The International Association of Art Critics is the world’s leading organization dedicated to the revitalisation and promotion of critical discourse. Founded in 1950, AICA comprises various experts eager to establish and expand international co-operation in the fields of artistic creation, dissemination and cultural development. The long-term objectives emphasise the global reach of the Association, its cross-cultural ambitions and interdisciplinary approach. The organization brings together over five thousand talented professionals from ninety-five countries worldwide, organised in sixty-three National Sections and an Open Section. I had the pleasure of speaking with Magdalena Ujma, the newly elected President of AICA Poland.

Magdalena Ujma has been active in the fields of art criticism and curation since the 1990s. She is an accomplished critic and essayist who has written essays for the collections New Phenomena in Polish Art after 2000 (2007) and Polish Female Artists (2011). Her book entitled Visual Art. The Scandals was published in 2011, and she has served as a member of many editorial teams. Magdalena also founded and ran NN Gallery in Lublin, and was Director of Cricoteka, the Centre for Documentation of the Art of Tadeusz Kantor; Curator at Art Bunker, Gallery of Contemporary Art in Kraków; and Curator at the Museum of Art in Łódź, among residencies at other esteemed institutions. She has curated or co-curated dozens of exhibitions and written hundreds of articles, reviews, and essays. Her interests lie in socially engaged art, institutional critique, feminism and the role of storytelling in contemporary art. Currently, besides leading AICA Poland, she is an independent critic and curator.

Magdalena Ujma, Photo by Jarosław Gawlik

Marek Wołyński: We’re having this conversation at the beginning of 2021, which seems likely to bring back some state of normalcy and restore direct interactions. Yet the world is still languishing in lockdown. How has the pandemic affected the work of art critics? Have they been motivated or frustrated by the departure from the traditional forms of art presentation in favor of a digital exhibition format?

Magdalena Ujma: I ask myself this all the time. There is no one good answer. First of all, it must be said that very few people can actually make a living by working only as art critics in Poland or any other place in the world. They usually take other jobs, often as curators or academics — researchers, teachers, employees of cultural institutions etc. Therefore, the impact of the pandemic on our profession (alongside restrictions in interpersonal communication and compulsory remote work) is far from equal as it depends on one’s other occupation beside that of an art critic. So academic teachers run their courses online and institution members keep working remotely.

Employees of cultural institutions with no permanent contracts, meaning freelancers and essentially the precariat, have found themselves in the most dire situation. Due to the pandemic these members of our community have lost all sources of income. As AICA Poland, we wrote the official letter on this matter to the Ministry of Culture and National Heritage. We’re carefully monitoring developments in cultural policy at the local and national levels. Currently, we’re conducting a more in-depth analysis based on the data on the living circumstances of people working in the cultural sector. This analysis will provide substance to our plea for the livelihood of art workers, especially critics, curators, event organizers and animators. Another Polish organization, the National Forum for Contemporary Art (OFSW), is also a very strong and vocal advocate of artists.

Since nowadays you can’t do research and verify your facts at the library due to the limited access, a comprehensive and meticulous critique becomes more difficult. Sure, there’s always the internet but it’s still quite deficient when it comes to obtaining knowledge. In Poland, we can meanwhile witness the ascendance of independent digital media, which began to flourish prior to the pandemic and gathered even more momentum afterwards. We’ve noticed a radical increase in podcast and film productions in particular. There’s an abundance of online radio stations, some of which are funded from listeners’ donations. Selected editors address the subject of visual arts, including Agnieszka Obszańska (Radio 357) and Karolina Plinta (Radio Kapitał). Institutions launch their own series of meetings and programmes with the participation of curators and critics. A good example would be Tomasz Fudala and Natalia Sielewicz contributing to the blog and meetings revolving around the Warsaw Biennale hosted by the Museum of Modern Art in Warsaw.

The written word and visual or multimedia content go hand in hand in some fine online magazines dealing with critique, such as RTV Magazine of the Municipal Gallery Arsenał in Poznań and Postmedium issued by the University of the Arts in Poznań. They were founded before the pandemic, which has only highlighted the relevance and significance of the digital channel of communication.

Paulina Olszewska’s Presentation (Instagrammable. Instagram in the context of the current art critique) at the ‘Art Criticism Today: Language, Economy, Politics’ conference organised by AICA Poland, Warsaw 2019, Photo by Bartłomiej Gutowski

MW: Art critics function somewhere between artists, curators and viewers — they’re outstanding mediators who make art and its contexts more accessible to audiences. One needs to possess an incredible openness and a variety of skills to operate effectively in the art world. How do the art critics associated with AICA perceive their role within the art world?

