It is the year 1993 – a conference on feminist art is taking place in Vienna. Maria Pinińska-Bereś is among the participants. She notes down her reflections on the event:

“We were familiarised with the achievements of women in the field of art from the period when their self-awareness was still developing. We learned about the old works which already faded away and noted down names of women who used to be prominent figures in female art. At that moment, I felt a bit strange and started to count. My Tables with parts of the female body as the dish served were shown to the public in 1968, whereas one of the most prominent works of the feminist art movement, Dinner Party by Judy Chicago dates back to 1974-1979!”[1]

Maria Pinińska-Bereś, “Table II – The Feast” (1968)

Works by Maria Pinińska-Bereś (1931-1999) are among the pioneering ones due to many reasons. Her projects were deeply individual, outside of the mainstream and full of irony. They remained detached from the pursuit of artistic greatness and did not aspire to be recognised as flagship representations of the feminist movement. Her art was truly multidimensional, which she managed to achieve thanks to her elaborate personal story. She was born in 1931 as a member of an aristocratic family. Her childhood was a true impersonation of a “golden cage”. Maria lived a life of a happy child, but she did not have a chance to interact with peers. She was mostly surrounded by servants and governesses. Maria’s early years were the times of “pointless existence and elaborate illusions”[2]. Her life was full of tales and stories told by her grandmother who came from Luxembourg. She eagerly watched her beloved father, who was an Uhlan (light cavalry)and who participated in the fight for Polish independence. He was also very talented when it comes to visual arts.[3]

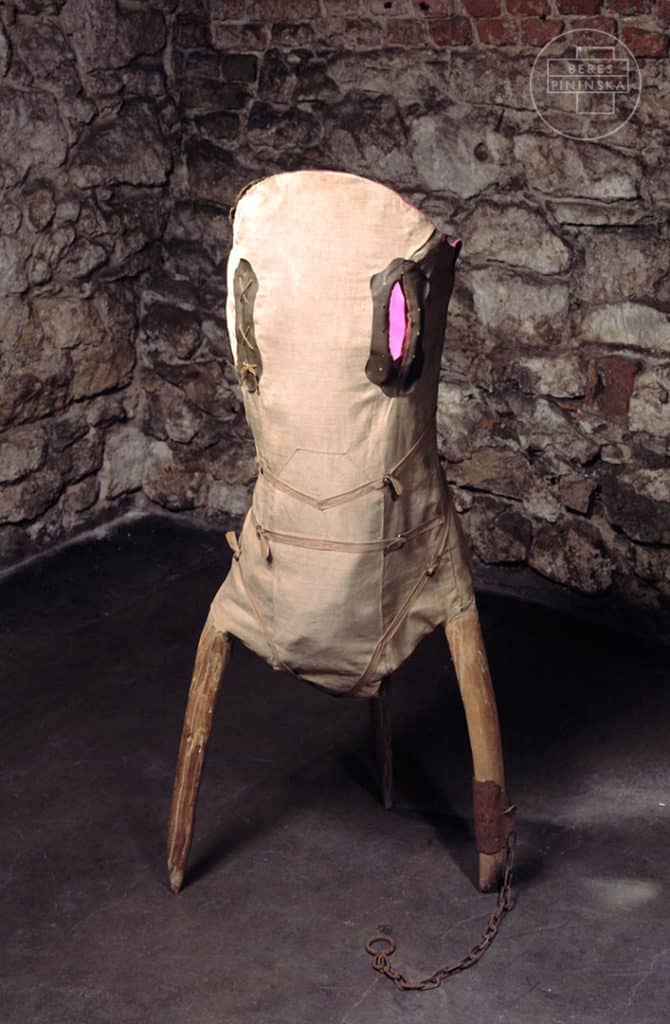

Maria Pinińska-Bereś, “Existentialium of Big β and Small π” (1991)

Everything changed when the war started. Maria’s father was imprisoned by the Russians. “I have been waiting for him and looking for him my whole life”[4] – she wrote. It was only in 1990 when she found out what really happened to him. In fact, her father was murdered by NKVD officers in Kharkiv. There was no consolation for Maria even when the war ended. Since she was the daughter of an officer who was politically active in the pre-war times, she was captivated and sent to the communist camp situated within the area of the former Nazi concentration camp. Maria’s grandfather became the head of the family and she grew up “in a very specific environment which was supervised by a patriarchal senior, whose views on life developed as early as in the 19th century.”[5] The only sphere where she could feel liberated was art, which seemed “a free area with no social conventions, no coercion; a sphere of creative and real projection of one’s personality.”[6]

