Paweł Kowalewski, photo: Andrzej Świetlik

Paweł Kowalewski is the founder and former member of the Gruppa art collective and an iconic figure of the 1980s Polish arts scene. Created during a period of political transformation, his works provide a unique and vital commentary on reality in the Polish People’s Republic. He can be defined as a post-conceptual artist who sensitises his audience to what surrounds them. A rebel among visual artists, university lecturer and poet. He grew weary of the mainstream, but he can do nothing to remove his name from the Polish art wall of fame. One of his works has been recently seen and admired in Venice, the city which just inaugurated the 2019 Venice Biennale. It is worth getting acquainted with this extraordinary artist who has a true gift of penetrating into our everyday reality and formulating his manifestos based on bits and pieces extracted from the existing plethora of events and phenomena.

Dobromiła Błaszczyk: The 1980s was the time when Gruppa was born out of the idea that you could do anything you wanted in art. Back then you decided to create paintings and get involved in performance art. What was the reason for this choice?

Paweł Kowalewski: I painted pictures with elaborate titles, wrote articles for our journal entitled “Oj dobrze już!” [It is fine now!] and participated in events and recitals organised by Gruppa. I think that the reason for this diversity was the fact that I lived in a state with a totalitarian regime that manifested itself in every aspect of our lives, deprived us of any intimacy, distorted literary works and made visual artists prepare works that were always in line with the official ideology. The change of mediums allowed me to report on my experiences with a substantial degree of credibility and freely comment on situations from my past. I never wanted to be a part of the official art scene which was directly influenced by the state to such a great extent. I was extremely annoyed with all the state authorities’ attempts to define trends and directions in which art was to develop.

Gruppa was never a uniform platform, but what united us was the fact that our works were never indifferent. I earned a distinction for my diploma in the field of visual arts, despite the fact that my diploma project was strongly criticised by many renowned professors. They questioned my approach and claimed that what I did went against painting as such. In fact, that was never the case. One cannot have control over art. Art must always stay unrestricted. At the very beginning, Gruppa and I as its member organised a lot of performances. We were convinced that although we could use painting, photography, film, sculpture and performance, or write literary pieces, what mattered most was the intended message. Therefore the fact that we are pigeonholed by art critics as representatives of the Neue Wilde movement is an oversimplification from the point of view of the history of art. The programme of Gruppa was mostly based on debates between me and my colleagues. We ardently discussed which words and means of expression we should use to present the intended content to the audience. Only later did the painting division assumed a dominant role in our group. When communism gave in to capitalism in the 1990s, we needed to deal with materialism as our new reality. I did not want to create artworks for the sake of making a living. So, this was a decisive moment for us when we decided to part our ways.

