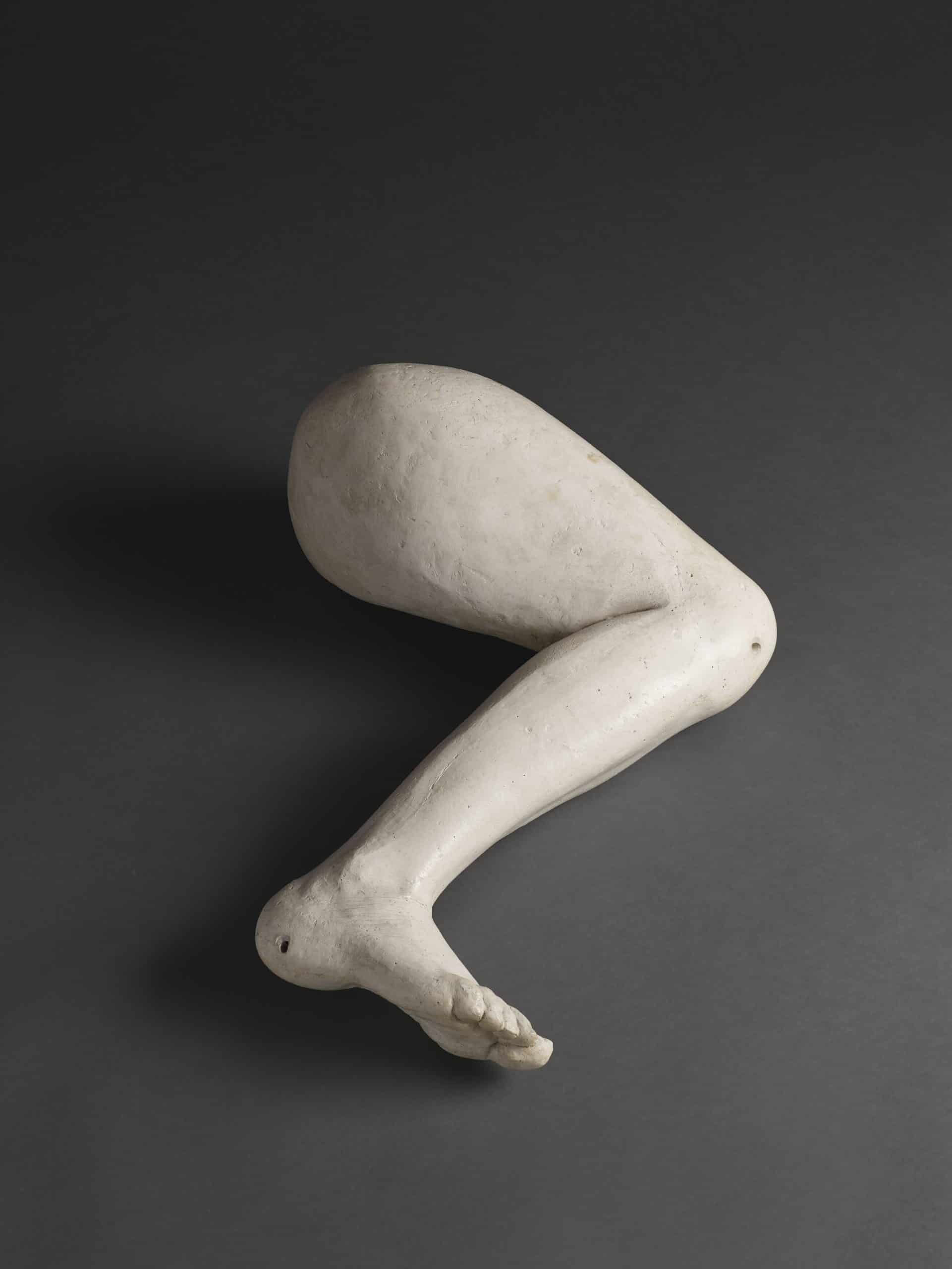

Alina Szapocznikow’s latest retrospective at Hauser & Wirth spans the last decade of the artist’s “brief but explosively inventive career”. The exhibition starts with two plaster sculptures, “Noga” (Leg) and “Sans titre” (Untitled), that depict Szapocznikow’s fragmented body. “Noga”, a casted right leg of the artist, marks Szapocznikow’s earliest use of her own physicality, whereas “Sans titre” is a continuation of her interest in exploring one’s own corporeality and its imprint through sculpture.

