Netta Laufer is an Israeli-born artist raised in both Jerusalem and New York. She is interested in the power dynamics between humans and nature and the impact of the postcolonial human-made borders on the funa and flora. In her work, she uses materials from CCTV cameras, maps and technical drawings.

Tom Swoboda is a Polish artist and a co-founder and manager of the Szara Gallery in Cieszyn where he currently works and lives. His art deals with the issues of spirituality and memory and their impact on society. Recently, he has been focusing on “Animal Space”, a project centered around the subject of artificial human-made spaces designed for animals.

You can view their work at the “Territory” exhibition held at the Wrocław Contemporary Museum until 8th March 2021. The exhibition, curated by Agata Ciastoń, touches on the subject of human and animal territories and how they coexist in the Anthropocene. Netta Laufer approaches the topic from the Israeli-Palestinian perspective while Tom focuses on the image of a zoo.

On the left: Netta Laufer, 35 cm, 2017–2020, photographs, exhibition copies. In the background: Tom Swoboda, Animal Space – The skin of an elephant, metal object, photo print of an elephant skin. Photo by Małgorzata Kujda, © Wrocław Contemporary Museum, 2020.

Tom Swoboda, Animal Space, 2020, photographs. Photo by Małgorzata Kujda, © Wrocław Contemporary Museum, 2020.

Netta Laufer, 25 FT, 2016, photography, video. Photo by Małgorzata Kujda, © Wrocław Contemporary Museum, 2020.

Aleksandra Mainka-Pawłowska: What do Netta Laufer and Tom Swoboda have in common? Is there a common denominator between them?

Agata Ciastoń: To answer this question, I have to mention where the idea for the exhibition came from, and what ultimately did not become part of it. A few years ago, when I met Netta, I became very interested in her works from the “Cells” series. The artworks are photographs referring to artificial environments created for animals in zoos – there are no inhabitants in them, instead they show spaces arranged in a way we, humans, understand as “proper”. Shortly after, I came across Tom’s photographs from the “Animal Space” series which explore the same subject, but are more documental and austere. That’s when I thought the zoo could become the subject of their joint exhibition and that’s what the three of us believed for quite a while. That was the strong “common denominator” you are asking about. However, when Tom and Netta got acquainted, and as I started listening to their conversations and having, sometimes very emotional, discussions with them, I realised what made them different was much more interesting. That’s why, in the end, Netta’s other works – “25 ft”, “35 cm” and “365” – and not “Cells” are part of the exhibition. They form a triptych of sorts, as they deal with the same topic.

In the meantime, Tom’s works from the “Animal Space” series have evolved strongly. In a way, this “common denominator” has changed a lot and became less obvious. Although Tom remained faithful to the subject of artificially created zoo spaces, the emphasis has been shifted to exploring the borders between “them” and us, the need to cross them, to get closer, to decide how far we want to go. In my opinion, his works are also about the power of human gaze and how strongly it determines our relations with animals, about how difficult it is to move beyond that gaze. Netta’s work also touches on the subject of the gaze and how it’s imposed on animal territories. In her case, the controlling power of the gaze takes on a more literal dimension since in her photographs she uses materials obtained from Israeli CCTV cameras located along the Israeli West Bank barrier. This security system also entangles animals, affects their way of life, divides their natural territories and makes them become involuntary “characters” of Netta’s works, but also participants in our (human) conflicts which they also metaphorically represent. However, there are also small details that make the dialogue between the artists take place on several levels. One of them is concrete, the main building material of the Israeli wall, which is also a key element of the objects created by Tom. The Wrocław Contemporary Museum’s headquarters are also built from it. And so, concrete ceases to be a neutral material – we begin to perceive it as part of a system of force and violence.