MU: The Polish section of AICA has 141 members, who are involved in the critical field in a number of ways. Critics affiliated with AICA Poland are either persons working at universities, which are in the majority (almost 50% of all our members), or they are curators, i.e. representatives of the second largest group at our organization (27%). What’s interesting is the fact that critics working in the media whose profession is their primary source of income constitute just under 3% of the entire membership. In addition, approximately 5.5% of people have no permanent employment contracts. Such a huge diversity makes it impossible for us to adopt a unified approach and strategy with regard to their discipline. Members of AICA include critics studying the subject at universities and art academies, as well as editors of art magazines such as Restart or Szum, authors of essays published in exhibition catalogues and blogs engaging in critique (e.g. Marta Kudelska and Karol Sienkiewicz), and last but not least persons collaborating with the media, e.g. the filmmaker shooting features inspired by the lives of Polish contemporary artists (Łukasz Ronduda). Broadly understood critique is viewed as a whole spectrum of activities associated with contemporary art.

Even enumerating the professional groups of authors dabbling in critique who make up AICA Poland gives a person some idea about the variety of ways in which one could define critique. One could venture the statement that thus we have exhausted its definition, encompassing not only the assessment, but also interpretation of art, as well as the postulative approach on top of all that: diagnosing the courses of artistic transformation, putting forward postulates about the future and drafting manifestos.

If I were to define the nature of critique in Poland — an appreciation of its high quality and the complaints about its dwindling significance in the modern world notwithstanding — then I would point to the emergence of strong new voices and styles of writing not without grit. Unfortunately, there’s no platform for multifarious forms of critique offering a place for debates and confrontations. This role was played by Obieg magazine, published online in its old formula until 2015. Instead, there’s an awful lot of waffling, critique in the form of lengthy essays that often position themselves on the verge of an academic and critical writing. Hardly ever does one encounter any experimental forms, that’s a pity. Personally I believe we also lack metacritique, in other words we could use some theorizing about the critique itself, its strategies, languages or styles.

Dorota Grubba-Thiede speaking at the ‘Art Criticism Today: Language, Economy, Politics’ conference organised by AICA Poland, Warsaw 2019, Photo by Bartłomiej Gutowski

MW: Polish contemporary art is well known for its engagement in current social issues. 2020 brought on a plethora of unprecedented events: BLM protests, women’s, workers’ and business owners’ strikes, and many local socio-political protests (not to mention the issue of / those around global warming). Do art critics in Poland engage in current local and global social issues? What importance does a civic dialogue hold in the eyes of critics?

MU: The Polish Section of AICA is drafting a statement regarding this matter. The tradition of involving the organization in the country’s public life was initiated by our former board headed by Luiza Nader (2018-2020). We believe this activity is of grave importance. Social engagement coincides with the role of intellectuals, which we clearly are. It would go against the purpose of our organization’s existence if we didn’t make statements about matters pertaining to the state of our reality, democracy and socio-political phenomena, with a particular emphasis on issues surrounding visual culture and persons involved in its creation, dissemination and reception. AICA was founded as an international organization affiliated with UNESCO right after the Second World War. One of its original and still relevant objectives was to promote the idea of critics’ responsibility towards artists and audience. In my opinion, we will be stranded at the peripheries and marginalized if we shy away from taking an open stance on matters of public importance. For this reason, we correspond with the city mayors as well as the Ministry of Culture and National Heritage (most recently on the subject of the aid offered to people working in the cultural sector in the face of a pandemic), we support organizations, promote good practices among governing bodies, institutions of culture and employees of these institutions, we champion transparency and following procedures while organizing the competitions to choose next directors of institutions, lately in Wrocław and Łódź.

The public at the ‘Art Criticism Today: Language, Economy, Politics’ conference organised by AICA Poland, Warsaw 2019, Photo by Bartłomiej Gutowski

MW: What areas will be at the center of AICA Poland’s attention in the upcoming years? What initiatives are of the utmost priority to the organization, in your opinion?

MU: The Polish Section of AICA abides by its clearly defined set of goals and tasks specified in our election programme of 2020. Apart from myself, the board of AICA Poland is comprised of my esteemed colleagues: Małgorzata Kaźmierczak and Piotr Kosiewski as Vice-Presidents, as well as Anna Markowska, Bartłomiej Gutowski, Łukasz Guzek and Arkadiusz Półtorak.

