Jakub Woynarowski, portrait with „Fiat Lux” vinyl record by Quadratum Nigrum collective (Jakub Woynarowski, Jakub Skoczek, Mateusz Okoński), 2015, photo: Justyna Gryglewicz

Jakub Woynarowski is a creator of visual essays, comic books, films and installations. He is also involved in the so-called practice of gonzo curating. His interests include alchemy, masonry and the margins of art history. His works were displayed in the Polish Pavilion at the 14th Venice Biennale of Architecture in 2014. We had a chance to talk to the artist about his past artistic activities and projects while visiting the exhibition he is taking part in, Conversation Piece | Part IV – Giant steps are what you take, organised at the Fondazione Memmo.

Marta Kudelska: To begin our conversation, I would like you to describe the art gallery of your dreams.

Jakub Woynarowski: To start thinking about this topic from the right point of view, we ought to ask ourselves the question of whether a gallery has already become an outdated concept. The world of art still dwells on the concept of the white cube, which is attributed to modernism and the first avant-garde since it began over a hundred years ago. A white cube transferred from the cultural centre to the peripheries can be transformed into a border post, an object delimiting a territory or even a colonization driver. In this respect, the cube is isolated from reality and resembles a temple. It is worth mentioning here that the Latin word templum means “a defined space separated from the outside”. The white cube is definitely a symbol of modernization, but there is something alluringly archaic about it at the same time. I tend to draw analogies between the white cube and Stanley Kubrick’s monolith or UFO – which arrived at a foreign place to collect samples, conduct research and then return home after finishing the assigned job.

All this makes me think about the network of Artistic Exhibitions Bureaus which existed in Poland under the socialist regime. Interestingly enough, many of the institutions which formed this network survived the political transformation and continue to successfully operate until present day. Each of these Bureaus was supposed to function as a “tool” aimed at transferring information from the centre to the peripheries. Here we should ask ourselves whether information used to flow in the opposite direction as well. In fact, does it flow in the opposite direction nowadays? Personally, I truly wish information was transmitted both ways. In my opinion, this is only possible when an institution ceases to be a “colonial bastion” and starts to operate like a black box which collects information. It should not only encode input, but also create certain output data.

Jakub Woynarowski, „Characteristica Universalis”, installation view, Palazzo Ruspoli / Fondazione Memmo, Rome, 2017, photo: Jakub Woynarowski

So, going back to your question, the gallery of my dreams is a vibrant and organic place and an inherent element of the local environment. It should refrain from covering itself with reinforced lining, but, nevertheless, it should revolve around a defined nucleus. The function of these external layers covering the nucleus should be to allow it to process the impulses coming from outside spaces more efficiently. I would like to mention here a metaphor which Janusz Bogucki, who is considered the first Polish art curator by many, came up with. Dreaming about his artistic magnum opus he invoked the notion of “mycelium”. As unconventional as this analogy may seem, it is also very appropriate. Mycelium has a very delicate structure but, at the same time, it is the vegetative part of a fungus – the most resilient and longest-living organism on our planet. Bogucki’s concept was quite utopian and never came to fruition. He was hoping for a combination of house, art gallery and temple which would form a coherent whole. It would develop over time and would have no defined borders. To a certain extent, it would resemble Kurt Schwitters’ Merzbau. The whole structure was supposed to be open. Nevertheless, its “animator” considered that a common centre would exist and organize everything from within.

Marta Kudelska: Do you think that institutions need an “anchorage”? What I mean by that is a certain element which resonates and influences the entirety.