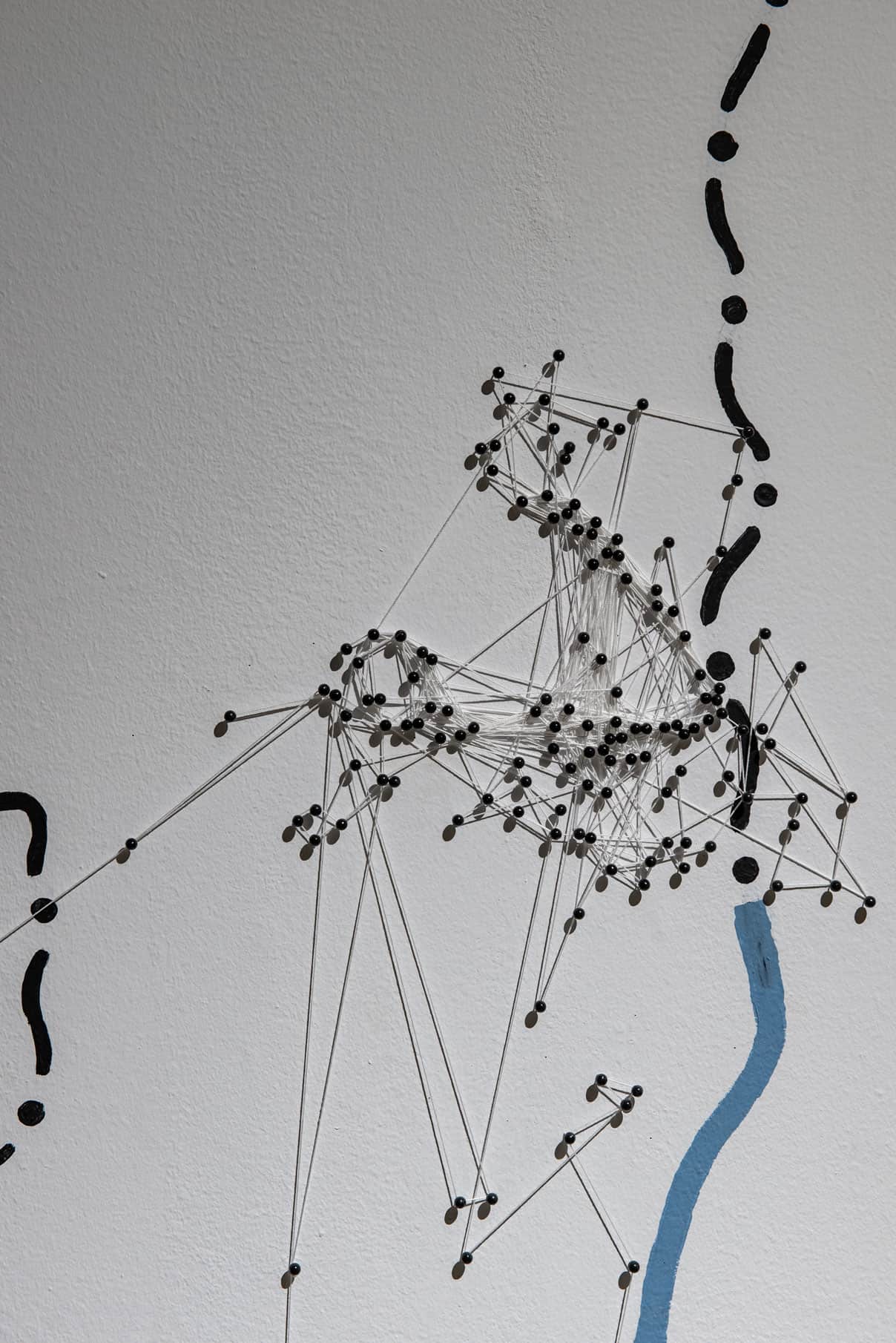

Netta Laufer, 365, 2020, installation. Photo by Małgorzata Kujda, © Wrocław Contemporary Museum, 2020.

AMP: How do Netta and Tom interpret the notion of territory and show it in their works?