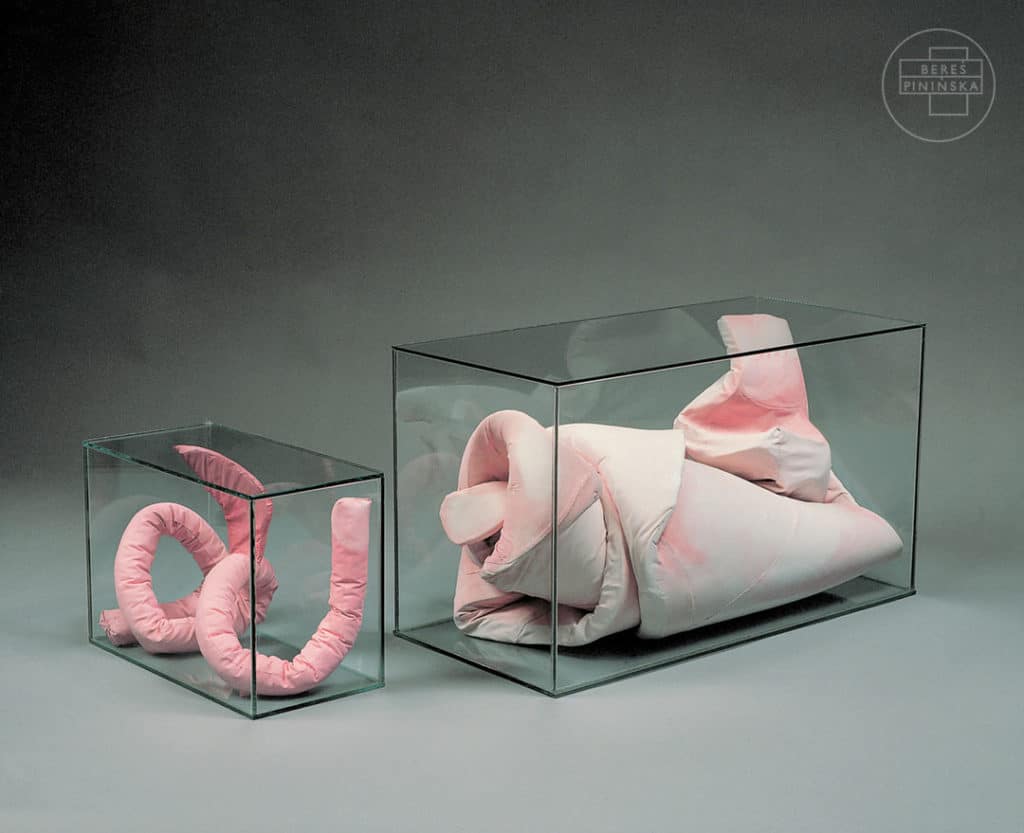

“Love Machine” (1969) and “Screen” (1973) at THE WORLD GOES POP exhibition in Tate Modern (2016)

As we see, the foundations of the artistic activity of Maria Pinińska-Bereś were complex and born out of difficult life experiences. Changes in her activity were always revolutionary rather than evolutionary. The first and probably the crucial breakthrough for Maria came right after she graduated from the Academy of Fine Arts in Krakow. She was an extremely talented student but, shockingly, decided to reject the traditional sculpting methods and techniques, as well as the commonly used materials. She said later on: “I murdered my own talent. Why did I do that? I did not want to remain a part of the chain of traditional sculpting.”[7]

Maria Pinińska-Bereś, “Is a Woman a Human Being?” (1972)

Maria Pinińska-Bereś, “Poetic Place”, 1974

She looked for new means of expression, which resulted not only from the influence of avant-garde paradigm. She depicted the issues and chose the formal means of expression which had something in common with women and which were in line with the views and opinions later called “feminist”. “I rejected what was conventional and, therefore, I had to go deep within myself. And ‘myself’ was a woman with the whole bunch of problems faced by females. I decided to get rid of heaviness in my sculptures. I did it because I have always been dreaming of the day when I would be able to carry my own sculptures alone, without anybody’s help (especially men’s).”[8]

