MoMA PS1 has announced it will present the first New York museum exhibition of visionary feminist and activist artist Niki de Saint Phalle. The survey ”Structures for Life” will highlight her interdisciplinary approach and engagement with key social and political issues.

In 1986 Niki de Saint Phalle portrayed herself with the following words: ”Niki is a special case, an outsider. Most of Niki’s sculptures have a timeless quality, they are reminiscences of ancient civilisations and dreams. Her work and life are like a fairy-tale full of quests, evil dragons, hidden treasures, devouring mothers and witches, birds of paradise, good mothers, glimpses of paradise and descents to hell.” The French-American artist wrote about herself in third person as if she was describing a heroine – not without reason. During her fruitful career she subtly yet audaciously sowed the seed of disturbance in the realm of a deeply masculinized artworld. She created works that give the power to exorcise intimate traumas, to extricate from restraints and hurtful experiences. Despite an overflow of almost hallucinatory colours and whimsical shapes indicating charming naivety, roguishness or flippancy, her oeuvre became a critical response to the world’s wickedness and brutality.

Niki de Saint Phalle at Tarot Garden, Garavicchio, Italy, 1980s. Photographer unknown.

Niki – or Catherine Marie-Agnès Fal de Saint Phalle to be exact – owed blue blood to her father, Count André-Marie Fal de Saint Phalle. Even though she never paid attention to the aristocratic background, it made her life – oscillating between Paris and New York – a little bit easier. As a young woman of noble beauty she graced the covers of prestigious fashion magazines. However, the photoshoots for ”Vogue” and ”Elle” not only sugar-coated Niki’s rebellious temper but also veiled her family with an illusion of decency. In fact, de Saint Phalle – whose upbringing was accompanied by the crucifix and a disciplinary whip – endured her mother’s violence and suffered sexual abuse from her father. The hell-like home left unhealed wounds on both of her younger sibilings, who would commit suicide as adults. Niki’s mother – an abusive bigot that looked away from her spouse’s heinousness – became the reason why de Saint Phalle was rebelling against the societal pressure and gender roles. She objected to being a submissive daughter, a disciplined pupil from a catholic school, a mindless model, a wife, and a mother. Even the marriage to a novelist Harry Matthews did not forbear the anarchistic personality of the artist-to-be. In 1953 a battle between her family’s expectations and her own artistic aspirations contributed to Niki’s mental breakdown. However, that same year, while drawing her first lines on paper she discovered the cathartic and curative power of art. ”Painting calmed the chaos that shook my soul. It was a way to tame those dragons that have appeared throughout my work.”

Taming the demons of the family home coincided with Niki’s first painterly experiments. Plastic toys, ceramic shards, garbage, knives and devotional items came to burst into the canvases, creating dense assemblages. This almost obsessive hoarding of junk and tchotchke was planted in Niki’s mind by her long-time friend, Jean Tinguely. In the early 1960s their art alignment resulted in the series of painterly actions ”Tirs” (”Shooting Paintings”). De Saint Phalle – armed with a rifle – was firing at the plaster reliefs that concealed some bottles of paint and aerosol sprays. Explosions of liquid pigments covered the white surface with colorful splashes. ”I shot because it was fun and made me feel great. I shot because I was fascinated watching the painting bleed and die. I shot for that moment of magic. Red, yellow, blue – the painting is dead. I have killed the painting. It is reborn. War with no victims.” These constructive-destructive happenings resembled carnival games. Pulling the trigger gave some sort of entertainment as well as releasing frustration and anger. A woman aiming a firearm at art in the name of art – this was a novelty that brought Niki de Saint Phalle to the artworld’s attention with the speed of a bullet. Yet in 1961 Pierre Restany encouraged her to join the Nouveau Réalistes, and she did, becoming the first woman in that group.

