In her art practice focusing on sculpture, video art, installation and photography, Michalina Bigaj explores the relationship between people and nature regarding the nature vs culture divide dominating in the Western school of thought. Instead of accentuating the differences, she seeks to draw “archetypical” analogies between one’s interaction with nature and art.

As a resident at the Prague-based Meetfactory (an International non-profit Center for Contemporary Art), she displayed her works on a group exhibition at the Plato Gallery in Ostrava (The Center of Contemporary Art in Ostrava). Additionally, the Meetfactory’s Kostka Gallery in Prague held her solo show.

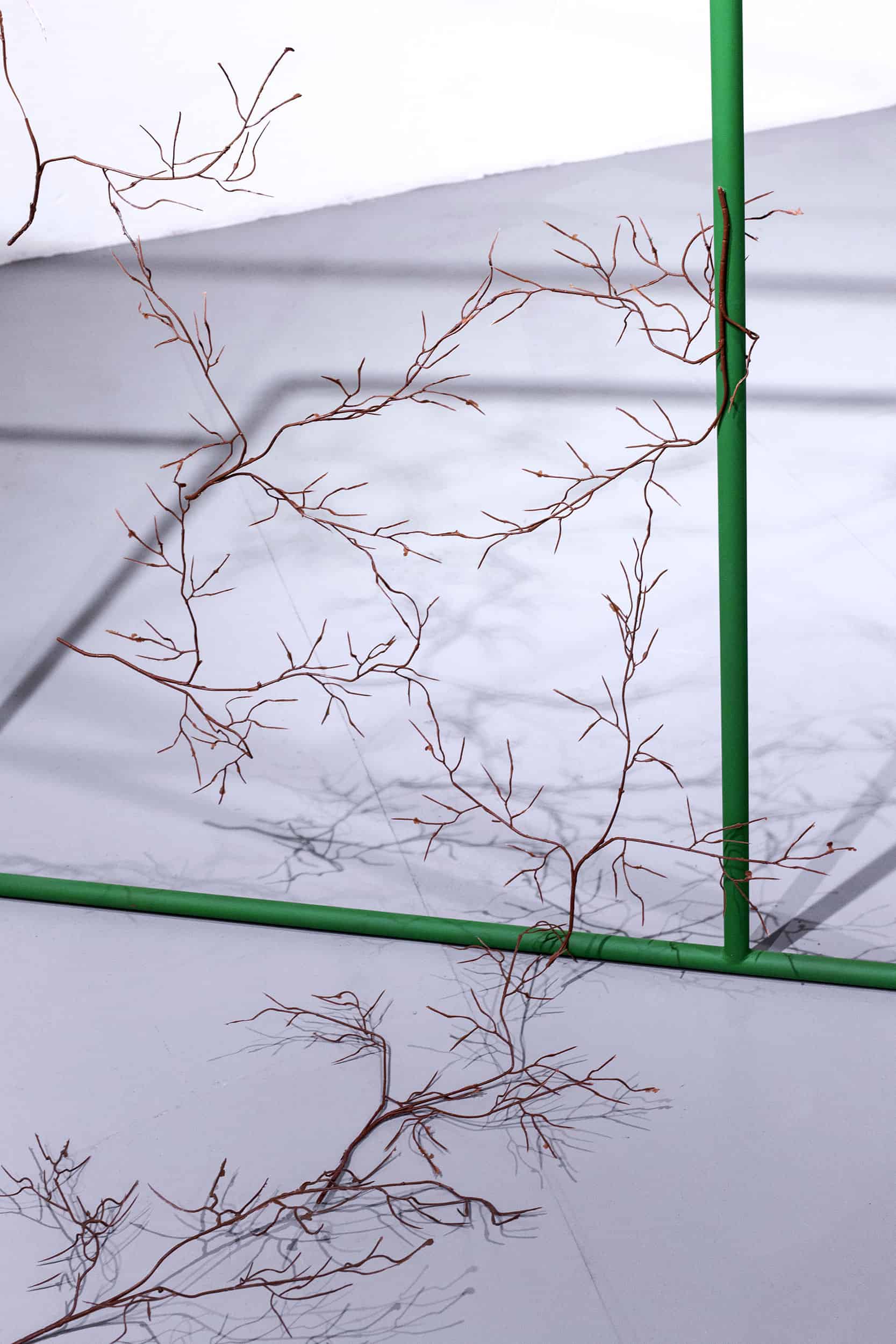

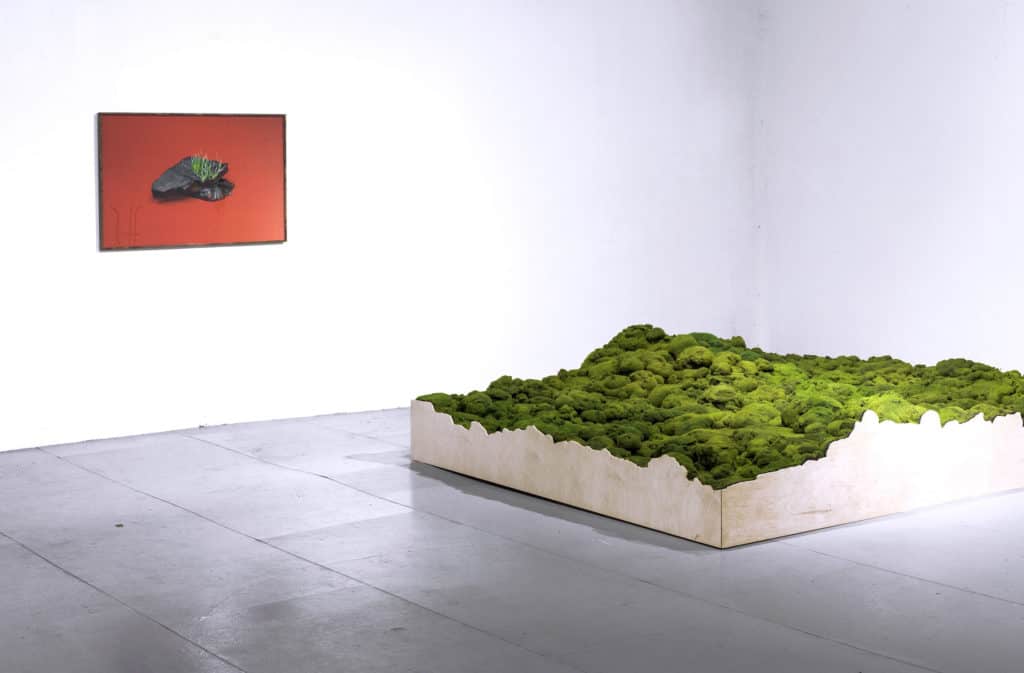

Michalina Bigaj, Disingenuous nature

Michalina Bigaj, Disingenuous nature

AJM: The exhibit of your artworks entitled “Disingenuous nature” opened at the Kostka Gallery in Prague. How exactly did you get there?

MB: MeetFactory announces an annual open call for art projects, which would complement their exhibition programme. In 2016, I submitted my proposal and won. I was invited to participate in the three-month residency programme before an opening, which allowed me to work on the pieces in the studio.

AJM: How did the Meetfactory residency impact on your growth as an artist?

MB: To be honest, I found the direct contact and continuous support of the production team, as well as my stay on location extremely valuable while planning and arranging the exhibition. In three months you’d make yourself comfortable anywhere. The rhythm of my day has stayed pretty much the same after I settled into a routine in Prague. There are days in which I get up, eat some breakfast, work all day long and go to bed. That’s it. The loss of focus can have dire consequences. Therefore, I try to spend time in the studio every single day, even if I’m perfectly aware of the fact that all I’d have to do is answer