One cannot discuss avant garde art without mentioning art manifestos; and indeed the beginning of the 20th century was marked with the publishing of art statements to such an extent that it seemed indispensable to present one’s artistic objectives in writing. In 1909, Tommaso Marinetti published Manifesto of Futurism, where he stated that “a roaring car that seems to ride on grapeshot is more beautiful than the Victory of Samothrace”[1]. Cubist, suprematist, dada and surrealist manifestos followed – to name only the most important ones.

The spirit of modernism helped people believe that everything can be defined and categorised, and the more you specify the easier to understand things become. Manifestos were also meant to help viewers accept new theories and formal novelties – the Western art world has never seen such a drastic aesthetical change as in the first half of 20th century. Vassily Kandinsky thought of artists as prophets who help to “move forward the ever obstinate carload of humanity[2]“. He saw them as pioneers of the new world, bringing modern discoveries to people – and in his opinion artists were chosen to explain and teach how to live in a new reality, point out possible dangers and ask the core questions about humanity.

We no longer believe in the modernist dream, but the feeling of a new world being created in front of our eyes still persists. The contemporary art world reflects the ubiquity of new technologies by incorporating them into art pieces. The traditional form of a manifesto may be outdated, but its purpose never goes out of date.

Metahaven – Black Transparency, 2013

Metahaven was started by Vinca Kruk and Daniel van der Velden in Amsterdam. It is hard to find one word to describe it – it is more than a studio, but not really a collective, engaged in “Aesthetics, Politics and Research” as their website announces. Sarah Hromack, in an article written for Frieze.com, states that they could be considered “tenacious visionaries who work across multiple platforms to create a broad variety of functional objects, as well as a prolific amount of insistent, manifesto-like critical and self-referential writing[3]“. They gained recognition after designing a volunteer branding exercise for Wikileaks in 2011 – a series of T-grey shirts with the organization’s name on it, together with scarfs printed in camouflage-like patterns – an ironic reference to a luxury good.

In “Black Transparency” the topic of massive surveillance is discussed again, together with a discussion of the threats to democracy and ways to survive in the world where nothing is private anymore. Found footage recordings from war zones are mixed with idyllic vernacular videos of children playing on a beach resembling the way the banal and the important coexists on the web. In a steady, unemotional manner a female voiceover reads a disturbing text describing what it means to live in 21st century.

“Silence and invisibility are the principal currencies of our utopia.

Soon, everything will be a secret.

But what about ourselves? Aren’t we silent ourselves?

We haven’t said anything in a long time.

We battle.

We throw Molotov cocktails, fight the police, and dance on the wings of a government airplane.

We look into our phones which look into our lives.

The bare possessions of a non-person living in a non-place.

A laptop.

A backpack.

A night with friends.

An on-and-off relationship.

A temporary job.

A trove of secrets.”

The full transcription of the text is available at https://pastebin.com/UMNv2EXf

Black Transparency from metahaven on Vimeo.

Morehshin Allahyari & Daniel Rourke – The 3D Addivist Manifesto, 2015

The #Additivism movement considers the 3D printer as a profound metaphor for our times: “We declare that the world’s splendour was enriched by a new beauty: the beauty of crap, kipple and detritus.” 3D fabrication technologies are the site of a common exchange between disciplines and forms of materiality, which can lead to creating cyborg bodies and cross-species organisms: “We call not for passive, dead technologies but rather for the gradual awakening of matter; the emergence, ultimately, of a new form of life.” In an endless sea, various 3D models float like unexplored islands: cartoon characters, hardware tools, ancient Greek sculptures – everything mixed, lifted or degraded to the same level of importance. The aesthetics are secondary to the need for creating something unprecedented. A machine-generated voice calls for artistic speculation on matter and its digital destiny, the introduction of errors, glitches and fissures into 3D prints to liberate the process and enabling biological and synthetic things to become each other’s prostheses. “For only Additivism can accelerate us to an aftermath whence all matter has mutated into the clarity of plastic.”

The full text is available at: http://additivism.org/manifesto

The 3D Additivist Manifesto from Morehshin Allahyari on Vimeo.