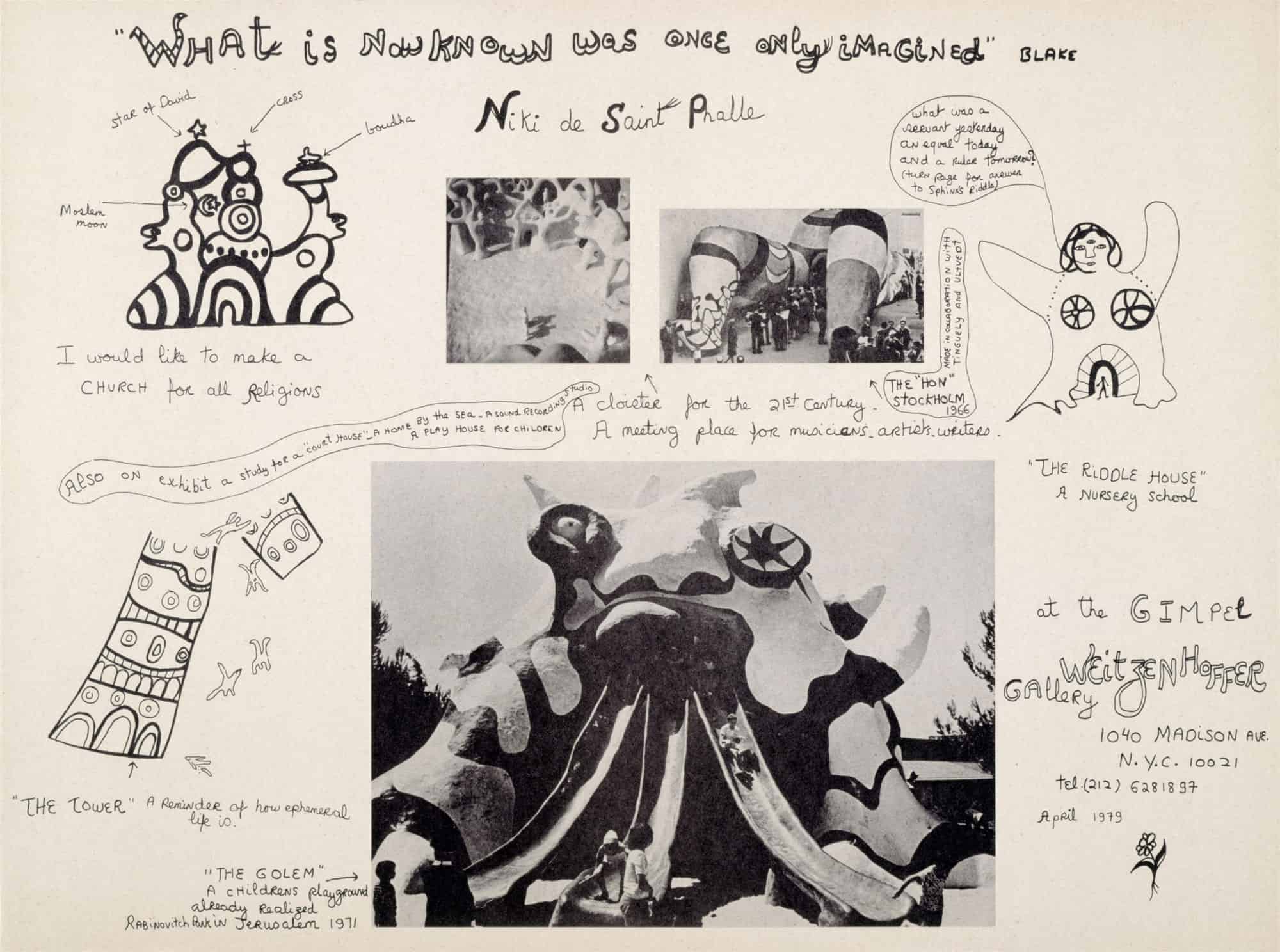

Niki de Saint Phalle. What is now known was once only imagined. 1979. Offset print. © 2020 NIKI CHARITABLE ART FOUNDATION. Photo: NCAF Archives

The reliefs embrued with paint put down the stereotypes, conventions and brassbound traditions. A shot lacerated the ordeal of the past. It is proved by the assemblage entitled ”La Mort du Patriarche” (1962/72) – a plaster human figure with broad shoulders and a small head marked by the symbols of violence and power: dismembered dolls, a plane, a machine gun, and a space rocket. Niki shot at it in the movie ”Daddy” (1973), retaliating against her father for the harm he had caused and taking vengeance for very form of abusive male domination. However in 1963 the artist quit her own frenzy, admitting: ”I had become addicted to shooting, like one becomes addicted to a drug.”

