We can recently observe an avid interest in the topic of flora among artists and curators. Does this “green revolution” result from the upcoming climate disaster, or does it originate from other processes? Together with Aneta Rostkowska, a curator, we are talking about her most recent exhibition at Temporary Gallery in Cologne devoted to these areas of contemporary art.

Floraphilia. Revolution of Plants photo: Tamara Lorenz

Floraphilia. Revolution of Plants, photo: Tamara Lorenz

Floraphilia. Revolution of Plants photo: Luise Fluegge

Marta Kudelska: The starting point for our discussion is the exhibition you have curated, entitled “Floraphilia. Revolution of plants.” Before we move on to discussing it, I would like to ask a few questions about your past. Your career as a curator began in Kraków, where you took part in such initiatives as Zbiornik Kultury or Bunkier Sztuki gallery. How did you get to Temporary Gallery Centre for Contemporary Art?

Aneta Rostkowska: After I graduated from de Appel arts centre in Amsterdam I returned to Kraków to continue my work at Bunkier Sztuki gallery. I was engaged in the Baltic Triennialfor which I created a large group exhibition entitled “A Million Lines” together with Virginija Januškevičiūtė. In 2016 I moved to Cologne to collaborate with Ekaterina Degot and David Riff at the Akademie der Künste der Welt. This relatively young institution, established in 2012, is dealing with such issues as the heritage of colonialism, the current political situation or multiculturalism, just to name a few. Back then I was interested in working with an institution which is smaller than Bunkier and has a distinctive social and political profile. It turned out to be a very valuable, developing and inspiring experience: I began to carry out a more global curatorial research, I extended my knowledge on post-colonial theory, the history of colonialism, racism and the feminist movement. I realised that my philosophical studies in Kraków did not cover those topics at all. After nearly two years of working at the Academy I took part in a competition for the position of a director of a small contemporary art centre in Cologne called Temporary Gallery, which I managed to win. In my work I try to draw on my experience gained during my time at the Akademie der Künste der Welt, Bunkier Sztuki and de Appel arts centre.

Marta Kudelska: “Floraphilia. Revolution of Plants” which you are currently showcasing in Cologne was created as a result of a large-scale international project. Can you tell us a bit more about it?

Aneta Rostkowska: Yes. The idea for the exhibition was born while I was still working at the Akademie der Künste der Welt taking part in a larger project entitled “Floraphilia: On the Interrelations of the Plant World, Botany and Colonialism” financed by Kulturstiftung des Bundes (German Federal Cultural Foundation). The purpose of the project was to reflect on the political history of plants, their interrelations with the history of colonialism, botany and botanical gardens. The first exhibition organised as part of the project, held in Cologne in 2018, was entitled “Floraphilia. Plants as Archives.”

Floraphilia. Revolution of Plants photo: Tamara Lorenz

Marta Kudelska: How do you think this title should be understood? What may these plant archives hold?

Aneta Rostkowska: If we take a closer look at the history of humanity, we can notice that there were a lot of plants which affected human fate and ecology at a large scale; think about, for example, cotton, coffee, sugar cane, cinchona, rubber tree, or poppy. In the history of European colonialism plants played a vital role because their transportation to and from colonies was the source of huge profits. We know that colonies were an excellent location for growing tropical plants which could not grow in European climates. They also served as new outlet markets, and colonizers were drawing profit from monopolising trade, introducing imports taxes and licensing exports. Plants were also important in the history of slavery – British plantation owners in the Caribbean transported jackfruit from Tahiti as cheap and high-yield food for their slaves. Botany played a fundamental role in colonial control: botanists studied notes made by merchants, and received seeds and plant specimens from them. A good example of a plant which was an organic archive, in the literal sense of the word, is a wild almond tree growing in Kirstenbosch botanical gardens in Cape Town. It is a remnant of a 25-kilometre-long hedge planted in 1659 by Jan van Riebeck, employee of Dutch East India Company. The hedge was to serve as a barrier protecting against the native inhabitants of the area, Khikhoi and San tribes, stealing cattle from the colonists. This seemingly harmless plant became a tool of colonial violence. Judith Westerveld tells its story in her artistic works.

