Abakans — Not simply fabric constructs, nor just sculptures, but three dimensional forms known as “soft sculptures”. Abstract and very organic, these are the — almost literal — fruit of the imagination and the artistic investigations of Magdalena Abakanowicz. Although she began her investigations in painting, she came to find her best means of expression in Abakans. The artist has said repeatedly, that the flatness of the huge canvasses she painted at the beginning of her career, haunted her. From very early on, Magdalena felt the need for a third dimension. This need for multidimensionality has been present in all her later works, and it has directed and marked the way she has developed as an artist.

Magdalena Abakanowicz, 1960s, photo artist’s archive

The 1960s in Poland was a real heyday for artistic tapestry. It could be largely ascribed to the long weaving tradition of the central part of Poland, as well as the advancement of schooling in artistic tapestry technique, in particular at higher education centres in Warsaw, Poznań and Łódź. This coincided with a global rise in interests in tapestry. An expression of this heightened interest was the Biennale Internationale de la Tapisserie, organised every two years since 1962, in Lausanne. The organisers wanted to gather artists from all over the world, and show the public modern 20th century tapestry. This important event which continued until 1995, undoubtedly contributed to the popularisation of Polish artistic tapestry, and exposed it to a wider audience. Weaving became a widely recognised representative of Polish culture in the world. Galleries and museums from all over the world became intrigued by the growing group of active Polish artists representing “Polish textile art”. Jolanta Owidzka, Wojciech Sadley and Magdalena Abakanowicz caused a particular stir. They surprised the doyens of the very traditional ‘French School’ of tapestry, in particular the painter and celebrated tapestry designer Jean Lurçat, who was one of the initiators of the biennale. The Polish artists were distinguished by their work ethic. The majority of them not only designed the tapestries, but made them themselves, as opposed to the convention of the time, according to which the artist was first and foremost a designer, who only cooperated with the weaver in the creation of the tapestry. The Poles, unlike the French, often designed the tapestries directly on the loom. They also tried out various yarns which they dyed themselves. They used various weaving techniques while displaying a very modern approach to composition. In effect, they created relief-like structures in the fabrics, which by far exceeded what was considered a classic tapestry.

Magdalena Abakanowicz, 1960s, photo artist’s archive

Such were the first works of Magdalena Abakanowicz, who in the opening years of the 1960s gradually “peeled” her works away from the wall, and infused them with an increasingly individual style. These first trials with the fabric resulted in tapestries which featured an array of unique elements, uncommon for that medium. The final transgression and breakaway from the cannon of the tapestry swiftly followed. In 1962, Magdalena took part in the Lausanne Biennale Internationale de la Tapisserie. Her “Kompozycja białych form” [Composition of White Forms] which she presented there captured everyone’s interest, while simultaneously spreading controversy. Although this was still a flat, wall-mounted piece, it already featured relief elements, an interesting modern composition of geometric forms, as well as a tasteful colour scheme of beige, white, grey and sepia. It stood in direct contrast to the then universal trends in the art of weaving. Primarily however, it heralded Magdalena’s later interest in multidimensionality, and demonstrated her attempts at using various types of weaving materials, yarns and making use of all their characteristics. The fabrics designed and produced by the artist bore witness to her incredible consistency in her work. She wrote: I’ve never been interested in the fabric with its role as a wall decoration. I’ve been interested in what could be done with the fabric, how to shape the surface into a relief, how to do the movable patches of bristle, and how can this structured surface bulge out, burst and reveal mysterious depths through the cracks [1].

Magdalena Abakanowicz, 1969, photo artist’s archive

Magdalena Abakanowicz, Queen, Orange with Black, 1970/1980, 335 x 282 cm (fragment), photo M. Gardulski, Starmach Gallery

In mid-1960, the creative investigations of Magdalena Abakanowicz finally crystallised and became a clear vision. The multidimensional tapestries of the artist were presented on the International Biennale in São Paulo in 1965. They were a real revelation, a sensation, but also provoked a certain amount of dismay caused by their surprising visual effect. The prize which Magdalena Abakanowicz won at this biennale opened the way to international exhibitions, and made her a world-famous artist. She said of her success: Abakans brought me global fame, but they were also a burden, like a sin you cannot admit to. Because weaving closes the doors to the world of art [2].