Maria Pinińska-Bereś, “King and Queen” (1986)

In the mid-1960s Maria started to experiment with multi-layer glued paper. At that time, she created a series of Corsets and Covers, i.e. “empty shells which, more or less, resemble clothes.”[9] Corsets were “a manifestation of social conventions imposed on women and shaping them in line with the requirements of patriarchal society. They used to form both bodies and minds.”[10] However, Maria quickly stopped working on this series and she focused on new and less literal fields of art. Even though her focus changed, she retained the results of her earlier efforts and her discoveries. Then came the mini-series of Tables in which she analysed how women start to be treated as artefacts and consumption goods. Afterwards, the artist created a very important Psychofurniture series. Maria’s works created in the 1970s were much different from the earlier ones, which remained quite simple and stark in appearance. Works from the 1970s were “almost impeccable, both in terms of their perfection and beauty.”[11] It was the time when Maria introduced two most characteristic elements of her works – the softness and the mixture of pink and white colours. The form was no longer closely resembling a human body and the shapes sewn of pink fabric, which was later stuffed and modelled were more abstract starting from this point in time. At the beginning, cotton wool served as stuffing. However, it was replaced with polyurethane foam as early as in mid-seventies. Thanks to this new material, Maria’s figures gained new meanings and the overall impression they created became totally different. Maria relied on resilience and bounciness of polyurethane foam sheets. She covered them with canvas cut and sewn in specific shapes and, afterwards, she covered the whole work with acrylic paint. In this highly unconventional way, she created modelled sculptures.

Maria Pinińska-Bereś, performance “Passage Beyond the Quilt” (1979)

Pink was the colour which we can spot even in the earliest works of Maria. However, in the 1970s there was a significant change in the way this colour was utilized by the artist. She started using pink acrylic paint to cover paper shapes. As she wrote: “From now on this particular colour becomes my identification and it will appear along with neutral white.”[12] A few years later, soft elements also started to be covered with acrylic paint, which served as shape retainer as well. We can say that the colour was used for modelling purposes, but also to add meaning to the shapes created. Pink was not only associated with women but, more importantly, with life and gender, was an indication of lasciviousness.

Maria Pinińska-Bereś, “Pink Mirror” (1970)

It is easy to misinterpret the meaning of works by Maria Pinińska-Bereś. One can inadvertently approach them with stereotypes on pink colour, softness, feminism and eroticism in mind. These stereotypes will prevent such person from understanding the full meaning of what he/she actually sees. Maria put the greatest emphasis on “form and the problems associated with it” rather than becoming completely consumed with the content.[13] Tension and friction play an extremely important role in her sculptures, involving both form and the used materials. Other crucial things are the arrangement of elements and proportions. Maria expressed her objection towards the traditionally understood art in yet another way. She resigned from using plinths, which were a mandatory element while exhibiting sculptures in the 1960s. Her numerous works, especially those created in the 1970s and 1980s “play with space and fills galleries.”[14] The key to the correct understanding of Maria’s works is their suitable location within a gallery space. Unfortunately, this issue is often neglected or not given enough attention while exhibiting these works.

Maria Pinińska-Bereś, performance “Laundry II” (1981)

Maria Pinińska-Bereś is often described as a feminist artist and this opinion tends to be not well thought out. This is yet another proof that the artist’s works are interpreted in a superficial manner. The artist herself did not describe her works as feminist. The notion of ‘feminism’ itself was not used in Poland in the 1960s-70s. Maria created her works based on her intuition, experiences and memories. “After all, every work of art which surrounds us referred to the past or to something from the outside world. I was not looking for west catalogues or magazines like many others used to do at that time.”[15] Maria’s discoveries related to femininity and the status of women in the society were the result of her own efforts. She did not even realize that she came ahead of female artists from Western Europe by something like a few years of research and artistic quests. She was disappointed with West European feminism. She got a negative impression already in 1979, when she first saw European feminist art at the international exhibition of female art. The female artists whose works were presented treated art as a mere instrument for propagating their ideology, against which Maria strongly objected. She could not accept using art as a vehicle to spread feminist ideas and this attitude was consistent with her disregard for art serving as a ‘monument’ commemorating certain events or individuals. Maria’s artistic narration was much more complex. Her message involves life in its whole complexity and with all its aspects.