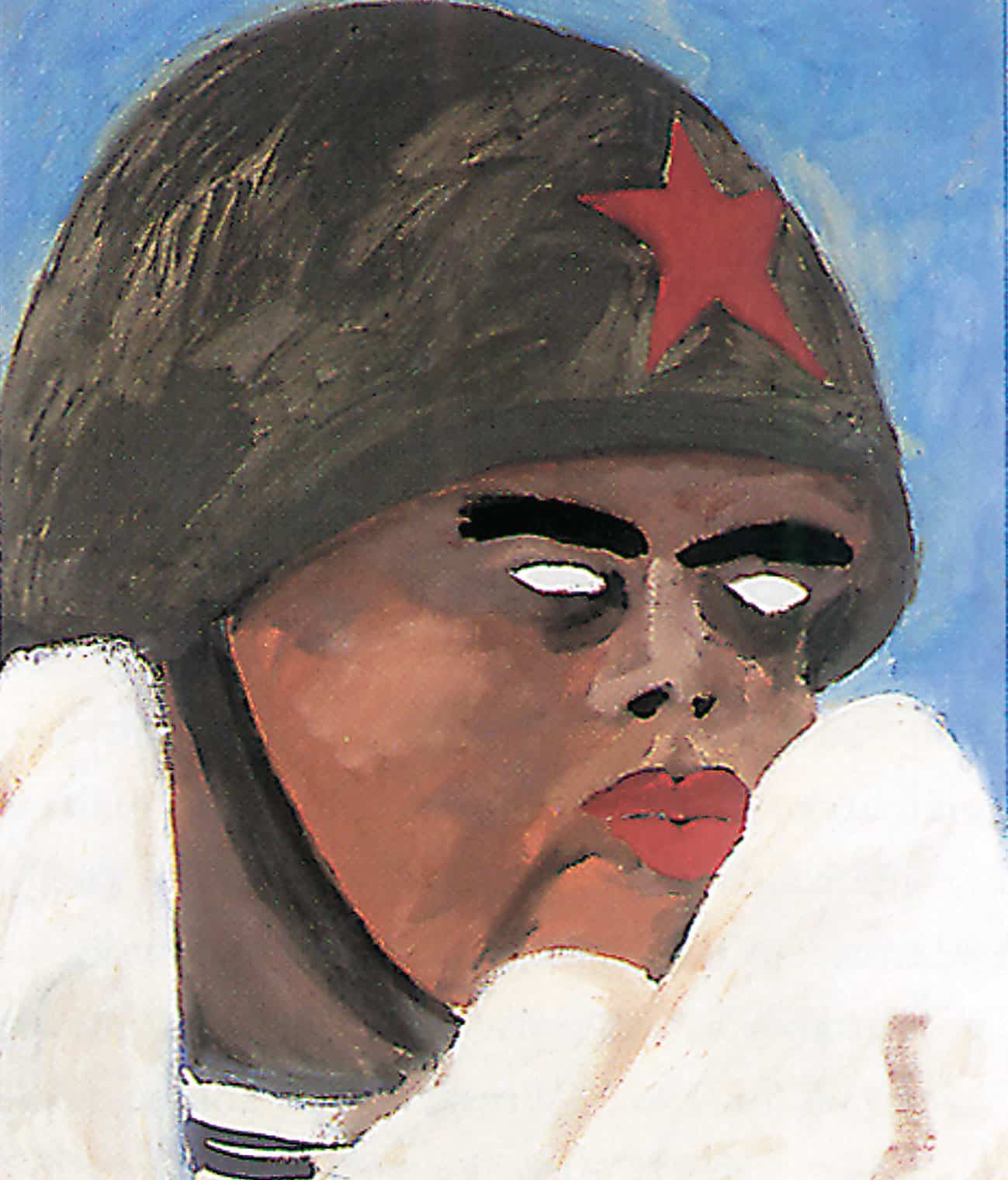

Paweł Kowalewski, “Mon chéri Bolscheviq”, 1984, oil on canvas, 100 x 81 cm

DB: Is it true that during one of your performances, you spilled Soviet perfume that was in a gallery?

PK: We did this during an exhibition entitled “Chłodny Jeleń w Powidle” [trans. “Cold Deer in Jam”] (1987). This performance was actually reminiscent of the Movement Academy (Akademia Ruchu). We wanted to influence our audience’s feelings in a shocking and straightforward way. We wished to go beyond all that you can achieve through painting. On another occasion we read poems to people and continued until the last visitor exited the gallery. We based activities of this kind on many different contexts – sociology, psychology, literature. We were keen on going beyond our comfort zone and making our audience do just the same. We were also fighting to eliminate the border between the form and the medium. A publication about Gruppa will soon be released. It will be a perfect source for learning more about our actions, campaigns, poetic letters and scripts. It will provide a significant number of archival materials gathered in one book.

DB: Tell us more about the concept of “personal or private art” which you mention so often.

