Helena Postawka-Lech: Yane, your artistic work is often about creating something meaningful from the immaterial — archives, history, memories. The narration of your works is built upon this base, which also allows you to reinterpret the history of the institutions you cooperate with.

Yane Calovski, “Something laid over something else”, the exhibition: “All Mounds Can Be Seen From My Window”, Bunkier Sztuki Contemporary Art Gallery, Kraków, 2016, photo courtesy the gallery

Yane Calovski: My work is mostly based on my work with information, which often does not get written down anywhere, but rather constitutes a part of people’s memories, and their oral history. This is why my work on individual projects is a truly spontaneous process. I always try to establish a close relationship between myself and a place or an institution while I am working. Conversation is a crucial thing, so I make that my starting point. It can be quite unpredictable at times and can develop in a direction you never would have expected. Sometimes these conversations are focused on details, some times they are directed towards the underlying general principles of a given institution, which invited me to work for them. However, I usually don’t feel any pressure to work on a single defined topic. I find an aspect which is particularly interesting to me or which would present an exciting challenge independently. I recently worked with Bunkier Sztuki Contemporary Art Gallery in Kraków, which is a really interesting example of late modernism. It was designed by a woman, which seems important, because what we see there is brutalist architecture. I have seen a lot of such architecture in Skopje. Bunkier seemed really interesting to me as a whole or a complete structure. My initial conversation with their team of curators of the exhibition was about specific changes to the building, which had been occurring throughout the years. Many of those changes have not been documented in any way and are just present in people’s memories. We managed to isolate the building, in a sense, during our conversations so that it became an independent object. This was an important experience for me. I wanted to propose a work composed of certain elements which, on one hand, would be sculpture-like, but on the other, it would be possible to find another logical function for them and use them within that space appropriately. That is why I used hand made synthetic rubber which I produce myself using a certain chemical formula. Thanks to this formula, the material hardens as time passes and is subject to a vulcanization process, in other words, it has its own performative dynamics which slowly manifests itself during the time when the exhibition is open. This work will never have a fully established form — it is a crucial detail which cannot be seen with the naked eye, but is essential for the development of the work’s narration. This way, hand made synthetic rubber becomes a kind of skin which is ready for its functions and for being interpreted. By definition, it is a material which is associated with amnesia; it does not have its own memory. It is also about rubbing things out, erasing meanings and content. At the same time, it absorbs dirt and different stains. That is how my work will embark on its own, historical process of remembering touch and content. I also wanted to create a common interface between this hand made synthetic rubber, the floor and the walls. I used stainless steel for this purpose. This material is characteristic of modern architecture, it is shiny and becomes meaningful only when it starts to reflect something or is transformed in some way. Before it is personalised, it means nothing. The process of personalisation of this work is something which my audience themselves are experiencing to a certain extent. I like this work as a whole, but I also like its performativity and the fact that it can be changed in some way by mere touch.

While working on this project I also wanted to create a kind of document, something which could be stored in archives. That is why I created a series of drawings which constitute an integral part of the work and which I made on archival paper. While I worked on this project I received an old ream of paper from the institution’s archives, probably dating back to the 70s. The frame is really minimalist on this paper and it is broken, so that it does not restrain the composition in any way. It is just the opposite — the composition remains open. Such composition was born after I analysed the open form concept developed by Oskar Hansen. In this way I could easily tell people about the various possibilities of illustrating this theory within the context of an interior of this particular institution i.e. an environment which constantly evolves and changes.

Yane Calovski, “Something laid over something else”, the exhibition: “All Mounds Can Be Seen From My Window”, Bunkier Sztuki Contemporary Art Gallery, Kraków, 2016, photo courtesy the gallery

HPL: How and when did you first learn about Oskar Hansen’s works?