Jakub Woynarowski: I think they do. The total decentralization of institutions seems a bit unrealistic to me. I don’t think that that’s possible taking into account certain psychological aspects of human existence. For humans it is natural to be a little vain. They need a stage where they can present themselves to others. The world of art is organized in a structure which resembles a network. However, this network has its “core”, which makes artistic activities of any individual purposeful and provides a distribution channel to creators, which basically means that it makes creators visible. Nevertheless, the core does not need to be represented by a closed, hierarchical and oppressive structure which would only allow for our passive acceptance. In my opinion, in order to allow a bidirectional flow of creative energy we need art institutions which are open and whose structure resembles the porous texture of a sponge. Therefore, art institutions should be accompanied by project space galleries and should support other ephemeral initiatives. They should limit bureaucracy to the greatest possible extent and be more sensitive to the input from outside. By nature I am a tease, so it seems to me that such a pluralistic model should also include the conservative white cube which would be considered a modern incarnation of “the temple of art”. I think that extreme elitism also has something appealing about it. Just think how alluring it would be to organize an exhibition for only one specific visitor (laughs).

Jakub Woynarowski, „Variety”, digital print, 2016

Jakub Woynarowski, „Museum of the Void”, digital print, 2016

Marta Kudelska: Let’s talk a little bit more about nature, because you have been quoted as comparing an art gallery to a garden.

Jakub Woynarowski: When I made this comparison I thought of two outdoor design concepts, namely the French formal garden and the English landscape garden. These two gardens look totally different at first sight, but, in fact, their “content” is the same. In both cases, living tissue and nature are manipulated to achieve a desired outcome. The French formal garden is about taming nature and creating geometric shapes, drawn in accordance with the rules applicable in maths. Such gardens were often surrounded by a wall, which gave the space inside a prestigious character. Such an approach corresponds to the idea of culture as available only to aristocrats and members of the elite. Let’s not forget that in the past, gardens were treated as outdoor art galleries where visitors could admire architecture and sculptures. The greenery arrangements themselves were a bit similar to modern land art works.

The English landscape garden, on the other hand, was supposed to imitate wild nature or even be more natural than nature prior to human intervention. Whenever any element was spotted in such a garden which was not typical for a natural landscape, it was removed straightaway. Lancelot Brown, an architect living in the 18th century, was one of those who elevated such activity to the rank of art. Nowadays we would probably call him a conceptual landscape engineer or land art conceptualist. Matthijs van Boxsel provided a fascinating description of Brown’s activities in a chapter of his book The Encyclopedia of Stupidity.

„Mad Tea Party” (curated by Aneta Rostkowska and Jakub Woynarowski), „Opening Ceremony of the Roaming Assembly #16”, documentation of lecture-performances by DAI students: Alejandro Ceron, Eric Peter, Samantha McCulloch, Leeron Tur-Kaspa, Lea Gübner and Anja Khersonska, Christuskirche, Cologne, 2017

There is a question here which automatically comes to our minds, namely, what was so special about these landscape designs that would make the audience admire the work of a landscape architect? What was there to be admired if, in fact, the design was supposed to remain unnoticed in order to be considered “natural”? This essential element which made gardens of this type “stand out” was the demarcation line between the garden and nature. Obviously, it was not acceptable to build a traditional, “artificial” fence or wall around the garden area. But can we say that we created a garden if it has no definite border separating it from its surroundings? This is where a hidden landscape border, the so-called ‘ha-ha’ originated. It was a hidden retaining wall aimed to prevent access to the garden from the “unauthorized”, i.e. local residents and animals. This modern landscape design element allowed an illusion of transparency and unrestricted access to the garden area.

I have an impression that the ha-ha corresponds to the modern concept of art whose creators try really hard to make it resemble reality. There is a continuous debate about numerous possible modifications which would allow for the destruction of the currently existing “artificial” barrier. At the same time, the fact of art being autonomous and having a status which differentiates it from everything else in the contemporary world is constantly being emphasized. This, of course, contradicts the avant-garde declarations I just quoted. It turned out that the invisible borderline between art and everything else is still desirable. This borderline is our imaginary ha-ha, a practical tool which helps us organize the way we perceive reality.

