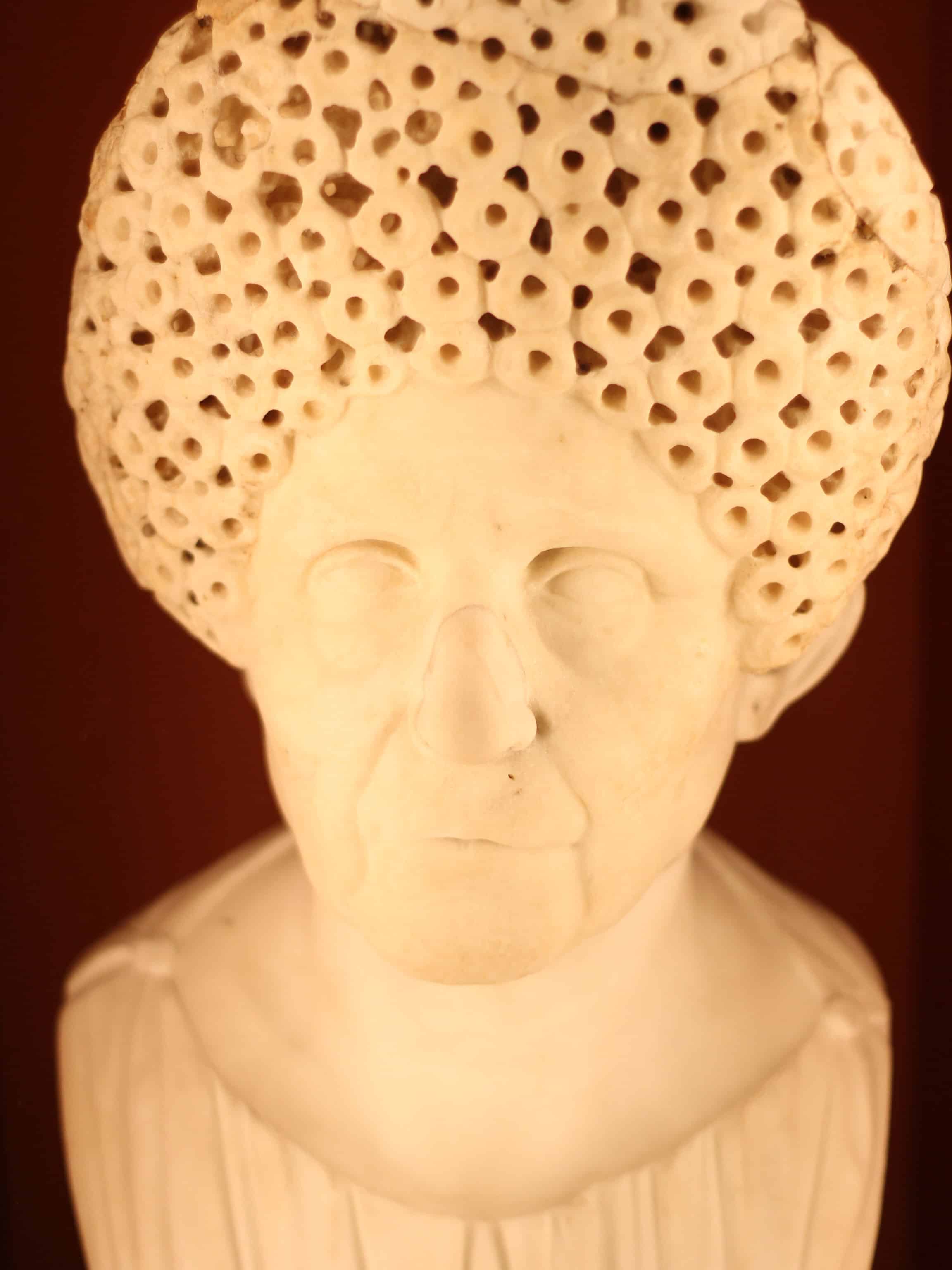

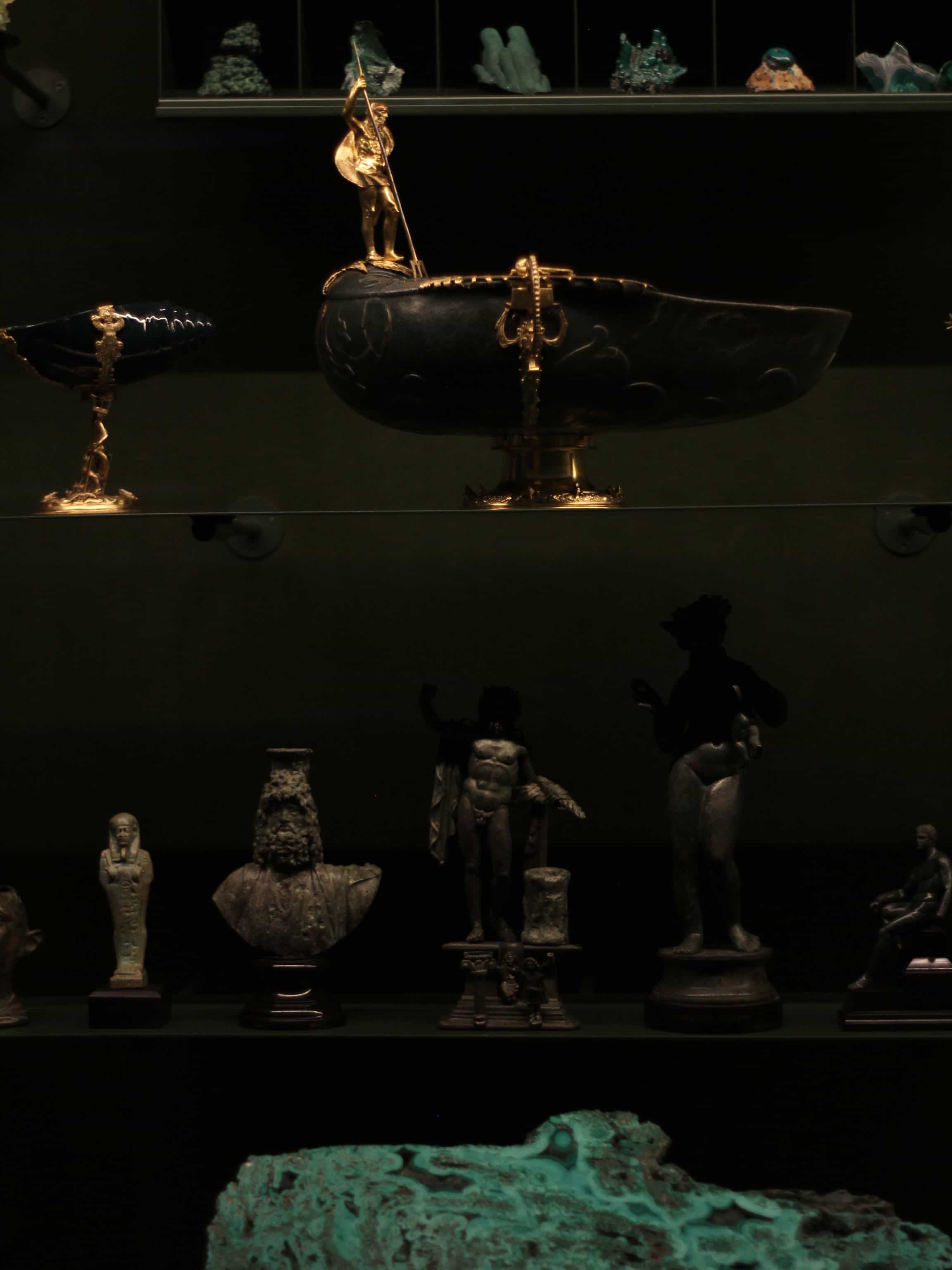

„Spitzmaus Mummy in a Coffin and Other Treasures” exhibition, photo: Dobrosława Nowak

“Il Sarcofago di Spitzmaus e altri Tesori” („Spitzmaus Mummy in a Coffin and Other Treasures”) is an exhibition project conceived by the director Wes Anderson and the designer, illustrator, writer, as well as Anderson’s wife – Juman Malouf. The display is said to ‘challenge the traditional canons that define museum institutions’. As innovative as it sounds, the space with a Wunderkammer-like arrangement was inspired by Ambras Castle in Innsbruck, a 16th-century palace designed to house the collections of Archduke Ferdinand II of Habsburg and his wife Philippine Welser. What is so revolutionary about it then? The part that breaks new ground is the authors’ idea to juxtapose 537 natural findings, artworks and artefacts from over 5000 years of human existence (time span that extends from 3,000 BC to 2018) in an order unheard of before; to showcase them deliberately non-academically (unconcerned with time periods and chronological accuracy), and to emphasize the interdisciplinary approach. Some works are grouped: green objects, wooden objects, children’s’ portraits, miniatures, animals, timepieces, boxes, portraits of noblemen and common people, natural subjects, meteorites and animals, presented as scientific exhibits or artistic depictions. The curatorial effort is aimed at ‘taking the form of a reflection on the motivations that guide the act of collecting and on the ways in which a collection is kept, presented and lived’. Despite this, the impression that the exhibition makes is emanating with a rather light-hearted atmosphere. The title of the exhibition refers to one of the exhibits, the coffin of a Spitzmaus, an Egyptian wooden box with a mummified shrew from the 4th century BC. Juman Malouf fondly draws it many times, and it seems clear who stands behind the idea of this mascot becoming a leitmotiv of the exhibition.