Marta Kudelska: Where did the idea for “Floraphilia. Revolution of plants” come from?

Aneta Rostkowska: While working on the “Floraphilia. Plants as Archives” exhibition I studied the history of colonial expansion intensely. It is a dark history, full of human suffering, taking away all hope. I distinctly remember the history of British colonisation of India and opium wars, and what happened in Africa, for example the massacre of the Herero and Namaqua people by the German Empire between 1904 and 1908. It’s a pity that not enough time is devoted to this in schools. In fact, some of the first concentration camps were built by the British in Africa during the Second Boer War. By the way, this war marked the beginnings of Scouting, as one of the British commanders, General Robert Baden-Powell, based on his experience gained during the time, wrote a book about military reconnaissance for young boys which later became inspiration for the Scouting movement. When I was engaged in the Polish Scouts, nobody mentioned that the beginnings of the organisation were related to British colonialism.

Anyway, the history of plants in the context of colonialism history is very important, and after presenting its fragments in the form of an exhibition, I wanted to reflect on the issue as a curator, looking more into the future. I wanted to search for art works which bring a bit of hope. This is how I came up with the idea of reversing the traditional hierarchy, also present in philosophy, where plants are less complex beings and less interesting than humans, and to treat them as an inspiration for political activities.

Saddie Choua, Floraphilia. Revolution of Plants, photo Aneta Rostowska

Marta Kudelska: Exactly, your exhibition refers to various forms of relationships between men and plants, and to their revolutionary potential. In your opinion, what is this new “green revolution”?

