Teresa Tyszkiewicz,Cotton Wool, 1981, black and white photo, courtesy of the artist and Muzeum Sztuki in Łódź

Tyszkiewicz

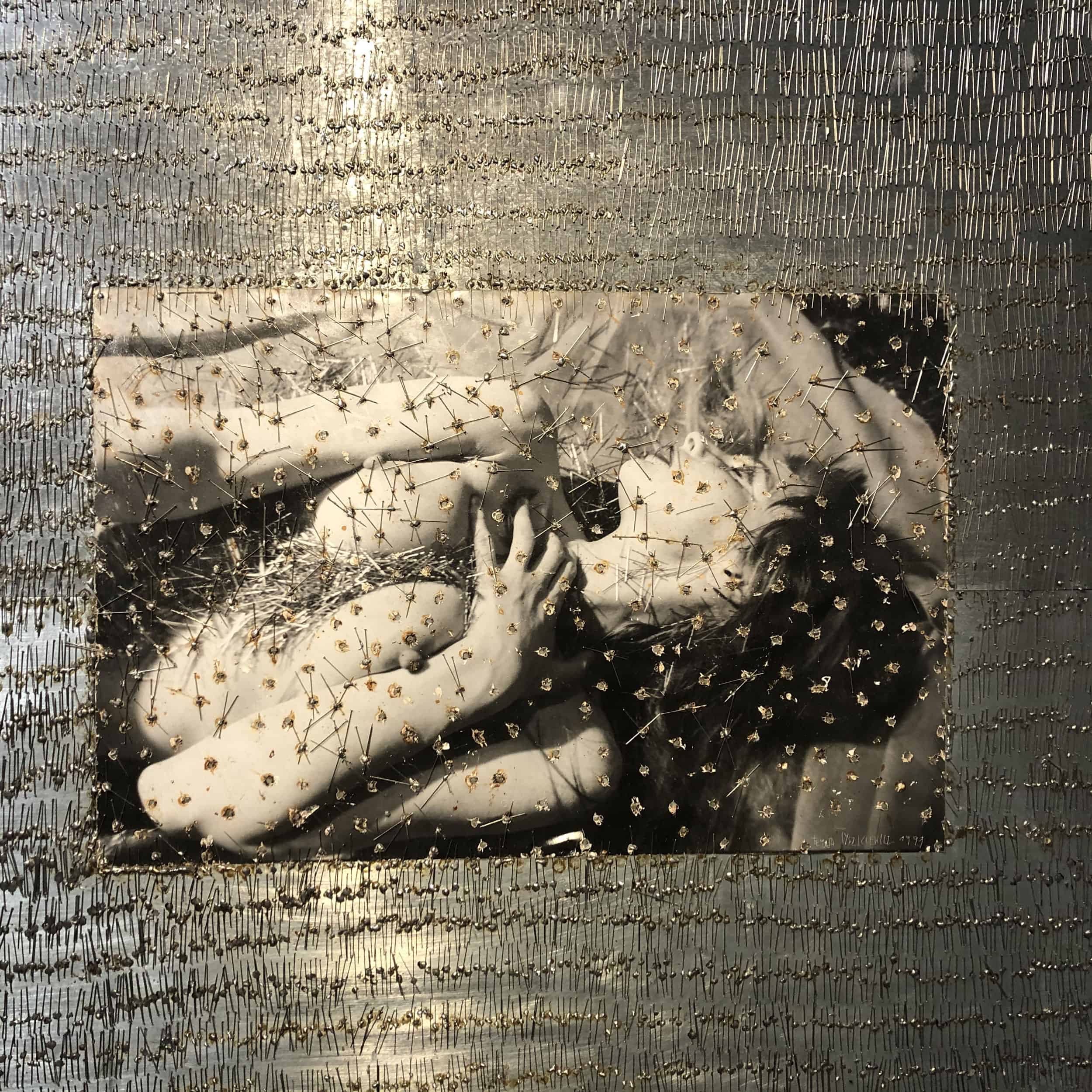

How does one examine his own physicality and its limits? Is it by measuring and observing what extreme experiences lead us to? Is it by confronting the matter that surrounds us? Should we take our body as a point of reference or treat the surrounding reality as such, and our own body and feelings as the measure? Will that which is subjective, through having the same traits shared with others, become objective? A pin piercing fingertip makes the blood flow out of it, but to each and every person that feeling will be different. The image of a puncture wound is common, but the emotional scale of the experience itself is not. An image evokes memories and memories stir up compassion. This loneliness and individuality, however — and thus the infinite plurality of experience — make this subject to be constantly explored by artists. I recently had an opportunity to see the monographic exhibition by Teresa Tyszkiewicz (1953-2020) at Muzeum Sztuki in Łódź. The way the artist explored matter (the matter that surrounds her, but also body as matter) is the way in which she examined her physicality.

