Aneta Kowalczyk and Grzegorz Kosmala, Photo by Mirek Kania

While strolling along, or rather trudging through the dense crowd at Unseen fair few weeks ago, I was caught up by a modest stall with decent, yet elegant looking covers that seemed to not exactly fit in this eclectic, buzzing, all-in-one fair. There was something unsettlingly peaceful in these mostly black-covered books. A beguiling impression, as the stories told by each of them was at least ambiguous: soothing and distressing at the same time. The rare kind of stories that, although neither big, global, environmental, fancy nor political, have the power to drag your attention far out from rumbustious surroundings. If this already sounds like your type of stories, meet the people behind the bookshelves: an inconspicuous couple and publishers: Aneta Kowalczyk and Grzegorz Kosmala, who agreed to talk about their publishing: the BLOW UP PRESS.

Blow Up Press, Unseen Photo Fair Amsterdam

Blow Up Press, photo basel international art fair

AW: The name BLOW UP PRESS will be easily deciphered by anyone who is into Photography – connection to Antonioni’s movie is straight and immediate. Was it your plan from the very beginning to create a publishing dedicated exclusively to photography?

GK: Yes, that is right. That is actually quite interesting, as we have not been educated in photography, neither did we graduate any art course or school that could have possibly had pushed us towards photography. And we do not find it disqualifying or depreciating ourselves, because, on other hand, we kept our eyes wide open when it comes to our preferences towards visual language, technique or topics of the projects. Neither did we confine ourselves to documentary photography that was the first what we worked with when establishing BLOW UP PRESS in 2012.

AK: The idea of publishing books has been so deeply rooted in us since then. It is such an amazing medium, something that is definitely worth creating and spreading to the world. The thing about photobooks is that they are capable of telling stories equally well as novels do.

“Death Landscapes” by Hubert Humka

AW: Nevertheless, a photobook seems to be a difficult form, as it conveys narration through images in place of words. And although the form of a photobook or an artist book is not a recent one, these are still quite specific, niche forms. Actually, what is a photobook and how does it work?

AK: For me, a photobook is a living form that, like a narrator, is capable of telling a story. Apart of that, it is an artistic object itself that has nothing to do with, for example, a catalogue presenting images one after another. From my perspective, a photobook occurs when I feel that, despite lack of words and with images only, I am being led through a story that I understand and that is engaging me emotionally. And this means that I am not a passive viewer anymore, but I am actively responding to the story, what has nothing to do with a superficial aesthetic experience.

GK: A photobook reverses the relation text-image. What mediates the content is an image while text becomes only a supplement, unless it functions like in Hubert Humka’s book, the Death Landscapes. In this case, text is an integral element of the visual narration and adds to photography that has been the starting point for the whole narration. Simultaneously, here, the text’s role is far from a curatorial text. These are archival materials that matters because of their contents, authenticity and visual form. Still, these are the images because of the book is so powerful. And these were the images that led Hubert to reach to and use the archives.

“9 Gates of No Return” by Agata Grzybowska

AW: Hubert Humka is one of the artists you cooperate with. In fact, one can see some common features in the projects you have published. Is there any link between the photographers you work with?

AK: Our intention is to tell the stories that are not minor and that reflect the condition of man in the present, the condition of the reality we are living in, the relation between a man and their surroundings. Which does not necessarily mean that one day we will not publish something that is not grand or dramatic.

GK: Well, I think it is difficult to escape the fact that the subjects of our books are not very “light” ones: depression, solitude, addiction… It was a few years ago when it happened that all our books had black covers. Thus, during one of the photobook fairs in Madrid, our stall looked quite peculiar… When someone was approaching us, we were humorously welcoming them and introducing ourselves as the “most depressive publisher at the fair”. And even though, people were staying, looking through the books and buying them.

The first monography that we published was 9 Gates of No Return by Agata Grzybowska. This book tells about how fickle melancholy and solitude can be. The main characters are people, who, between 60’s and 80’s, of various reasons, decided to move and live in Bieszczady, mountains located on the south of Poland. Bieszczady was a secluded place by then, practically not inhabited. These people have been living there since then, frequently in very rough conditions, in the houses they built by themselves, without access to running water nor electricity. And now, after such long time, they do not have any possibility to come back to their past lives or the “normality”. They do not have families, nothing to come back to. So, what has seemed to be a peaceful resort, became a prison, in a way.