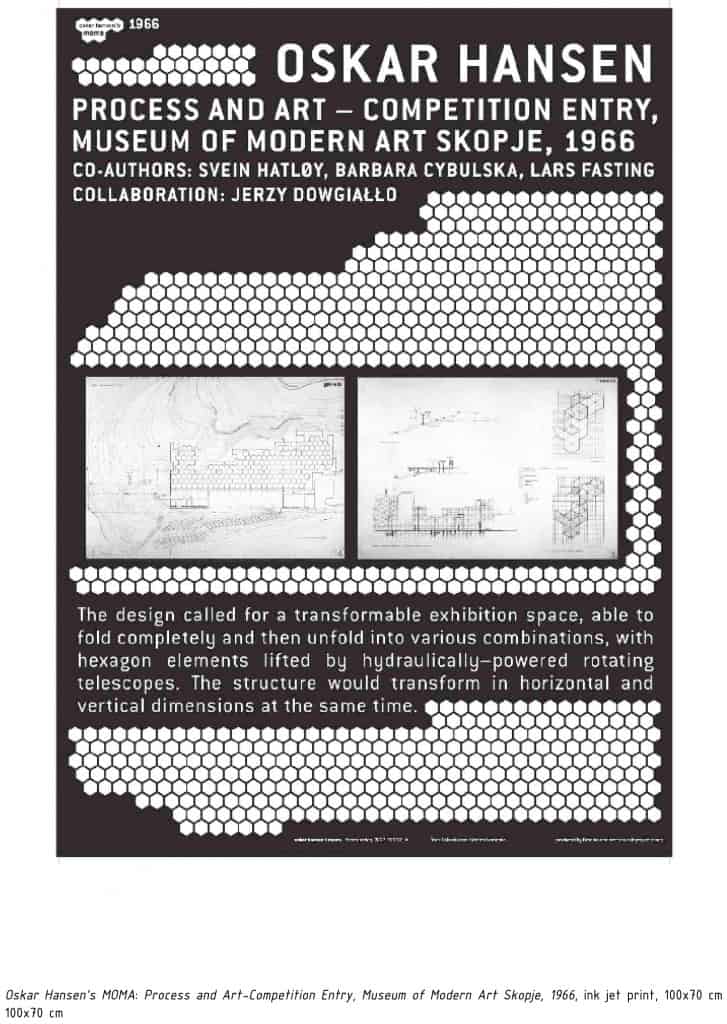

YC: I got to know Hansen when, together with Hristina Ivanowska, I prepared the work based on the non-realized design of the Museum of Contemporary Art in Skopje. After the 1963 earthquake, when a large part of the city was completely destroyed, different nations showed their solidarity by preparing designs of new buildings. The design of a new building for the museum was a gift from the Poles, and there was a contest in which different Polish architects had participated. The contest had a closed and national character. The winning design which was planned for implementation was prepared by a team called the Tygrysy (Tigers) (Wacław Kłyszewski, Jerzy Mokrzyński and Eugeniusz Wierzbicki, who were familiar to the Polish nation thanks to their designs of the railway station in Katowice, and the Philharmonic Hall in Rzeszów — note by HPL). The fact of Hansen participating in this contest has never been widely known. Therefore, quoting this fact is, again, possible thanks to oral history. We had some knowledge about Tygrysy, but it was not very detailed. We also do not know anything about all the other designs submitted for this competition. It was Sebastian Cichocki who directed our interest towards Hansen’s design. We developed this concept and, crucially, we cooperated with its author. We invited Sebastian to Skopje for an artistic residency programme in 2005. He was the first participant of our programme entitled: “Press to Exit Project Space” which we initiated in order to attract international community to Macedonia and see what interesting and appealing international artists and curators we were able to find here. Sebastian came with museum building designs prepared by Hansen. We were really lucky because these were the final years when Hansen was still alive. He knew what we were working on and gave us really beautiful copies of plans and elevations of this building and a copy of a monograph he has been then working on. We worked on our project for about a year and during this very year Hansen died. Our success would not have been possible without Sebastian who is an excellent curator and our friend. He has extensive knowledge about the history of art, probably thanks to his education which also includes the field of sociology.

‘Oskar Hansen’s MOMA’, Yane Calovski and Hrsitina Ivanosk, courtesy the artists

HPL: The story of the creation of the Museum of Contemporary Art in Skopje is truly exceptional — a ruined city, contributions from other countries and, all of a sudden, the fascinating, quite unrealistic design by Hansen. What were your first impressions and what made you and Hristina develop your own work on the basis of what Hansen created?