some emails because I’m not working on any particular piece at the moment. Routine imposes discipline, which is hard to maintain during residency. Obviously, you’d want to see the sights, meet new people and inspect the art scene. The institution always pads your schedule, organises a number of meetings with curators and other events, which, though distracting, provide a great sense of balance.

Michalina Bigaj, Disingenuous nature

AJM: In Prague, you must have come across other young artists who stayed in the Meetfactory. The residents always see each other in the studios and exchange ideas. Did any conversation result in a collaborative art project?

MB: Lucia Kvočáková and Piotr Sikora, curators of the artist-in-residence programme, suggested that the residents should stage a joint exhibition unrelated to their independent art projects which would be the perfect addition to the open studios’ initiative at the Meetfactory – the event designed for the audience’s studio visits. The idea was to travel to Ostrava and organise a pop-up art show inspired by “8 Women,” a film by François Ozon. We hung out together for a few days and orchestrated the event in collaboration with the local Plato Gallery. Anyway, I find Ozon’s film deeply misogynistic. Those eight women’s entire lives revolve around one man, “head of the family” whom they usually only mention in conversation. Their delusion of imprisonment and isolation, alongside the man’s figure, serve as “the framework” of sorts. For this reason, I created a site-specific art project, namely window bars that referred to the scene, in which the characters talk by the window. Ostrava’s central districts experience depopulation. The storefronts of empty retail spaces are filled with their remnants. The Plato Gallery leased one of those venues, supposedly a former coffee shop, for the duration of our exhibit. Surprisingly enough, my mounted window bars blend in with the façade seamlessly.

