The recently opened exhibition of a New York-based artist Rebecca Quaytman at Muzeum Sztuki in Łódź is a return to the artist’s very beginnings and a retrospective of sorts, presenting topics that have continually run through her work over the last 20 years. At the exhibition, older works are juxtaposed with over 30 new ones. The artist retells themes she finds crucial, reinterprets them and skillfully creates new contradictions and narratives. She writes a book. Her subsequent exhibitions since 2001 are chapters of the painting odyssey. They resemble an artistic journal or a calendar, and each constituent part records dialogues with different artists Rebecca encountered. The audiences can familiarize themselves with the pages of this new chapter, that are placed on shelves and reveal a thrilling narration. We can recognize the underlying idea, the main protagonists of the chapter and the symbolic end, which simultaneously, introduces the next chapter the artist already started envisioning.

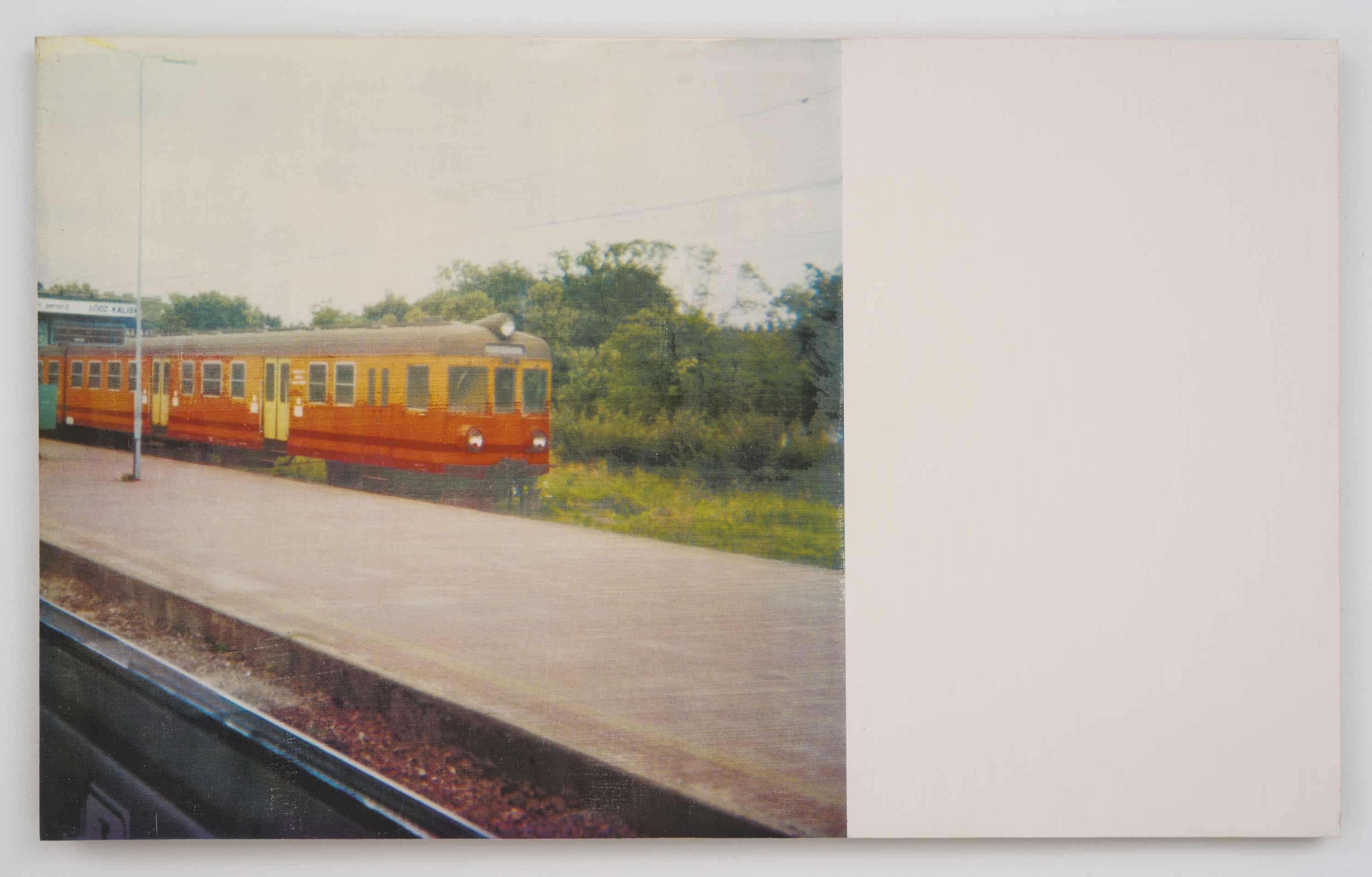

R. H. Quaytman. The Sun Does Not Move. Chapter 35, Optima, Chapter 3, 2004, © R.H. Quaytman

Rebecca Quaytman is mainly inspired by the present times and the past. She likes to take a comprehensive look at past and present events. Family’s private history, the history of art, history of places Quaytman visits, emotions and the direct and ‘current’ experiencing of the exhibition space – all these give rise to a coherent whole. The images archived in the artist’s head overlap and penetrate one another. Her former works form a creative dialogue with the ones she has newly created as well as works by other