YC: At the beginning, we were shocked that we did not know anything about it. Then we studied Hansen’s design and were impressed with its excellence. This design is incredible as a proposal but I don’t know if it’s credible as a real building. It is composed of galleries lifted on hydraulic ramps. The whole building is located on a hill, so that it faces the city. The city inhabitants would have the possibility to observe the building and would know that the galleries lifted above are a sign that something meaningful happened in art and the museum is then worth a visit. The building would play a part of an indicator or a signpost. The rest of the building was supposed to be hidden underground, inside the hill and function as a laboratory. This was a truly avant-garde idea. Numerous modern institutions which define themselves as research laboratories function on the basis of avant-garde principles. I think that Krakow’s Bunkier is one of them.

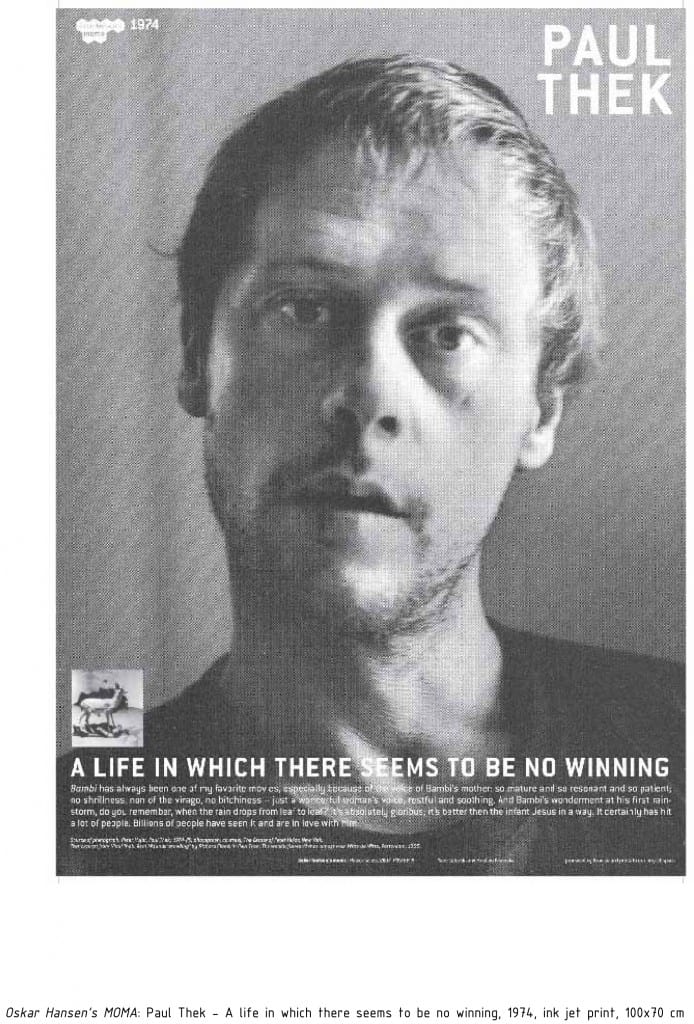

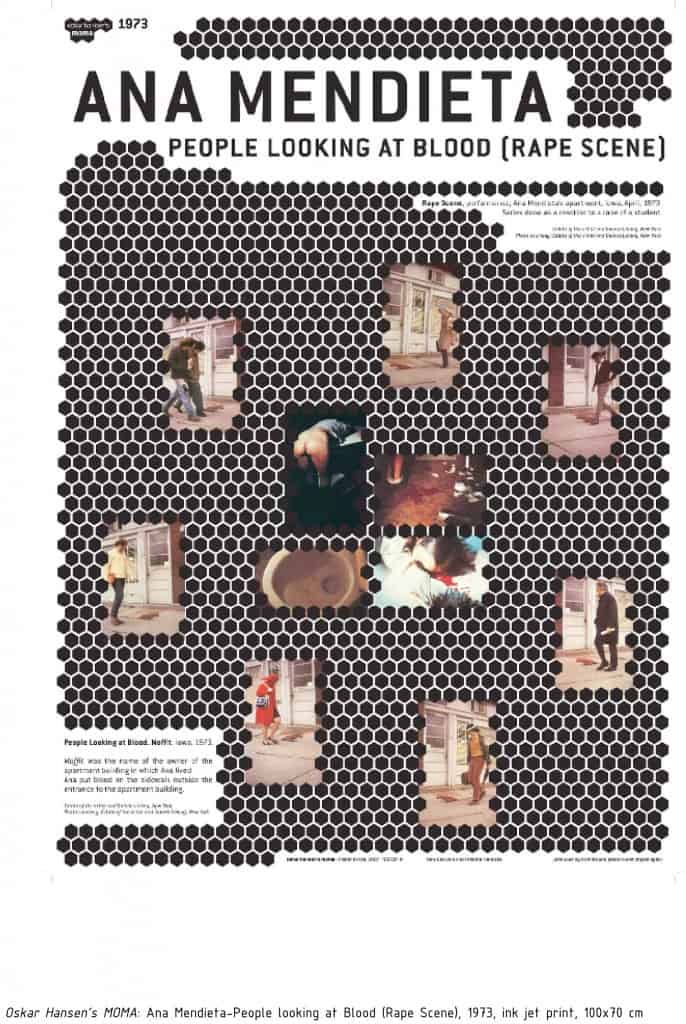

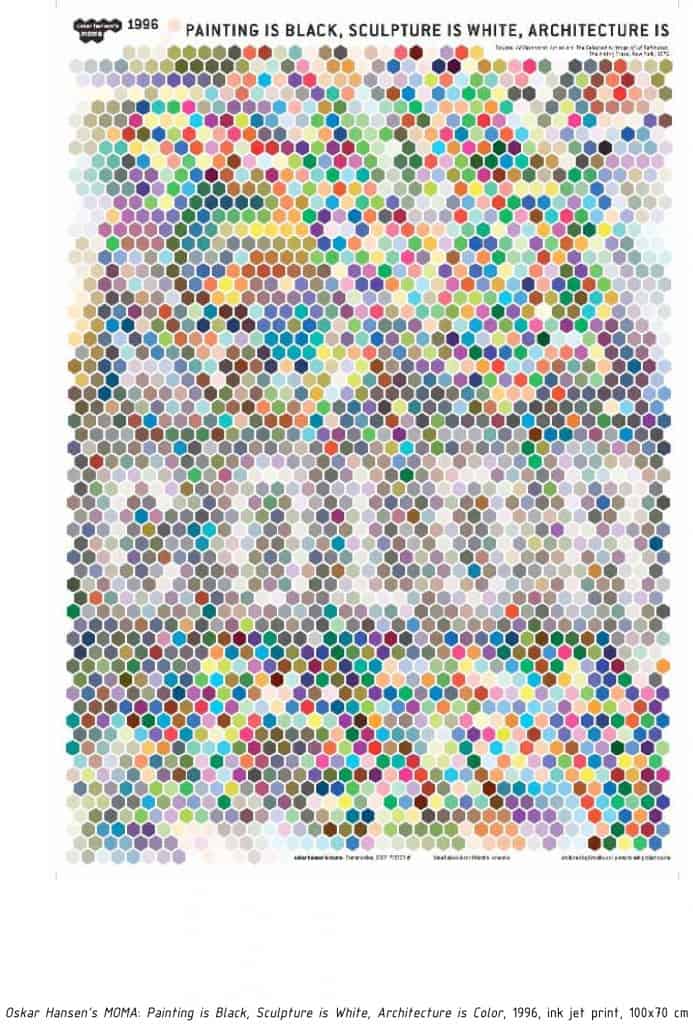

What is more, we were fascinated by Hansen’s understanding of the potential shown by the museum designed by him to be built in Macedonia. The “far far away” museum has not been finally built but was designed, which proves that its creation, location, etc. were actually considered. What seemed really interesting to us was the possibility of considering this project not as a proposed building design but rather as an invitation to create proposals of a programme. This was what we tried to create — a draft of a programme for a museum not yet built but possible to build. We created a series of 12 posters with the first one containing a quotation of Ad Reinhardt. The idea we included in our poster was first expressed by him in 1963, before the Museum design was created. So our first poster was dedicated to the beginnings of discussions about the museum, which took place at that time. The quotation we used comes from a series of Reinhardt’s letters which are considered a protest — letters are supposed to be understood as a protest or an opinion of an artist who is part of the system but retains his critical opinion of it. In subsequent posters we made references to artists and their letters, who and which are important for me and Hristina for various reasons (e.g. Paul Thek, Mladen Stilinovic, Andrzej Szewczyk, Ana Mendieta). We tried to analyse and reinterpret them through design and a system of visual points of reference.

