Kama Sokolnicka, born in Wrocław, is the artist whose collages, installations and paintings border on language and metaphysics. Her latest exhibition entitled Sleep Disorders has just been opened for the first time in Paris. In an interview with Anna Tomczak, she talks about dreams, memory and her fascination with human behavior.

Anna Tomczak: At the end of January, the Progress Gallery in Paris has launched the exhibition featuring some of your pieces from the series under the working title Jet Lag. What other works are included in the show?

Kama Sokolnicka: I made a selection of my early works for the gallery with the view of highlighting the range of my interests. I also added two of more recent pieces in order to bring to the fore the pattern in the themes, forms, moods and materials. I’m not an advocate of linearity. I believe in the structures based upon many parallel or equivalent elements. The exhibition Sleep Disorders includes my works and thoughts pertaining to the subject which is developed further in my new project. I don’t view this exhibition in terms of some kind of retrospective.

AT: You created this new project during your residency in the OMI in New York and La Malterie in Lille. Jet Lag is in fact an oxymoron since jet means fast, and lag means slow. It is also a commonplace term that stands for the physical effects of a sudden time zone change. This condition represents our civilization very well. It seems we would love to erase the lag part from the human nature because it causes, for example, sleep distortions. Are they the main subject of the series?

KS: Last year, I concentrated on the usage of medical jargon about sleep to describe and/or look closer at the modern world. I dared to use the words lag and crisis quite freely and interchangeably. They both denote the potential for change and the promise they will pass someday. They both happen as a result of and before something else; they are in the present moment, time. To a large degree, time entails the compression or disappearance of some space. In a way, people lose touch with their surroundings if they change their whereabouts rapidly. You gain a wealth of experience, but you don’t feel it. It slightly resembles growing old. Many people enhance the impression of being in a permanent crisis to evolve: the crisis forces them to seek different solutions. Allegedly, capitalism demands to maintain the state of a constant crisis. I often wonder about the inconsistency, the gap and/or hollow between what we expect to see or we want others to see, and what we do actually see, what something was, is and will be. I am keen on the language of various sciences because the meanings are disjointed from the concepts. Let’s take for instance Restless Legs Syndrome. It is very difficult for me not to associate it with something more than it is supposed to stand for, although I know exactly what it means. Sleep distortions hold the idea of the psychological and cognitive dissonance.

AT: The links with Freud’s theory and your interest in psychoanalysis immediately spring to mind….

KS: I am much more interested in the mechanisms operating in humans and society, rather than the psychoanalysis itself. It is more about the reality as such, and not only psychoanalysis. I enjoy watching dogs that find a small hole and start digging deeper. Sometimes they find something, sometimes they run off suddenly to do something else.

AT: The exhibit in the Progress Gallery displays collages, paintings and sculptures. Jet Lag, in particular, explores “the sculpturability” of the material you work with. Was it the first time when you took this sort of approach to the project?

KS: Jet Lag is the part of a new series which was made during the aforementioned residencies. Material has always been important to me and I have always used specific material for a reason, even though I don’t focus on it in the process. Every project introduces me to some new materials, some of which stick with me for longer. A while ago, I added metal to cardboard and wood. I’ve been working with textiles other than canvas. Thus, Jet Lag is both new and not new to me. It is a piece of synthetic leather from China hung distinctively over the brass bar (the so called “fake gold”): a simple and at the same time complex mixture.

I always care about the ambivalence and balance. They need to coexist peacefully in one piece.

Material often speaks for itself. Therefore, it is a starting point, literally and figuratively speaking. I believe in the constructive use of debris or side effects of life or civilization

(e.g. disappointment and mental distress). They fuel my work.

When I start working on a new project, I like to sketch the main premise. For instance, I restrict gradually the tools and materials to those that seem absolutely essential to a given subject or a group of concepts. It is like some traces of feelings and premonitions were condensed to form a matter. Afterwards, the premise is intuitively modified. I add something here, I remove something there. There is no rigid agenda to follow.