Hubert Humka, in his work, is asking a question why people become evil. Is this a particular intersection of time and place? The other question that bothers him is, if we are aware of the past of a place that witnessed an atrocity, do we perceive its landscape differently? Hubert gathered 13 different histories that happened in different places and in different time: from the World War I, to the terrorist attack on Bataclan Club in Paris in 2015. The book itself combines of archival materials and photographs of the places where these dreadful events took place, whereas the pictures were taken by Hubert on the very anniversaries of these events.

When it comes to Ilias Georgiadis, his story is a very personal one. In Over.State Ilias plays the main role in it, a symbolic one, as he represents a young man with universal dilemmas, but also inability to approach other people. He tries to overcome his own barriers with photography and a camera becomes a tool that enables him to create relations with people he meets.

Ilias’s story is similar to the one of Igor Pisuk. We worked with Igor on a very personal, autobiographic story too. Pisuk’s Deceitful Reverence tells about a man who struggles with alcohol addiction, depression and fears against the external world. He also fights with these with photography. Whereas the book documents 6 years of his struggle. And it is concluded with a happy end, as its last chapter is dedicated to finding love.

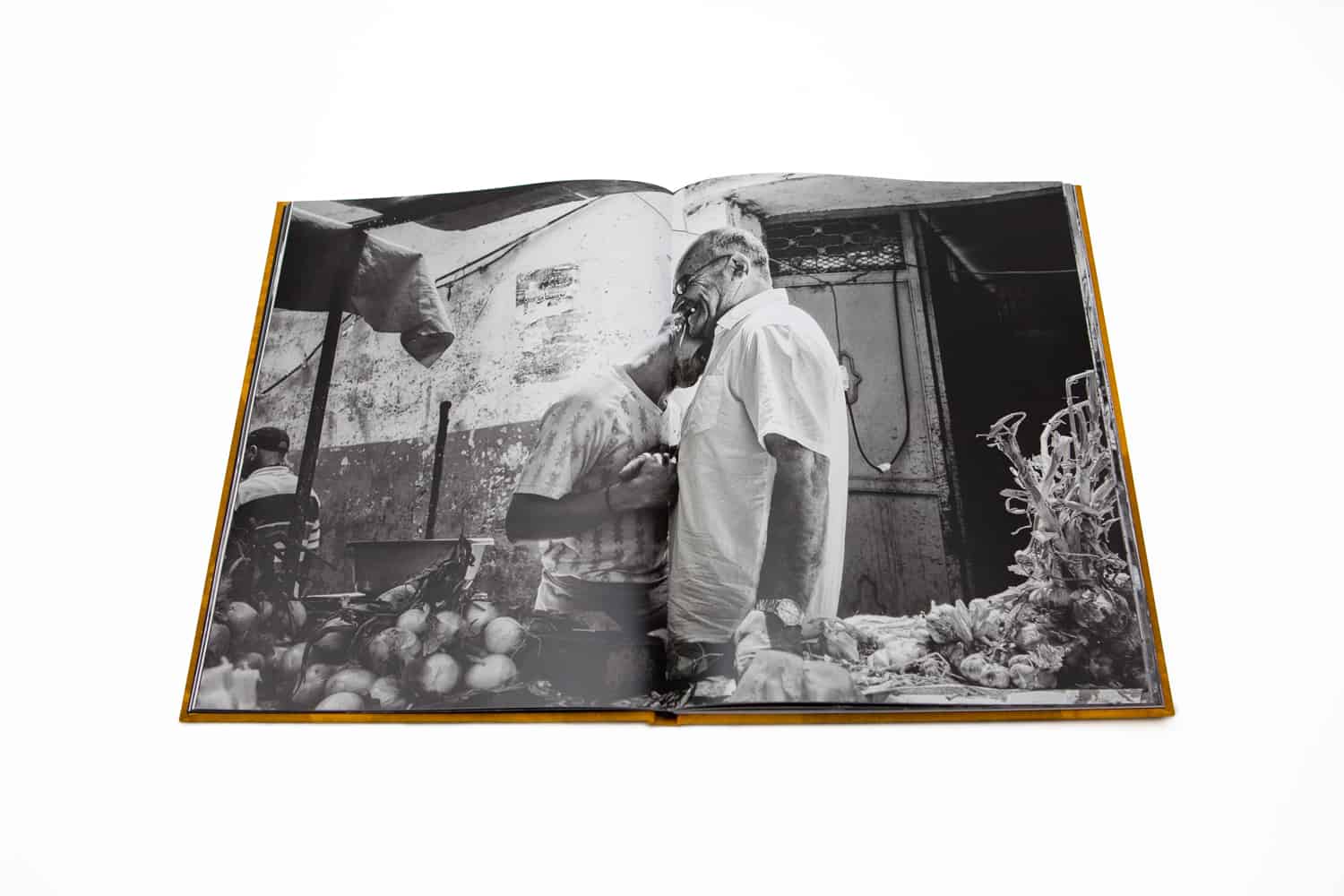

Which is on contrary to Luca Desienna’s My Dearest Javanese Concubine, that does not have a happy end, though it is entirely a love story. It happens between two people, two outcasts from Indonesia. Tira, born as a man, has always felt being and wanted to become a woman. Yet, she did not obtain the official permit to change her biological sex, thus she subjected herself to a series of illegal operations. However, this process was interrupted and stopped in a moment when it occurred that she is HIV positive. Nevertheless her situation, she did not resign from seeking for love. And she found one, Dayang: a person rejected by society alike herself, unemployed and homeless. They started to live together, in a tiny flat, barely 6 square meters of space. The book tells a story about their deep feeling and huge passion they had to each other, despite being weak, disfigured, sick and socially rejected. The story does not end up well as Tira eventually dies.

We also published books by Tytus Grodzicki and Lorenzo Castore. Tytus took an attempt to photograph his memories. In fact, the Deglet Nour is a story about memories. Tytus made a leap back to Algeria, where he used to live with his parents as a child, in order to photograph what he remembers. Meanwhile, Lorenzo Castore in his book Land, tells us about Gliwice, a small place in Silesia, the most industrialised region of Poland. His story is quite peculiar, as he narrates about a kind of a place that is little expected to have anything interesting happening there. Yet, in Castore’s photographs surprisingly a lot of action takes place.

“Deglet Nour” by tytus Grodzicki

AW: The photographers you work with frequently address you directly with a proposition of a project to be published. Otherwise than that, a book is a complex form: it combines of visual material that has to be edited and put into a desired format, printed on a paper that is also very important as it changes not only the colours and contrast, but also makes the book more tangible… How do you decide whether to cooperate with the certain artist and how does the process of working on the books look like?

