Demon’s Brain is an installation conceived as a result of Polska receiving the prestigious Preis der Nationalgalerie award in autumn 2017. This multi-channel video installation was specially created for the Hamburger Bahnhof – Museum für Gegenwart – Berlin and located on the ground floor of the Historical Hall. As the starting point of her work, Polska takes a correspondence from the 15th century between Mikolaj Serafin (who governed the Polish salt mines from 1434 to 1459) and his workers and debtors. The artist reached back to the history of 15th century Poland and a casus of the salt mines, which was leased to Serafin by King Władysław III (1424–1444) and functioned as an early form of capitalist entity within the feudal system, and alluded to today’s current affairs concerning consumption, environmental destruction and data capital.

Agnieszka Polska, The Demon’s Brain, 2018, Multichannel video installation, film still, © Agnieszka Polska, Courtesy ŻAK | BRANICKA, Berlin and OVERDUIN & CO., LA.

Agnieszka Polska, The Demon’s Brain, 2018, Multichannel video installation, film still, © Agnieszka Polska, Courtesy ŻAK | BRANICKA, Berlin and OVERDUIN & CO., LA.

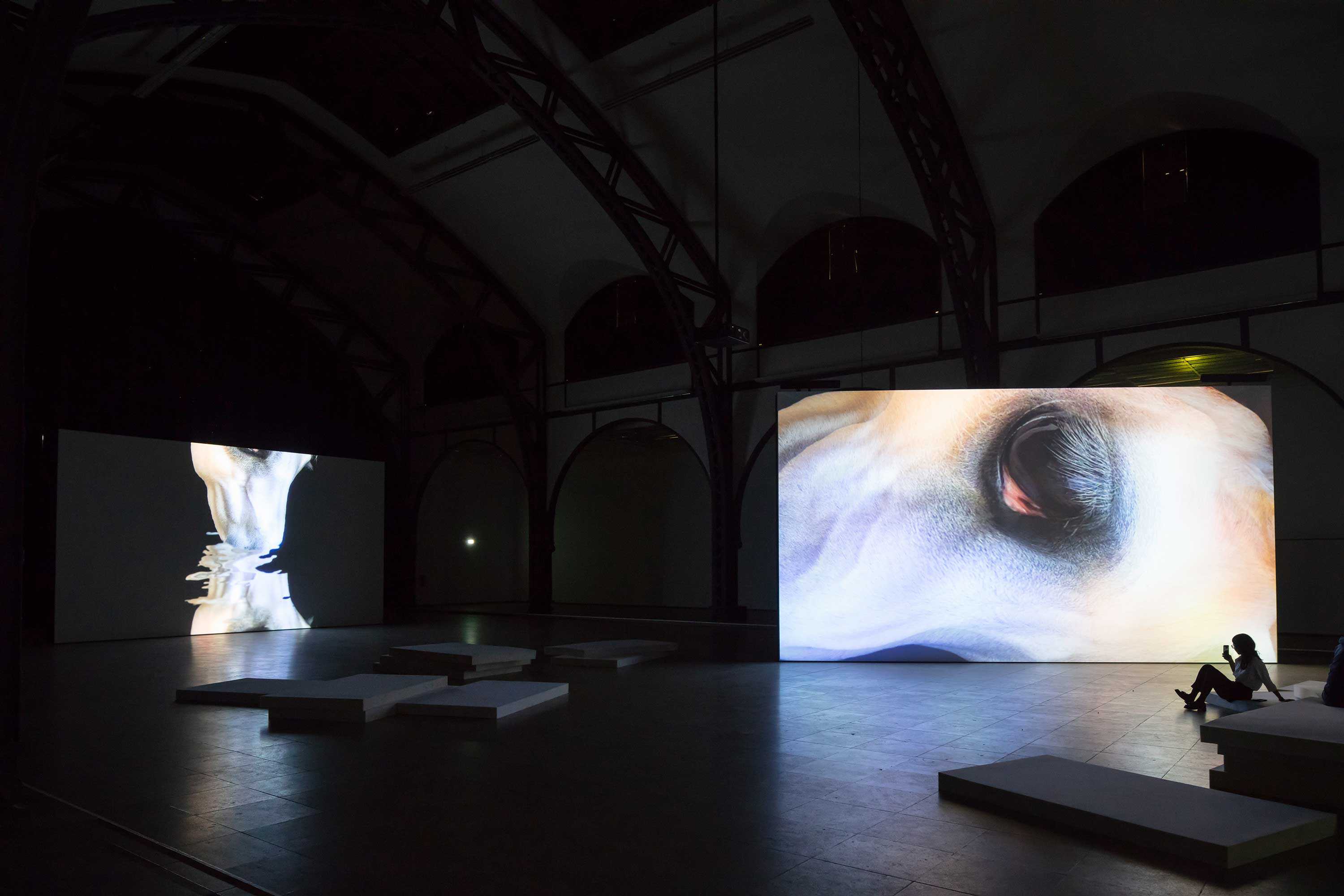

The installation consists of four large-format projections and a wall of texts. The first two films tell the fictional story of a young messenger, who has to deliver a letter. On the journey, he loses his horse and at night he meets a peculiar phantom – a demon, which convinces him to burn this letter. The other two films are animations of a white horse and a black raven and a film about a never-ending wander through a mine tunnel.

The story of Serafin would not be particularly interesting if not the fact that in the 15th-century feudal system in Poland, all salt mines belonged to royals. Serafin however, managed to lease them from the king and created a form of modern enterprise. Their functioning was based on paid labour and work schedules. Serafin also managed to control the market along with his network of creditors and debtors. The clash of two systems: a feudal and a capitalist, seems to be not only interesting in the context of the past but also in the future of social development.