artists. Such references to different works are truly fascinating. Besides constructivist and abstract compositions, we can observe the Amazons exhibiting their sexuality. We also see Persian women that reemerge in Rebecca Quaytman’s work at different times of her career. We saw them in Łódź in the paintings from Chapter 35 entitled “The Sun Does Not Move”. They were also clearly noticeable at the exhibition at Wiener Secession two years ago where “Chapter 32” was presented to the public. Those works were inspired by Otto van Veen’s painting entitled “The Persian Women and Amazons and Scythians”. At a meeting in Vienna in 2017, Rebecca Quaytman admitted that she was fascinated with female power and the story presented by van Veen that was hidden in the painting and was not referring to Christian narrative. The story itself is symbolic, but indeed, extremely interesting. The Persian women is a story from Plutarch’s “On the Bravery of Women”. The action takes place during the Persian Wars and depicts men who behaved like cowards wanting to flee and hide within the city walls. At that time women confronted the men and lifted up their own garments, allowing the female reproductive organs to show. They mockingly asked the men whether they wished to go back to the womb where they came from, i.e. to the status quo (understood as the women’s womb, a home, a city, old rules). However, as it turned out, there was no return. These bare women may have looked powerless and vulnerable, but they forbade the men to go back to the city. The humiliated men had no choice but to turn around, beat the enemy and only then were they allowed to return to their women.