PK: Personal art has neither a defined form nor a dedicated medium. Its message is exactly what an artist wants to communicate. The language which such art uses turns into an integral part of the work. I give up on researching formal aspects of art and trying out possibilities offered by a given medium. Instead, I focus entirely on conveying what is on my mind. I want to emphasise that I do not aim to present worthless reports or tawdry aesthetic mush. What I really strive for is freeing myself from the models of convention and the merely decorative functions of artworks. I have a longing to consciously look through the imaginary window into my inner self. Art is not a mere embellishment of our lives. Categorising it as such would deny its freedom. This is how I filter the world through my own self. For many years I have been keeping notebooks which have become the inspiration for a whole series of paintings and literary pieces. There is, however, neither time nor space for polishing it all up, playing with colours and pondering over forms. All that can be found there is a story about our nervousness, carefulness and emotionality. In this way I document reality after it is processed in my subjective sensations. Many important works were created on the basis of these notes, for example: “Pięści w kieszeniach, czyli bardzo wkurwiony robotnik” [Fists in pockets or a pissed off labourer], “Zdzicho skacze co noc z butelkami z benzyną” [Zdzicho jumps every night with bottles full of petrol] and “Ja zastrzelony przez Indian” [Me shot to death by American Indians].

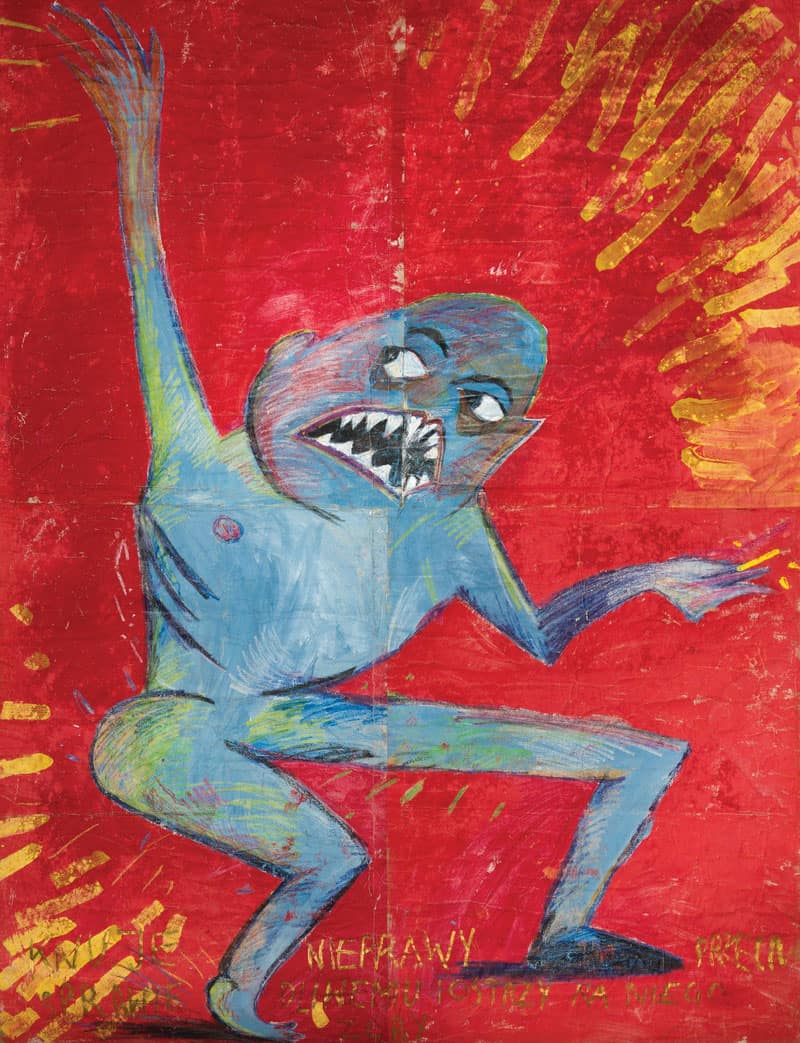

Paweł Kowalewski, “I have seen the wicked in great power, and spreading himself like a green bay tree”, 1985, acrylic on paper, 250 x 180 cm

DB: These notebooks are not just sketches and basic materials which provide the basis for subsequent works. They are independent works of art themselves. Would polishing them up produce a falsified picture of who you really are?

PK: It definitely would. Authenticity is key here. One way in which I try to make my works authentic are their poetic titles. I already want to tell something specific, convey a message in them. I want my viewers to instantly recognise the concept beyond a given work. When I think about paintings created by members of Gruppa I find that we could not have existed without words. They were far more important than any pompous academic narration. I could discuss the works and ideas of Kant and Bergson with my colleagues for hours. Sometimes our discussions about literature transformed into fist fights. This exhilarated us and kept us going. Perhaps this is why our paintings were so distinctive.