Teresa Tyszkiewicz, Wywloka, 1980, colored photo, courtesy of the artist and Muzeum Sztuki in Łódź

Matter of nature

Tyszkiewicz used different media. She produced short films, photographs, performances, objects and paintings. The range of elements she used on this occasion was very narrow. The main tool was her body, which she juxtaposed/confronted with individual, selected objects: grains, earth, plants, feathers, cotton, wool or pins. The body, as Tyszkiewicz recalled, “[…] is necessary. It is a base, a ‘home’ that protects my personality. It plays the role of a “link” between reality and imagination. In my films I can’t really find another tool, than my physical self, because I always want to outline the idea with myself.” The direct and physical contact then was an irreversible element of action. It brought the body to a matter that coincides with the matter surrounding us. What is more, the hand, the naked body, and even human creations — including works created by the artist, which we can spot buried in the grains (“Grain” 1980) in the same way as the body — all serve as an integral part of nature. Animate and inanimate objects are all part of a larger whole. In this way, Tyszkiewicz has stressed the original connection with the earth. “She has shown the need for establishing a relationship with the matter as a specific self-analysis. For Tyszkiewicz the return to the source is an attempt at self-knowledge, at examining one’s own limits, a return to the nature of the human body — the female body — inseparably linked to the primeval cycle of life, and going further, tied to the cult of Mother Earth“, says Zofia Machnicka, the curator of the exhibition in Łódź. The earth’s fertility, grain, cycle of life, fragility, sexuality, organicity, pleasure and pain — all of this is merged in the works by Tyszkiewicz. It is our pain and our body, our blood and entrails, our fragility and our strength. It is nature.

_Teresa Tyszkiewicz, courtesy of the artist and Muzeum Sztuki in Łódź

Commonality of the individual experience

The above rituals are like mystical experiences and in them have something of shamanism. Repeated gestures, like those in a mantra, are the way to initiation. “My body is a medium, the source and creation of the problem“, Teresa Tyszkiewicz said. What follows meditation and tantric activities is a way out of singularity and uniqueness in the direction of community. Her personal struggles and needs are shared by other women. This is the affirmation of sexual energy, self-awareness, attractiveness, and sensuality that the artist has confronted with everyday life, and which she transformed into a creative material. At the before-mentioned exhibition a new film was presented, which the artist had assembled especially for this occasion – “ARTA” (1984-85 / 2019). “In it, birth and motherhood are depicted. We see pasta being grabbed voraciously by the artist and spread on the body between her legs and her breasts“, says Zofia Machnicka. She presses it into bags hanging on her body and, with the same devoutness, presses it into the holes in the hanging canvas, which is then pricked with pins. The finished “pin” image is the background for a lying baby. “Female physiology has been stripped from all aestheticism. The ambiguity of female physicality is brutally and naturalistically shown in the film” – Machnicka added. In a different work, naturalism is combined with the aggressive action of screwing a large screw/metal corkscrew into a table: the handle of the corkscrew has been covered with rabbit fur (fur with the animal’s head and legs), and the artist, breathing heavily and taking on erotic poses, tires herself more and more while tightening the screw. The sound is mixed with voices from other videos and in the end creates an acoustic setting for the display (sound mixture of tiredness, struggle, pain and pleasure). Machnicka pointed that ‘For suffering, brutality, loathing and physiology are inextricably linked to the experience.’

_Teresa Tyszkiewicz, courtesy of the artist and Muzeum Sztuki in Łódź (1)

The process and the experiencing

Indeed, looking at Teresa Tyszkiewicz’s work, one sees immediately how important the process of investigation, development, and thus experimentation with matter is. In Tyszkiewicz words, “The process is an experience. It is an action. (…) While working I feel like a point, a prick of my pin.” Film and performance were the media that the artist was particularly eager to use in the early period of her work. At first created together with her husband, since the 1980s they were made by the artist herself. From the beginning it was a record of experience. Her works are the process of immersing oneself in the grains; touching, mixing, reaching, brushing flowers; rubbing against vegetable tubers. It is an interaction that takes place in time and its effect and intensity depends on the sensitivity to reality surrounding her (but also us — the viewers).

For the artist, the experience often resulted from living and working through extreme activities. And so in the 1980’s she used cotton wool and a pin confronting them with her body. From the cotton wool wrapped around her she made a cocoon, a safe layer (just like the aforementioned rabbit fur covering the tool of violence). Here, the pins became the instrument of autoaggression. Scattered on her face, sticking to the naked body they pricked and wounded. They were also a carrier of action. The artist not only used them on herself but also started piercing the paper and canvas. With time, large compositions — Tyszkiewicz favourite format was 300 x 150cm canvas — were covered by pin next to a pin next to a pin. Hammered in by hand, they injured the author, deformed the flat and smooth images creating an extremely material and organic form. Bulges — like scars — were a sign of bold violence, an external force deforming the initial state. These “scars” — the place where the pins pass under the painting’s surface — were additionally emphasized by highlighting them with a red or a gold line. As Machnicka says: “The abstract composition tempts and hypnotizes with its appearance from afar, with the pinheads’ reflection, sometimes evoking the shape of a vagina – it attracts with its eroticism. On the other hand, its aggressiveness repels and causes subcutaneous pain. We are dealing with the motif of “Vagina dentata”, where desire is inseparably joined by fear.”

Watching the works by Teresa Tyszkiewicz, it is hard not to ask a question of what constitutes us: what are the limits of our physicality? By perceiving seemingly simple elements of the environment, the most basic gestures, Teresa Tyszkiewicz shows new links and values. There are no symbols and metaphors in it. There is pure matter. For Tyszkiewicz confronting it was a way to measure her physicality and corporeality. By examining herself, however, she also sensitized us to experiencing. The artist died in January 2020 while preparing for her exhibition in Łódź.

Teresa Tyszkiewicz, Les yeux _ Oczy, 1984, black and white photo, courtesy of the artist and Muzeum Sztuki in Łódź

Teresa Tyszkiewicz, Épinglé, rouge et noire, 1985, courtesy of the artist and Muzeum Sztuki in Łódź