The expressionism movement in European art originated in Germany, so it is natural for us to automatically connect the two. The term “expressionism” was first used in 1901 by Julián-Auguste Hervé, the French painter who gave this name to a series of his paintings exhibited at the famous Salon des Indépendants in Paris.

Artists who were part of the expressionism movement challenged the existing reality and tried to emphasize phenomena that were exceptional, distorted and pathological. They presented deformed reality, which served as a vehicle for communicating their subjective perspective on what was around them. Besides malformed human figures they painted distorted landscapes, cities and deformed elements of nature. They also used symbols that were supposed to help the audience reflect on the dark realms of human subconsciousness. Later on they enriched their works with new points of reference, e.g. the experience of war and opposition towards fossilized structures present in social and political life. Their genre paintings usually had a warning or a moral hidden inside and the thinking behind the act of their creation was to find a purpose and experience moral revival. Common experiences, as well as exchange of thoughts and journeys on the other hand gave rise to new aesthetic inspirations. In other countries, where expressionism flourished later on, additional elements of the style were clearly visible. In Poland one such local addition was religious mysticism and omnipresent hope for regaining state independence.

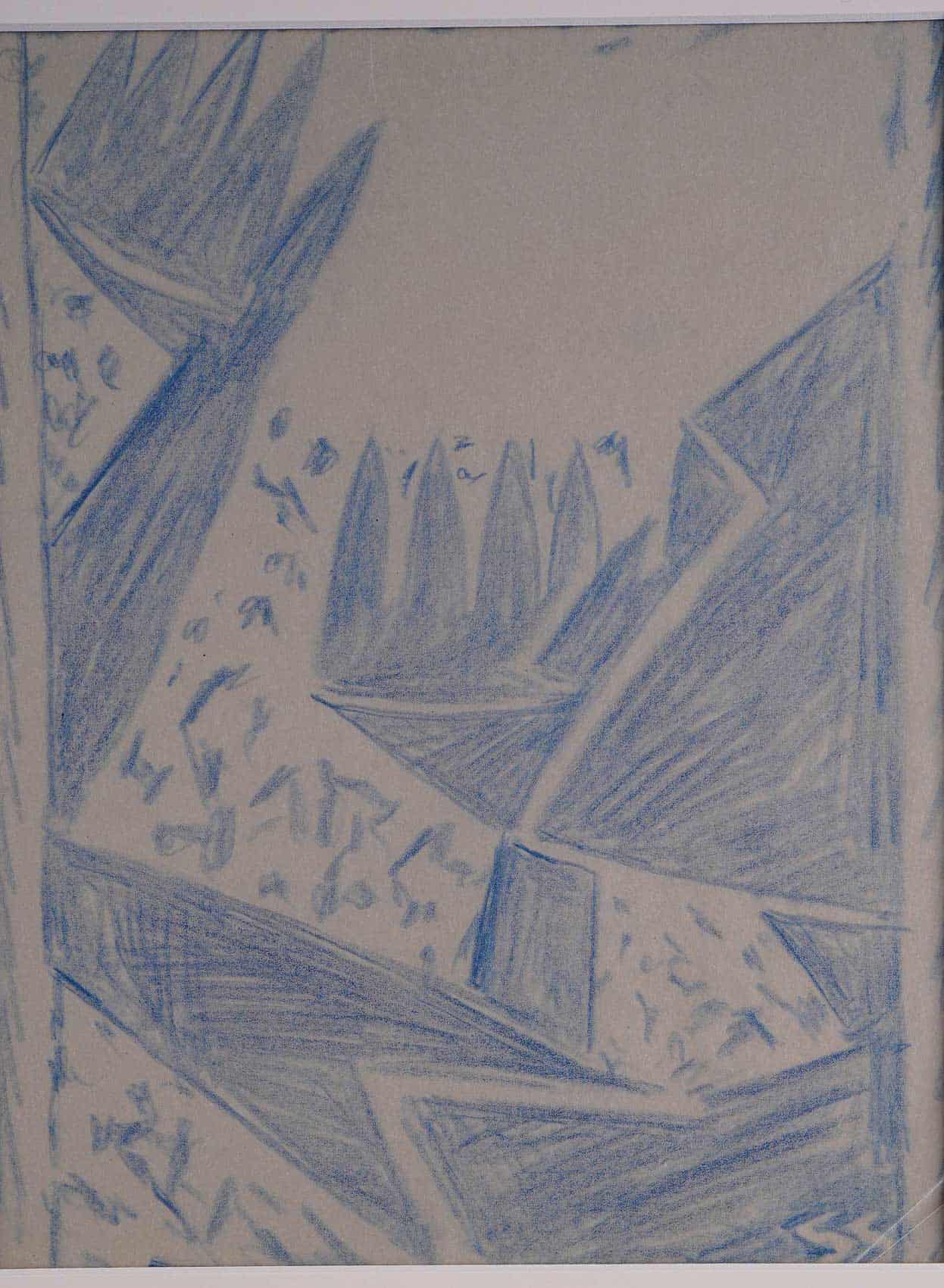

Stefan Szmaj, Self-portrait, 1916, Linocut, paper; 16,9 x 13,8 cm

A perfect example of a Polish artist who followed the principles of this movement and added the above-mentioned specific elements to his works was Stefan Szmaj. Currently his works can be seen at Olszewski Gallery in Warsaw. Stefan Szmaj was a graphic artist and a painter. In 1917-1918 he created a series of expressionist linocuts. I had an interesting conversation with Urszula Dragońska about the works and achievements of Stefan Szmaj. Urszula Dragońska is an art historian specializing in early 20th century art who participated in the creation of the catalogue of works by Stefan Szmaj.

