A summary of 2020 in the world of film art must be completely different from one made under normal circumstances. It is not easy to simply choose a few recommended films without mentioning the events that have been taking place all over the world this year. Of course, the coronavirus pandemic affected numerous industries, but it was particularly significant for the cinema. The fact that cinemas were closed for the greater part of the year completely changed the film premiere calendar and disturbed the traditional course of making and promoting new film productions. This provoked numerous discussions on the future of the industry, which has been standing at the crossroads for a long time now, with the pandemic only accelerating certain inevitable processes.

In fact, the year 2020 can be summarised by writing only about important films, ones whose premieres were rescheduled in anticipation of better times. I decided to describe the year by choosing productions which reached viewers in one form or another, and which, in addition to their outstanding quality, attempt to comment on various facets of the surrounding reality. Considering the specific nature of Contemporary Lynx, I will focus on English- and Polish-speaking films, with one exception at the end.

Small Axe, dir. Steve McQueen

The problems we faced in 2020 could not be reflected in a more intriguing way than in this film series created by the former artist(a winner of the Turner Prize), who has been pursuing a successful career as a feature film director for years. Small Axe is a series of films of various lengths, each of which tells a different story about the lives of black immigrants in London from the 1960s to 1980s, mostly based on factual events. Brilliant acting and awareness of form, both characteristics of Steve McQueen have resulted in extremely moving stories which fit in well with the Black Lives Matter movement, at the same time recollecting covert systemic racism in Britain historically and posing important questions about contemporary times. Although the anthology was created for television and streaming, some of the parts of the series were screened at film festivals, where critics compared it to Krzysztof Kieślowski’s Decalogue.

Mank, dir. David Fincher

LikeLike Mcqueen’s works, the most recent film by David Fincher was made for a streaming service (Netflix), which has become increasingly common and symptomatic in a year that cinemas were closed for so long. The director of Fight Club, reaching for a screenplay by his father, pays tribute to Herman J. Mankiewicz, screenwriter and author of the legendary Citizen Kane (1941). Mankiewicz is often considered a victim of Hollywood conflicts and the despotic personality of the film’s director, Orson Welles. Fincher has mastered a play on the cinema style of the 1940s, posing questions about film-authorship which is still important today. His film becomes a battleground between the written text and the power of intricately created images. Who is the author of a given film – the one who tells the story or the one who gives it its visual form?

Mank, dir. David Fincher

Mank, dir. David Fincher

I’m Thinking of Ending Things, dir. Charlie Kaufman

Another Netflix production on the list. Charlie Kaufman — a renowned playwright/writer who has been releasing original films every few years — once again invites us to enter his strange, intricate world. A story about a couple on the verge of breaking up becomes a pretext for free, surreal reflection on identity, memory and love. Kaufmann is most of all interested in the issue of the truthfulness of human relations. Can we really bond with other people if we are trapped in our own minds for the greater part of our lives?

Possessor, dir. Brandon Cronenberg

David Cronenberg’s son is taking over the best models of his father’s work and is continuing his style of body horror with a substantial extra in intellectual content. Possessor is close to such films as Videodrome (1983) and eXistenZ (1999), but it is not just their mere copy. Brandon Cronenberg has created a mature work, at the same time having a great feel for the style he is referring to. A story of wealthy people who, with the support of a certain organisation, can control ordinary people, forcing them to commit murders, touches on a crucial coincidence of money, power and technology, at the same time asking controversial questions about the existence of free will, which makes some of the film’s scenes virtually frightening.

Possessor, dir. Brandon Cronenberg

Possessor, dir. Brandon Cronenberg

Nomadland, dir. Chloé Zhao

Born in Beijing and working in the USA, this director won the top prize at the Venice Film Festival (one of only few which took place this year) with her unassuming, pared-down film. Nomadland is a story both about a woman seeking her independence and about recession and the less-attractive image of the United States. The film features professional actors and a real-life community of contemporary nomads who left their homes for financial reasons. An outstanding, strong but nuanced Frances McDormand has taken the central position in the film.