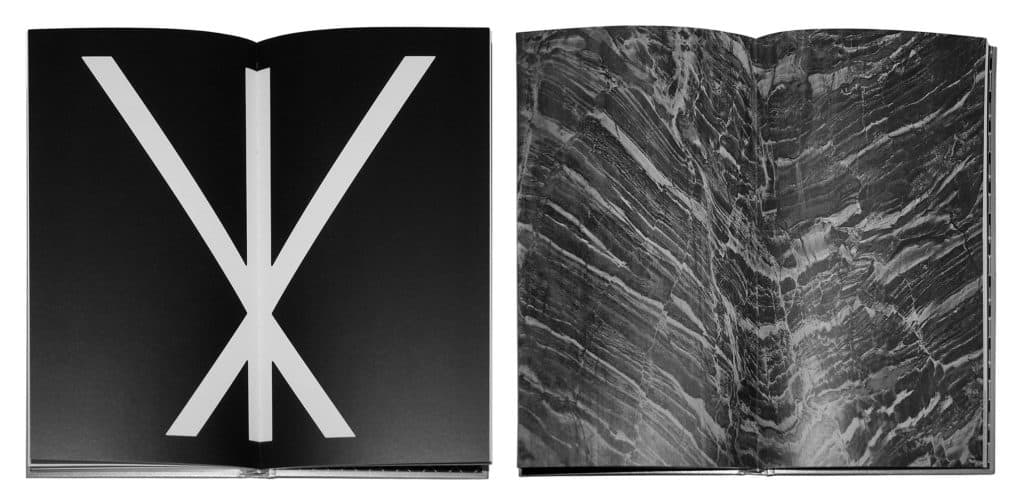

„Impossible Objects”, catalogue designed by Jakub Woynarowski, 2014

Marta Kudelska: Your activities also include those going beyond the enclosed space of institutions. One of them is gonzo curating.

Jakub Woynarowski: I have been interested in various types of artistic activities and the related channels for content transmission. For me, traditional gallery events, typical for institutionalized artistic activity, are only one of many possible ways of presenting art, and my work on it has been widely available. I am the author of graphic novels like Dead Season, based on twelve works by Bruno Schulz, and I also create visual essays. One of my projects of the latter type was Corpus Delicti which was dedicated to the activity of Walerian Borowczyk and was created in collaboration with Kuba Mikurda. Currently, together with Kuba, I am working on the movie Love Express, which would supplement our book in its own specific way.

Simultaneously, I am part of an Ubu Lab research project at the Jagiellonian University in Krakow. The project focuses on using digital technologies in creating paraliterary narration. One of these narratives is a VR project entitled Stilleben. I am working on this project together with Jan Argasiński. We try to combine virtual exhibition space with an exploratory game.

The biggest project “from outside of a gallery” which I have been involved in is focused on gonzo curating. I have been developing the concept since 2012 in cooperation with Aneta Rostkowska. We started at different points but met somewhere in the middle, in a territory familiar to both of us. She was a curator who used artistic strategies in her work, while I was an artist interested in curatorial activities.

The underlying idea of this project is changing the perception of reality through narration with a proper structure. What is important here is the fact that this expansive storytelling does not require any physical interference in the space as it exists. Thanks to that, we can treat the world as our medium and apply the mechanisms of creating Duchamp’s readymades on a large scale. Obviously, gonzo curating could be perceived as institutional criticism, but our activities are not supposed to be revolutionary and we do not try to propose any radical changes. What we try to do, on the other hand, is to activate an existing potential which seems not to be utilized to a satisfactory extent. We try to find our own way within the system which tends to be oppressive and secluded despite its declared openness and creativity. Gonzo curating allows us to correct the existing reality in our own way.

Jakub Woynarowski, Aneta Rostkowska, ”The Strange and Terrible Saga of the Jindřich Chalupecký Award”, lecture-performance, Národní Galerie, Prague, 2017

Marta Kudelska: One of the manifestations of your approach was establishing the Wawel Castle Contemporary Art Centre.