Dobromiła Błaszczyk: What were the artistic inspirations of Stefan Szmaj? How much did he really know about expressionism? Was he in contact with expressionists in Germany? How did he become familiar with their works?

Urszula Dragońska: Works of Stefan Szmaj were definitely influenced by his experiences as a student and the fact that he spent these years in Berlin and Munich. Although he studied medicine, and art was by no means the purpose of his stay in Germany, the vibrant artistic community in both cities quickly drew him in. German expressionists published their graphic compositions in literary and artistic journals “Die Aktion” and “Der Sturm”. These graphics had an enormous impact on the young Stefan Szmaj and served as a stimulus for him to start creating graphic works as well. The very first member of his audience was Stanisław Przybyszewski who met Szmaj in Munich. Stefan Szmaj was an entirely self-taught person when it comes to visual arts, so being noticed and appreciated by Przybyszewski meant the world to him. The young artist drew extensively on Przybyszewski’s philosophy and views, which we can see in such works as The Portrait of Przybyszewski and The Kiss. Another important source of inspiration was his relationships within the Bunt Artist Association. Szmaj was a member of the association since 1918. If we analyze his works created after this year, we would notice numerous similarities e.g. with works by Jerzy Hulewicz, namely the choice of topics, composition solutions and graphic techniques. Most probably it was the period when Szmaj established personal relations with the representatives of German expressionism who published in “Die Aktion”. This was possible thanks to Stanisław and Margarete Kubicki who liaised with the avant-garde artists from Berlin and facilitated their contacts with avant-garde representatives from Poznań. This binational married couple (he was from Poland and she from Germany) assisted in cooperation between Poznań and Berlin. The result of these activities were special editions of “Zdrój” and “Die Aktion” journals, which presented works and achievements of artists from the other side of the border. There was also an exhibition of works by artists from the Bunt association organized in Berlin.