The Nest, dir. Sean Durkin

Sean Durkin does not release his films very often, but none of them leaves viewers indifferent. His main protagonists are usually lost women, dependent on men, who must go through a traumatic experience to realise their own situation and find inner power, beginning a process of emancipation. Although the director is Canadian, he has found his place in the UK. The Nest, set in the 1980s, is a painful dissection of Thatcherism and the neoliberal propaganda of the time. The director does not present a comprehensive social panorama, showing instead of the tragedy of an unhappy marriage in which the wife (Carrie Coon) must suffer the consequences of the irresponsible decisions of her husband (Jude Law), who is repeatedly beguiled with the promise of huge income and fast social advance.

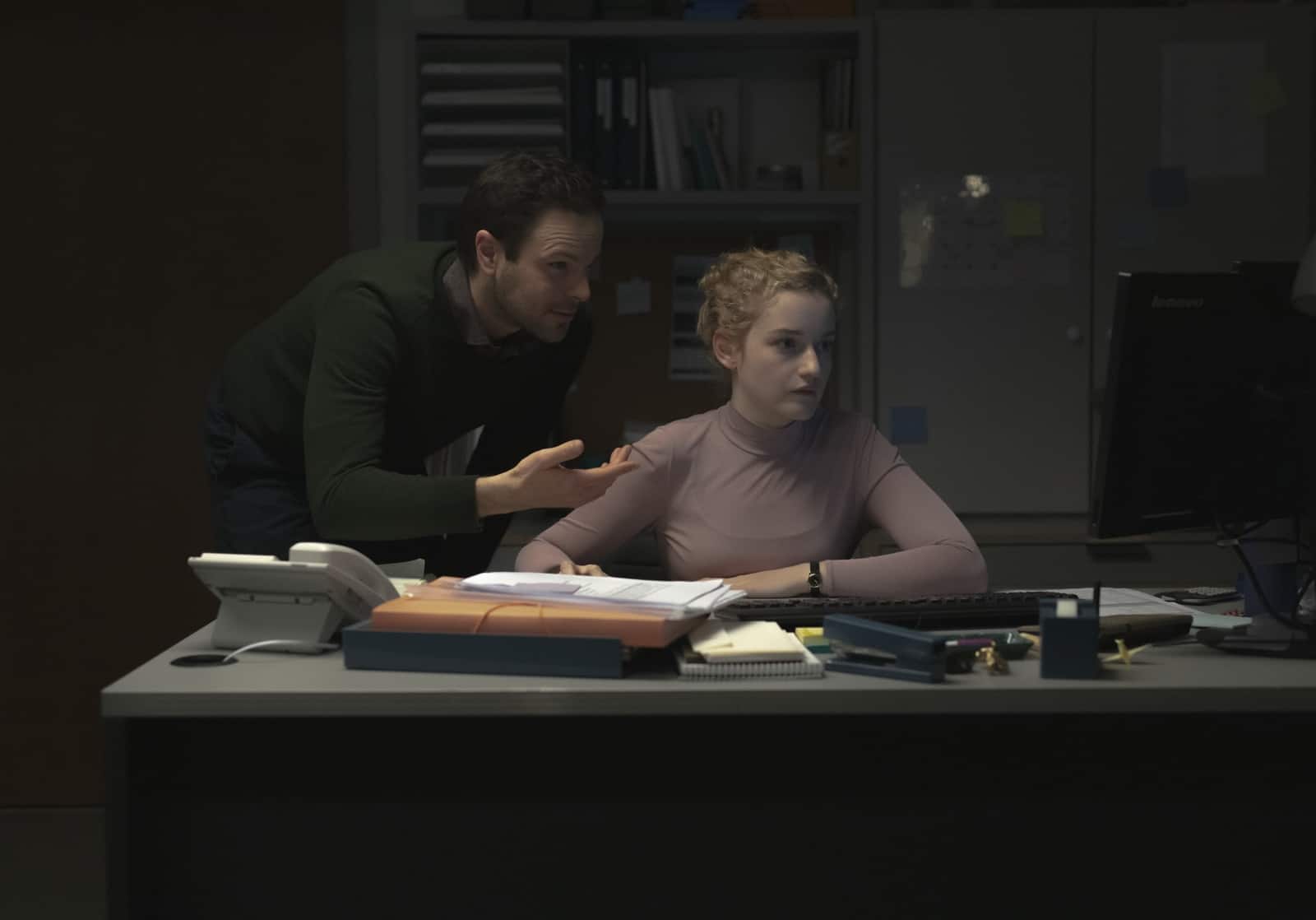

The Assistant, dir. Kitty Green

Kitty Green, Australian director and editor, is familiar with feminist topics, and one of her documentaries was devoted to the Ukrainian group FEMEN. Her American debut, which is at the same time austere and laconic and keeps you on the edge of your seat, is loosely connected with the discussion around #MeToo. Resembling early productions by Michael Haneke, the film is focused on showing the ordinary routine activities pursued by the main protagonist (Julia Garner) who is a young but conscientious assistant to a famous film producer. She not only handles typical office tasks, but also arranges his personal affairs, which leads to her discovering gradually various instances of a generally accepted malfeasance. Green depicts the nature of everyday corporate oppression in an excellent way; his film shows situations on the verge of mobbing and constant fear, experienced so often by women working for superiors infamous for sexual debauchery. Taking into account that the plot is set in a film production company, The Assistant can be seen as the grimmest production on film-making in history.

The Assistant, dir. Kitty Green

The Assistant, dir. Kitty Green

Sweat, dir. Magnus von Horn

The first Polish film on our list was classed as one of the most interesting productions of the year by the selection panel of the Cannes Film Festival. Von Horn comes from Sweden but has lived in Poland for nearly a decade cooperating with the Łódź Film School and creating outstanding, unobvious films, full of apt social observations and subtle emotions. In his second feature film, he depicts a few days in the life of a fitness trainer and Instagram celebrity. The contrast between the Internet and real life is growing bigger and bigger, aggravating painful loneliness. The face of lead actress Magdalena Koleśnik, (awarded at the Polish Film Festival in Gdynia) becomes the film’s leitmotif. The face is, at the same time a product, a trademark, and a mask hiding unspoken emotions.