Yane Calovski and Hrsitina Ivanosk, ‘Oskar Hansen’s MOMA: Paul Thek – A life in which there seems to be no winning’, 1974, ink jet print, 100×70 cm

Yane Calovski and Hrsitina Ivanosk, ‘Oskar Hansen’s MOMA: Ana Mendieta-People looking at Blood (Rape Scene)’, 1973, ink jet print, 100×70 cm

The result of our efforts was a surprisingly illustrative work. Everything we thought about, read about, what we understood and collected — this whole subjective curatorial process was concentrated around certain knowledge, and it resulted in the inclusion of things mentioned above in these 12 posters and was aimed to test their effect. Surprisingly, it all seems to be working. We thought about the programme for an unreal museum and what it would look like if it was based on real events, works of art, figures — everything which existed and took place in reality and in real time. We thought about it in the context of Eastern Europe and the challenges of dominance paradigm in reference to Western culture; we were considering whether we were a part of this culture, or whether we were actually outside of it, and how we function within it.

HPL: The “orphan of culture” figure is also present in your works — it even appears in the title of one of your exhibitions “Sieroty, Legendy i Bohaterowie Sztuki” (Orphans of Culture, Legends and Heroes) presented in Galeria Kronika in Bytom from 26 May to 14 July 2007. Why is this figure so important for you and your artistic activity?

YC: It is interesting that you should ask me that. Orphan is a question about the way in which we work with the past, and also when it comes to the figure of a hero or a legend.

I used to think that we practice with full awareness, knowing that we have history behind us and that we know where we come from, either consciously or unconsciously. However, we participate in the present and I have the impression that we are left here on our own. Of course, there is history and our future, but we are completely alone in the given moment. This, at least, is my experience. Our ancestors are no longer alive — they were killed, rubbed out from our memories, either by us or without our participation. On the one hand, we feel the need to connect with history, but, simultaneously, we need to be on our own and try to understand everything once again, even if we analyse some old idea which is not original. This is a really interesting thing — the way in which we contextualize history, how we deal with legends, heroes, orphans, things which were present in the past and things we still experience today.

Let’s go back to the notion of originality for a while, as it is genuinely problematic for me. Every work has a certain atmosphere or sensation telling us that all of it was already created as a starting point. We have the feeling that many domains had already been worked with — conversations or thoughts, knowledge not fully defined, but which we gained somewhere along the way and in the course of our artistic activity. That is when we start asking ourselves a question — what to do with this dispersed knowledge. It is not important whether our artistic gesture would be big or small, it is not about the size. It is about this gesture being understandable. This is what I am struggling with — creating works which would generate a new kind of tension between history and the present times but could also be prominent in the future. However, I cannot be sure about the latter, since it does not depend on me.

HPL: What did your work on this project, the work with Hansen’s creation, bring to you?

YC: My first thought was that — such a proposal, which still remains unknown and not present in the consciousness of the general public, would mean a lost opportunity. We thought — what an interesting, sensational, and wasted opportunity! That was our initial reaction. Now, as researchers, we look at it in a different way. In some ways, we fell in love with this project. It boosts your imagination and, suddenly, you realize that a very clear and honest arrangement has been proposed, one in which a museum remains underground and needs to find a reason to appear above ground. In other words, it is not always open or democratic. This way of operation is similar to a scientific laboratory, where prominent results of research are published but it is the researcher who decides when to do it, when the work is ready and the proper time comes for them to do it with full respect for the audience. For us, this is an excellent quality whose potential has not been realized so far.

Interviewed by Helena Postawka-Lech

Yane Calovski and Hrsitina Ivanosk, ‘Oskar Hansen’s MOMA: Andrzej Szewczyk-Paintings from Chlopy’, 2008, ink jet print, 100×70 cm

Yane Calovski and Hrsitina Ivanosk ‘Oskar Hansen’s MOMA: Only a bad Artist thinks he has a good Idea. A good Artist does not need Anything’, 2007,

ink jet print, 100×70 cm

Yane Calovski and Hrsitina Ivanosk, ‘Oskar Hansen’s MOMA: Painting is Black, Sculpture is White, Architecture is Color’, 1996, ink jet print, 100×70 cm

Yane Calovski and Hrsitina Ivanosk ‘Oskar Hansen’s MOMA: Remains of a Summer Day’, 1968, ink jet print, 100×70 cm’, courtesy the artists