Mendi + Keith Obadike – Black Net. Art, 2001-2003

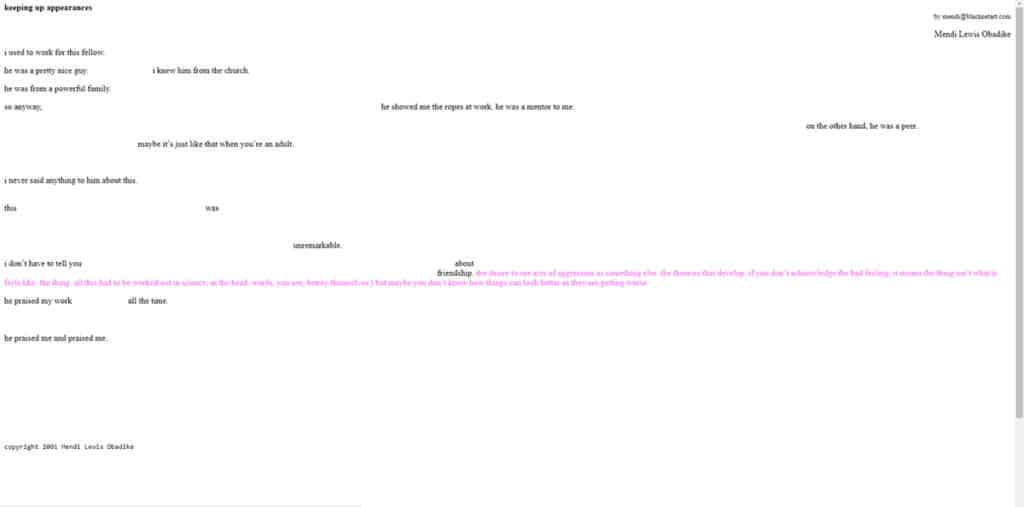

“We did not feel that the net was a colourless space, but rather that whiteness was being set up as the default” wrote Mendi Obadike. In the series of works called “Black Net. Art”, a Nigerian American couple proves that both the digital and the real world differentiate race in a similar way. In “Blackness for Sale” (2001) Keith’s Blackness was listed on eBay as an item for sale with the description: “This Blackness may be used for creating black art” and “The Seller does not recommend that this Blackness be used in the process of making or selling ‘serious’ art”. As an Item #1176601036 it reached 152$ in 12 bids until it was removed by eBay four days later for being inappropriate. In 2002, they created “The Interaction of Coloured” website meant to specify a hexadecimal colour code for your skin shade. “Wouldn’t it be refreshing to get trustworthy colour info like John Smith, #FFFFFF (read: true white) when you receive an email?” “Keeping up Appearances” (2001) is a website with a simple text written in black letters on a white background, and only when you begin to move your cursor around do hidden parts appear in vivid pink changing the innocent sentence into a diary of the sexual abuse of a black girl by a white man. Taken as a whole, the actions can be understood as an attempt to reformulate net art with race as a central concern.

Keeping up appearances, Mendi + Keith Obadike

Billy Gallery – What Really Matters?, 2012

Billy Gallery was created in 2011 by Paweł Sysiak and Tymek Borowski as an online gallery with a mission to tackle avant-garde culture on the internet. In “What Really Matters?” its creators approached a wide spectrum of people to ask them the titular question, and they had to answer in the form of a short film. All of the 13 videos were later published online – even if they reveal the answer only tangentially, they show the gravity of the question. Each of those videos approaches the topic differently – some are straight forward, some absurd or funny. Rafał Dominik in a colorful, simplified animation tries to answer the question with infographics and algorithms. Daniel Mizieliński, a renowned Polish designer and illustrator, unravels his “Hell Yeah No” technique – only do things that make you say “hell yeah” and say no to everything else. Sławek Pawszak presents a live photograph of a group of people with the title “All that really matters is friends and family”. Trying to “cut out the layers of sophistication in culture”, which was the authors’ intention, resulted in quite elaborate answers.

Elena Artemenko – Manifesto Generator, 2011

The “Manifesto Generator” project is based on a computer program that generates new art manifestos in real-time, based on the database of a hundred foundational art manifestos of the 20th century. Each new manifesto is printed, and announced simultaneously, by the computer using a text-to-speech facility. Artemenko explores the ways of creating and evincing new ideas and trends in the art world. The postmodernist ideas of remixing and synthesizing old ideas to create new ones are literally brought to life in “Manifesto Generator” – a new world doesn’t have to be constructed from scratch, we can just tinker with it based on existing elements.

Elena Artemenko Manifesto Generator

[1] Tommaso Marinetti, The Founding and Manifesto of Futurism, 1909 / http://www.italianfuturism.org/manifestos/foundingmanifesto/

[2] Vassily Kandinsky, On the Spiritual in Art, Solomon R. Guggenheim Foundation New York City 1946, p. 17

[3] Sarah Hromack, What is Metahaven?, Frieze.com, 2015 / https://frieze.com/article/what-metahaven