AC: Before I answer, I would like to stress the fact that the title “Territory”, with all its powerful meaning, was not a theme imposed on the artists to create or select works. Their works are therefore not an illustration or even an interpretation of the term. For a long time, we worked with a working title that did not suit us at all, but we could not find a better one. The whole idea for the exhibition was created between the three of us, in conversations, exchanges of opinions and ideas. This is how the word “territory” came to us. It seemed interesting because of its sound and typographic arrangement. We agreed that it resembles a cage, it’s strong, imposing and sounds very similar in Polish and English (the title had to be bilingual) so it probably evokes similar feelings. At the same time, it’s the very essence of the themes of the exhibition as it describes both animal domains and national borders, both of which invisibly limit how beings move and behave within their limits. I’d like to refer to a specific part of the exhibition, an important aspect of it in which one can clearly see how territory can be “interpreted”. For the purposes of the exhibition at Wrocław Contemporary Museum, Netta has expanded on her artwork “365”. It’s a depiction of the movement of a hyena that—as the result of an intervention of the Israeli military forces (IDF)—moved around the Palestinian territory where it was tortured. The hyena was cured and a transmitter was implanted to track her. The artist received data from it and created an installation based on the route—on a schematic fragment of a map painted on a wall, the animal’s path is marked with a string and pins. The hyena moved freely between Israel and the West Bank, it also made trips to Jordan. Please, bear in mind we’re talking about an area of the world where the way people move is strictly limited and dependent on many factors. Netta could not go to the places the hyena had visited – it’s harder for her to cross the border to the Palestinian territories and it’s almost impossible for the Palestinians to cross to the Israeli side. It is also an area where the range of equipment using the Internet is blocked by the military, so the record is not complete. You can see the hyena travelled through an absurd entanglement of boundaries without being aware of them and which, with the help of paint, string and pins, now materialise on the wall of the museum. Next to Netta’s installation, we placed Tom’s “Ring”—a metal circle surrounding a concrete pillar which is part of the bunker’s construction. The work clearly refers in its form to fences surrounding animal enclosures, but in this case it’s a barrier that doesn’t provide any protection making it seem almost absurd. Both works refer to movement and its limitations.

AMP: Does the choice of photography as a medium change the way we see Netta’s and Tom’s artworks?

A.C.: I think photography is not a “medium” here – it’s not there to show or reveal something to us. On the contrary, it highlights the limitations of the image itself. Netta’s photographs in “25 ft”, which are CCTV camera footage, are so blurred and hazy that our eyes are hardly able to see animal shapes and landscape elements. And yet, at the same time, the chosen perspective connects our eyes with the eye of the camera and makes us feel uncomfortable.

In turn, Tom’s use of the camera is, in my opinion, subversive, as these places are meant to be photographed, and he does it in an almost perverse way. He doesn’t follow marked paths, he notices what should remain hidden. However, it doesn’t help us approach the animals which reveals our helplessness as no matter how long and hard we look at the surface of the glass (the animal cage, or the frame of the photograph itself), what we see is still nothing else but our own reflection.

Netta Laufer, 25 FT, 2016, photographs. Photo by Małgorzata Kujda, © Wrocław Contemporary Museum, 2020.

AMP: Tom, could you tell us what inspired you to create the “Animal Space” project?

Tom Swoboda: There are many possible answers to this question. It was probably a combination of events, projects, places that could have had a major impact on me a few years ago. I believe two aspects were certainly linked to the creation of the Animal Space project. Firstly – animal theory. For many years, I have been working on a project centred around drawings I made with my body in the mountains and forests. They are routes I travel alone without any time constraint or imposed aesthetics. What matters is the strength of muscles, mind and landscape. The created line (the route saved in .gpx format) often crosses areas inhabited by wild animals, their territories. I have learnt to be human, I would like to become an animal.

The second aspect refers to the architecture itself which is the strongest (the most permanent) description of human domination, plundering of territory. In recent years, I have had an amazing number of architectural dreams. They were descriptions of non-existent buildings and places. It was a matter of time before I found these combined images embodied in zoos. The first visits were a powerful experience, intertwining anger, sadness and smell into one foreign sensation. The incompetent recreation of native places in cages and aviaries became the main focus of the project.

“Animal Space” is a long-term project documenting (mainly through photography) the living space of animals in zoos. Over time, it has become kind of an archive of changing spaces, cages, paddocks, a record of a great misunderstanding of the nature of different animal species and their native environment. The image itself is recorded in a rigorous way. Reflections of cage lighting fall into the frame, the perspective is shaken and the colours saturated. All depends on the situation. This further highlights the absurdity of the design of animal interiors—a mere simulation of nature.

In 2018, a wild boar roamed into a church in Ruda Śląska (Upper Silesia, Poland), destroying two vases and a statue of Jesus. The congregation set up barricades from benches and banished the animal from the temple. A funny situation, but for me it carries more meaning than just news in a newspaper. It’s an example of the intersection of territories, of a balance of power. I see the story of the wild boar as symbolic. The animal destroyed God.

AMP: Can you explain why animals are almost absent in your photographs?