„Spitzmaus Mummy in a Coffin and Other Treasures” exhibition, photo: Dobrosława Nowak

More about the spatial frameup of objects tells Wes Anderson himself in the friendly introduction to the exhibition’s catalogue: “We situate the seventeenth-century emeralds in a confined space opposite the bright green costume from a 1078 production of Hedda Gabler in order to call attention to the molecular similarities between hexagonal crystal and Shantung silk; we place the painting of a seven-year-old falconer (Emperor Charles V) next to the portrait of a four-year-old dog owner (Emperor Ferdinand II) in order to emphasize the evolution of natural gesso; a suitcase for the storage of the war-robe of a Korean prince goes next to a case for the crown of Rudolf II, because both were so clearly shaped and formed by the introduction of the hinge“. A few sentences further he writes that even for the both of the greatest museum’s specialists, these inner references were pretty difficult to discover, and, in a sense, he admits curatorial defeat, at the same time emphasizing the importance of experimenting with creative tactics.

For this cutting-edge exhibition, Fondazione Prada collaborates with the Kunsthistorisches Museum (its 12 collections) and its twin museum Naturhistorisches Museum (11 departments), Vienna. This is probably one of the most beautiful outcomes of the whole experience. When two influential institutions are able to join forces and carry out costly and heavy, fragile operations on objects, (including transport, display, etc. – sometimes art is also about the down-to-earth issues), to create such visually smooth circumstances is already a win. By challenging the traditional museum canons, artists and galleries propose new relations between the institutions and their collections, as well as between professional figures and their public.

The inaugural exhibit of the arrangement conceived by Wes Anderson and Juman Malouf was already presented in Vienna in 2018. Now it has been moved to Fondazione Prada in Milan. The current display space covers a larger area and has a greater number of exhibits. Alongside the exhibition, the project is completed by an artist’s book published by Fondazione Prada. The publication takes the form of a box including drawings, reproductions and other various materials, and elaborates on the idea of the portable museum and the personal collection, referring to Marcel Duchamp’s Boîte en-valise as its inspiration.

„Spitzmaus Mummy in a Coffin and Other Treasures” exhibition, photo: Dobrosława Nowak

Last year, the exhibition in Vienna was reviewed by Cody Delistraty for the New York Times with these words: ‘The desire to flatten and redefine works that were already bursting with their own histories made the show feel like the <Accidentally Wes Anderson> Instagram account: It had Mr. Anderson’s surface-level aesthetic, but none of the underlying narrative or emotion of his movies‘.

What she says is not far from the truth. Anderson’s visual style is undeniably noticeable at the exhibition (just as it is at the whole Fondazione Prada, including ‘Luce Bar’ designed by him in 2015, located at the very entrance of the gallery). At the same time, both inventively and senselessly juxtaposed works sadly remain on the surface level of the matter. Something didn’t work as it was supposed to, some guideline is missing. To justify the authors slightly, it’s worth adding that there is no one as precise and willing to put an unbelievable quantity of effort into his creation as Wes Anderson, but probably, after digging through 4.5 million works in both museums (Cody Delistraty adds that the artist couple isn’t fluent in German either), they stuck with creating the exhibition by following the visual temptations of colour, material, and size of the objects. ‘Onscreen aesthetic is all about creating narratives and moods — of yearning, of melancholy, of passion. Art curation is a fundamentally different pursuit. Unlike a director moving actors around a set, a museum curator cannot dictate how the works will make a viewer feel’ – adds journalist.

As Wes Anderson explains at the beginning of the exhibition catalogue: ‘Juman Malouf and I jumped at Jasper Sharp’s offer to follow in the footsteps of the wonderful Ed Ruscha and Edmund de Waal, and curate our own version of the greatest hits of the Vienna Kunsthistorische because: a.) we love the museum and have been visiting it on regular basis since we met over a decade ago; b.) we were honoured to be asked and eager to do anything we could to support that magnificent institution; and c.) we thought it was going to be easy’.

Putting aside the accuracy of the concept and curatorial performance, we will find a whole bunch of truly phenomenal objects at the exhibition. Some of them are notable works of art, as is a painting of Salome carrying the head of John the Baptist on a platter (Bernardino, 1532), others are curiosities like an emerald, a cigarette case, feathers, bowls.

We are sinking into the gallery space among intensely-orange curtains hung around the ‘Podium’. The exhibition was aimed at creating a setting inspired by the Italian garden, with the presence of elements evoking hedges and allegorical pavilions typical of a Renaissance garden. The overall visual impression is somehow exotic, and at the same time, it looks as if we were inside a huge toy.

Edited by: Paulina Prońko

Il Sarcofago di Spitzmaus e altri Tesori

Fondazione Prada

20.09.2019-13.01.2020

„Spitzmaus Mummy in a Coffin and Other Treasures” exhibition, photo: Dobrosława Nowak