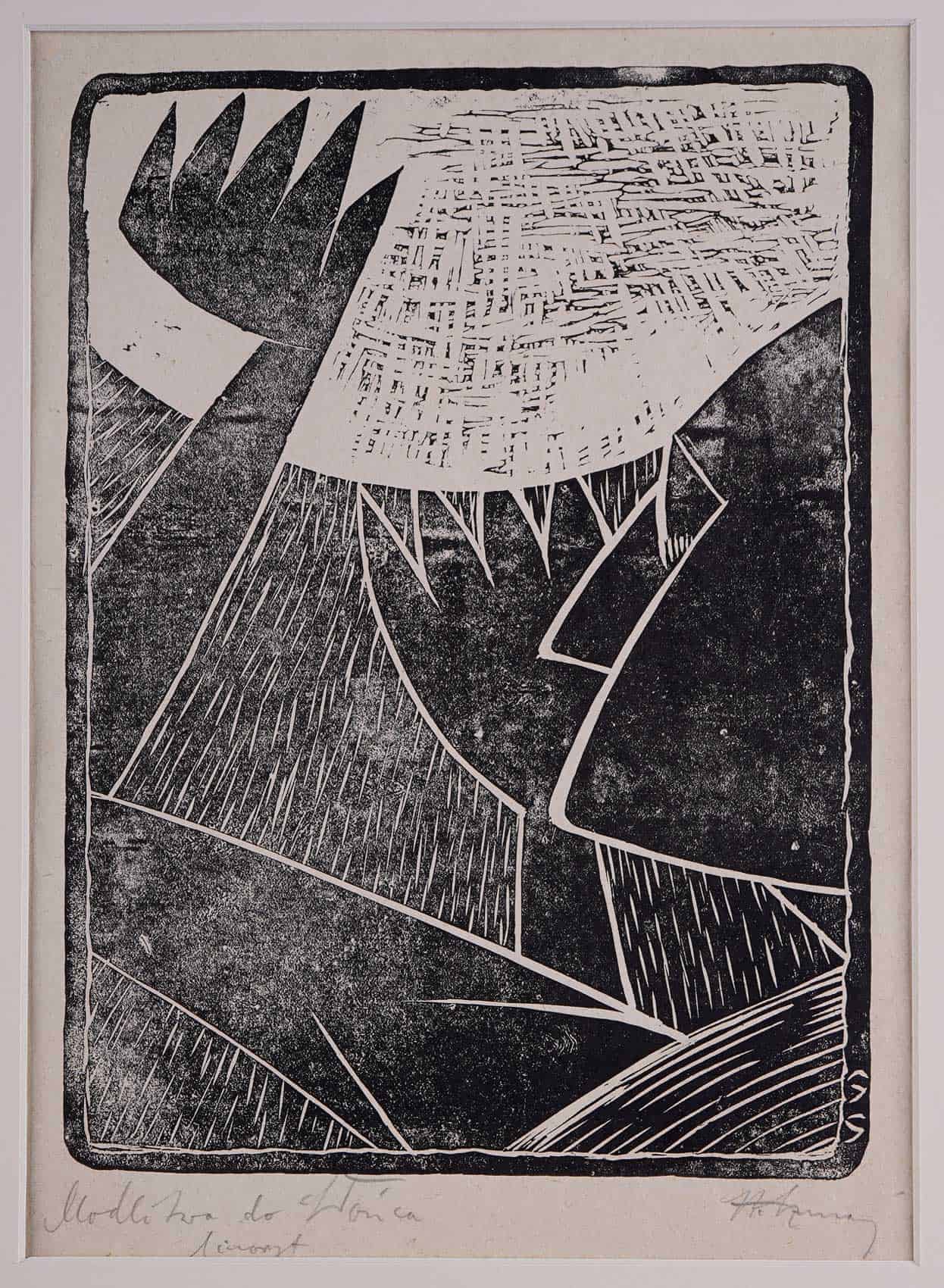

Stefan Szmaj, Kiss, linocut, papier; 17,4 x 15,7 cm

DB: Why are works by Stefan Szmaj so exceptional and unique when compared to works by other expressionists in Poland and Germany?

UD: Before we touch upon works by Stefan Szmaj and their uniqueness within the oeuvre of Polish and German expressionists, let’s try to list some features characteristic for the international expressionism movement. About the time when World War I started, in many Central European cities, such as Berlin, Dresden, Munich, Prague, Budapest and Poznań artists who shared the vision of new art that would deny achievements to date and left-wing political views were drawn together and formed groups and associations. This is obviously a huge simplification because groups and artistic circles differed in many aspects. Nevertheless, many researchers emphasize that the international community of artists who reacted to current events in a similar way commenced at that time. Bunt association and, naturally, Stefan Szmaj as its member, was a part of this wider community, which was manifested through mutual relations, similar mode of operation focused on reaching the public through a journal, exhibitions and meetings, as well as similar topics elaborated on and stylistic techniques selected. The main difference between expressionism in Poznań and in Germany was the emphasis of the fight for Polish independence. Apart from the atrocities which cannot be adequately described, World War I brought hope for changes and a belief that it was possible to overthrow the existing political order. Artists from Berlin who published works in “Die Aktion” and “Der Sturm” wanted to get rid of the emperor, whereas members of Bunt wished Polish society had been revived and had lived within the borders of an independent state. Szmaj and other artists from this association personally supported activities aimed at regaining freedom and presented this issue in their works. Works by Stefan Szmaj, for example Saint Francis presented at Olszewski Gallery or The Poplars series are also interpreted in reference to these aspects.