Jakub Woynarowski: Indeed, the Contemporary Art Centre was an initial gonzo project and a space for experimenting. It allowed us to test the ideas we put forward in 2012 in our Gonzo Applied Arts manifesto. The Centre is a para-institution and it operates on Wawel Hill in Krakow. Wawel is a museum space which does not allow contemporary art activities. However, it turned out that Wawel, despite its symbolism and serious nature due to the material assets collected there, is the perfect space for more ephemeral creative initiatives.

The Wawel Castle Contemporary Art Centre is a site-specific project embedded in precisely defined surroundings. Our starting points were all the constituent parts of the complicated structure of Wawel. I had both movable and immovable artefacts in mind, starting from architecture and museum collections, destroyed objects, and including plants and animals, as well as the employees at Wawel. The “procedure” we apply there resembles that of appropriation art. We invite artists and curators to select objects which they consider works of art. They “crave” by using narration, and not physically interfering in the space itself. Storytelling influences the way that certain objects are perceived. It brings them closer or further apart from one another, emphasizes them or makes them invisible. There is one condition that we all try to follow, which is the probability rule. The created narratives must be credible because we strive to form a temporary community of “followers” who would be as open to irrational superstitions, as to manifestations of hyperrational paranoia. I’ll quote Hunter S. Thompson now, who invented the notion of gonzo journalism: “There was a fantastic universal sense that whatever we were doing was right, that we were winning”.

The Wawel Castle Contemporary Art Centre is a meta-curatorial tool aimed to supervise all these activities. It acts as a partly fictitious and invisible art institution. What is important is the “non-materiality” rule which we apply in our activities on Wawel Hill is a result of the restrictions imposed by the management of the Wawel Castle. These restrictions prohibit any visible interference in the hill’s antique artefacts and surroundings. When we organized the first curator guided tour to present the Contemporary Art Centre’s collection we tried really hard to obtain the management’s approval. Therefore we tried to find a form of activities which would go beyond the restrictions imposed but, at the same time, would not constitute a breach of any of the rules in place. I would like to emphasize that our aim is not to criticize or ridicule this place, but rather to utilize its potential which remains unnoticed by the managers, as well as contemporary artists. Unfortunately, for these artists Wawel remains an embarrassing place to work and create in.

„CCA Wawel Castle”: Magdalena Lazar, „Siew rzutowy mokry”, photoperformance, 2012, photo: Natalia Wiernik

Marta Kudelska: Is it not an embarrassment for you to work at the Wawel Hill?

Jakub Woynarowski: Aneta and I are interested in the similarities between ancient art and modern art. Therefore, it was in line with our intentions to select a historic space and engage in activities which would be creative rather than destructive. We would like to go way beyond criticizing the structures in place. At the Wawel Castle Contemporary Art Centre we try to create something new through developing narration around objects and phenomena which became part of the Wawel Hill a long time ago. We invite artists who appropriate certain elements of this historical space and create their own original tales and stories around them. What we are seeing now is an expanding exhibition and the development of a curatorial tale.

Marta Kudelska: The stories happen at the moment they are being told.