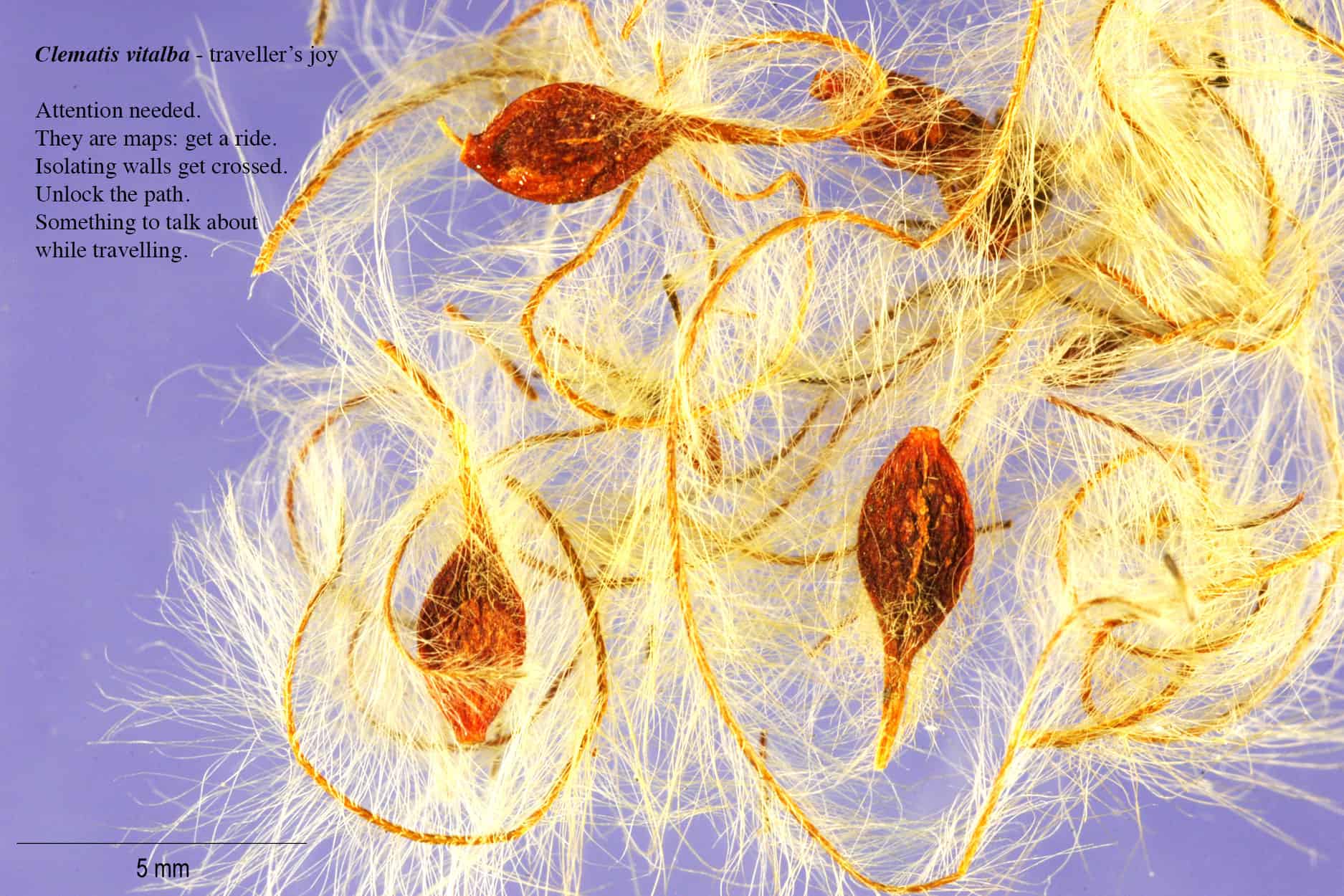

Aneta Rostkowska: It includes noticing various properties of plants which can serve as inspiration to us, encouraging us to think of plants as “teachers”. Of course, it is my hypothesis, a type of a proposal partly inspired by some of the texts written by philosopher Michael Marder. Resilience, the ability to adapt or communicate, and indifference to any state boundaries can serve as excellent examples here. For instance, Canada goldenrod instils in us an element of disobedience, Japanese rose teaches us how to evolve depending on the surroundings, and calamus becomes a symbol of renewal and purification. Plants are community beings by nature – they are not individuals clearly distancing from one another. Their identity is deeply pluralist: from roots being the home to decentralised intelligence to interdependence with other organisms. Isn’t it a cure for contemporary individualism?

Marta Kudelska: Tracing back the history of humans we can see that it is closely related to the history of plants. Humans conquered the natural environment, accumulated and utilised various plants – cotton, chocolate, tobacco… A growing criticism of this state of affairs is becoming increasingly intense. Why did you decide to deal with this topic?

Aneta Rostkowska: I believe that by understanding this history, we will be able to comprehend current events better. The history of plants is the history of colonialism and capitalism and its economic foundations. Many contemporary state boundaries and related political conflicts, for example in Africa, have their origin in colonial expansion and the resulting division of spheres of influence. Although colonialism officially ended decades ago, today’s wealth of western societies is to a vast extent based on the continuous exploitation of former colonies in the name of capitalism, consumerism and “free market” ideology. An additional reason why I took on the topic is a growing interest in plants we can currently observe in contemporary culture. Instagram is full of photographs of plants. It is not a negative phenomenon, but I think that we can adopt a more in-depth perspective, without treating plants merely as decorations for our houses, but perceiving their complexity and treating them with respect. In this context, I have drawn great experience from reading texts and poems by scholar and poet Urszula Zajączkowska, and some of them were printed in a folder accompanying the exhibition.