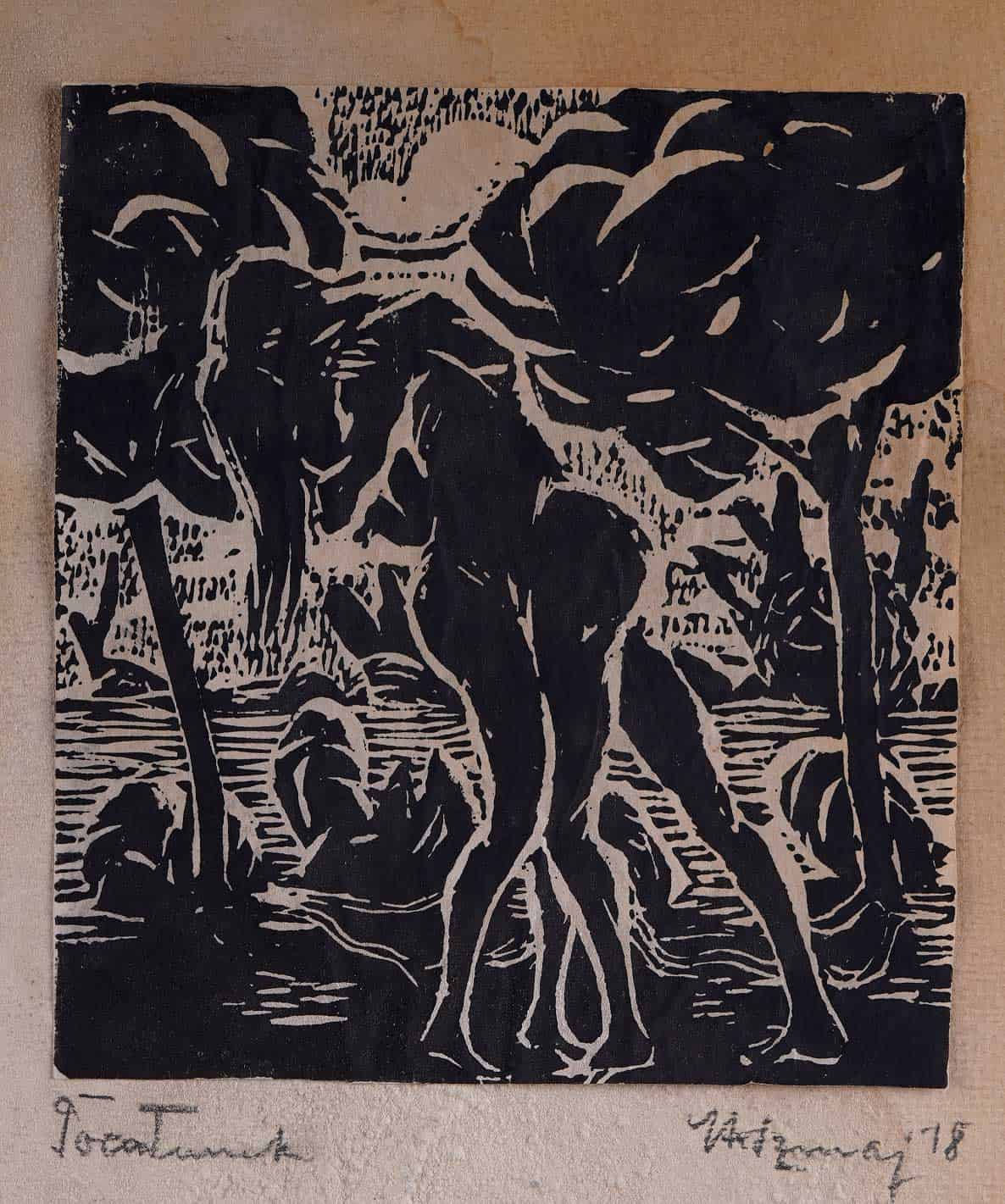

Bunt association was by no means uniform and unanimous. It only existed for a short period of time, mostly due to differences in views and opinions among its members. Szmaj himself definitely belonged to the less radical fraction which continued on the path of figurative art and did not revert to purely abstract works promoted by Stanisław and Margarete Kubicki. He differed from his colleagues in terms of his attitude to nature, which was a crucial part of his numerous compositions. We can see it clearly in the cycle entitled The Poplars (mentioned before), in which the artist shows unity between the world of humans and nature and presents how they both are affected by traumatic experiences of the world war. No other artist from the Bunt association studied his own image as much as Stefan Szmaj did in his numerous self-portraits created as years passed. In those portraits he thoroughly analyzed his physiognomy and psyche.

Finally, I would like to emphasize the fact that he chose linocuts as the main means of expression during the period he spent in Poznań. This was an intentional choice made of inspiration with the German expressionism. So, the rationale behind this decision were not purely connected with the need to provide graphical material for the “Zdrój” journal, as it was for many expressionists from Poznań.

DB: The selected graphic techniques emphasized the expression and dynamics of a composition. Thick lines, sharp cuts and angular lumps. Another asset was the possibility to duplicate elements created using these techniques and to reproduce the composition. Thanks to this, it was easier for the works to reach wider audience and this in turn made the art much more democratic. Szmaj mostly used linocut and not woodcut. What specifically did the technique he chose have to offer?

UD: Linocut seems dominant among graphic techniques used by the majority of members of the Bunt association who published their works in “Zdrój”. This technique was actually a new phenomenon among various forms of print, but it gradually gained popularity in the late 19th and early 20th century. It quickly turned out that linocut can be a cheaper substitute for woodcut and the final effects of using both techniques are similar. Both of them allowed the artist to easily obtain contrasting combinations of black and white surfaces, dynamic cuts in a material visible in the print, thick lines defining contours of the image and simplification of presented forms, which were the effects that expressionists liked and were eager to use. In addition, it was significantly easier to cut a composition into linoleum than into wood, which was a much harder material. The matrix prepared in this way could be used to make prints both in a workshop and on a printing press next to a text to illustrate books, papers and magazines. This aspect was extremely important for expressionists from Poznań who really wanted their works to reach wide audience.