Jakub Woynarowski: True. We have a territorially defined space, so our exhibition cannot grow in the literal sense of the word. However, its structure is becoming increasingly dense because the hidden potential is constantly being released and new references are being found more and more often. As I’ve mentioned before, our activities do not interfere with the “possessions” of the Wawel Royal Castle in any way. We make use of the objects which already exist and we invite artists to cooperate with us. Their work is truly creative and consists of constructing credible stories, usually on the basis of extensive research on multiple levels. It is, however, a question of faith for the outsiders to admit the existence of links which connect the listed components which are created thanks to the stories told by our artists and curators. Multiple activities also take place in order to institutionalize the collected material. The whole structure composed of materials and links resembles a case. It is widely known that institutions’ existence is manifested through numerous authentication procedures which are being created constantly and are becoming increasingly complex. The collection of the Wawel Castle Contemporary Art Centre is still developing and its evolution resembles the existence of a living organism. This development is possible thanks to a creative approach to bureaucracy which allows us to create documents that become works of art themselves. The ability to play with documentation, or “anti-documentation”, is an important part of the identity of the Wawel Castle Contemporary Art Centre. Obviously, the Wawel Castle Contemporary Art Centre does not possess any material assets because the artefacts in place on the Wawel Hill are not owned by us. Nevertheless, our collection exists. (Anti-) documentation constitutes our inventory and is a physical, mainly digital, manifestation of our activity. The team helping us is growing as quickly as our collection. We have an increasing number of international contributors, thanks to whom we are able to amass our symbolic capital. Moreover, we are working on a nomadic artwork collection concept. We organized an ongoing tournée during which our collection is exhibited through short-term leasing of our works to other institutions (e.g. for a period of 45 minutes). Since 2014 our works and achievements have been presented at Vilnius University Imagination Lab, the Kulgrinda art camp in Kartena, the Fire Station Artists’ Studios in Dublin, De Appel Arts Centre in Amsterdam, California College of the Arts in San Francisco and numerous other institutions. We are also considering launching an anti-residency programme; its participants would be prohibited from visiting Wawel Hill and will be requested to create their artworks in a remote working environment. As we all know, restrictions boost creativity (laughs).

Jakub Woynarowski, Aneta Rostkowska, „CCA Wawel Castle”, lecture-performance, Cracow, 2012, photo: Weronika Szmuc for KBF

Obviously, the Wawel Castle Contemporary Art Centre is not the only gonzo project that we are involved in. Other activities include the audio vernissage in a radio broadcasting station in Krakow, gonzo workshops at De Appel Arts Centre and an anti-curator guided tour of the existing exhibition of works by the artists who were awarded the Jindřich Chalupecký prize. This exhibition and our accompanying tour were both organized at the National Gallery in Prague. It is worth emphasizing that we are not involved in any guerilla-type activities, and that we cooperate with institutions through official channels. In most cases, all applicable documentation is filed. Thanks to that, we have so many new acquisitions for our paperwork collection (laughs). Our latest gonzo event was a performative conference entitled Mad Tea Party, in October 2017 in Cologne, Germany. It was organized in cooperation with Akademie der Künste der Welt and the Dutch Art Institute. We selected Christuskirche as the venue for the event, which is an active Protestant church which resembles the white cube to a great extent. I think that the idea of “pure” temples introduced during Reformation resembles the contemporary art gallery model. In both cases, people strive to create neutral surroundings or secluded spaces which would allow for uninterrupted expression of spirituality in its various manifestations. We used the natural potential of church space for our performance. We presented a kind or modern ritual in which Bible verses were replaced by certain manifestos from the 20th century, for e.g. a manifesto by Robert Smithson. Our activities are perfectly summed up in a video performance entitled Fugitive Mirror, which was prepared for us by Alexander Nagel in collaboration with Amelia Saul. Alexander Nagel is the author of the famous book Medieval Modern in which he draws shocking references between medieval religious art and conceptualism of the 20th century. I think that it is inspiring to think about similarities between the church and the world of art, and I hope that this topic will be extensively elaborated upon in future projects.

Jakub Woynarowski, „Hortus (I)”, digital print, 2015

Marta Kudelska: Drawing and illustrating comic books is where you started your life as an artist. Do you still work on projects involving that?