Agnieszka Polska, The Demon’s Brain, 2018, Multichannel video installation, film still, © Agnieszka Polska, Courtesy ŻAK | BRANICKA, Berlin and OVERDUIN & CO., LA

In the first two films, the strong narrative plot combines elements of the past and the future in such a way that sometimes it is difficult to distinguish when the story takes place. The story seems to be staged in the past, but the demon itself comes from another dimension. It has features typical for a demon: it is black with eyes of two different colours, its form is virtual and very graphic. It is not known where exactly it came from; it only says that from a miraculous place. Does it represent our modern times? Or maybe it goes beyond that – the future? Maybe it is a robot or a form of artificial intelligence? An interesting aspect to consider is why the demon managed to convince the young messenger to burn down the letter. What impact does this decision have on him and the whole story? Could we interpret it in a historical way, as if in the past our future was already present and had influenced it?

The feeling of the past meeting the future can also be seen in the landscape. When the messenger rides through the woods, scenes from our modern times appear, and suddenly the scene takes place in the middle of deforestation.

Agnieszka Polska, The Demon’s Brain, 2018, Multichannel video installation, film still, © Agnieszka Polska, Courtesy ŻAK | BRANICKA, Berlin and OVERDUIN & CO., LA

Using these effects and shifts from different time dimensions gives the impression of parallel worlds, in which moments from the past and the future happen at once. Often the artist says that the main idea of the project was to show the degradation of nature and of the whole natural system, which did not start yesterday but is a process that began a long time ago and continues to this day.

This idea can also be deduced from fragments taken from the correspondence of Michał Serafin, which are presented in conjunction with the exhibition. In these letters, he describes problems and actions connected with supervising the salt mines, which could also be typical struggles in the management of a company today.

But the other aspect, which I think is even more interesting, is the mineral, the salt itself. In 15th century Europe, salt was a precious currency, giving power to those who possess it. Right now, this mineral is not of much value and has no strong economic meaning. Other minerals or metals have replaced it, for example, those used in our smartphones or computers.

Agnieszka Polska, The Demon’s Brain, 2018, Multichannel video installation, film still, © Agnieszka Polska, Courtesy ŻAK | BRANICKA, Berlin and OVERDUIN & CO., LA

Even though the object of speculation changes and depends on the economic needs of the times, no matter if it is salt, coal or cobalt, mining was and still is connected with extensive and unsustainable exploration and a heavy toll exacted on human and natural resources. The system created by Michał Serafin was not an exception but simply part of the system, which has existed over time and equate the past with the future.

Let’s talk about art but not about us

In November 2017, shortly after the opening of the exhibition at the Hamburger Bahnhof, four nominees (among them Agnieszka Polska) published an open letter, in which they expressed their criticism at the prize itself. Firstly they pointed out that they felt like the prize ceremony was all about the sponsors, who supported it and not about the art. They also asked about the sense of competition as a form of gratification. At the end of the letter, they expressed their disappointment at the financial conditions of the prize. Although the prize includes no financial reward, the artists could have received some financial support for preparing the show as well as for participating in a series of obligatory events planned by the organisers.

Agniezska Polska: The Demon’s Brain, Ausstellungsansicht Hamburger Bahnhof – Museum für Gegenwart – Berlin 2018, © Staatliche Museen zu Berlin, Nationalgalerie / Thomas Bruns

Last but not least the artists related to the situation around them: being four female artists from non-Western countries became the most important issue, often emphasised to promote the show and the prize itself. The discussion focused on talking about their background and the fact that they are all women, which again pushed the most important aspect aside: the discussion about the art that they were making. It seemed that as a whole, art played a secondary role and the main focus was put on sponsors and upholding the image of a progressive and gender-equal art scene in Berlin, which is not entirely true.

The issues brought up by the four artists are not exclusive to Berlin but are universal problems. The question of the value of artistic labour and the precarity of working in the arts has become more and more visible and is an urgent problem. This is particularly so after the publication of the survey called Studio III, which reveals how miserable the financial present and future situation of Berlin artists is (the results of the survey are also available in English at www.ifse.de) — in most cases, being a Berlin artist doesn’t necessarily pay off. Is the form of an exhibition the best of possible reward for an artistic work? In the end, does the institution help the artist or does the artist help the institution? Who needs whom and for what? Could we always see it as a win-win situation?

Agniezska Polska: The Demon’s Brain Ausstellungsansicht Hamburger Bahnhof – Museum für Gegenwart – Berlin 2018, © Staatliche Museen zu Berlin, Nationalgalerie / Thomas Bruns

Agniezska Polska: The Demon’s Brain

Ausstellungsansicht Hamburger Bahnhof – Museum für Gegenwart – Berlin 2018, © Staatliche Museen zu Berlin, Nationalgalerie / Thomas Bruns

Talking about winning, the four nominees also mentioned the matter of competition. In times of constant thinking about sustainability, also in the art world, is the model of “the winner takes it all“ not an inadequate one? Does this division between an individual that wins and the rest that loses still make sense? Or should we rethink ways of supporting art and see it as a network of long term support, and not a one-time goal based on inequality?

Unfortunately, all the issues addressed in the letter are still left open. The letter itself didn’t lead to any brighter discussion on the Berlin art scene. But if it at least has some impact on the prize itself, that will be possible to verify. The shortlist of the four candidates nominated for the 10th edition of the prize should be announced any time soon.

Agnieszka Polska: The Demon’s Brain

27.09.2018 to 03.03.2019

Hamburger Bahnhof – Museum für Gegenwart – Berlin