Andrzej Wróblewski and Božena Plevnik (1933–99), later director of the City Gallery in Ljubljana, Slovenia, photo: Barbara Majewska, © Andrzej Wróblewski Foundation

Perhaps the harshest review of the “Po Prostu” Salon came from Barbara Majewska, a young graduate of art history and debuting critic of Przegląd Kulturalny. Incidentally, just a few weeks later, Majewska traveled to Yugoslavia with Wróblewski. The artist makes reference to her in a diary entry from September 22: “Majewska’s re[view] P[rzegląd] K[ulturalny]”; the day before he writes: “Gomułka and other revivalists.” According to Majewska, while other artists—Wróblewski’s peers, Włodzimierz Kunz, and Witold Damasiewicz—“did not show works that would provide arguments for a negative assessment,” created worlds brimming with “suggestive mood, a wide range of emotions and knowledge about human affairs,” Wróblewski certainly did not. “The world [in his] paintings should … rather be pieced together and read as individual elements, none of his works is convincing as a separate entity.”1 Majewska points to the “literary concept” of his paintings (especially The Queue Continues) “built around pessimistic reflections concerning life [which] burdens the formally shallow paintings, and becomes a pretentious and artistically unjustified addition,” “too strong an attachment to the actual appearance of objects, hindering the formation of distinctive forms, truly artistic forms—meaningful forms, which are the equivalent of painting. … The same applies to color that appears on canvas—often unjustified, vague.” To sum up: according to Majewska, Wróblewski shows a lack of consistency in determining the overarching goal of a given painting and a lack of his own incorporation of selected means and forms, thus often achieving caricature and cliché. The next sentence in the review carries a different weight, as the author shares one of the most accurate, precise and penetrating diagnoses about Wróblewski’s painting, similar to his own view expressed in 1948: “The difference between a metal file and a painting is that a painting is more versatile in its use. It can convey a revolution through abstraction.”2 Majewska writes: “The artist does not condone painting’s acquiescence in the face of social problems and makes them a source of conflict in his paintings.” And this is the very essence of Wróblewski’s art that leads us through his subsequent ideological projects—from the abstraction that organizes the new world order (Exhibition of Modern Art, 1948) through the programs of the Self-Educational Team (e.g. the concept of “social contrasts” and the anti-war program, 1949), searching for one’s own socially engaged realism in opposition to academic Socialist Realism, right up to the thaw period studies of the social condition, created in opposition to “[the] thoughtlessness of the thaw period,” as Wróblewski put in a letter to Andrzej Wajda.3 Let us focus on this letter, most likely written in 1956. It is likely the only evidence of the artist’s comments on this particular sociopolitical moment. In it, Wróblewski focuses on the MULTIARTISTIC exhibition project, created by the MULTIARTISTIC GROUP of artists and the MULTIARTISTIC EXHIBITION COMMITTEE set up at the Council of Culture. This can be understood as the artist’s proposal for another artistic reform within his work. The first in the series of planned exhibitions—as Wróblewski writes—“depicts the responsibility we should all take for those who died or grew complacent in the name of socialism. The exhibition will oppose the thoughtlessness of the ‘thaw’ period and the loss of all purpose in life bar food and entertainment.”4 It is a strong statement directed not only against artists committed to Socialist Realism, but also those who naïvely followed the false promises of democratization and of the thaw period. It seems that Wróblewski is equally disappointed both with the thaw and Socialist Realism.

![(The Presidium), [Group Scene no. 713] / (Prezydium), [Scena zbiorowa nr 713]; undated; ink, paper; 29.2 × 42 cm; private collection, © Andrzej Wróblewski Foundation](https://contemporarylynx.co.uk//wp-content/uploads/2020/10/andrzej-Wróblewski-1.jpg)

(The Presidium), [Group Scene no. 713] / (Prezydium), [Scena zbiorowa nr 713]; undated; ink, paper; 29.2 × 42 cm; private collection, © Andrzej Wróblewski Foundation