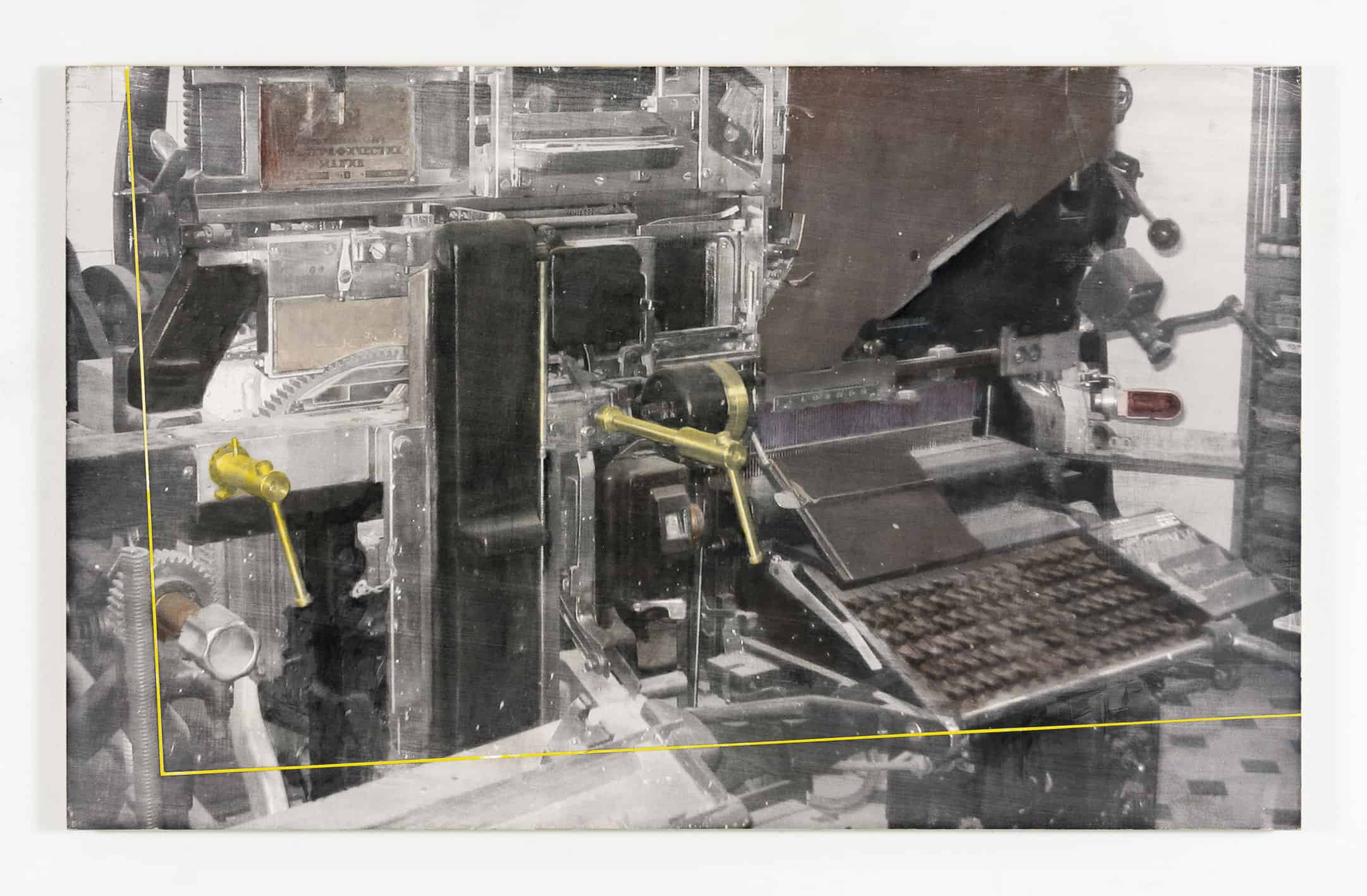

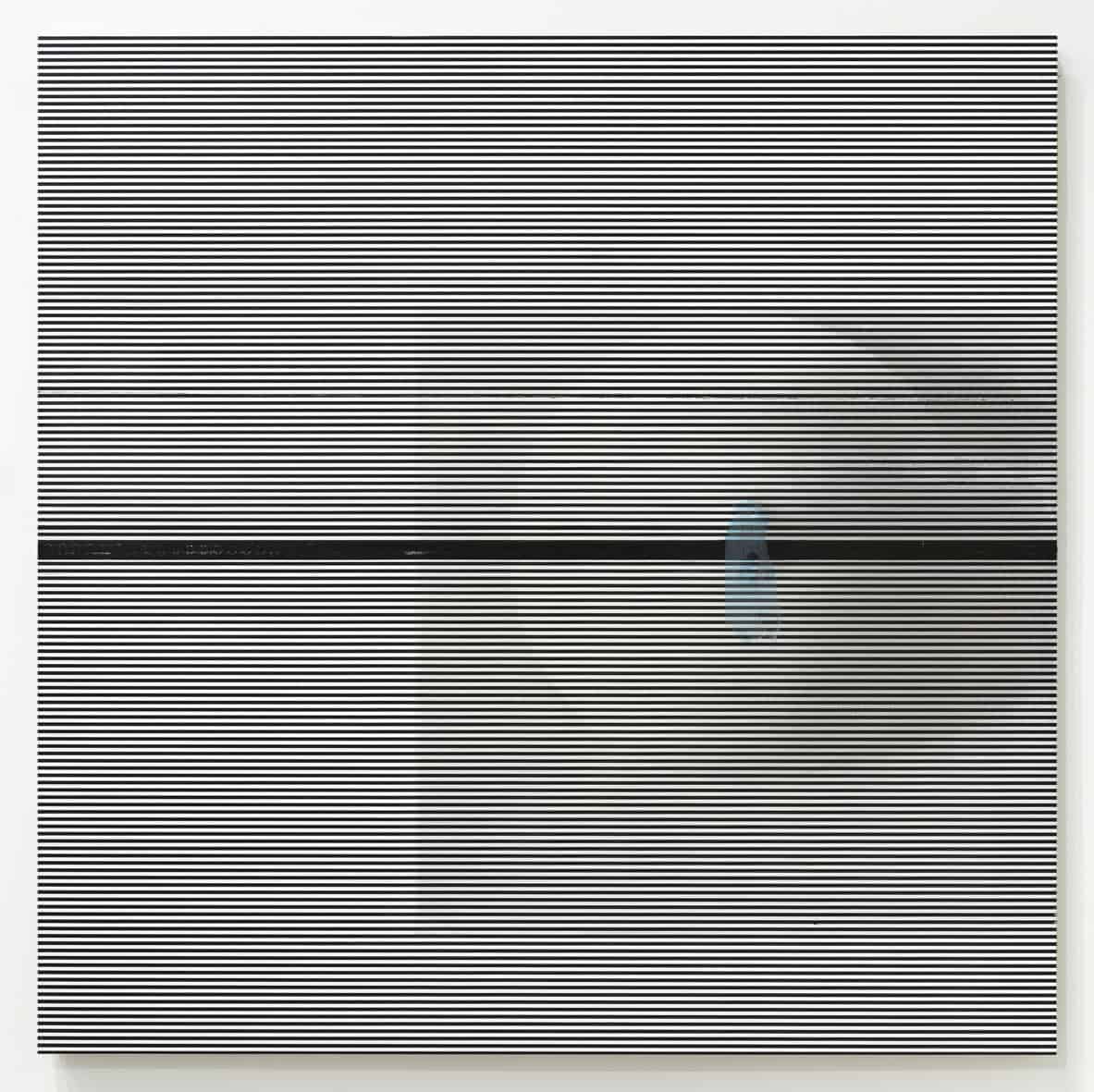

On the one hand, the story is about women’s power symbolized by their bare wombs and breasts. We see women who derive new power from their natural features – features which defined women from the very beginning of mankind. Limitations became a new tool. On the other hand, what strikes us is the simultaneity of images. The story of the Persians in the painting by Otto van Veen is presented as a single frame, although, in fact, the described action spread over time and took place in various locations. Simultaneity is what we see in Rebecca Quaytman’s paintings as well. The contemporary artist appropriated the work by the old master and despite her interventions, all gestures/layers show through. The work by the old master was initially recorded in the form of a photograph. It was later transported and converted into a screen print. Stripped of its uniqueness, the picture loses even more of its distinctive shapes that now become blurred. This effect is achieved thanks to an optical manipulation which relies on human sight imperfection, simple divisions and rhythmicality. One needs to come really close and look hard in order to see the original image. It is extremely difficult to notice it though, because abstract stripes/interventions make looking at the picture quite painful.

R. H. Quaytman. The Sun Does Not Move. Chapter 35, The Sun Does Not Move, Chapter 35, 2019; © R.H. Quaytman

We are not able to go back and see the then ‘status quo’ (just like the Persians were unable to do it); we are being pushed away from it. Our perception mechanisms are being challenged and the way they function is fully revealed and symbolically ridiculed. Our eyes demand of us that we move, step further back and look from different angles to see more details. Many antagonistic forces pull us simultaneously. They drag us and push us away. An old master and a contemporary artist, antiquity and modernity, familiar story and a secret. Gaps in the picture and the inability to see the entire image make us anxious and astonished at the same time – the Freudian feeling ‘Unheimliche’.