TS: While carrying out the project, which is partly based on a documentary approach, I set the parameters for lighting, framing and photographic equipment—I didn’t want to take pictures of empty cages alone. On the other hand, I wasn’t interested in “animals’ life scenes” in captivity. From the very beginning, I was interested in this invisible conventional (yet delineated) boundary that’s status quo. In a way, making the animal absent came naturally when I was spending time in those places. I dare say the strength of a cage is so powerful that it pushes the animal somewhere to the background, gets rid of it. It is a situation of a spectacle where in front of a glass pane or a grating—outside, a viewer appears craving to watch, sometimes even be on the other side. The performance ends cyclically with the death of the animal. I began to understand this absence by documenting the interiors of cages.

Tom Swoboda, Animal Space, 2020, photographs. Photo by Małgorzata Kujda, © Wrocław Contemporary Museum, 2020.

AMP: What kind of narrative do zoos represent? What position do they put the man and the animal in?

TS: Again, I don’t have a clear answer because it’s a conglomeration of observations, texts and thoughts that circulate around those places. We can start, of course, with the most popular narratives, concerning crowds participating in zoo tours, i.e. pure human desire to peep, curiosity, education. On the other hand, in the era of the Anthropocene and the increasing human interference in the natural environment, there are a few examples of seeing zoos as time capsules, potential places where animal species are being restored.

A tame, caged animal, in particular those species that are dangerous to men, becomes real or has a symbolic use. Be it for riding it, eating it, or taking a picture with it. Men want to possess and control them. The architecture of zoos favours this – we’re not afraid of the animal anymore. I think the very problem of control over animals isn’t a contemporary one, but is much more rooted in the Judeo-Christian culture in which God gives man full control over these ‘incomprehensible creatures’. Even if God’s aim was to protect them, he unfortunately did them a disservice.

AMP: Netta, could you tell us more about your artistic process? How do you create your photographs?

Netta Laufer: My main motivation is to explore the questions about our relationship with nature. Through various collaborations with authorities either from the government, or military fields, I’m able to obtain and create the images I’m interested in. Each collaboration yields a unique view, depending on the specific function of the authority, and the technical equipment (i.e. CCTV cameras, motion tracking cameras, maps and technical drawings). Since my images put me in the role of a distant observer, I occasionally visit the areas that I investigate (West Bank), where I can further learn about the environment and meet people that I can collaborate with. Through a comprehensive editing and sorting process of the appropriated footage, I’m able to fully control its reservoir of content.

AMP: How does the political situation in Israel affect your art? Do you think your art would look different if you lived somewhere else?

NL: My work deals with the effects of Post-Colonialism and the Anthropocene on the dynamics between humans and nature, through political power systems. As an Israeli, I’m naturally influenced and exposed to political issues which are closer to me physically and consciously. Although living elsewhere in the world (nationality-wise), would likely result in exposure to different expressions of this relationship, they will still evoke the same tension and questions.

Tom Swoboda, Animal Space – Ring, 2020, installation. Tom Swoboda, Animal Space, 2020, photography. Photo by Małgorzata Kujda, © Wrocław Contemporary Museum, 2020.

AMP: In your photographs, people can be seen as oppressors. Does human presence always affect the world of fauna and flora in a negative way? Or is it possible for people to coexist with animals?

NL: Personally, I believe that in general, as long as we live in a capitalistic culture, coexistence of humans and animals will become more and more difficult. As an artist, I don’t allow myself to think in terms of negative and positive. I am more interested in the questions and terms that create the tension. It is the observation of the questions themselves, that triggers awareness. The appearance of, and the encounter with an animal, under the context of a border patrol and surveillance, suspends the totality and the immediacy of a certain response. The presence of animals in the image awakens viewers to an understanding of being human (as opposed to the animal); and consciousness and the acknowledgement of moral responsibilities that define good and bad. The appearance of animals throws the border, its function and what it stands for, into question for the soldier who surveys it and for the viewer in front of the work. Thus it is doubt that threatens the borders’ integrity more than anything else.

You can view “Territory” at the Wrocław Contemporary Museum

from 4th December 2020 to 8th March 2021.

Tom Swoboda, Animal Space, 2020, photography, light box. Photo by Małgorzata Kujda, © Wrocław Contemporary Museum, 2020.