Maria Pinińska-Bereś, “Well of Pink”, 1977

Maria’s attitude towards feminist art was presented in 1980 in a performance entitled “Laundry”. During this performance she washed pieces of fabric with letters printed on. When she hanged all the pieces, one could see that the letters formed the word “feminism”. The first performance of Maria Pinińska-Bereś took place in 1967. The artist became more interested in this medium in mid-1970s. Apart from femininity, nature was the aspect of life which assumed a crucial role in her performances. She loved nature from the early age and her love and empathy for it proved even more intimate than erotic aspects of life, which are shared with another person. Even before the motives of nature became a regular part of artworks in general, Pinińska referred to nature in her projects. It is worth emphasizing that she did not treat artworks related to nature as vehicles to express ideological concepts. So, generally speaking, her stance on this was quite similar to her approach to feminism in art.

Maria Pinińska-Bereś, performance “Kite-Letter” (1976)

Maria Pinińska-Bereś was a true individualist and she persistently followed her own path in the world of art. To be honest, she could not find any kindred spirit in this complex reality. Her only artistic supporter was her husband, Jerzy Bereś, who was a sculptor and a performer. Although they perceived themselves as two artists acting at totally opposite sides of avant-garde movement, their works were, in fact, complementary. Paradoxically, Jerzy Bereś was much more successful during Maria’s lifetime, but currently, it is her who is more recognised and whose works are constantly being studied and discovered anew. Her works are exhibited at world-class exhibitions (e.g. “The World Goes Pop” at Tate Modern), analysed in numerous publications on art theory and art history, but also on contemporary artwork restoration. The foundation named after her conducts research on performance reenactment, which has already become an impulse for many interesting artistic events. The works by Maria Pinińska-Bereś remain up-to-date. When we go beyond their easy, superficial interpretation, we have a chance to find solutions to many contemporary problems and comments on the most bothering issues which we observe around us.

Written by Oskar Hanusek

Maria Pinińska-Bereś, “Burning Giraffe” (1989)

[1] M. Pinińska-Bereś, „Z listu do Krytyka – Droga X.!” (manuscript, the archive of Maria Pinińska-Bereś and Jerzy Bereś Foundation, 1993), p. 1.

[2] M. Pinińska-Bereś, „Autorefleksja (II)” [the second version] (manuscript, the archive of Maria Pinińska-Bereś and Jerzy Bereś Foundation, 1991), p. 1.

[3] M. Pinińska-Bereś, „Ojciec” (undated manuscript, the archive of Maria Pinińska-Bereś and Jerzy Bereś Foundation), p. 2.

[4] Ibid.

[5] M. Pinińska-Bereś, „Gorsety i Wieże” (manuscript, the archive of Maria Pinińska-Bereś and Jerzy Bereś Foundation, 1994), p. 1.

[6] Ibid.

[7] M. Pinińska-Bereś, „Zeszyt z wiewiórkami” (manuscript, the archive of Maria Pinińska-Bereś and Jerzy Bereś Foundation, 1997), p. 4.

[8] M. Pinińska-Bereś, „O M.” (manuscript, the archive of Maria Pinińska-Bereś and Jerzy Bereś Foundation, 1996), p. 1.

[9] M. Pinińska-Bereś, „Zeszyt…”, op. cit., p. 3

[10] M. Pinińska-Bereś, „Gorsety…”, op. cit., p. 1.

[11] M. Pinińska-Bereś, „Mebelki” (manuscript, the archive of Maria Pinińska-Bereś and Jerzy Bereś Foundation, 1996), p. 1.

[12] M. Pinińska-Bereś, „Zeszyt…”, op. cit., p. 6

[13] M. Pinińska-Bereś, „O M. …”, op. cit., p. 1.

[14] M. Pinińska-Bereś, „Mebelki…”, op. cit., p. 1.

[15] M. Pinińska-Bereś, „Gorsety…”, op. cit., p. 1.

Maria Pinińska-Bereś, “Standing Corset” (1967)