On October 20, Wróblewski receives a telegram from an employee of the Polish Department for International Cooperation with a request to mail two photographs. The night before, Soviet troops stationed in Pomerania and Lower Silesia begin their march to Warsaw, and are finally stopped by factory workers in Żerań. At a time when political castling was underway in the atmosphere of uneasy tension, the goal of which was Gomułka acquiring the highest office in the country, Wróblewski and Majewska are preparing for a three-week delegation to Yugoslavia as art critics and experienced reviewers (it is worth noting that in 1956, Wróblewski published one article in the press, and five in the previous year). It is hard to believe that on the day of receiving the telegram preparations for the trip were not already advanced, since on October 13 Wróblewski posts his ID card, probably in order to receive a passport. However, did the invitation come during the exhibition at the “Po Prostu” Salon or was it much earlier? Were Wróblewski’s participation, and his presence on the artistic stage of the capital, the direct reason for the invitation? There is no unequivocal answer to these questions. Wróblewski’s diary provides some scarce evidence: it includes information that on September 13, the artist goes to Warsaw for this purpose (“WARSAW in connection with Yugosla[via]”). Were Oberländer and the editors of the weekly “Po Prostu,” whose September issue included reproductions of works from the exhibition, responsible for the invitation? Perhaps Mieczysław Porębski supported Wróblewski as candidate for the trip—he was one of the co-organizers and commissioners of the Exhibition of Modern Art in Kraków. Living in Warsaw since the 1950s, then the editor of Artistic Review and lecturer at the Academy of Fine Arts, from September 10–14, Porębski represented Polish art critics (together with Juliusz Starzyński, director of the State Institute of Art of the Polish Academy of Sciences in Warsaw) at the 8th General Assembly of The AICA Art Critics Association in Dubrovnik. As one of the reports on the activities of the Polish embassy in Belgrade indicates, Porębski and Starzyński established international contacts with critics, exhibition commissioners, and artists during the AICI congress. Perhaps they had the decisive voice in identifying delegates for the cultural exchange to prepare for the traveling exhibition of Polish art planned for the following year.

(Throne) / (Tron); undated; gouache, paper; 29.5 × 42 cm; private collection, © Andrzej Wróblewski Foundation

Recently, there has been some interest amongst the local creative environment in Polish painting from the most recent period—we read in the report—proof of this was the Yugoslavian proposition to display in Yugoslavia an exhibition of contemporary Polish painting. Since this did not happen this year, it would be right to consider the possibility of organizing it in 1957. In the autumn, exhibitions will resume in painting salons, and therefore the exchange of art critics provided for in the cultural exchange plans for this year will be beneficial.5

In mid-October, both Wróblewski’s preparations for departure and the political turmoil were in full swing. The Party’s Political Bureau, or its governing body, approved the plan of changes and dismantling of existing structures (October 13). The latter was to be discussed at the 8th Plenum of the Central Committee planned to take place six days later. The party faction of pro-Soviet conservatives, in the face of diminishing influence, a weakening position and upcoming radical changes among those in power, alerted the Kremlin, and its leaders called the entire Politburo to Moscow. Gomułka did not go to Moscow. When the Soviet army, supported by Polish troops, moved toward the capital, the agitation reached the army. On the eve of the decision-making plenum, workers were given weapons, and strategic streets and buildings were patrolled and protected. On October 19, at dawn, the Soviet delegation headed by Khrushchev and the generals landed in Warsaw. While the Polish-Soviet negotiations were underway at Belweder, over five thousand supporters rallied for Gomułka at the Warsaw Polytechnic, with the participation of workers from the capital, Nowa Huta, and Kraków’s universities. The next morning, the official announcement heralded the end of talks and the suspension of the Soviet army movements, while in the evening a second rally was held at the Polytechnic with radical speeches by Eligiusz Lasota, then editor-in-chief of Po Prostu, and Lechosław Goździk, secretary of the FSO, on democracy and sovereignty. Gomułka was seen as a great hope for the reconstruction of the depreciated values of socialism, and each of the social groups held different beliefs: “The intelligentsia believed that the new party leadership would retain freedom of expression; agricultural workers—that it would guarantee private ownership of the land; laborers—that it would give them the right to organize in workers councils and provide better living conditions, and the party apparatus —that it would maintain its “leadership” role.”6 Three days after taking the office of First Secretary, at Plac Defilad in Warsaw (October 21), Gomułka addressed a crowd of 400,000 waiting for liberalization and civil liberties. However, he did not declare that the Soviet army would leave Poland. The army remained, and the previous day, the first Soviet intervention took place in Hungary.