Stefan Szmaj, Linocuts 1916-1920, The Regained Independence of Expression

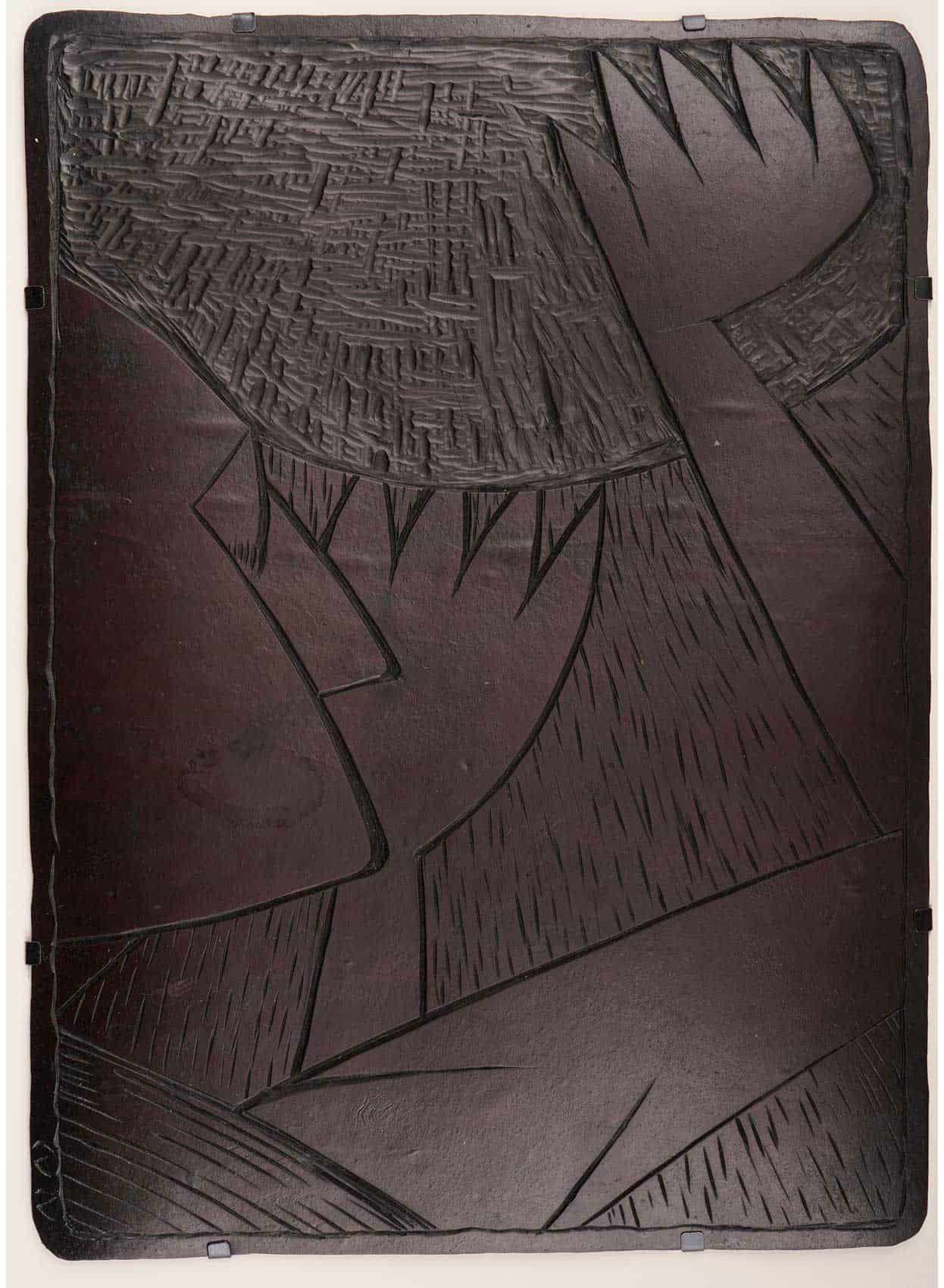

DB: It does not happen very often that an exhibition features not only graphic prints, but also sketches, matrices and calked final pictures which served as drawings for slightly altered graphics. Why is it so? Are the matrices not being preserved? Why are there so many matrices at this specific exhibition?

UD: Indeed matrices are rarely presented at exhibitions and there are numerous reasons for this. A matrix is one of the tools needed to create the final work of art, i.e. a print. It is this final “product”, not the tool, that is intended to be presented. It was only in recent decades that matrices started to be perceived as the final result of work by an artist and relevant activities aimed at presenting them as well took place. Woodblocks, metal and linoleum plates and lithographic stones are a fantastic source of additional information about the methods a graphic designer uses, his/her skills and approach to matter he/she works with. They allow us to better understand the creative process which culminated in the creation of an original print. If they are presented at an exhibition it is usually with this purpose in mind. There are not really a lot of graphic matrices preserved to this day. Most of them were destroyed during printing on the press due to the pressure force. If possible, in order to spare on material they were often used for the second time to create another matrix. It often happened that the creator of such matrices instructed others to destroy them after a certain number of prints were made, in order to limit the number of prints released. The preserved matrices are with us to this day thanks to people who appreciated their artistic value and saved them from destruction. Sometimes unauthorized prints were made by those people, whose value was much lower than the value of the authorized ones on the artworks market. The case of matrices by Stefan Szmaj is indeed exceptional. The preserved workshop has added replicas of those matrices, which the artist did not have at his disposal anymore for various reasons. Everything survived the passing of time as part of the family collection and is now extensively researched and frequently presented at exhibitions. Olszewski Gallery also decided to get involved in such a project, thanks to which we can enjoy this intriguing exhibition until 15 May 2019.

Edited by Lisa Barham

Stefan Szmaj

Linocuts 1916-1920. The Regained Independence of Expression

Olszewski Gallery, Warsaw