Dagna Jakubowska, Floraphilia. Revolution of Plants, photo: Luise Fluegge

Dagna Jakubowska, Floraphilia. Revolution of Plants, photo: Luise Fluegge

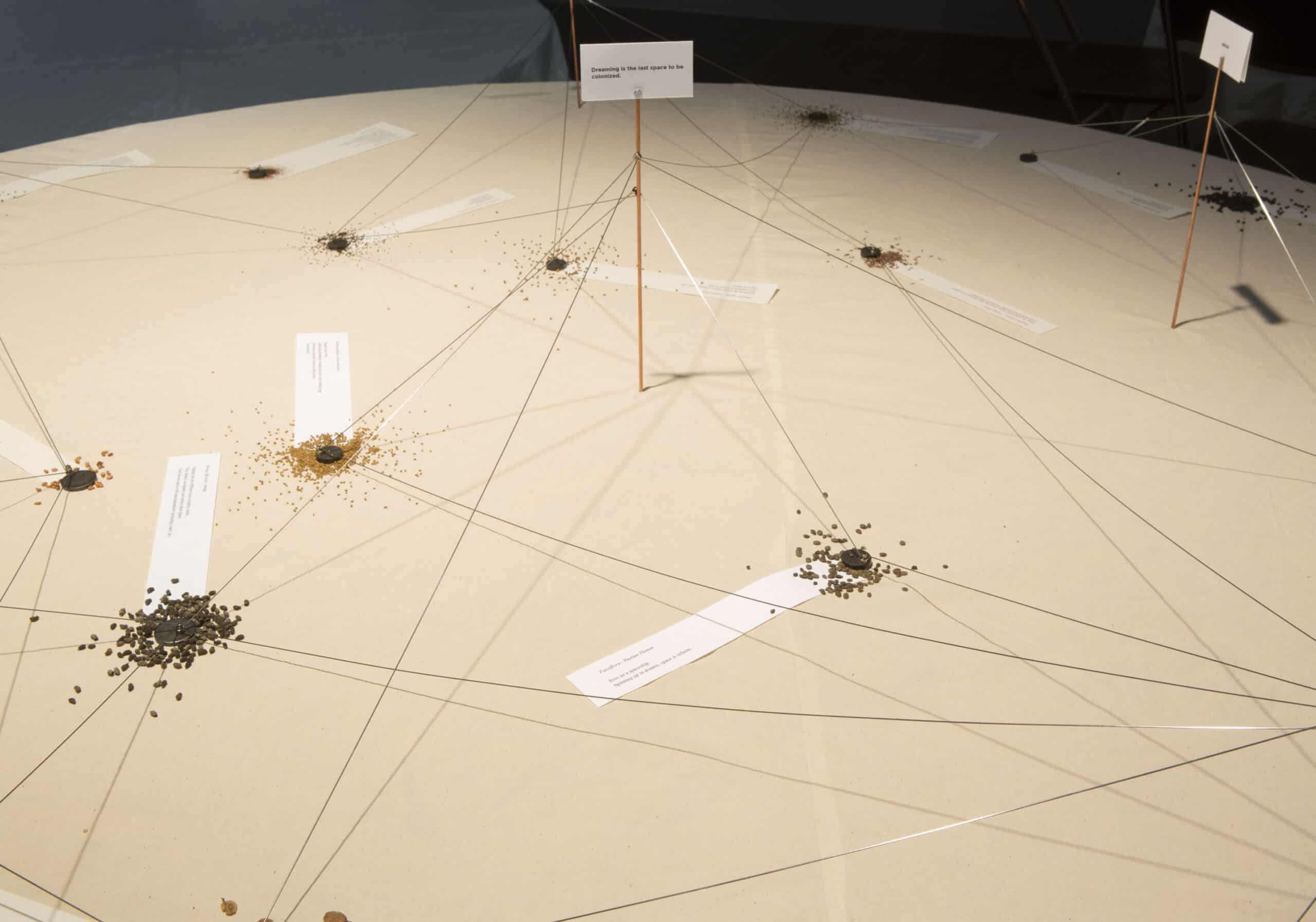

Marta Kudelska: The design of the exhibition itself looks quite incredible. On the one hand it has an element of a strange, mysterious ritual, while on the other hand it brings to mind a strange avant-garde restaurant. Where did you get that idea from?

Aneta Rostkowska: Together with the author of the design, Mateusz Okoński, we wanted to refer to rituals and ceremonies present at the exhibition. The works were showcased on tables covered by tablecloths embroidered with plants appearing at the exhibition. The tables resemble small altars, places for communion or meals. This is exactly what happened – during the opening night, when Dagna Jakubowska and Joannna Gawrońska-Kula, as part of their performance offered dishes made of invasive plants. Perhaps this way we managed to take over some of the properties of those plants, their resilience and tenacity, for example (laughing).

