Closure or restricted access to cultural institutions, including museums, offer a great opportunity for digging deeper into the engagement strategy, viewer participation and museums’ objectives that determine their programmes. The present time seems even more suitable for reflection if we consider the fact that this year marks the 90th anniversary of the foundation of one of the leading contemporary art museums – the Muzeum Sztuki in Łódź. On the 15th of February 1931, the “a.r.” group donated a collection of artworks created by a then up-and-coming generation of artists. They were the ones that contributed to the establishment of the modern museum, not its director or local and national authorities. At first glance, the gesture seems at variance with the dismissal of traditional and antediluvian institutions professed by artists across generations. Especially if the gesture is performed by some avant-garde artists associated typically by the general public with the disruption and demolition of museums – like the Dadaism. However, their actions did not occur in a vacuum. From 1912 until the late 1940s, the artists’ active involvement in innovative museum projects was a part of the public discourse and numerous experiments in the art world.

Viewer’s role in the Avant-Garde Museum

To a large extent, this phenomenon (especially in Russia and Germany) was closely related to the shift in the perception of the viewer in the process of institutionalisation. The viewer’s role as a consumer shifted towards a participant who is able to experiment. They are active and have a real impact. At that time, artists from Russia, Poland, Germany, and the USA were united to expunge the popular notion that interaction with art boils down to a purely aesthetic experience. This has brought another frequently invoked argument that is a complete disregard for the educational function of museums.