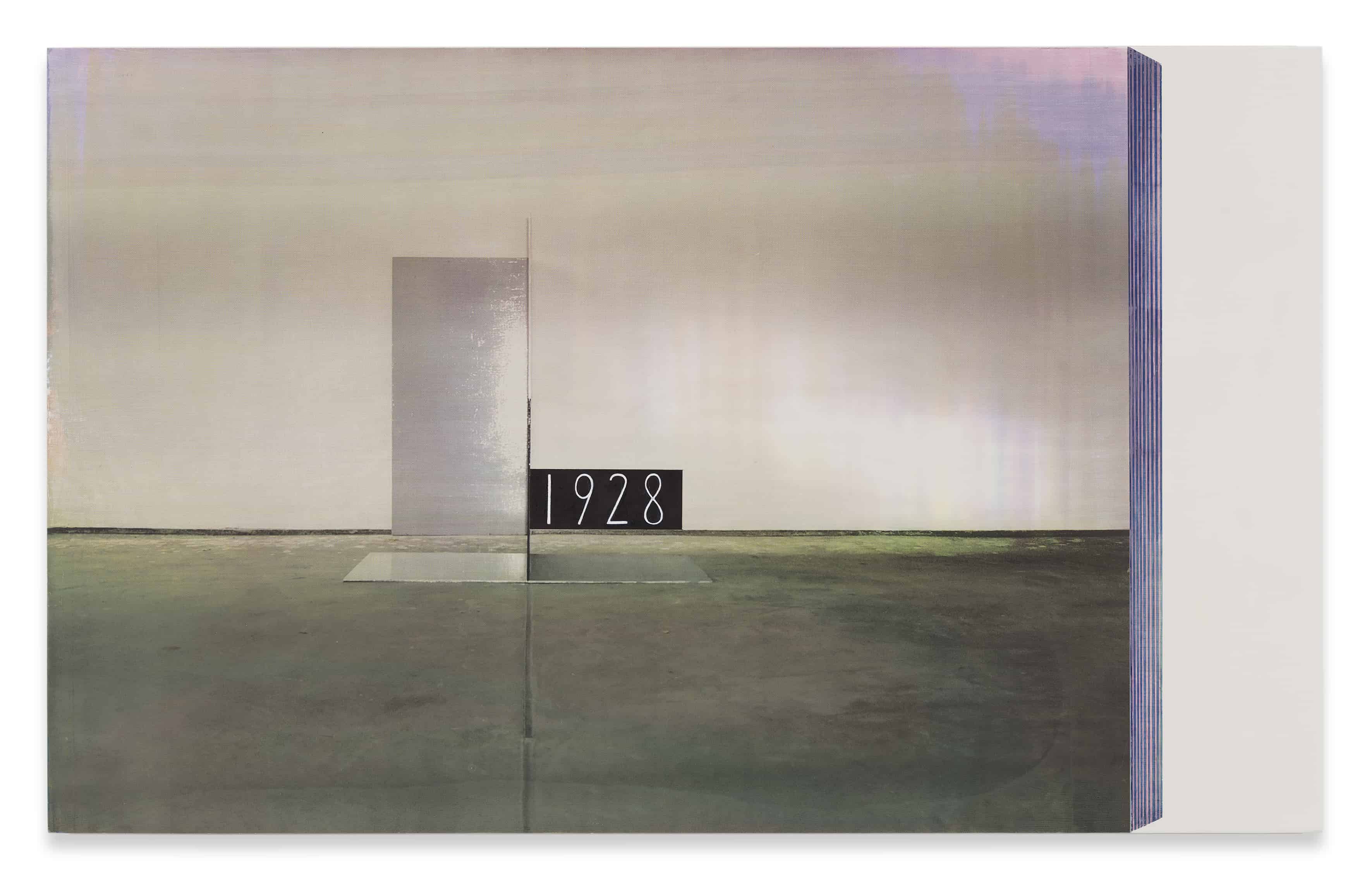

Consequently, these opposite movements start to define our space. A flat picture becomes three-dimensional. When we take a step to the side, we notice that it is an object. This is not, however, due to the painting surface being perpendicular to its edge. Rebecca Quaytman paints on wood panels with edges trimmed at an angle. In this way she moves the painting away from the wall allowing air to get behind the painting’s back. Apart from that, it stands on a shelf, just like a book. This creates a spatial composition.

In 1929, Katarzyna Kobro wrote in the Europe periodical, issue no. 2: “„[…] Sculpture is a part of the space in which it is located. […] Sculpture enters space and space enters the sculpture. The spatiality of its construction, the connection between sculpture and space, force sculpture to reveal the sincere truth of its existence. That is why there should be no random shapes in sculpture. […]”

The Sun Does Not Move, Chapter 35, 2019, © R.H. Quaytman

When it comes to works by Rebecca Quaytman, shapes and sizes of picture-objects are by no means random. The above quote from Katarzyna Kobro was cited for a reason. Eight basic dimensions of Rebecca Quaytman’s works are the result of her research on the golden ratio and works by Katarzyna Kobro, specifically, the “Spatial Composition 2” (1928). The composition was 50 cm high. Quaytman took this number, multiplied it by the golden number, i.e. 1.618, obtaining the initial dimensions: 20 x 32.36 inches. All later works are further mutations and various configurations of these dimensions.

The figure of Katarzyna Kobro and inspiration by her works leads us to another aspect of artistic activity of the American artist we are discussing. Quaytman’s exhibitions are, in fact, a dialogue not only with other works and artists, but also with an institution. The theatrical setting of the palace building of Muzeum Sztuki in Łódź becomes a stage. On this stage a tale unfolds. The content is communicated through pictures/actors. The theatrical movement and rhythm (rythm was extremely important for Katarzyna Kobro and Władysław Strzemiński) are embodied in the dance the audience performs as a result of being dragged towards and pushed away from the works.