AT: The statement about your work, which gives us some idea about the Paris exhibition, reads as follows: “In her works, she concentrates mainly on the picture perceived as memory, phenomenon known as horror vacui, the construct of a modern subject in relation to biography, space and the variety of stories distorted by emotions. She is deals with the concepts of ambivalence and disappointment, often connected with the peculiarity of a given place or territory.” Paradoxically, I’ve noticed amor vacui in your artwork. You do not shy away from reducing your works to single gestures and signs, leaving emptiness.

KS: The signs of horror vacui in people are both fascinating and frightening. Personally, I relate much stronger to amor vacui although horror also wields an unquestionable and unexpected power. Against all logic, the fear of emptiness can spawn the urge to make my own art in spite of my awareness of the fact that nowadays the art is famously overproduced. Anyway, I feel the need to react to the intensity of the world. I choose to deconstruct a picture, instead of fully constructing it, which is still a lot of fun. It may stem from my questioning of only seemingly solid pictures conjured up by people that range from political visions, through memory and PR strategies, to individual stories.

AT: Does horror vacui equal a constant need to lead chaotic day-to-day lives and to surround oneself with objects and other people (even outwardly)?

KS: There is also the need to gather things regardless of trends, one’s social status and wealth. My attention is caught, for example, by the surroundings of houses and balconies, by the piles of objects and sheds of various kind situated on allotments (also abroad). Yet another need of humanity is to be etched in someone’s memory (family member’s or wider audience’s ) after their death, which has upsetting and moving ties with people wanting to mark somehow their presence on earth.

AT: Some of your pieces were influenced in a way by your childhood and personal life. You glue together “found pictures” and hence recreate the fragmented nature of memory.

Is this the reason why you opted for collage as one of your means of expression?

KS: In principle, the starting point is – a recognized – experience. Everything I see, hear, read etc. gets filtered through this experience. In my opinion, any sort of montage seems adequate to represent the structure of memory at all levels (and I mean here memory in general). Montage has become the scaffolding of my projects, which use the past, not only deal with it. For instance, as a daughter of a gardener I can make use of experience and materials found in my home archive. However, the potential narration composed on the basis of my works touching upon a garden (or a montage of these works) doesn’t refer directly to me, nor a garden itself.

