Dobromila Blaszczyk: You live in the Republic of Macedonia, in Skopje. What brought you to this city?

Kinga Nettmann – Multanowska: Life! My husband Jacek’s job to be exact. He is a diplomat, the Ambassador of the Republic of Poland to the Republic of Macedonia. So the whole family moved here as a result.

D.B.: Several months ago in a telephone conversation you told us about an extraordinary find and an equally exciting, although somewhat tragic story connected to it. You had found works by Polish artists stored in the warehouses of the Museum of Contemporary Art in Skopje. How did this discovery come about?

K.N-M.: It is hardly a discovery, more like a “revisiting”. The whole story is not actually that exciting. As usual there was an element of pure coincidence. My husband and I came to work in Skopje at the end of April 2014, and at the beginning of the year there was an official reopening of the Museum of Contemporary Art. The museum had been closed to visitors for a few years due to the ongoing renovation and reconstruction of the permanent exhibition. We were lucky. The Embassy had received a new catalogue, published on the occasion of the museum’s 50th anniversary. It states that the museum holds a large collection of works by Polish artists. Over 135 names! I met with the director of the Museum Eliza Shulevska and the curator Zaharinka Aleksoska-Baceva. They showed me the museum’s warehouses, where I could truly see the value of the collection – many wonderful names of Polish graphic artists, painters and sculptors. Over 200 Polish works in one location, outside the Polish boarders. Unbelievable!

D.B.: How did the works end up in the Republic of Macedonia?

K.N-M.: They are a part of Polish donations for Skopje [then a part of Yugoslavia] after the tragic earthquake that took place in July 1963. The earthquake destroyed the whole city and turned it into rubble in a matter of seconds. The world united in helping Skopje, as if to counter the politics prevalent at the time – the culmination of the Cold War and the Iron Curtain. Broken Skopje received generous help. Poles were one of the first donors. We provided not only material help, but also our “know-how”. During the reconstruction process, the Manager of the UN Skopje Urban Plan Project title was given to Adolf Ciborowski, the main architect and urban planner working on the post-war reconstruction of Warsaw. Stanisław Jankowski “Agaton”, another great figure in the history of Warsaw, managed the engineers of the official Polish construction agency Polservice. Polish workers also cleared the city of debris.

D.B.: Is there more information about the story of the collection?