DB: The titles of your works sometimes served as spiritual manifestos.

PK: When I read the Book of Psalms in the 1980s I discovered that art is indeed timeless. Poems written over two thousand years ago perfectly related to the reality of the period in which I was reading them. I had no doubt where justice was. This was my spiritual realm and an intensive existential experience. I decided to illustrate and describe it. The authorities at that time killed people who called for peace and mercy. What I wanted to paint was the omnipresent terror, fear and vileness of the crimes that they perpetrated. Every painting from the “Psalms” series (1984-1985), which was inspired by the Books of David, was accompanied with quotations which described the reality we had to live in. „For many are called, but few are chosen”, “Trust in the Lord, and do good; so shalt thou dwell in the land, and verily thou shalt be fed”. These paintings present topics which are relevant nowadays and evoke mixed feelings. “I have seen a wicked, ruthless man, spreading himself like a green bay tree”, can both be a reference to the current situation of Poland and the United States. The activities of Gruppa coincided with the events which were dramatic for entire Europe. These events posed a threat to people’s lives and their right to existence. I used quotations from the Psalms since they describe values which are timeless and I really wanted to remind my audience of them. What used to be controversial and implied political subtexts thirty years ago, stirs the same emotions nowadays. The universal character of my works has always been extremely important to me and I put a great emphasis on individuals, autonomy, worldly matters and temporary reality. In general, my works tell the audience that we find ourselves here and now and the choices we make now shape the future. The future cannot be separated from the past.

Paweł Kowalewski, “Many are called, but few are chosen”, 1985, tempera on paper, 237 x 182 cm

Paweł Kowalewski, “The wicked plotteth against the just, and gnashets upon him with his teeth”, 1985, tempera on paper, 245 x 179 cm

DB: When you presented “Psalms” in Poland, the artistic community chaplain removed them from the church. It is claimed that he did it on request of the congregation. Is this true?

PK: Back then, churches were among the few venues where artists could present works of art not altered or influenced by the censors. Artists and the church had a common goal at that time, so collaboration between them was flourishing. This synergy had an enormous potential, which, unfortunately, was wasted later on. It is regrettable that such a powerful patron of artists gave up on this circle of activity. The sacred is a tempting area of activity for artists after all. It is unbelievable that since the times of Matisse nothing was done to encourage artists to delve into the sacred. The Polish artist Jerzy Nowosielski combined these two worlds. When I look at my students I get the impression that they categorically deny the possibility of including the spiritual world in their creative quest. But whenever you say “no” to something you explicitly place yourself in favour of something instead of being perceived as neutral.

DB: Does your art serve as a political commentary?

PK: I have never made explicit references to politics in my works. What I can confirm is that I feel contempt for all totalitarian regimes, and I am in definite opposition to imposing the official way of thinking, breaching human rights, discrimination and racism. These are all things I am not able to accept. I used to live in a state where everything I just mentioned could be experienced on a daily basis; therefore I would betray my own feelings and beliefs had I not been protesting against the system. My painting “Mon cheri Bolscheviq”, which became an iconic work of the visual arts of the 1980s, features a man with a red star on his helmet, lips arranged as if ready for a passionate kiss, and eyes showing no emotions. In this way I showed the communism I experienced – ruthless and full of criminal activities. There is a second “Bolscheviq” painted in 2005, which presents the face of Vladimir Putin. It shows that the stories from the past and the present are closely interconnected and I am an eager observer of all these. Both works have a political background, but for me they serve as a personalised account of the dark times and everyday reality which surrounds us all. Let’s just mention a signpost reading “Europeans only” that is exhibited at the Apartheid Museum in Johannesburg…

Paweł Kowalewski, “Totalitarianism Simulator”, 2012, installation in Propaganda Gallery in Warsaw

DB: You make your audience sensitive to the surrounding reality by means of your works. In 2012 you created your famous “Totalitarianism Simulator”. Could you tell us something more about this project?