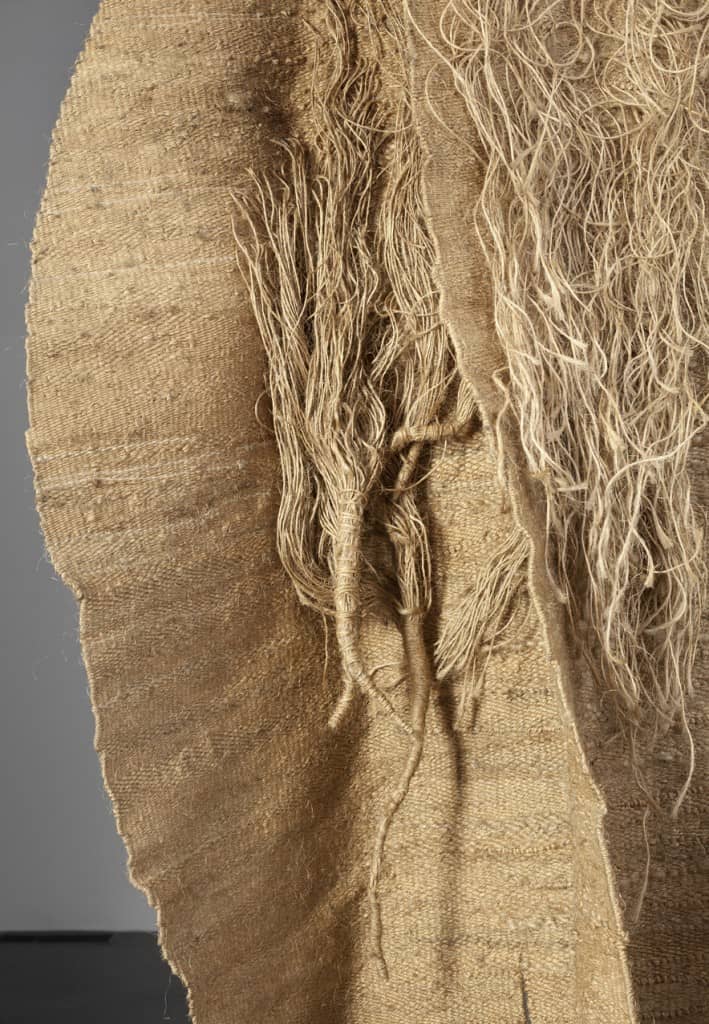

Abakans, which were the result of an intensive creative process, are three dimensional sculptures of complicated and convoluted shapes, with intriguing surfaces and texture. Often, one could enter them, penetrate their insides, step into them like into an empty tree trunk, which can give us shelter. Abakanowicz passed beyond all possible schemata of thinking about fabric, and expressed herself as a sculptor. Undoubtedly, this decision required uncommon courage. She detached the fabric from the wall and bestowed it with three dimensional form, marked with an original finish. Thick coils, loose tassels, visible weaves, thick textures used alternately with gaps and slits, which suggested associations with the human body, or more generally a body, live tissue. Abakans stood in opposition to traditional weaving. They raised weaving to the level of a full-fledged art genre, not only a craft as it was perceived thus far. Abakans irritated people. They were ahead of their time. In weaving: French tapestry, in visual arts: pop-art and conceptual art, and here we have something magical, complicated, huge… A foreign language (…) I didn’t want to explain Abakans. They were to speak for themselves. I couldn’t verbalise their mysteries [3].

Magdalena Abakanowicz, Queen, Orange with Black, 1970/1980, 335 x 282 cm, photo M. Gardulski, Starmach Gallery

Magdalena Abakanowicz, Lady, 1970/1980, 300 x 280 cm, photo M. Gardulski, Starmach Gallery

Abakans took on basically four forms: oval like “Abakan Lady” (1970/1980), rectangular like “Abakan Queen” (1970/1980), those that resembled clothes, like — “Czarne ubranie z jutą” (1975) [Black Clothing with Jute], and finally, works which looked like hollowed out tree trunks — “Tuba” (1976) [Tube].