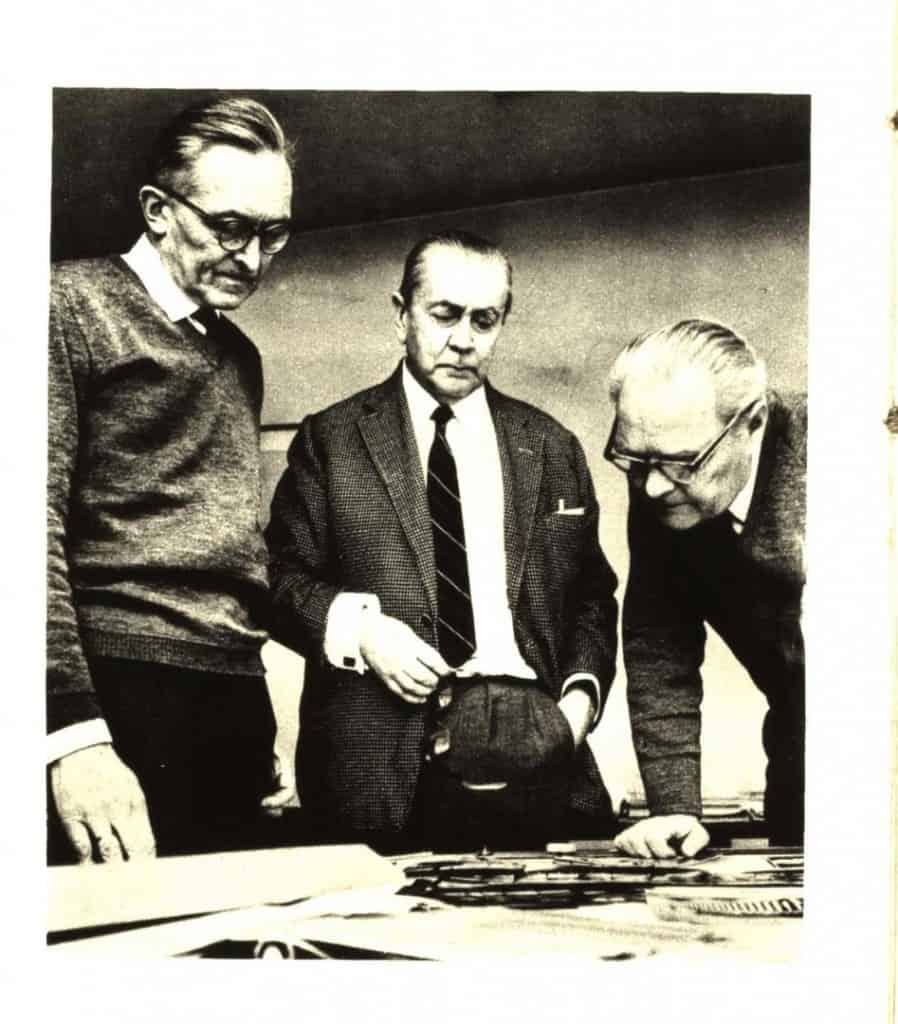

K.N-M.: Yes, I am trying to find documentation in order to trace the sources and how it all happened. I managed to uncover some facts. For example, I know that Polish pieces arrived in several instalments. The first big collection was initiated in October 1963 at the 4th International Congress of the International Association of Plastic Arts in New York, where the authorities of Skopje officially appealed for solidarity and asked for artist donations from all over the world. Countless [over 1000] works were sent to Skopje, including Polish pieces. Further Polish donations arrived in Skopje in 1965, after the visit of the official Polish delegation to Yugoslavia [November 1965], headed by Prime Minister Józef Cyrankiewicz and the First Secretary of the Central Committee of the Polish United Workers’ Party, Władysław Gomułka. A third wave of donations followed about a year later after the design prize for the Museum of Contemporary Art was awarded to a group of Polish architects, the so-called “Tigers”—Wacław Kłyszewski, Jerzy Mokrzyński, Eugeniusz Wierzbicki [May 1966]. For example, two donated sculptures arrived in Skopje in July 1966, following twenty-four oil paintings and forty-five prints, which were sent over a month earlier. Further sculptures and medals – forty-four works in total – reached Skopje in December 1967. I can provide you with such detailed data because I have copies of duty exemption documents, which I found in the City of Skopje Archive. In later years there were donations from individual artists during their visits or exhibitions in Skopje or the Republic of Macedonia.

“Tigers” – Wacław Kłyszewski, Jerzy Mokrzyński, Eugeniusz Wierzbicki

Adolf Ciborowski photo Kiro Georgiewski

D.B.: The collection includes works both by renowned artists and those less known. What can one find in the Skopje Museum Collection?