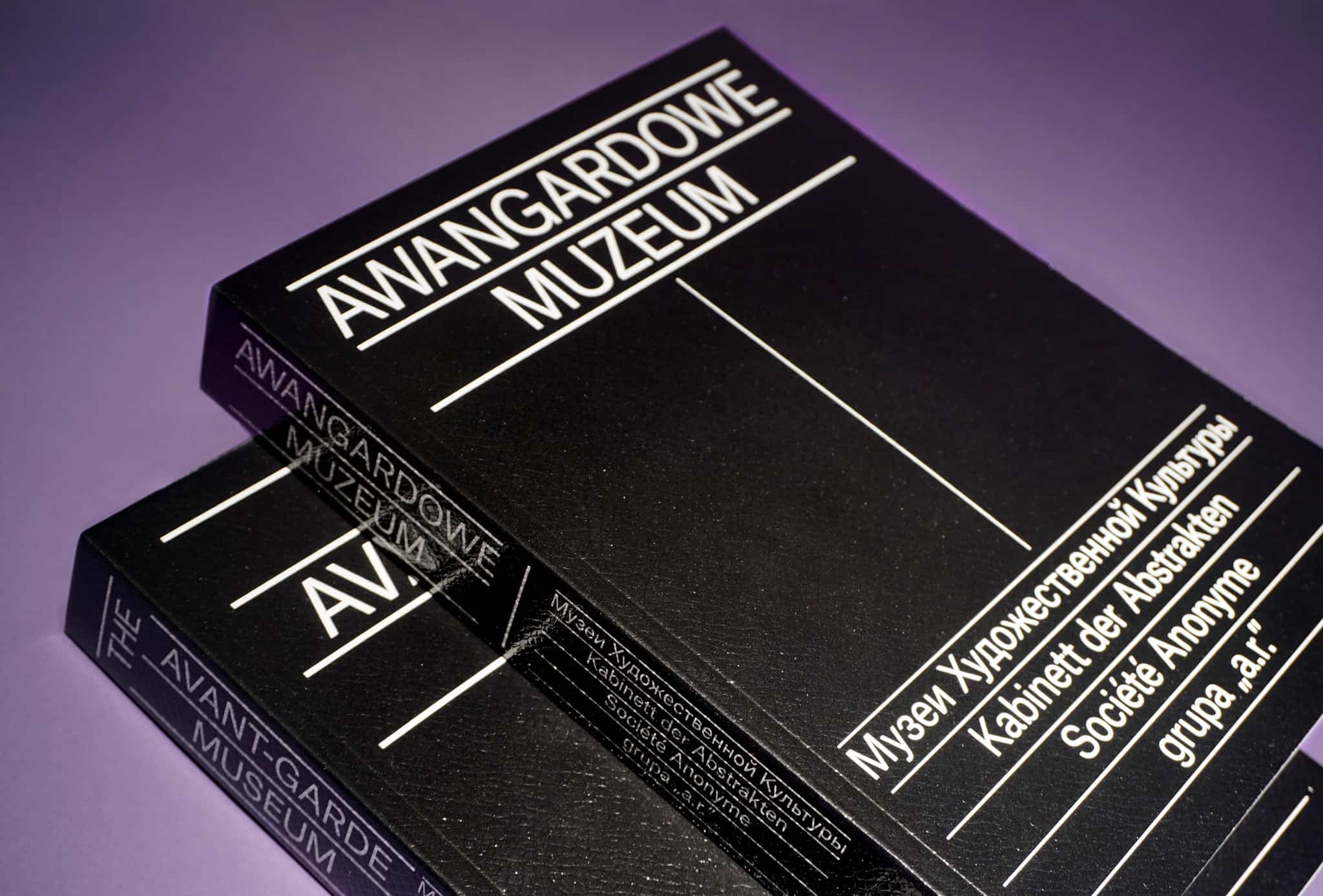

How would an avant-garde museum look like? The extensive volume of The Avant-Garde Museum, which was published a month ago by the Muzeum Sztuki in Łódź, offers the answer to this question. The publication consists of materials devoted to four avant-garde groups associated with the network of Museums of Artistic Culture in Russia, Kabinett der Abstrakten in Germany, Société Anonyme Inc. in the USA, and the “a.r.” group in Łódź.

Thus, Aleksander Rodchenko viewed the space as a laboratory; Wilhelm Bode advocated for isolation of a single artwork situated in its “original” space, which meant home; El Lissitzky and Sophie Lissitzky-Küppers went a step further by proclaiming that the space itself had to be art. The so-called “demonstration room” by Lissitzky in Hannover and Dresden illustrated this postulate.

In the essay “Futurist Museology” published in the above-mentioned book, Maria Gough cites one of the most radical statements in this matter made by Rodchenko, who envisioned his Museum of Experimental Technique (established on the basis of a restructured experimental section of the Museum of Artistic Culture) as cool as a morgue and as dry as a mathematical formula. The entire art practice is one great experiment. In this context, a museum is supposed to provide a living space for experimentation; a place where new ideas are born; a point of departure for a series of ingenious creative endeavours and critical thinking. Following the thought of Brian O’Doherty, Gough states that the aim of museums was to denounce the common belief that “art can be absorbed effortlessly.” Taking into account the statement above and other postulates of the Russian futurists and constructivists, we can surmise that work and effort are quintessential. Without any drive, any mental or physical toil, the resonance of art and culture will never reach its full potential. How does the resonance manifest itself? Well, by creating reality! Until one lives through this “moment”, all other experiences are deficient and superficial; hence, they will be merely aesthetic.

Hungry for more?The institutional structure is meant to ensure the full spectrum of this experience. According to Vladimir Tatlin and Sofia Dymshits-Tolstaya, the erected museum is designed as an entire complex consisting of lecture halls, workshop rooms, and – what I find the most fascinating and worth considering – art studios! Can you imagine a contemporary museum, which apart from exhibition spaces, opens the studios available to various artists in rotation to foster integration, debate, and common development of ideas and activities? Today, one hundred years later, viewers are thrilled about “a bold move” of a public institution to run an Instagram account where they post photographs of selected studios, or to put an artist in charge of “designing” a fraction of its interior, e.g. a coffee shop. Would not they say that in the light of the early 20th-century postulates these kinds of projects seem uninspired and safe, maintaining the status quo of the division between here (museum) and there (artist)? Where are audacious pursuits befitting our times and reshaping the creative community, advocating for it while abolishing these divisions? Where is the fight for the culture for everyone?

