Akerman was one of the first film directors who made the switch to visual art. She rose to fame in the 1970s as a feminist avant-garde filmmaker, and midway through the 1990s she discovered the possibilities of the art gallery. In 1995 she created a large spatial installation on 24 monitors based on D’Est, a film she originally made as a documentary. This marked the start of her ‘second career’ within the world of visual art.

As a 25-year-old dropout from film academy, Chantal Akerman acquired instant fame in 1975 with Jeanne Dielman, 23, Quai du Commerce, 1080 Bruxelles. This understated, minimalist portrait of the mundane chores of a Brussels housewife and part-time prostitute was lauded as the standard bearer of feminist avant-garde cinema. In a stripped-down and anti-dramatic style – later referred to as ‘slow cinema’ – Akerman exposed the oppressive routine of a homemaker’s existence and gave a face to the secret life of countless women.

Akerman’s work is characterized by a detached approach to what looks like ‘ordinary life’, but where a profusion of violent events, memories and emotions lurk beneath the surface. Akerman, herself the child of an Auschwitz survivor, is “charging the mundane with significance”.

Chantal Akerman, NOW, 2015. Courtesy Fondation Chantal Akerman and Marian

Goodman Gallery, New York, Paris, London. Photo: Rebecca Fanuele

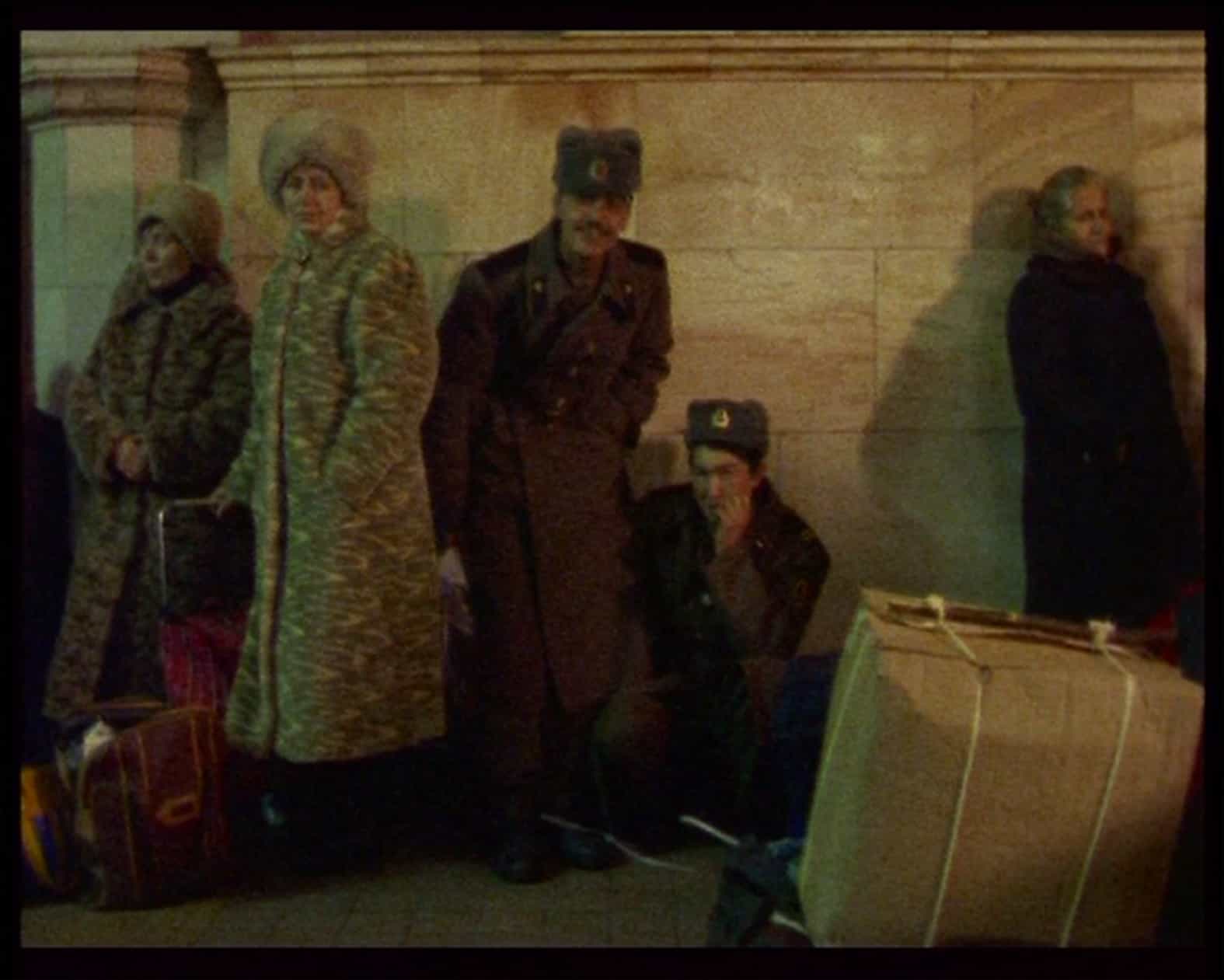

Around 1995 – by then Akerman was the celebrated director of classic films such as News from Home (1977), Toute une nuit (1982) and Nuit et jour (1991) – the filmmaker discovered a world outside movie theatres. Her first video installation was D’Est in 1995, in which she presented hypnotic images on 24 monitors to show how people try to survive behind the Iron Curtain in the countries of the former Eastern Bloc. Her observational images of people and landscapes lack any dialogue or narrative. This installation marked the start of a ‘second career’ within the world of visual art.

Much of Chantal Akerman’s pioneering work testifies to her avant-garde approach to the medium she employs. Features of her distinctive personal style are long shots, frontal camera positioning and wide frames, enabling her to put forward a new interpretation of time and space. Akerman’s works embody history, memories, lives that seem normal but are not. They display an “almost tactile sense of what it is like to observe from a respectful distance, the people and places they record”.

The international art world quickly recognized the remarkable quality of Akerman’s visual work. A series of exhibitions in renowned museums followed, including Walker Art Museum (1995), Jeu de Paume, Paris (1995), Documenta XI, Kassel (2002) and MUKHA, Antwerp (2012). Akerman also took part in the Venice Biennale in 2001 and 2015.

Born in Brussels, Chantal Akerman died in Paris in 2015, one year after the death of her mother, an Auschwitz survivor with whom she had a difficult yet symbiotic relationship.

In the spring of 2020, Eye Filmmuseum in Amsterdam was about to present a major solo exhibition of work by Chantal Akerman. In line with the national policy with regards to COVID-19, the exhibition has been temporarily postponed.

Chantal Akerman, “Dest au bord de la Fiction”, 1995

Chantal Akerman, “Dest au bord de la Fiction”, 1995

Chantal Akerman, “Dest au bord de la Fiction”, 1995

Chantal Akerman, Woman sitting after killing, 2001

Chantal Akerman, Hotel Monterey, 1972

Chantal Akerman, Hotel Monterey, 1972

Chantal Akerman, Saute Ma Ville, 1968