One of our important goals is to include underrepresented professional groups of critics in the association, such as people working at media organizations, and accept members from a variety of locations other than the big cities, because the culture in the countryside is shaped by these small communities. We believe they must be established and supported properly. Of course, there’s more. Some of our most significant initiatives center around the archiving of critics’ works. Although we’re incapable of amassing these archives on our own, we can still seek them out, collect information about their existence, compile lists, arrive at methodologies to study the archives etc. The notions of memory and history of a discipline are related to the archives. Following the efforts of the former board, we intend to propagate the subject of critique as a research issue to be studied. Another very important mission of ours is to examine the current state of art criticism in Poland from the perspective of the professional status of critics and critique as an actual profession. We would continue the research conducted by AICA Poland in 1980 and compiled in the famous report written by Janusz Bogucki, Wiesław Borowski and Andrzej Turowski. The project will be spearheaded by Arkadiusz Półtorak. As I’ve already mentioned, our mission is responding to what’s happening here and now, expressing our opinion so that the voices of our community members are heard loud and clear in the public debate. Yet another incredibly important project of Małgorzata Kaźmierczak’s is based on a collaboration between the countries in this part of Europe, such as the Czech Republic, Slovakia and Hungary, to create a separate section of AICA International that would represent our interests and strengthen our position.

MW: You have remarkable experience in curation and art criticism. To a certain degree these disciplines are complementary, but at the same time they remain pretty different. How does your experience as a curator collaborating directly with artists inform your activity as an art critic?

MU: This question deals with the evolutionary trajectory of my critique. I started out as a writer. Soon I didn’t pull my punches and tried very hard to pass vicious and independent judgment with various degrees of success. Some of my biting remarks fell on deaf ears, some artists wanted to sock me in the face (Alicja Żebrowska, for instance). In the early days, I attempted to preserve my autonomy which I naively took to be an isolation from the art scene. My writing has developed naturally over time as I have got to know artists in person, work at galleries, become part of this community. However I gradually stopped publishing reviews after I became a curator. In my mind, it would be an unethical behavior susceptible to manipulation: heaping praises on the artists you collaborate with, lambasting your competition, and so on. I started penning in-depth essays about the creative practice of selected artists that stemmed from my connections, previous collaborations and mutual understanding. Additionally, my pieces were addressing the topics I explored as part of my curatorial practice (e.g. countryside and peasantry, landscape, issues related to the work of female artists).