R.H. Quaytman, Łódź Poem, Chapter 2 (Replica of Kobro’s Spatial Composition, 1928), 2004

As I mentioned before, the title of the work series presented in the museum space is “The Sun Does Not Move. Chapter 35.” The 35th tale. , But the first story, “The Sun. Chapter 1”, was also presented in Łódź. Everything started in this city. At the exhibition we can see a portrait of Quaytman’s grandfather, whose story encouraged the artist to come to the city in 1999. Her grandfather was an emigrant with Jewish origins and came from Łódź. At the Muzeum Sztuki in Łódź Quaytman familiarized herself with works by Kobro and Strzemiński. Her first encounter with their works was indeed significant. At that time painting was experiencing crisis internationally – no new solutions and possibilities to develop painting technique were thought to be possible. It seemed that the technique reached the point in its development where nothing else or more could be done. Quaytman experienced quite similar crisis and tried to find a new direction for her activity and painting as such. She then embarked on a journey in search of her own roots. The journey was a decisive factor when it comes to how her work developed. The works by the two prominent Polish artists from Łódź I mentioned above, gave her an answer to her questions about space, perspective and form, and helped her understand what a work of art could be like. At that point she started researching physical aspects of paintings and how paintings can interact with the space and the audience. She takes photographs of artworks (starting with the “Spatial Composition” by Katarzyna Kobro and continuing with van Veen’s painting later on) and flattens them out, rubs part of the story they present away and shows that it is impossible to capture (‘return to’) the status quo of a photographed object. She symbolically ‘ridicules’ photography and painting, as if inducing them to further fight, but at the same time making us accept their inherent properties and limitations.

R. H. Quaytman. The Sun Does Not Move. Chapter 35

Curated by Jarosław Suchan

08.11.2019 – 23.02.2020

ms1, Więckowskiego 36, Łódź

R. H. Quaytman. The Sun Does Not Move. Chapter 35, The Sun, Chapter 1, 2001, © R.H. Quaytman

on the left: The Sun Does Not Move, Chapter 35 [Cherchez Holopherne], 2019; oil, tempera, gesso on wood; 12 3/8 x 20 x 3/4 inches (31.4 x 50.8 x 1.9 cm); Miguel Abreu Gallery, New York;

on the left in the background: The Sun Does Not Move, Chapter 35 [K8 Hardy], 2019; oil, silkscreen ink, gesso on wood; 20 x 32 3/8 x 3/4 inches (50.8 x 82.2 x 1.9 cm); Miguel Abreu Gallery, New York

on the left in the distance: Son, 2011; lithographic ink, gesso on wood; 20 x 20 x 3/4 inches (50.8 x 50.8 x 1.9 cm); Miguel Abreu Gallery, New York

in the middle in the distance: The Sun Does Not Move, Chapter 35, 2019; oil, gesso on wood; 52 3/8 x 52 3/8 x 1 1/4 inches (133 x 133 x 3.2 cm); Miguel Abreu Gallery, New York

in the foreground: The Sun Does Not Move, Chapter 35, 2019; acrylic, silkscreen ink, gesso on wood; 52 3/8 x 52 3/8 x 1 1/8 inches (133 x 133 x 3.2 cm); Miguel Abreu Gallery, New York;

in the background: The Sun Does Not Move, Chapter 35, 2019; silkscreen ink, gesso on wood; 32 3/8 x 52 3/8 x 1 inches (82.2 x 133 x 2.5 cm); Miguel Abreu Gallery, New York

on the left in the distance: The Sun Does Not Move, Chapter 35, 2019; gesso on wood; 20 x 32 3/8 x 3/4 inches (50.8 x 82.2 x 1.9 cm); Miguel Abreu Gallery, New York;

in the middle in the distance: O Topico, Chapter 27, 2014; encaustic, acrylic, polyurethane foam, gesso on wood panel; 40 x 43 1/2 x 27 inches (101.6 x 110.5 x 68.6 cm); Inhotim Collection, Brazil

in the foreground: The Sun Does Not Move, Chapter 35, 2019, gesso on wood, 20 x 32 3/8 x 3/4 inches (50.8 x 82.2 x 1.9 cm), Miguel Abreu Gallery, New York

in the background: The Sun Does Not Move [Malevich. White on white], Chapter 35, 2019, casein, oil, silkscreen ink, gesso on wood, 32 3/8 x 32 3/8 x 1 inches (82.2 x 82.2 x 2.5 cm), Miguel Abreu Gallery, New York