AJM: I’ve been observing your art practice for several years now. In my opinion, your tenacious, creative approach towards specific themes, including the nature-culture divide (i.e. your leitmotif), certainly deserves some praise.

MB: This juxtaposition is definitely the motif I’m most drawn and return to, similarly to the equally significant and yet less conspicuous notions of oppression and deception. Furthermore, I relish in the depiction of the outdated widespread belief in the ontological polarity between culture and society, which has already been reversed. Social awareness of modern scientific disciplines, such as posthumanism, has raised. Consequently, society members begin to realise that their stance on the binary divide is in fact unsubstantiated. There’s nuance to the correlation between the two. Whereas, the unwavering view that an individual is an autonomous entity influenced by neither culture nor society strikes me as archaic and obsolete. My point of departure is the scrutiny of the culture-nature relation from the anthropocentric perspective, which we often assume unwittingly.

AJM: You mentioned the ideas of oppression and deception, which caught your attention. The oppressiveness of nature seems to have manifested itself strongly in your previous exhibition entitled “Island” that we organised together back in 2016, at the Art Agenda Nova Gallery in Kraków…

MB: My emphasis on the ruthless aspects of nature stems from anthropocentrism. In her book “Time Travels: Feminism, Nature and Power”, Elisabeth Grosz makes an acute observation that culture is inextricably linked to nature, which constantly challenges its state. People should re-evaluate the way in which they coexist with other beings and objects if humanity isn’t the single most important piece of the puzzle. Often, my works of art embody an anthropomorphic form of nature that plays the role of a villain who misleads us and interferes with our lives. The art show you mentioned implied this oppression. My works displayed on the Island exhibit represented with a hint of irony the uncontrollable force of nature that should be reckoned with regardless of the advanced technology at our current disposal. For instance, the work entitled “Ash Cloud Moves East” was based on the newspaper article describing the disruption across Europe caused by the eruption of the Eyjafjallajökull volcano. In this case, we witness a role reversal. Nature is a culprit, while humanity remains helpless. My earlier project “30 Days for Nature,” which examines similar themes, includes a series of photographs depicting the traces nature left on my own body. What I tried to do was to emulate documentary photography’s style, especially images from a real-life autopsy and crime scenes.

Ash Cloud Moves East, wood, acril, basalt rock dust, 130x90x106 cm, 2016

AJM: I wonder how you would define the phrase ‘deception in art.’

MB: And I wonder whether the category of deception is even applicable to contemporary art. I doubt that. What springs to mind when I dwell on the concept is merely a deceptive creative process, a kind of disingenuousness, volatility, willingness to cut corners. On the other hand, the more I really think about it, the more I’m convinced that getting off the beaten track can bring fascinating results.

AJM: What I meant was a deception of the viewer and the game you play. Your works of art highlight tensions between the two contrasting notions, such as the artificial and natural, both in the figurative and material sense.

MB: People’s utilisation of nature’s resources and their aspirations towards it compel me. The key is to unearth weird aesthetically pleasing objects that are just simulacra as opposed to genuine nature. I was preoccupied with those issues while arranging the show “Disingenuous nature.” The series of my photographs documented the objects I made by following ridiculous online DIY tutorials, e.g. “How to make a PVC fleshing beam.” On the one hand, the activity could be interpreted as the appropriation of nature and disregard for its materials, which undergo transformation to suit one’s purpose. On the other side, it stands for longing and exemplifies a strategy to produce natural substitutes, which we might resort to in the foreseeable future due to nature’s inaccessibility. The garden as an artificial and yet natural construct, was also germane to the exhibit. For instance in art history, the garden has always been associated with the nature vs culture divide.

AJM: What proved to be a challenge in the exhibition’s arrangement? Was it perhaps the gallery space itself?

MB: Yes and no. From my standpoint, a demanding space, an almost ideal cube of the Kostka Gallery’s interior, corresponded perfectly well with my concept of a botanical garden. In principle, such places are designed for maintenance and growth of specific plants for scientific, educational, protective and recreational purposes. Untarnished mutating epitomes of nature are grown in pristine isolated conditions. However, their chance at evolutionary development is forsaken. Any garden’s principal goal is to satisfy people’s specific need for aesthetic experience, which bears connotations to the role fulfilled the white cube or cultural institutions and art galleries in general. I believe there’s certain correlation between those places.

AJM: Most artists never disclose their plans for the future, but I’m going to ask you about them anyway: aren’t you already bored with nature? (smile). Is there any creative potential left for you to tap into?

MB: There is! The sky is definitely the limit.

AJM: Thank you for the conversation.

Michalina Bigaj, Disingenuous nature

Michalina Bigaj, Disingenuous nature

Michalina Bigaj, Disingenuous nature