NRC Handelsblad, the Dutch newspaper, published several investigative reports by Daana van Lent and Arjena Ribbens that called into question the transparency of the Stedelijk Museum’s operations with regard to the Borgmann’s gift. The series of articles uncovered the details of the transaction between the museum and art collector. Why had the artworks’ donation been conditioned on €1,5 million of art purchases? The terms of the agreement stipulated that a prerequisite for Borgmann’s donation was the museum’s acquisition of artworks by Michael Krebber and Matt Mullican, as well as their long-term loan of a number of other pieces. NRC probed into the relationship between the private art collector and Beatrix Ruf, who signed the agreement on behalf of the Stedelijk Museum in Amsterdam. According to the journalistic reports, private art consulting activity of one of the most influential members of the art world- at least according to Art Review’s ranking – might have presented a possible conflict of interest.

Beatrix Ruf, the former chief curator of the Kunsthalle Zurich, was appointed as the artistic director of the Stedelijk Museum in November, 2014. The NRC journalists examined her income statements and raised questions about current matters, the one-woman art consulting company she established, that reported a staggering profit to the tax authorities. In 2015, Ms Ruf declared that her annual income amounted to over €430,000. In the aftermath of the scandal, Beatrix Ruf stepped down voluntarily as the museum director on October 17, 2016. The board decided not to address the issue while the investigation was still pending. Last November, the New York Times published an official statement by Beatrix Ruf who called the scandal “a misunderstanding.” She added that she resigned because she felt the ongoing negative publicity surrounding her side activities was harmful to the museum. Furthermore, she wished to protect the institution from a media furore. The former artistic director of the Stedelijk claimed the funds came mostly from a bonus she received from Michael Ringier, the Swiss publisher and art collector with whom she had collaborated for over twenty years.

Thomas Eggerer, installation view Jump into the Future – Art from the 90’s and 2000’s. The Borgmann Donation. Photo: Gert Jan van Rooij

The article was based on the following source materials: “That was then, but this is now” by Jörg Heiser, “Absentees Return” by Isabelle Graw, and the interview with Thomas Borgmann conducted by Beatrix Ruf and Martijn van Nieuwenhuyzen.

Written by Michał Dawid Sypień

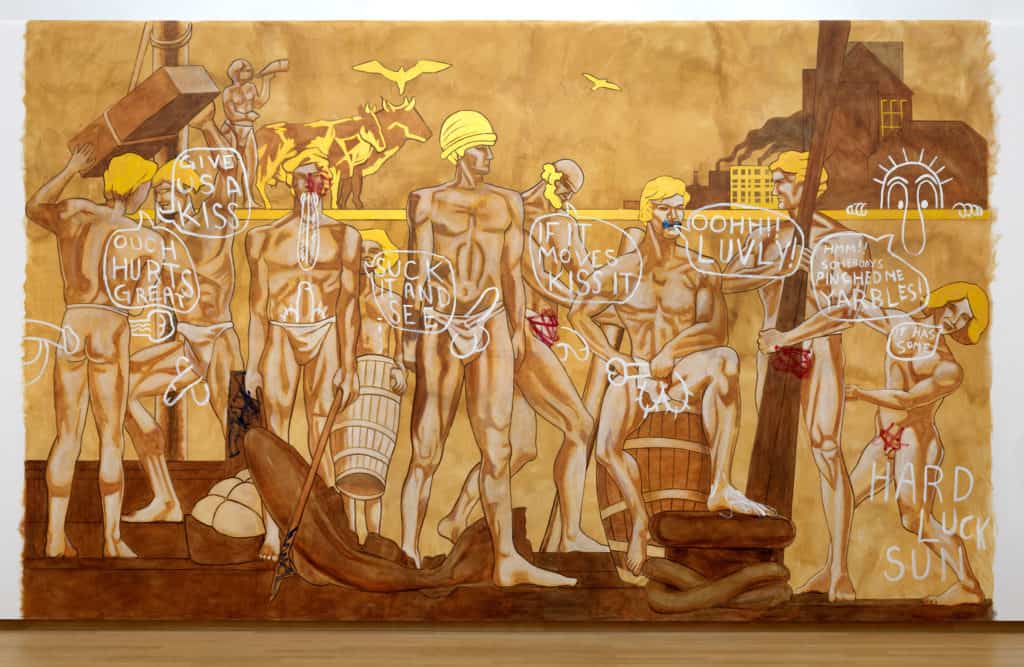

Lucy McKenzie. If it Moves Kiss It II, 2002. Acrylic paint on wall. Collection Stedelijk Museum Amsterdam, donation Thomas Borgmann, Berlin. (Installation Stedelijk Museum November 2017. Photo: Gert Jan van Rooij)

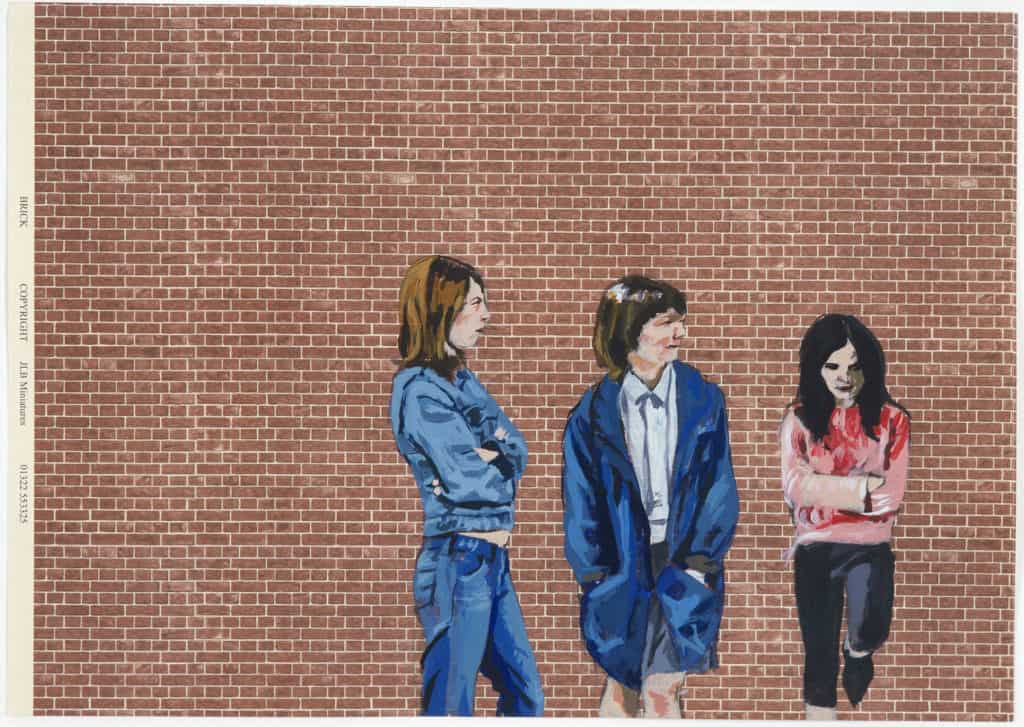

Lucy McKenzie, Untitled (Bi-Curious), 2004. Acrylic on paper. 33.3 x 43.3 x 2.5 cm. © Lucy McKenzie. Collection Stedelijk Museum Amsterdam, donation Thomas Borgmann, Berlin