Sweat, dir. Magnus von Horn

Sweat, dir. Magnus von Horn

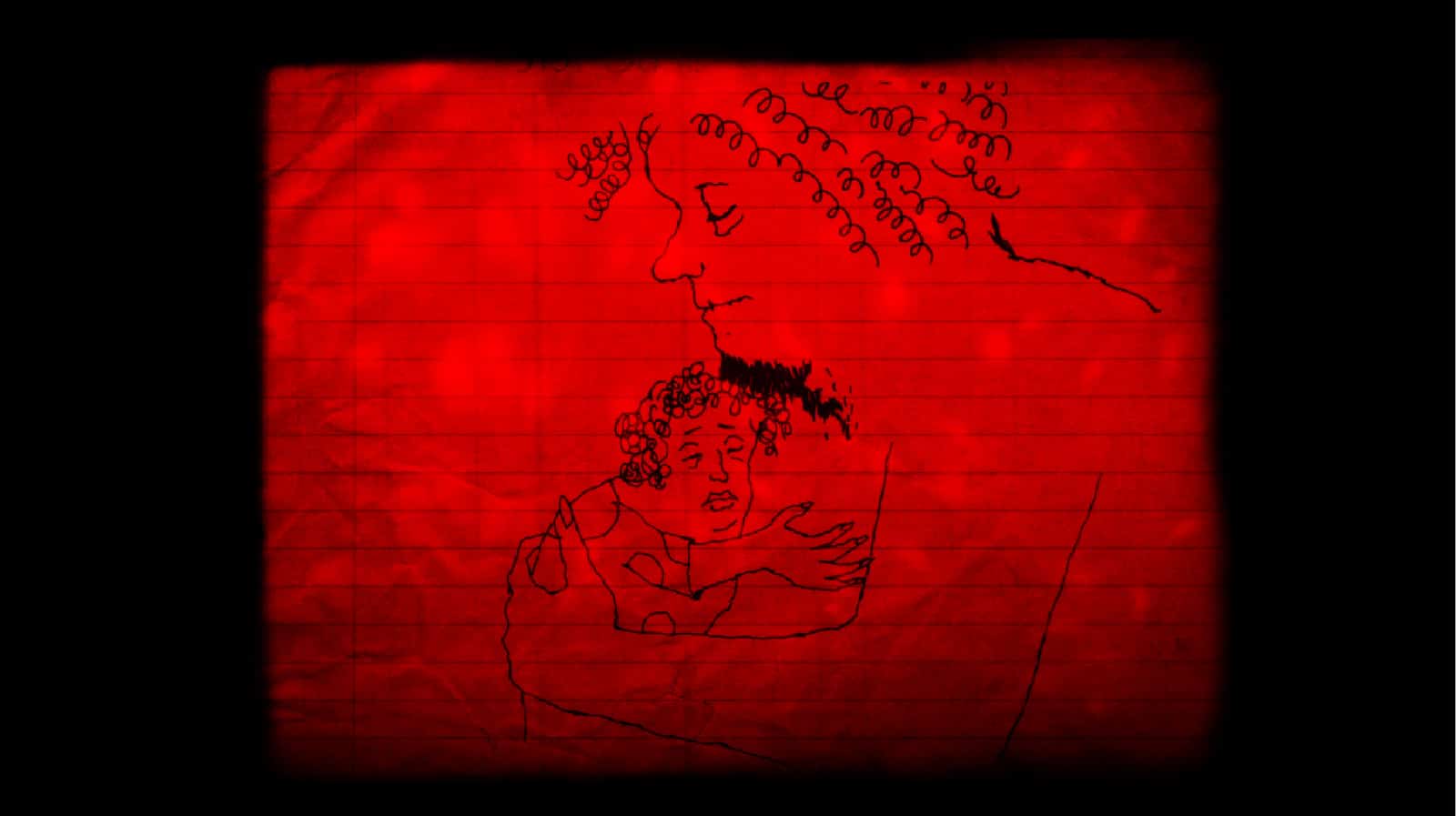

Kill It and Leave This Town (Zabij to i wyjedź z tego miasta), dir. Mariusz Wilczyński

The Polish phenomenon of the year. The film was screened during the Berlin International Film Festival and is the first animated film to win the Film Festival in Gdynia. Mariusz Wilczyński is a self-taught artist whose unique short animated films have been showcased at a retrospective exhibition at MoMA in New York. He prepared his feature-length debut for fourteen years: a dark, impressionistic, sad and nostalgic story about childhood in communist-era Łódź. Wilczyński, who appears in the film himself, demonstrates the world of people who are not loved, lonely, who can be shown compassion through art. The animation, full of references to Polish reality (you can hear the voices of outstanding figures from Polish culture, often those who have passed away, e.g. Andrzej Wajda) is at the same time a universal, poetic reflection on death and the things we can save against all odds. It is not easy in reception, but it is one of a kind.

Kill It and Leave This Town (Zabij to i wyjedź z tego miasta), dir. Mariusz Wilczyński

Kill It and Leave This Town (Zabij to i wyjedź z tego miasta), dir. Mariusz Wilczyński

Another Round (Druk), dir. Thomas Vinterberg

Last but not least, the winner of this year’s European Film Awards and a strong candidate for the Oscars. Vinterberg — once a pillar of the Danish Dogme movement, together with Lars Von Trier — every now and then returns with an excellent, revealing film which touches on difficult issues in a communicative and audience-friendly way. A story about a group of middle-aged teachers who, in order to break up everyday routine, decide to live and work being slightly drunk., it is an exceptionally warm film, even cheerful at times, but at the same time profound in an unobvious way. As in Von Trier’s The Idiots (1998), the director tells a story about the stagnation of highly-developed capitalist society: trapped in rituals and social conventions, needing to leave the beaten track, the characters achieve this by pursuing strange and unconventional activities. The protagonists’ ‘therapy’ is risky and lined with despair, and while it is not a way to happiness, it compels them to rethink their current lives and encourages them to build something different, based on new principles.

It is not a coincidence that this film gained so much acclaim in 2020. The pandemic has also made us break with our habits and redefine a lot of things. We know that the world ‘after’ will not be the same. Although we have many concerns, perhaps we will be able to make it a bit better than before, at least in some respects.

Another Round (Druk), dir. Thomas Vinterberg, photo by Henrik Ohsten

Another Round (Druk), dir. Thomas Vinterberg, photo by Henrik Ohsten