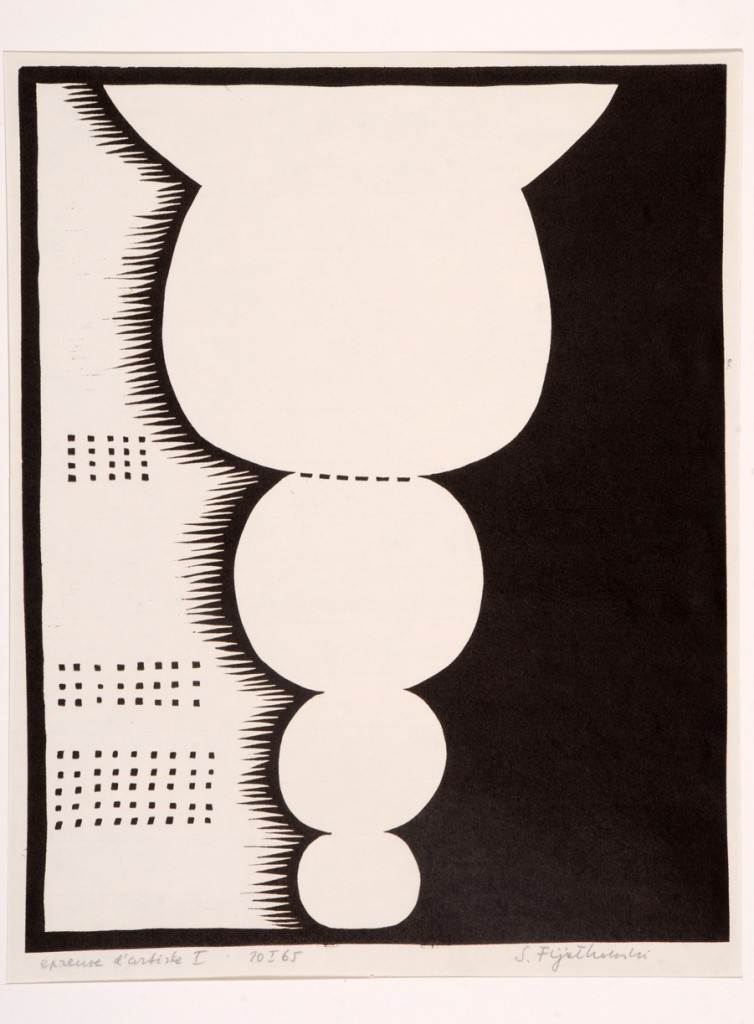

K.N-M.: This question should be posed to the experts who have managed to have a look at the Skopje pieces. Following our request, the Ministry of Culture and National Heritage of the Republic of Poland turned to Jarosław Suchan, the director of the Museum of Art in Łódź, who delegated two employees to Skopje, Magdalena Ziółkowska Ph.D., an art historian, and Bogumiła Terzyjska, a conservator. They are the ones who can evaluate and describe the value of this collection. Considering myself to be more of an art aficionado than a specialist, for me it is important that the collection includes the names of Polish artists that are universally recognised [Kiejstut Bereźnicki, Marian Bogusz, Jerzy Nowosielski, Tadeusz Dominik, Stanisław Fijałkowski, Zbigniew Makowski, Roman Starak, Andrzej Strumiłło, Henryk Stażewski, Karol Tchorek, or the recently deceased Jan Berdyszak, among others]. There are also forgotten names, and what is without a doubt extremely important is that the collection itself offers a condensed fragment of what was happening in Polish visual arts in the 1960s.

Jerzy Nowosielski,

Mountain Landscape, 1964, oil on canvas,

70 x 100 cm, courtesy The Jerzy Nowosielski’s Foundation and Embassy of Poland in Skopje

Henryk Stażewski, Kompozycja (The Composition), 1964, courtesy the Embassy of Poland in Skopje

Zbigniew Makowski, Composition, 1962, oil on wooden plate, 43,5×36,5 cm, courtesy the artist and Embassy of Poland in Skopje

D.B.: The architectonic design of the Museum itself, which to this day towers over the city on Kale Hill, is also an effect of Polish and Yugoslavian mutual efforts. Could you tell us a bit more about the story of the design and construction?

K.N-M.: Poland provided great help to Skopje, considering our limited means at the time. Among other things, the city was granted small wooden residential houses (nicknamed “baraka” by the locals), which were placed in the Taftalidze quarter, which back then was filled with many temporary dwellings donated by various countries. Poland also built the Maria Curie-Skłodowska Chemistry Vocational School, and after the visit of the Polish communist leaders in November 1965, it conducted and financed the “Public Competition for the Design of the Museum of Contemporary Art in Skopje”. Earlier in 1964 Poland offered to finance the design of the building, which would serve as an institution of culture, and would be yet another Polish gift to the city. Following the advice of Adolf Ciborowski, the Manager of the UN Skopje Urban Plan Project, and fellow Pole himself, it was decided during the city’s reconstruction process that the Museum of Contemporary Art would be the gift, as, at that time, a building was needed to provide exhibition and warehouse space to the great amount of art donations from all over the world. In January 1966 the Polish Architects’ Association announced the Public Competition for the Design of the Museum of Contemporary Art in Skopje”. There were 89 competing designs, with results announced in May. Design No.16 created by the “Tigers” (Wacław Kłyszewski, Jerzy Mokrzyński, Eugeniusz Wierzbicki) won. The justification read: “The work is awarded 1st prize due to good functional solutions, spatial values, the simplicity of the employed means, and implementation qualities” (“Architektura” 10/1966, 424). The construction of the museum was financed by Yugoslavia, mostly from the Fund for Aiding the Reconstruction of Skopje. The building opened to visitors on November 13th 1970. At that time the museum collection included over 2000 works of artists from over 40 countries. We don’t know the details, but we are aware that Oskar Hansen, a Polish visionary architect, also put forward his design. It was difficult to implement, because it featured movable platforms, so-called “umbrellas”, which would be used not only to exhibit artwork, but also to rouse its creation. A copy of the original design hangs in the Ambassador’s office at the embassy, which now belongs to my husband.

Stanisław Fijałkowski, 10.I.65, 1965, linocut,

62,5 x 48,6 cm, courtesy the artist and Embassy of Poland in Skopje

D.B.: It is a relatively new subject, which has been forgotten or unheard of by most people. How do you intend to commemorate this unusual gesture made by Polish artists?