PK: Those who entered the simulator were shocked and disturbed when they got out. Disbelief could be seen in their eyes. In this installation/machine I combined oppression and explicit images of crimes committed by a totalitarian regime with illustrations presenting a regular, happy existence. A viewer who entered the simulator unwittingly became a participant of tragic events because he could see in the selected video frames his picture taken before he found himself in the booth. Inside the booth there was an armchair and those sitting in it watched images of idyllic life during the time of Nazi and communist regimes. Subsequent frames showed jubilant people strolling along the streets, deeply engaged in conversations and people drinking beer in pubs. In the background, however, they could see portraits of Hitler and Stalin. At that time nobody had annexed the Crimea yet but the war in Syria already was in its early stage. This is how the show in the simulator ends – with a picture of a street in Aleppo. The viewer was watching his own face surrounded by everything I just mentioned… Specially selected materials were used to build the simulator and the additional stimuli of the scent of rubber, the stink of tar paper and pitch, darkness and isolation added to the audiences’ sense of genuine oppression. The visitor could test his own reactions and behaviours in a simulated hazardous setting. After all, we are left totally alone in the face of totalitarianism…

DB: What did you intend to achieve through this work?

PK: It would be ideal if we all had enough time and resources to prepare for upcoming danger, but this never happens in real life. Treacherous forces come upon every one of us individually. When this happens we have to make a choice on our own whether to go right or left, or maybe to say “no”. How many people in the world are dying in their fight for freedom just as we are safely sitting here and discussing visual arts? There were countless occasions I heard people say that in Europe we have been living in peace for an extremely long period of time. But what about Sarajevo, Yemen and Ukraine? These ominous events take place so close to us. One may say that what I did was deeply politicised but for me bringing these issues to light represents my human nature.

Paweł Kowalewski, “Europeans only”, work from the cycle “Not allowed”, 2010, lightbox, 100 x 70 cm

DB: You presented an exhibition titled “Moc i Piękno” [Strength and Beauty] in Israel in 2015. It was about women who survived the Holocaust and the starting point for the selected works was the biography of your mother. In what way does this series of photographs complement your other artistic activities to date?

PK: You can measure time by making yourself aware of how many things people have already forgotten. Subjective memory is fragile and uncertain, therefore we should duly care for our collective memory. The “Moc i Piękno” [Strength and Beauty] series communicates to the audience that there are no oblivious zones. Beauty, no matter what kind, is extremely stimulating in its pure form. The women whose stories I got to learn became a symbolic representation of the whole generation for me. Their experiences as young girls living in a totalitarian regime are a universal message on what it was like to live on the edge. It is not only about their personal stories, but potentially about stories of every one of us. The power and beauty of these women kept the world going until now, against all logic… When I familiarised myself with the biographies of the Polish Mothers (Polnische Mame), I delved deep into their personalities and identities, and tried to learn the truth about the nature of humans and the purpose of our existence. I studied beauty but eventually I found myself face to face with crime. My goal was not to let the memories of these women’s intimate experiences sink into oblivion. We have to be aware that they generated the building blocks for the world as we know today. The world whose driving power is now in our hands. It was probably my ominous nature which made me aware that if we let uncomfortable topics fade away, demons of the past will come back and haunt us here and now. If we learn from the stories I tell through my project, we will be closer to understanding the miracle of life. Sometimes one day, an hour or even a few minutes can determine our existence… I decided to use the medium of photography because, as Barthes said, the eidos of photography is “this is past”. Photos are inanimate myths and rituals aimed at bringing back memories. Combined with text they evoke the stories of Polnische Mame and make them vivid. This is a feminist exhibition and it shows the extraordinary power of women. It serves as a tribute to their generation, unfortunately, there are less and less members of it, so our awareness of their fate is fading. I wish we lived in better times.

Translated by Joanna Pietrak

Proof read by Maggie Kuzan

Edited by Monika Tramś

Paweł Kowalewski, “Blanka” from series “Strength and Beauty”, offset printing on bidond, 180 x 140 cm.

Paweł Kowalewski, “Zofia” from series “Strength and Beauty”, offset printing on bidond, 180 x 140 cm.