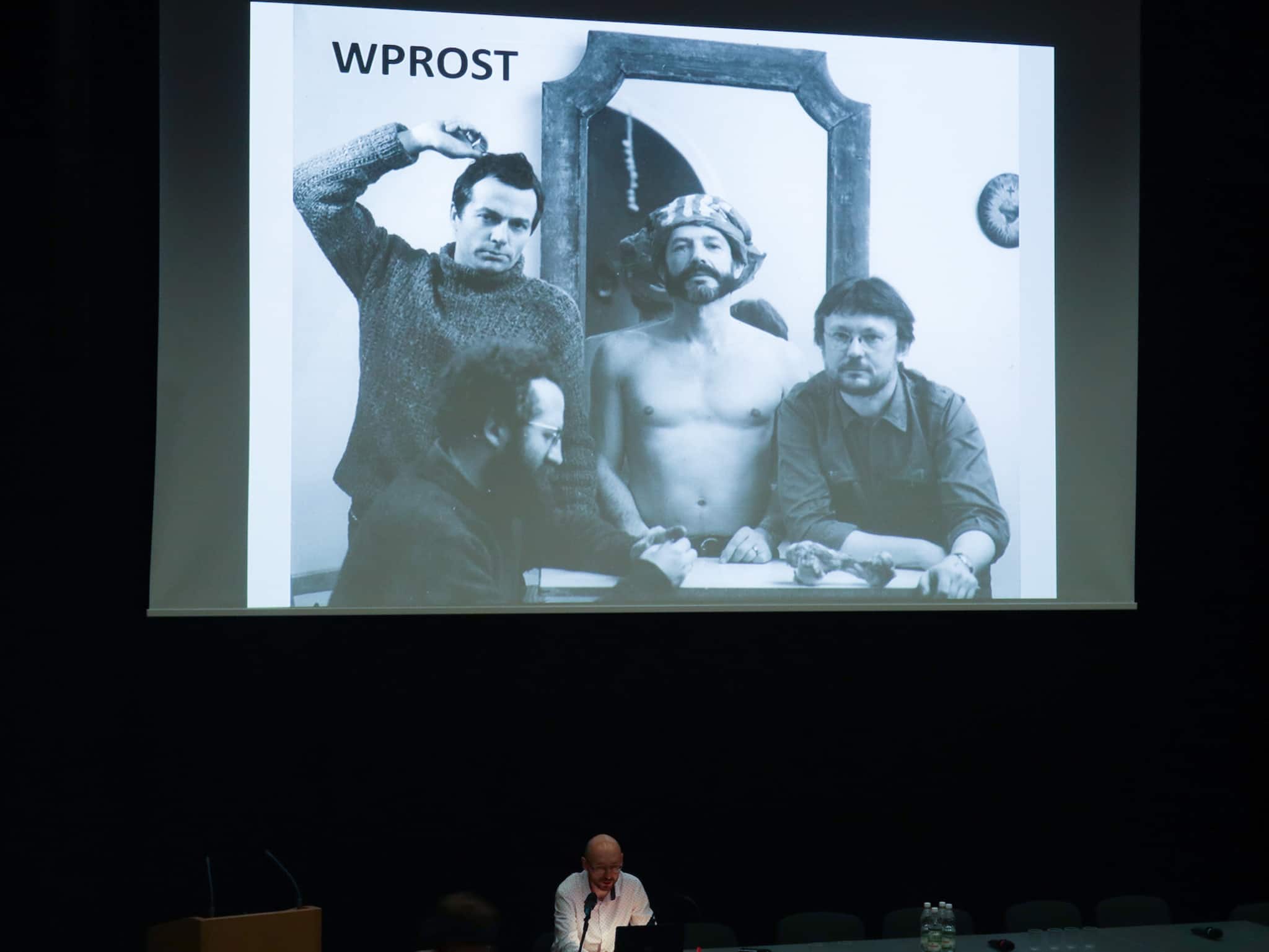

Marek Maksymczak’s Presentation (Freedom on Commission: A Critic in Collaboration with the Security Service) at the ‘Art Criticism Today: Language, Economy, Politics’ conference organised by AICA Poland, Warsaw 2019, Photo by Bartłomiej Gutowski

MW: Gradually, art critics have gone beyond the conventional form of the written word, using innovative means of communication, expression and interaction with audiences. Jerry Saltz — one of the most revered art critics in the English-speaking world and winner of the Pulitzer Prize for criticism in 2018 — runs an Instagram account with half a million followers. He posts an explosive mixture of content: from descriptions of artworks and reports from exhibitions to politically engaged messages and reposts from other accounts.

Similarly, Waldemar Januszczak — one of the leading art critics in the UK — successfully produces and posts online short films that take an unorthodox approach to the presentation of art history concepts, including the series The Singing Art Critics. How about the Polish art critics? Are there any initiatives exploring alternative channels of communication to better connect with audiences?

MU: First of all, art critique in Poland is still perceived largely in terms of writing texts, so there’s very few attempts at offering criticism in the form of regularly updated podcasts or videos. Apart from radio stations on the internet talking about visual culture, among other things, all major art institutions organize online events featuring critics. Numerous fascinating online magazines (Dwutygodnik, Szum, Postmedium, Miejsce, Przekrój) publish texts accessible not only to specialists in the field, but also laymen. What is more, Kultura liberalna and Krytyka Polityczna magazines feature art-related content. The topics of institutional critique and cultural policy of local and state government are tackled nowadays more often than they used to be.

Besides a few exceptions, well-known and visible art critics who would commit themselves to finding new ways of engaging audiences simply do not exist. I believe that this is related to the lack of professional art critics in Poland. The BWA Sokołowsko’s podcast run by Michał Suchora, however, is an interesting project. It is centred around art, ecology and politics and was initiated on the hundredth anniversary of Joseph Beuys’ birth.

MW: Polish art critics have gained international appreciation and recognition. Marek Bartelik was the former President of AICA International in the last decade, while Małgorzata Kaźmierczak is the current Vice-President. Why are Polish critics held in such a high regard? What traits set them apart from the others?

MU: To name just a few: drive, passion and brevity steeled in unfavorable conditions. In Poland, only those who really care can become critics, those who can survive against all odds, grit their teeth, find a job to pay the bills and engage in critique because that’s their passion.