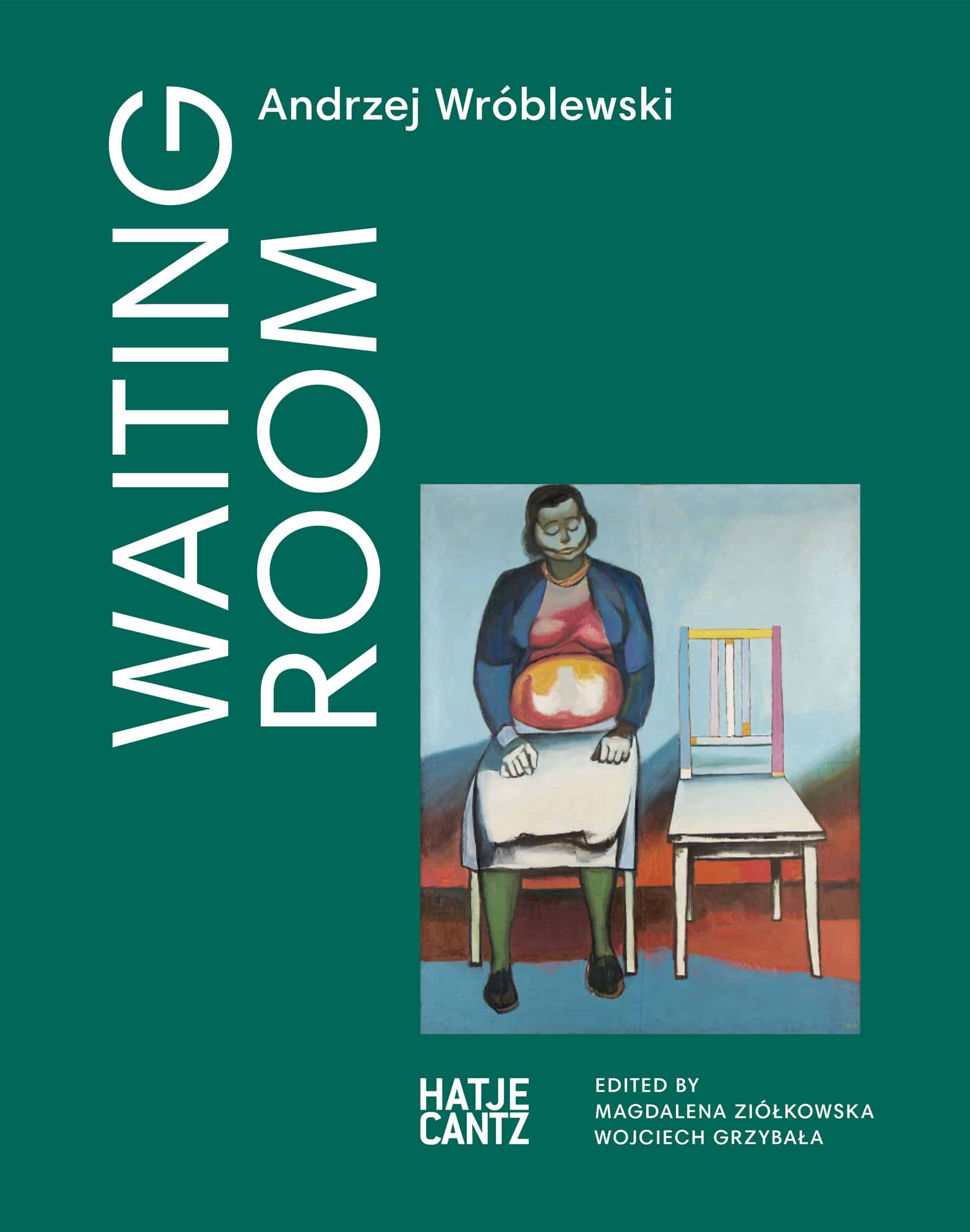

„Andrzej Wróblewski. Waiting Room” exhibition catalogue

Wróblewski himself talks about his role during the visit to Yugoslavia. As soon as he lands in Belgrade he says: “What can we say about ourselves? The fight against Socialist Realism started a long time ago. The resistance was particularly noticeable around 1950. External pressures, I mean especially the worst of them, which came from the Soviet Union, in fact, could never find followers in our artistic practice. Last year was a milestone in the life of Polish visual arts. The Exhibition in the Arsenal showed real paintings and gathered real painters ….”7 Does erasing one’s own Socialist-Realist past equal self-censorship? After all, it was Wróblewski’s Socialist Realist canvases from 1951–54 that brought him the largest number of scholarships, awards, commissions, and purchases on behalf of the Ministry. At the Meeting, Youth Rally in West Berlin, Search – Arrest, Union of Polish Youth Takes Command of the Air Force, biting political caricatures attacking bureaucrats, the capitalist world’s war plans or Home Army soldiers—these are just some examples of the stigma on Wróblewski’s artistic biography, the fact that he “was up to his ears in it,” as Anna Markowska writes.8 Or perhaps Wróblewski, as an envoy of the Polish thaw, should not be reminded of his own bankrupt experience of Socialist Realism, the submitted and rejected application to join the Party, especially when the trip takes place after Gomułka officially took power? Does Wróblewski consider himself to be one of those “real painters”?9 According to his letter to Wajda, yes. Some years later Janusz Bogucki will write: “as always, persistently, Wróblewski creates paintings, in which shapes and colors are devoid of an autonomous existence in the prescribed world of art. They are above all signs that determine the fate of man, and especially his social and moral condition.10 ” Wróblewski clings to this socio-moral relationship of art from start to finish.