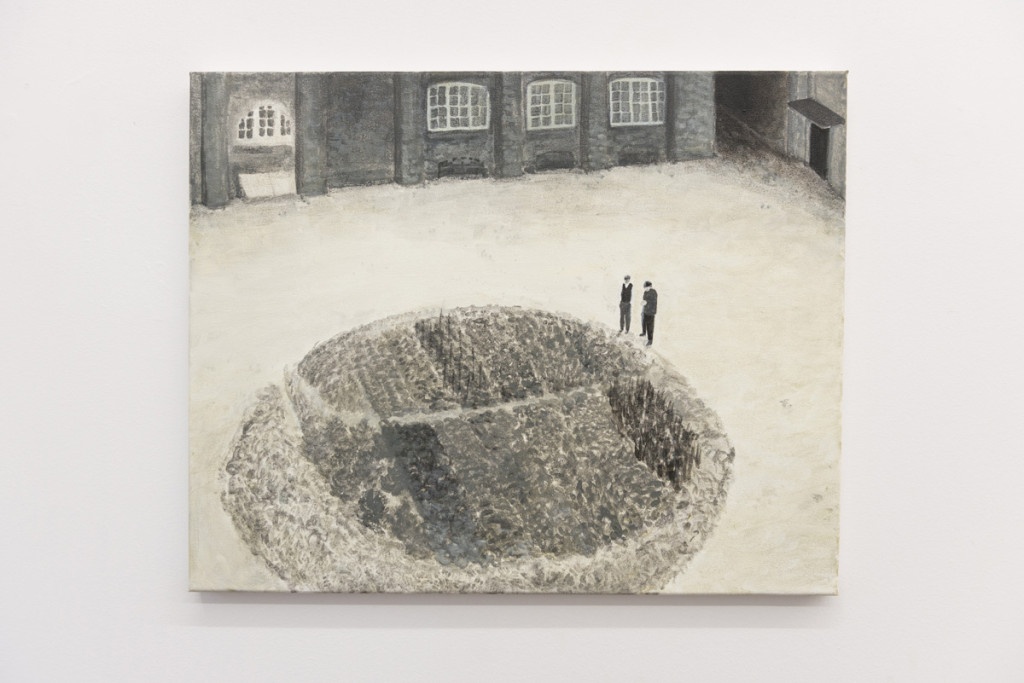

Kama Sokolnicka, Victory Garden, acrylic on canvas, 2012, photo Lores, courtesy the artist and BWA Warszawa

AT: According to Jan Assmann, cultural memory overpowers the individual memory. He claims that it is stronger than tradition and shapes the identities of next generations. Its task is to create the identity of a community in the future. Do you bear upon the idea of the individual vs. cultural memory?

KS: Of course, I do. That’s why I try not to think about the future. That’s why the series such as We Came From Beyond or Untitled were made. (“I am tired of the fight between skepticism and trust,” Mrożek once said).

Recently, I asked my friend from Montreal (another Canadian who emigrates to Europe) why she decided to leave her beautiful and wide country ideal for people worn out by the skeletons endlessly falling out of their closets. She said she was fascinated with the world in which every brick, gun, book, custom and behavior has its long cause-and-effect history.

When it comes to the individual memory, one of Sharon Hayes’ placards has just popped into my head: “My memory translates everything into something else.”

AT: Do you think collage and memory are alike? They are both created by means of “montage” of the pictures deeply rooted in the culture.

KS: Like I said, the resemblance clearly exists. What is interesting is not what we remember, but how we do it. Collage, as montage’s component and classic representation, came naturally to me. I like this technique. I completely dive in. Nevertheless, I display my collages as the part of a larger whole, a broader context of a project and among formally distinct works. At the times of the boom in collages, which everyone is now fed up with, even professionals hit the wall when they saw them on the exhibit; and this wall prevented them from seeing the complexity of an entire project, other works and techniques. I find it quite funny.

AT: You own past issues of magazines collected by your family. They provide material for your collages. How do you work with these visuals? Is archiving an important part of your artistic process?

KS: I add specific elements to my archive, such as things and materials that I notice while working on a given subject. I don’t pay a lot of attention to archiving. It just happens on its own. My collages are composed of the materials taken from magazines that were sent from West Germany to my grandmother and my father from the end of 1950s until the second half of 1980s. Surely, many people have similar collections in their homes. These magazines formed a mythical image of the West, which is typical for our kind of capitalism, in the minds of a few generations living in the Eastern Bloc. Even 30 year-old German magazines about interior design abound in political incorrectness, sexism, racism etc. These are obviously presented in the form of immaculate advertising photography, high-quality print and graphic design. Therefore, an appeal overrules the content (all about PR and illusion). Anyway, I own these magazines; and people haven’t changed so much since back then. Although the magazines are supposedly visually limited, I am still able to use them for various projects immersed in the presence.

AT: You use your own visual and esthetic “data base,” in the sense of memories or the Polish visual reality. Are your works determined by your origins? Or do you think that the East-West relation is no longer valid in the artistic landscape?

KS: I come from the society, in which failures and unsuccessful experiments prevail over other transformations. In my opinion, the artistic landscape is spacious enough to accommodate varied relations. If at one particular time the art word revolves around the universal language of art, it doesn’t mean that later on it can’t concentrate on the local shades and influences, or the other way around. It’s just that I feel bored with people blatantly treating identity as a product. Moreover, it seems to me that if the East-West relation is, sometimes painfully, palpable in the real life, then it would also have to be evident in art. There are different ways of coping with one’s origins. I really look forward to Agata Pyzik’s book Poor but Sexy. She probably makes some great points over there.

AT: You also make site-specific installations preceded by research and study. They remind us of a place’s history. Can we view territorialism mentioned above as rediscovery of some unique “territory,” as the appropriation of it for your own semantic field?