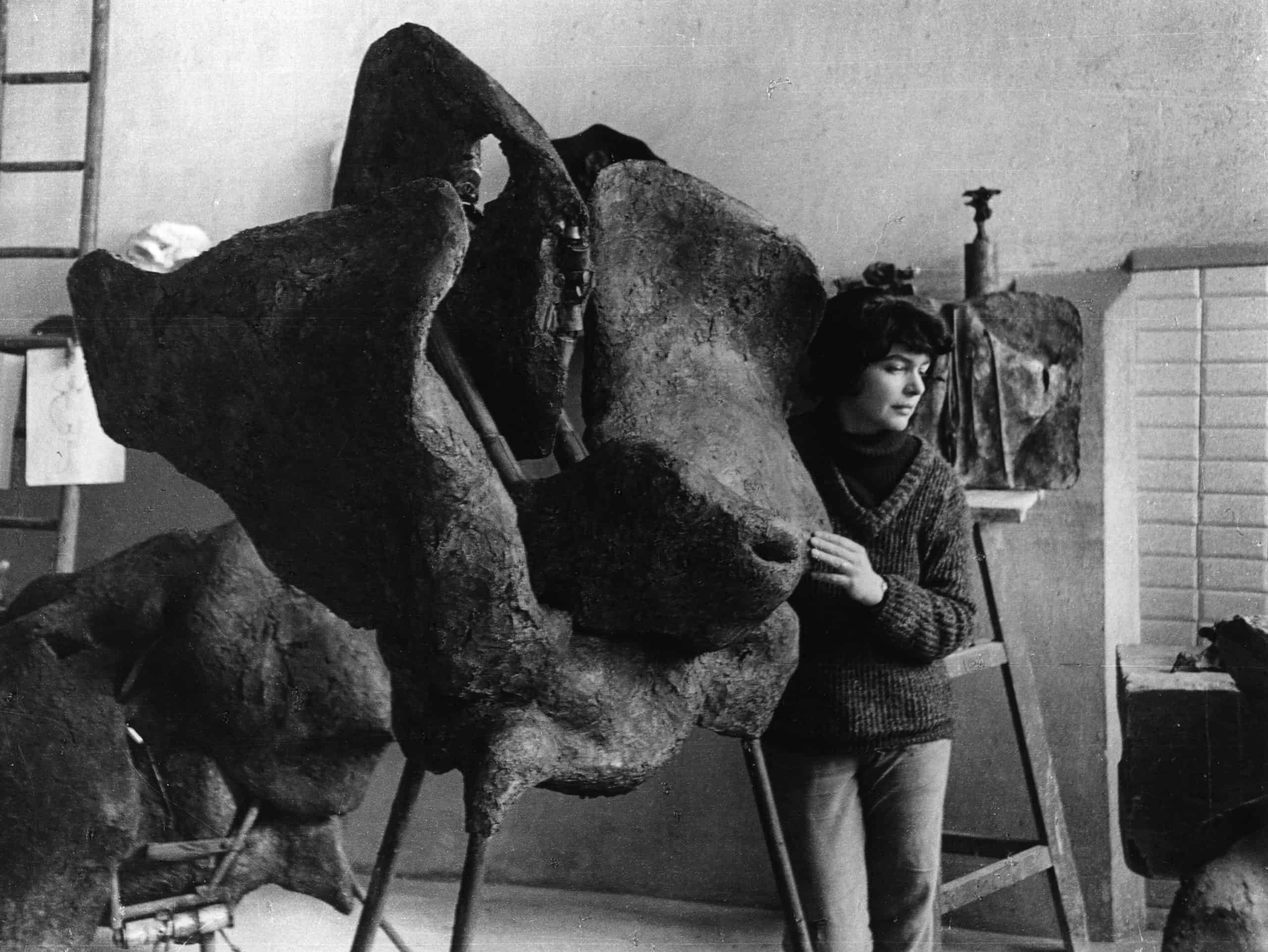

Alina Szapocznikow in her Père-Lachaise studio, Paris, FR with her work ‘Sculpture avec une roue tournante (Sculpture with a Rotating Wheel),’ 1963-1964, ca. 1963, Photographer: Władysław Sławny