K.N-M.: Now that we’ve learned from the experts just how precious the collection really is, we plan to prepare a catalogue, just a digital one for the time being. The collection is photographed and indexed. Moreover, in order to promote this “Polish treasure in the Balkans” to a broader audience, who include cultural institutions, we are printing a small desktop calendar for 2015. Naturally the grand finale would be an exhibition, but there is still a lot of work to be done before that happens. It would also be a wonderful gesture on behalf of the museum, if they incorporated a few of the Polish pieces into their permanent exhibition (so far only “Kompozycja” [“The Composition”] (1964) by Henryk Stażewski is on display). It is our dream that Polish tourists, who travel to Skopje more and more often, would first direct their steps to the Museum, to look at the original works of Polish Masters of painting, graphics, and sculpture, after parking their buses on the car-park by the Museum of Contemporary Art, instead of heading to the centre, as they usually are accustomed to doing. We would also love it if both the local and Polish tour guides were aware of the fact that the elegant and timeless building of the Museum of Contemporary Art, which towers picturesquely over the city, is of Polish design, and that it houses an important Polish collection. So far there is no awareness, neither here nor in Poland. And our painstaking task is to create this awareness.

D.B.: I understand that you’ve begun your own research and enquiries.

K.N-M.: Yes, I want to create an image of those times both for myself and for others. After all, the Polish collection still exists in broader context of the aid that came from Poland and the world. The Museum became a beneficiary of this grand gesture for Skopje. Other great artists also donated their works to the city – including Picasso – whose nam thrills everyone who visits the Museum. Therefore by looking at local archives and libraries, or through talking to people who have some knowledge of it all, I am trying to find some useful leads in order to establish the chronology of events that took place, and commemorate the Polish involvement in the re-building of Skopje appropriately. I found press articles from that period at the National Library in Warsaw. There are also important documents in the collection of the Fund for Aiding the Reconstruction of Skopje in the City Archive. I also found Adolf Ciborowski’s son Maciej, equally an architect, who spent several years in Skopje with his father when he was young. In his correspondence he recalls the images he remembered from that time. I also talked to Polish artists whose works may be found at the museum. They reminisced about their artistic youth – after all, they were around 30 years old at the time – and the word “Skopje” instantly sparked a myriad of emotions within them. All this creates the backdrop to the collection and is its integral part. Skopje is a city of solidarity – special and unique – and this atmosphere survives to this day. There is a Romanian hospital called “Bucharest”, there is the “finska baraka”, i.e. the Finnish, but not solely Finnish, wooden houses. There are French, Czech and Soviet residential blocks, the German nursery and school, there are streets named by countries and capital cities that provided aid. I would like us in Poland to have a greater awareness of the fact that we helped create modern Skopje. For us as tourists to feel a stronger bond with it, to share a solidarity with it and the inhabitants of the Republic of Macedonia, and also today, for the Polish collection to be studied by Polish and Macedonian researchers, to give it new life and a place within collective memory. This time, forever. I don’t think these dreams are unrealistic…

[Kinga Nettmann-Multanowska, the wife of the Polish Ambassador to Skopje, Jacek Multanowski]

Skopje, Sept. 21, 2014

Kinga Nettmann – Multanowska

PhD in English linguistics (specialised in comparative studies); former employee of the English Philology Institute at Adam Mickiewicz University in Poznań, a translator, teacher of Polish as a foreign language with experience in Kyrgyzstan and Georgia.

Significant publications:

(1) English Loanwords in Polish and German after 1945: Orthography and Morphology in the Bambareger Beitraege zur Englischen Sprachwissenschaft series, Wolfgang Viereck (ed), publisher: Peter LANG, Frankfurt am Main, Berlin, Bern, New York, Oxford, Wien, vol. 45, 2003 [author];

(2) Polscy artyści w Gruzji, Henryka Justyńska, Tbilisi, 2006 [Polish version editor, translation into English];

(3) Henryk Hryniewski, Tbilisi, 2007 [co-author, Polish version editor].

All activities relating to the Collection of Polish Art in Skopje supports the Ministry of Foreign Affairs of the Republic of Poland and the Polish Ministry of Culture and National Heritage

2015 Polish Embassy Calendar featuring the works from the Skopje Collection of Polish Art

Translated by Ewa Tomankiewicz

Tadeusz Dominik, Potęga nieba, 1964, oil on wood, 41 x 53,5 cm, courtesy the Embassy of Poland in Skopje cm

Jan Berdyszak,

Stal i powietrze (Steel and Air), steel, 115 x 76 x 60 cm, courtesy the Embassy of Poland in Skopje

Roman Starak,

Industrial Landscape,

1965, 60 x 86 cm, courtesy the artist and Embassy of Poland in Skopje

(Edition 7/35)

Museum of Contemporary Art in Skopje, photo courtesy the Embassy of Poland in Skopje

Museum of Contemporary Art in Skopje, photo courtesy the Embassy of Poland in Skopje