KS: Site-specific installations tend to resemble visible tips of the icebergs (they split, break off and float) whose bottom part is like the times which are already gone and permeated with past events attached to a place. If the project is designed for a concrete place, this place also carries my work, e.g. in case of the ted’ (now) project in Zlin, and a couple more works strongly embedded in local contexts. Initially, I appropriated this semantic field, in a way. But I returned it as soon as possible highlighting some part of it which was worth considering. I signal something; interpretation of a signal is a prerequisite for its power and redirecting one’s attention towards reception and a quality of a receiver.

The motif of territorialism runs through my different works, e.g. Quest or Different View, where I tackle the issues of human impulse’s consequences, understood as cognition and the expansion of knowledge (e.g. in the world or in the process of intellectual and media colonization).

Kama Sokolnicka, ted’, illuminated letters * on the roof of Bat’uv Institut, 2013, , courtesy the artist and BWA Warszawa *logo was built on the model of the first logo of Bata

Kama Sokolnicka, ted’, illuminated letters * on the roof of Bat’uv Institut, 2013, , courtesy the artist and BWA Warszawa *logo was built on the model of the first logo of Bata

AT: The exhibition of your work has just been opened in Poznań. It was previewed by your piece under the title Confusional Arousals, a collage on the box of unused photo paper. When the paper makes contact with the light and reagents, it reveals the invisible. Similarly, you make meanings rise to the surface. What is this surface exactly? Is it our culture, our Freudian Ego? Do you perceive yourself as a trickster who links the two worlds? Or is the romantic notion of an artist closer to you?

KS: No, I don’t believe in one all-encompassing role of an artist. I don’t have the faintest idea about an artist’s duties, nor do I play the role imposed on me. Nothing is definite nowadays. It is hard to keep one’s head above surface water without being surface oneself. I don’t like thinking about it this way. You can call it whatever you want. For as long as I can remember, I’ve enjoyed toying with showcasing and spreading the doubt and uncertainty. I explore the possibility of drawing strength from them. Psychological and esthetic helplessness filled the 90’s, the time of transformation I grew up in.

So what about this surface? The surface stands for the multitude of things: you can throw in some more concepts and the dots (artwork) could still somehow be joined. I discussed the idea of a surface in photography and optics with Dorota Walentynowicz, a curator of the exhibit in Poznań. The surface here is something that has no other side at all

or, in other words, has yet another surface on its other side. The surface covers nothing. It only reflects or transmits things. You can place something behind it, but not beneath it. By the way, I am not sure whether you can actually “look beneath the surface,” as the words suggest.

AT: Still a surface seems to draw the line between two different states….

KS: Or it may encompass both before and after, the inside and the outside. It may refute dualism; and be like the present, like here and now. A surface differs from, for instance, a transparent screen that makes things behind it partially visible. Despite what has already been said about a surface, mirror and screen, about the lines, about the visibility and invisibility (and I can only suspect what it is due to my own laziness, inability, unavailability and so on), I do find the pondering on the topic fascinating. Yet, I am not a philosopher. I prefer showing you my work connected with this subject to engaging in the “what if” blabber.

Kama Sokolnicka, Elfriede Jelinek with curtain (Vienna Set), c-print, foil, 2010, courtesy the artist and BWA Warszawa

AT: Why don’t we talk about your paintings now? They often depict architecture, the traces of people’s activity, such as houses, factories and interiors. But there is no sign of people.

KS: My paintings do portray gardeners, corpses even. Sometimes I only hint at the presence itself. However, if I have obstruction or clarity in mind, I want to paint radio station’s studio or a ship (with or without people on board) or an ice sheet, which reflects the light amid being colonized. The way I see it, paintings are also the elements of a montage. These elements are unique and distinct from the features of objects, drawings and collages. My work is invariably driven by looking and actually seeing; by the ambivalent foundations of Western capitalism, its products and consequences.

AT: So it is all about silence and amor vacui after all…

KS: But silence and emptiness have this tension based on the mind scrambling to fill in the gaps in the pieces you have at your disposal. There is lots of space between the gaps and discrepancies.

AT: Thank you.