Needs and expectations

In The Avant-Garde Museum, in her essay “Sensational Pedagogy: El Lissitzky’s Demonstration Rooms as Precursors to the Contemporary Museum Experience.”, Sandra Karina Löschke examines El Lissitzky’s non-artistic experience with popular culture. The author makes an interesting observation, which we might have failed to heed, that “the interests and ambitions of a wider audience often deviated from the assumptions made about them.” They differed then and continue to diverge. In the early 20th century, Lissitzky tried to channel the needs of the audience to shape exhibition rooms actively. It already aimed to cross the line of the purely academic interaction between museum and viewer in a form of, for instance, guided tours. (Initially, Alexander Dorner, the former director of the Provinzialmuseum in Hanover, inclined towards this solution before he got acquainted with Lissitzky’s “demonstration room” in Dresden. Then he invited him to cooperate on such a project in Hanover). Though often fascinating and knowledge-infused, these tours are still a form of the passive walk through the exhibits that uphold a teacher-student paradigm. Unfortunately, in today’s world, they have also been replaced with videos on Facebook. The audience watches the hundredth tour in a row glued to their phones while a torrent of app notifications flashes on screens.

I cannot help but wonder how we lost a need to bridge the gap between an institution and viewers? Where is the need to develop and nurture awareness and sensibility among the audience instead of reducing them to a statistical element to measure an uptick in a number of visitors, clicks, and numerical values? Otherwise, the audience only serves to increase institutions’ credibility in the eyes of those who write big checks or give a government grant. Maybe, the issue of active shaping of the exhibition, the role of the viewer as a curator and active critic, should be raised again. I hope that The Avant-Garde Museum publication will reinvigorate our need to seek new form for the idea of a museum and its audience. In my opinion, the pandemic shed light on the crisis that has long affected museums. Instagram quizzes and flash posts of institutions are not enough to capture viewers’ attention for good and make culture an integral part of their lives.

In February 1931 the International Collection of Modern Art of the “a.r.” group was opened to the public at the J. and K. Bartoszewicz City Museum of History and Art. The collection was to become the foundation of the Muzeum Sztuki in Łódź. In 2016, on the occasion of the 85th anniversary of this event, we have the pleasure to talk to the Museum’s director – Jarosław Suchan.

How we can change the future

This publication is even more fascinating if we consider translating the concepts of engagement and popularisation, which are discussed, for instance, by El Lissitzky much broader. These ideas could lay foundations for rethinking educational programmes and popularisation of art as well as the perception of printed publication (such as magazines), which are particularly close to my heart. This book is a lesson for me as well. The media, as the popular platform with an enormous reach, is another and sometimes wider/farther-reaching road. They are the outlet for debate, sparking and encouraging one’s need to experience art. Moreover, media increase citizens’ awareness and engagement not only in participating in the “narrow” sphere of so-called “high art” but more broadly, through culture, encourage them into a conscious being in a society (in which culture plays a key role). How important is that nowadays, during the lockdown, when art permeates and fills the void of social contact in our world. Mass and high culture are screened on TV, computers, and phones; meanwhile, art goes to the streets and filters our perception of civic and political movements through artistic activism. The images are directed at the wider audience. In the spirit of the avant-garde, I would postulate our return to the one-hundred-year thought in search of untapped potential. We might have missed something that could prevent us from making mistakes at the dawn of the new era. Mistakes happen in various areas of social life. We seem to have come to a collective realization that both the virus and the year we left behind have a single advantage. They have brought us to a standstill amidst all the frenzy, so we can finally take a deep breath and reevaluate our core values. It also means more time for our loved ones and ourselves. Hitting a button to pause an action movie – our lives – is the perfect time to redefine the model of participation in society. Also, and perhaps above all, participation in broadly understood culture. We might investigate it from either the standpoint of an insider and take the elements determining our professional and expert approach to the art and art world as such. As well as an outsider who is a viewer.

Does not the world of art and culture seem like an ancient “Khôra”? A place and yet not a place that is both tangible and intangible; egalitarian and elitist; available to everyone and just to itself; the space which is closed; the space beyond that and in-between. For a century, art and culture have made a quantum leap in terms of global “modernisation”. Gorging enthusiastically on a cake with a familiar taste of modernism and postmodernism, we failed to notice that there is no cherry on top. The avant-garde experiment blew up in our faces like a bunch of rainbow sprinkles, leaving us blindsided, covered in smoke and grime. Now it is time to analyse time-lapse footage; even if it is conducted only on our phone screens. We mastered a skill to examine and understand the past better to shape the present (although, used lately in an extremely short-sighted and populist manner). Now, it’s time for another step forward. To paraphrase Joseph Ganter from 1930, an editor of “Das Neuer Frankfurt”, “It’s time to provide viewers with the cultural capital that could change the future.”

Return to the homepage