The exhibition „Andrzej Wróblewski. Waiting Room” is accompanied by a catalogue with the same title, published in English, with seven critical essays by Ivana Bago, Branislav Dimitrijević, Wojciech Grzybała, Marko Jenko, Ljiljana Kolešnik, Ewa Majewska, and Magdalena Ziółkowska. The publication also includes the presentation of archival materials, photographs from Wróblewski and Majewska’s trip, and reproductions of 220 works by the artist. The catalogue is co-published and distributed by the prestigious German publisher Hatje Cantz in cooperation with the Adam Mickiewicz Institute.

„Andrzej Wróblewski. Waiting Room” at the Moderna galerija, Ljubljana, 15 October 2020 – 10 January 2021, curated by: Wojciech Grzybała, Marko Jenko, Magdalena Ziółkowska.

1. All quotes from Barbara Majewska’s review, “Salon ‘Po Prostu’ we wrześniu,” Przegląd Kulturalny, no. 50 (1956) p. 8.

2. Andrzej Wróblewski, “Jak odczuć ludzkość sztuki abstrakcyjnej?” Dziennik Literacki, no. 22 (1948), p. 4.

3. Andrzej Wróblewski, undated letter to Andrzej Wajda in Wróblewski według Wajdy, ed. Anna Król (Kraków: Muzeum Sztuki i Techniki Japońskiej Manggha, 2015), p. 33.

4. Ibid.

5. “Cultural report for the third quarter of 1956” in Cultural Reports of the Embassy of the People’s Republic of Poland in Belgrade in 1955, Ministry of Foreign Affairs archive, group 21, folder 749, bundle 53, p. 6. Two exhibition catalogues were attached to the report: 60 tableaux de la peinture modernę Yougoslave (Belgrade, 1953) and Salon 56: suvremeno, slikarstvo, i kiparstvo (Galerija likovnih umjetnosti, Rijeka, 1956)

6. Albert, Najnowsza historia Polski, p. 342.

7. A moment with … Andrzej Wróblewski and Barbara Majewska, NIN, no. 305 (1956) p. 6.

8. Anna Markowska, Definiowanie sztuki – objaśnianie świata. O pojmowaniu sztuki w PRL-u, (Katowice: Wydawnictwo Uniwersytetu Śląskiego, 2003), p. 103

9. The artist takes with him copies of his own works on paper (including the gouache (Birds) whose reproduction accompanies the conversation with the Polish guests in the Serbian journal), and perhaps a selection of other works.

10. Janusz Bogucki, Sztuka Polski Ludowej, (Warsaw: Wydawnictwa Artystyczne i Filmowe, 1983), p. 132.