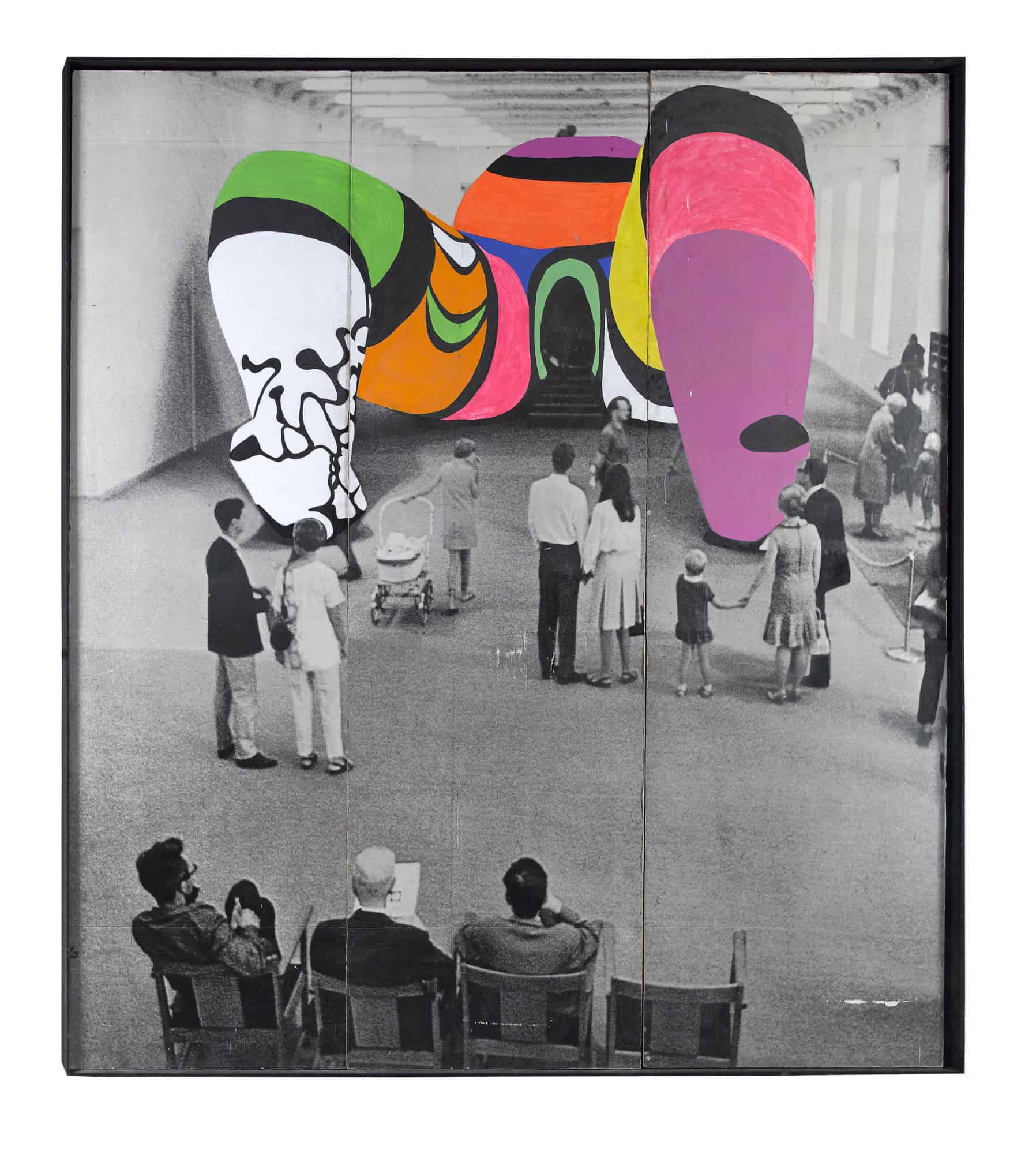

After the ”Shooting Paintings”, de Saint Phalle started exploring many facets of womanhood. She became well known for creating ”Nanas” – energetic life-size female figures in different dance-like poses, which epitomized sensitivity, tenderness and vitality. Archetypical matriarchs and fertility goddesses with Rubenesque shapes; the dancing victors of modernity were nothing like the rickety, passive and harried brides that Niki portrayed earlier (”Cheval et la Mariée” 1963; ”Bride” 1965). Liberated from the gender roles, they celebrate femininity. The early ones, presented at the exhibition ”Nana Power” in Paris in 1965, were made of wires, textiles and papier-mâché. Short after – due to the popular usage of polyester resin (which damaged the artist’s health) – ”Nanas” became strong, large scale outdoor statues placed in city squares (”Hannover Nanas” 1973) or even scultural-architectural megaconstructions such as ”Hon – en katedral” (1966). The latter – created with the help of Tinguely and Per Olof Ultvedt – was a 82 feet long, 30 feet wide reclining woman entirely filling the largest room at the Moderna Museet in Stockholm. Entering this giant Nana through her vagina, the audience found themselves in an amusement-park-like environment: a milk-bar was in one breast, a goldfish pond occupied the site of the womb etc. It was a quirky example of the modern architecture parlante. Above all, ”Hon” – despite its whimsical nature – was not a fulfillment of secret sexual fantasies but a space encouraging to learn about, celebrate and demythologize women’s bodies. ”The happy, giant creature embodied for many visitors, and also for myself, the dream of the return to the great mother. Entire families with little children came to the museum to see her” – stated de Saint Phalle.

Niki de Saint Phalle. Tarot Garden. 1991. Lithograph, 23.7 x 31.5″ (60.3 x 80 cm). © 2020 NIKI CHARITABLE ART FOUNDATION. Photo: Ed Kessler