The force of Abakans resides in their convolutions. They have always offered a lot for the imagination to play with. Many of them bring to mind fantastically shaped plants. Others are reminiscent of venous human internal organs. A lot of them are very strongly erotic, clearly alluding to female genitalia in their form (or shape). Their expressiveness and erotism, combined with the softness of the yarn result in a suggestive and disquieting effect.

Abakans broke free from the strict categorisation of conventional art. They did not lend to easy pigeonholing. Although they undoubtedly are sculptures created from woven fragments, they are simultaneously — and surprisingly — soft, which is not a quality usually ascribed to classic sculpture.

An important consequence of the “softness” of the Abakans is their ability to move. They can be stirred to movement by wind, the presence of an onlooker or a touch. Such movement is biological and incredibly close to nature. It is a movement which has been present in nature since the beginning. It is the way tree-branches, sand particles and leaves move. Only a woven, soft object can move in this manner. No other sculptor’s material has so much life in it.

In 1968 Magdalena Abakanowicz executed an open air installation in Łeba by the Polish seaside. Abakans were placed on the beach in an open space, and moved by the wind, they seemed to be living, biological life-forms [4]. The artist highlighted that the movement of the Abakans is like the the monotonous, sleepy rhythm of the ocean’s waves. She thought that only waves are capable of such impact. When she noticed that Abakans also have this characteristic, she delighted in that discovery for a long time [5]. This observation inspired her to develop her own concept of presentation of the Abakans. The artist organised a series of exhibitions in which she focused primarily on highlighting these biological movements. Visitors would move freely among the enormous sisal works hanging from the ceiling, which would make up the walls of the space the visitors had entered. She was interested is displaying whole sets which arranged, organised space, and created a specific ambiance, a slightly theatrical, scenographic effect. “Czarne środowisko” [Black Habitat] (1970-1978) is a set of 15 huge 3 metre high Abakans, which created their own “natural habitat”. Such similar sets of works — whose impact resides in the amalgamation of many almost identical elements — will also appear later, when Abakanowicz started creating “crowds”, composed of a series of repetitive figurative sculptures made of old jute bags, or cast in bronze.

Magdalena Abakanowicz, Tube, 1976, 300 x 90 cm, photo M. Gardulski, Starmach Gallery

In her notes, Magdalena Abakanowicz wrote that when she finally could set up her own workshop, equipped with a lift for hanging Abakans, she was already around 40 years old. However, she quickly felt that everything that could be said in the matter of fabric and Abakans had already been said. She decided that she had succeeded in grappling with fabric[6]. Although Abakans — with their power of expression, eroticism and uniqueness opened a very tempting path for artistic exploration, she decided to abandon them and she proceeded to look for new means of expression.

Written by Julita Deluga

Translated by Ewa Tomankiewicz

The text comes from a catalogue accompanying the exposition: Magdalena Abakanowicz, Abakany, Galeria Starmach, Kraków, December 2015 – February 2016

[1]M. Abakanowicz, Nie lubię reguł [in:] Magdalena Abakanowicz, Centrum Sztuki Współczesnej Zamek Ujazdowski, Warsaw 1995, p.22.

[2]M. Abakanowicz, Abakany [in:] Magdalena Abakanowicz, Centrum Sztuki Współczesnej Zamek Ujazdowski, Warsaw1995, p. 28.

[3]Ibidem, s. 24, 28.

[4]J. Inglot, The Figurative Sculpture of Magdalena Abakanowicz. Bodies, Environments, and Myths, University of California Press, Berkley, Los Angeles, London 2004, p. 61.

[5]Compare: Magdalena Abakanowicz, Fate and Art, Monologue, Skira, Milano 2008, p. 38.

[6]Compare: Ibidem, p. 66.

![Magdalena Abakanowicz, Abakany [Abakans], Starmach Gallery, Krakow, December 2015 – February 2016, photo M. gardulski, Starmach Gallery](http://contemporarylynx.co.uk//wp-content/uploads/2016/04/11.-1024x682.jpg)

Magdalena Abakanowicz, Abakany [Abakans], Starmach Gallery, Krakow, December 2015 – February 2016, photo M. Gardulski, Starmach Gallery

Magdalena Abakanowicz, Lady, 1970/1980, 300 x 280 cm (fragment), photo Starmach Gallery

Magdalena Abakanowicz, 1960s, photo artist’s archive