Marta Kudelska: I would like to talk about the works we can view in the exhibition. One of them is an impressive installation by Bianka Rolando. It refers to the ritualistic, magical side of nature. For a few years now interest in herb cultivation, witchcraft and magic has become clearly visible in mass culture. Dagna Jakubowska as you have mentioned is taking up similar topics. Do you think that today’s reality is disappointing, and hence this primaeval need to build communities?

Aneta Rostkowska: Yes, I agree. I think that we are searching for other, more holistic and emotional ways to foster our relationship with nature. A relationship in which nature is treated on a par with humans. I interpret it as a reaction to the environmental crisis. During the exhibition it came to my mind that in a sense, today’s science confirms a lot of pre-modernist beliefs. According to them, nature is also a complex being close to humans. Humans are also treated there in an unprivileged way. In this context, the works by Candice Lin, presented during the exhibition, seem interesting. The author presents a contemporary scientific theory, the five kingdom classification (according to which all living organisms can be divided into fungi, plants, animals, bacteria and protista) in the form of esoteric diagrams and treaties.

Marta Kudelska: Our image of nature was formed by the language of romanticism, its symbols and iconic examples, as well as by the enlightenment and positivist views that nature is something we should control and utilise. Which of the works you present have made the strongest impression on you?

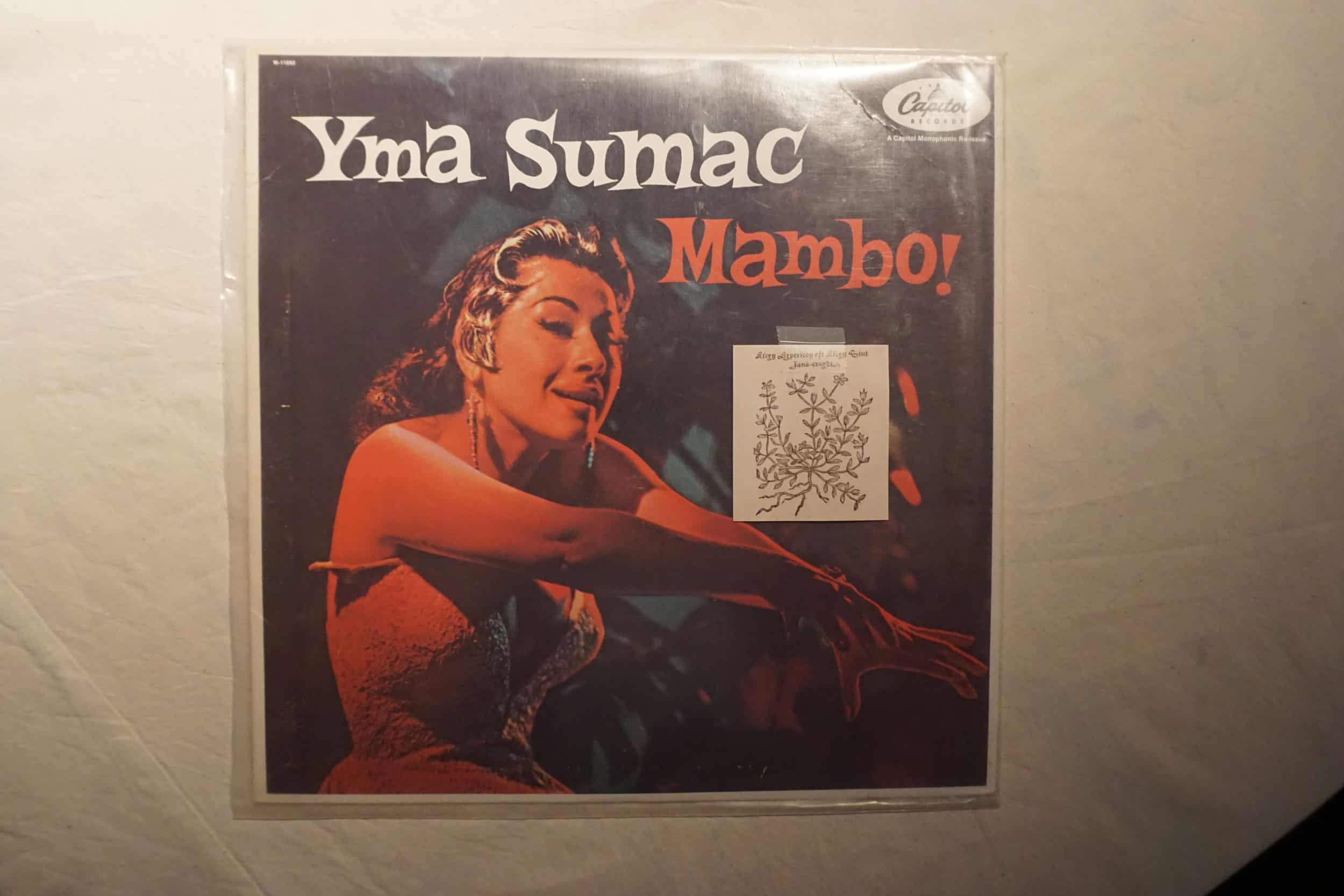

Aneta Rostkowska: It is difficult to choose because I am a fan of all the presented works! You are welcome to learn more about the exhibition online, in the form of a guided tour on YouTube, playlist on Vimeo (Password: Temporary-Gallery) and a folder with photos of all the works and information about them. In the context of our interview, I would like to mention the works by three artists, Milena Bonilla, Saddie Choua and Ines Doujak. Milena Bonilla dealt with a herbarium kept by Rosa Luxemburg who, in addition to politics, had had a keen interest in botany. The artist prepared a political interpretation of plants from the herbarium, and created a type of mind map, or a spatial model of a thinking pattern, marked