AK: Well, it is probably not a normal situation, but we treat our books like our children… Each book requires different amount of time and effort as each is an individual project, so we treat it as such. For instance, Agata Grzybowska and Hubert Humka were working on their projects simultaneously to the books. Thus the visual material was being produced and provided to us consecutively. Thus the books were not a summary of their photographic work, but a pre-planned result.

GK: Still, the most important part is the history. It has to simply captivate us. When it does so, we start to think how to close it in a form of a book.

AK: Naturally, even a grasping story has to be well communicated. Thus photographs are crucial as well. These two have to be well balanced.

GK: Yes, all in all, we have to simply fall in love with the project. Otherwise, we will have a huge problem with spending long months working on it and encouraging people to buy it afterwards.

AK: Of course, publishing a book is not an easy process. It combines of multiple meetings, discussions. Basically, selection and edition of visual material is on my side. I am always asking for a complete set of materials, everything that has been created during the work on the project, with no selection nor edition. This gives me more understanding of how the photographer works but also gives me an access to a vast material. With Grzegorz, we are together selecting the material and, later on, consult the selection with the author.

GK: Yes, we always ask the authors to step aside from this process at the very beginning as they are often too tightly emotionally bounded to their projects. Of course, this does not mean they are entirely excluded from this process. As mentioned before, we discuss the selection altogether afterwards.

“My Dearest Javanese Concubine” by Luca Desienna

AW: Photographic market is often perceived as an environment, what seems quite accurate statement, as it certainly is a very well-defined community that can be found even a hermetic one. Who are the receivers of your books, are this exclusively people connected to photography?

GK: In a way you are right, it indeed is a closed system. However, I do not find it an issue. The truth is that somehow we manage to reach out to people from outside the photography-circle, by introducing our books to art fairs where you can find not only photography, but also illustration, graphics, design, etc. We try to reach out to people like ourselves: who are hungry for stories about other people that are inspiring, important, moving. These are usually people who consciously resign from what media offer nowadays, probably in order to really know and understand other human and their actions. Frequently these are photographers, people who are passionate about visual narration. This automatically determines the places where we appear with our books. Usually, these are bookstores, festivals or fairs dedicated to photobooks or artist books. Simultaneously, we are fully aware of the fact that we are not creating any sort of mass production. We have fitted in a niche and our books are also niche. Thus the number of published books never exceeds 1000 copies and frequently oscillates around 300-600 copies of the same title. What is sure is that people, who receive our editions are consciously looking for books, artistic objects that are not disposable. We are not publishing books that are designed to be looked through once and put back on a shelf. We produce books that are designed to come back to.

“Deceitful Reverence” by Igor Pisuk