Szapocznikow’s works are radical and erotic, powerful and vulnerable at the same time. They are extremely feminine and tender, delicate and fragile. They are not only full of overwhelming beauty, but also agonising pain and incomprehensible horror. It is hard, if not impossible, to think of Szapocznikow’s oeuvre without considering her past traumatic experiences, those of a Holocaust survivor, a victim of tuberculosis and breast cancer. She never really wanted to talk about what she went through. Neither to her son, nor to the public. But she found a way to digest her pain, to face it and to not let it tear her apart.

Instead of suppressing her traumatic experiences and emotions, Szapocznikow dealt with them in her art. Through sculpture, she tore apart painful memories, atrocious images, and unwelcome flashbacks. Sometimes even literally, like in “The Souvenir Series”, where she coated old, ripped apart photographs with polyester resin. In “Souvenir I”, the artist combined her photo as a child with a photograph of the body of a corpse in concentration camp pyjamas. The result is scary and disturbing, and it is hard to imagine what Szapocznikow, who spent part of her childhood in ghettos and concentration camps, saw and lived through.

Alina Szapocznikow with her work ‘Tors (Torso)’, 1966, Photographer: Marek Holzman

Alina Szapocznikow, Noga (Leg), 1962,

Plaster, 20 x 50 x 63.5 cm / 7 7/8 x 19 5/8 x 25 in

After World War II ended, artists were looking for ways to deal with what they had experienced. They wanted to preserve their feelings in order to prevent another world war from taking place. Some of them did not want to talk about it, because it was too hard, too painful and the times have changed. Others faced the issue of how to talk about the war and its cruelty. They were looking for ways to express their anger, mutilation, and suffering. They had to find new ways of expression because the old ones seem to be all wrong. Nothing could reflect their torment.

Szapocznikow never really spoke of the unspeakable and the unimaginable to her family and friends. Instead, she did so through her art. And she succeeded. Although we will never be able to imagine the atrocities of the war, Szapocznikow’s sculptures give us a glimpse of what it is like when the world is turned into a living hell, when there are corpses everywhere, fragmented, dismembered and devoid of humanity. When you cannot distinguish between the outsides and the insides, between hands and legs, when everything is turned upside down.

“To Exalt the Ephemeral: Alina Szapocznikow, 1962-1972”, exhibition view, Hauser & Wirth, London, 2020

“Of all the manifestations of the ephemeral the human body is the most vulnerable, the only source of all joy, all suffering and all truth”, Szapocznikow used to say. She celebrated the human body and its evanescent nature. One of the most important qualities present within her art is tenderness. We see it in her lamps, in her autoportraits, and even in her chewing-gum photographs, where she treated chewing-gum like any other sculptural material, with respect and caution. Szapocznikow did not think about chewing-gum as rubbish, rather, she perceived it as a valuable relic, that at the end takes the form of an abstract sculpture. She wanted us to see it just as she saw it, as something treasurable, bursting with potential. “Chew well then. Look around you. Creation lies just between dreams and daily work”. May these words guide us to a better future, where tenderness and respect are just as important and ever-present as in Szapocznikow’s works.

“To Exalt the Ephemeral: Alina Szapocznikow, 1962 – 1972”

Feb – 2 May 2020

Hauser & Wirth

“To Exalt the Ephemeral: Alina Szapocznikow, 1962-1972”, exhibition view, Hauser & Wirth, London, 2020

“To Exalt the Ephemeral: Alina Szapocznikow, 1962-1972”, exhibition view, Hauser & Wirth, London, 2020

“To Exalt the Ephemeral: Alina Szapocznikow, 1962-1972”, exhibition view, Hauser & Wirth, London, 2020