out by plants. A beautiful work! In turn, Saddie Choua created a work inspired by a 16th century herbarium where plants were classified by their external features. Noticing that a similar way of thinking is present in racist views, she combined pages from the book with the pages taken from National Geographic magazine, which not so long ago formally apologised for disseminating racist stereotypes about people living outside of Europe. She added recipes for various plant-based medicines which can help treat trauma caused by racism. A very moving, profound work. Ines Doujak confronts us with Eshu, a spirit mediating between the world of divinity and humanity, who brings us a bouquet of psychedelic plants. We must decide for ourselves if the spirit is good or evil.

Milena Bonilla, Floraphilia. Revolution of Plants photo: Tamara Lorenz

Milena Bonilla, Floraphilia. Revolution of Plants photo: Tamara Lorenz

Marta Kudelska: What did it mean for you, as a curator, to work on this exhibition? Did any thread occur during this work which you would like to continue in the future?

Aneta Rostkowska: The work on this exhibition was very pleasant, maybe because the artists’ works are full of passion and engagement, and the artists themselves are fascinating figures. I had a chance to work with some of them before, and I hope that we will meet in the future more than once. It is a great honour to keep in touch with people who not only take up important issues, but are also able to give them a sensual form, engaging our emotions. I will surely continue to elaborate on these topics in the future, and I am planning a symposium about Lynn Margulis (the scholar who inspired Candice Lin’s works) next year, an international research project on the interrelations between botanical gardens, botany and colonialism, and publications summarising all the events and exhibitions which took place.

Marta Kudelska: Finally, please tell me about your favourite plant.

Aneta Rostkowska: During the pandemic, I started a permaculture vegetable garden so I’m currently fascinated by all edible plants growing there – cucumbers, tomatoes, pumpkins, potatoes and Jerusalem artichoke.

Milena Bonilla, Floraphilia. Revolution of Plants photo: Tamara Lorenz

Temporary Gallery

Centre for Contemporary Art

(Verein zur Förderung des Kunststandortes Köln e.V.)

Mauritiuswall 35

50676 Cologne