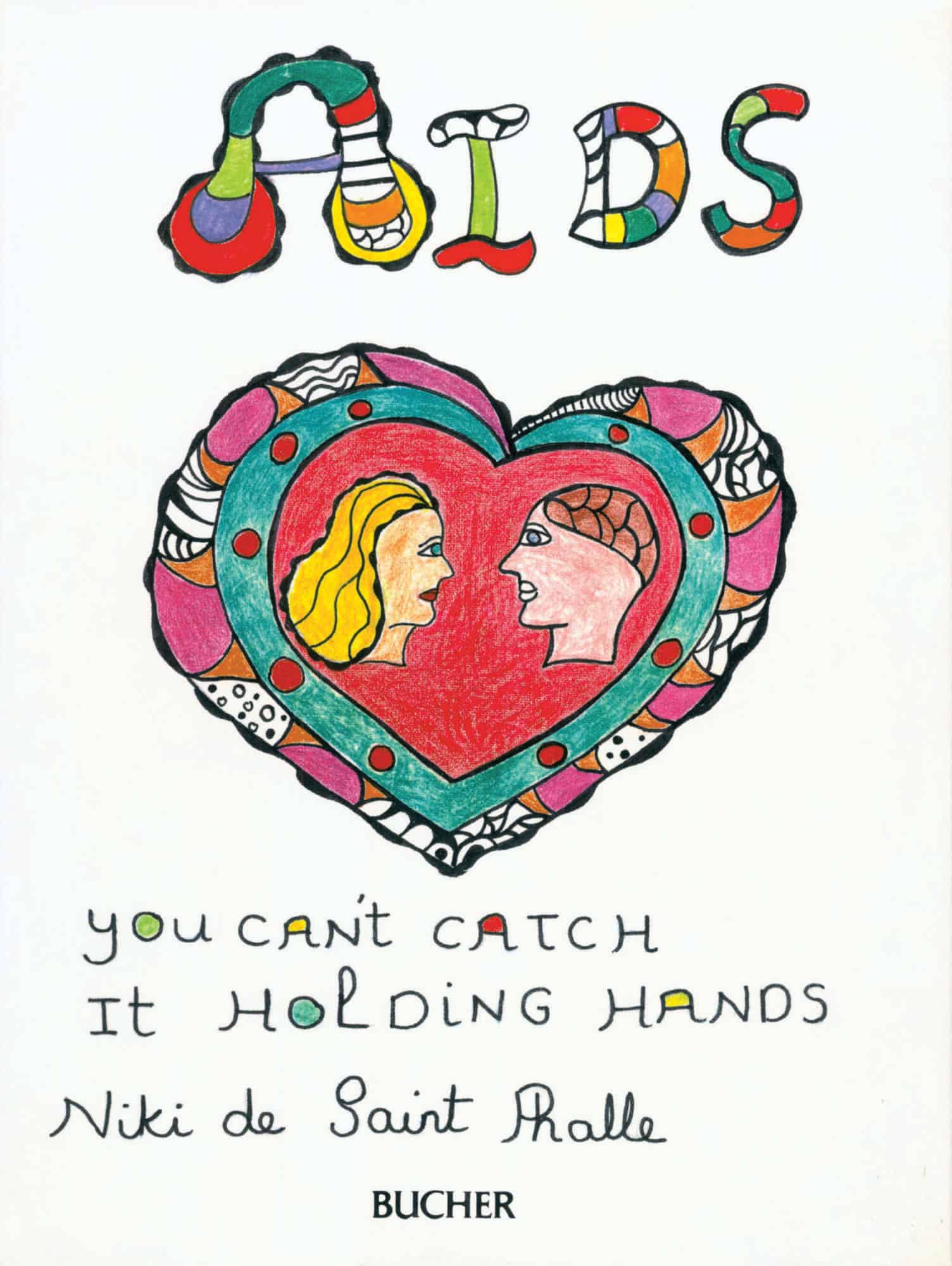

Without a doubt the art of Niki de Saint Phalle might be seen in terms of a private as well as political statement. In 1963 she pointed her firearm at the plaster heads of Castro, Lincoln and Khrushchev among others. In later years she advocated against the gun industry, denounced the NRA, defended women’s reproductive rights and commented on world hunger, domestic abuse, global warming and environmental neglect. From 1983 to 1986 de Saint Phalle wrote and illustrated ”AIDS: You Can’t Catch It Holding Hands” (in collaboration with Swiss AIDS specialist Prof. Silvio Barandun). She delivered straightforward information about the transmission of HIV in the form of playful and multicolored drawings.

The most valuable aspect of de Saint Phalle’s art lies in the artist’s ability to make her intimate, personal experiences universal and communal. Although her dreamlike, fey, quasi-primitive works could and did expose her to ridicule, she created art that tamed the demons – works infused with empathy, encouragement and ”you-are-not-alone” power. Throughout her rich career she strongly believed in the healing force of art – whether it cures her own or the world’s wounds.

edited by Laura Heuberger

Niki de Saint Phalle: Structures for Life

Dates to be announced

MoMA PS1 in New York

The exhibition is organised by Ruba Katrib, Curator, MoMA PS1

Niki de Saint Phalle. Photo de la Hon repeinte. 1979. © 2020 NIKI CHARITABLE ART FOUNDATION. Photo: Katrin Baumann

Niki de Saint Phalle. Book cover for AIDS, you can’t catch it holding hands. 1986. © 2020 NIKI CHARITABLE ART FOUNDATION. Photo: NCAF Archives

Niki de Saint Phalle. Interior view of Empress, Tarot Garden, Garavicchio, Italy © 2020 FONDAZIONE IL GIARDINO DEI TAROCCHI. Photo: Peter Granser