Jakub Woynarowski: Of course I do. When I was a student, I considered drawing the primary media for contact with the world around me. It was always a starting point for other, intermedia artistic activities. Drawing is a very functional tool since it allows you to record your thoughts immediately and structure your inspirations, so that you create an intelligible “visual narration”. The more complicated structures I encounter, the more willing I am to make notes in the form of drawings. Apart from the “structural” method of recording things through drawings, I also utilize the aesthetic potential of drawings in their classical form. My appreciation for the classics is proven by the topics I develop in my artistic activity and the fact that I am balancing between ancient art and contemporary art, avant-garde and post avant-garde. I create apocryphal works, which connect two remote areas, just as bridges do. My pictures represent ancient art from a purely formal point of view, but, at the same time, they are manifestations of conceptual experiments in contemporary art. I learned the classical rules of drawing, which allow me to “forge” certain aesthetics in a credible way. However, in my case, very different content is hidden behind the aesthetics of ancient art. For me, comic books and designs are more elaborate forms of drawings created with a narrative in mind. Graphic design is an important background for my artistic activities. These two means of expression overlap very often in my artistic life. A perfect example here is the project entitled Impossible Objects, which I presented at the Polish Pavilon at the 14th Biennale of Architecture in Venice in 2014. The project was prepared in cooperation with the Institute of Architecture. The central part of the installation was surrounded by a constellation of diagrams and graphic symbols. The installation was supplemented by a catalogue which I designed to play the part of a conceptual object. Thinking about projects in this way is really useful, especially when you treat an exhibition as a form of visual essay, which coincides with my approach.

Jakub Woynarowski, „Impossible Objects”, installation view, The Polish Pavilion at the 14th International Architecture Exhibition – la Biennale di Venezia, 2014, photo: Wojciech Wilczyk

Jakub Woynarowski, „Somnium”, installation view, MeetFactory, Prague, 2015, photo: Jakub Woynarowski

Marta Kudelska: We can say that your art revolves around magic, secrets and sinister motives, and you particularly like researching conspiracy theories, and drawing analogies between various seemingly unrelated topics. Tell us whether you remember when it was that you decided to follow this path as an artist; was it a specific work of art, a figure or an interesting story that inspired you to make certain things up?

Jakub Woynarowski: I do not think I can recall the exact moment when I started to be interested in such motives. Since the very beginning my approach to aesthetics or, generally speaking, to the entire visual culture, was pluralist and eclectic. When I was a child, we had albums with ancient paintings and the Projekt magazine on our bookshelves at home. The magazine featured designers and conceptual artists, and I also drew inspiration from comic books, scientific books full of graphs and charts, as well as from music scores. Incidentally, music has been a particularly close form of artistic expression for me. I was allured by abstract notation and non-verbal, sensual expression, which reveals its full potential when a musician is improvising. Drawing is similar. I often resort to it when I create works based on a rigid structure with clear conceptual references and I want to fill them with organic tissue born out of sheer instinct. It is a kind of biological freestyle within a solid frame, just like in the French formal garden. I like combining opposites. That has always been a natural tendency for me.

For that reason, when I was a student I was annoyed at the approach to art history resembling a binary numeral system. On one hand we have the proponents of traditional art who constantly quote the Platonic triad of “good, beauty and truth”. They stand in clear opposition to the “degenerated” art of the 20th century. On the other hand there are modern followers who keep their distance from dusty archives and who emphasize that art developed its full potential only after the avant-garde revolution, which allowed for an uninhibited explosion of creativity. Interestingly enough, despite these extreme differences in their approach to art, both groups managed to find a consensus on the issue of the avant-garde movement as unquestionable turning point in the art history. I was never able to accept this binary opposition. This is probably where my artistic and research project entitled Novus Ordo Seclorum came from. I have been working on this project for over a decade. My goal is to present the inconspicuous network of references between the traditional and avant-garde art. Some people may think that what I just said is a cliché, since we all know that in the history of art nothing came out ex nihilo. But what will happen if we question the concept of “developing” art? Can we compare art to advancements in technology where new models replace the old ones? Is the history of art constantly revolving in circles? Are we under a delusion of progress taking place in increasingly shorter periods of time? Something new and fresh can easily replace what is old and exploited but surely we can notice similar patterns on a larger scale, when we analyze art history. Think about revolution. Isn’t the meaning of the word fully consistent with its etymology? Isn’t revolution simply about turning around?

Jakub Woynarowski, „Veraicon (I)”, acrylic on canvas, 2016

Marta Kudelska: Some people think that the turning point in the development of avant-garde art were abstract works.

Jakub Woynarowski: It is worth asking ourselves whether the abstract-conceptual revolution was as rapid as it is now considered and whether a sudden breakthrough is just another myth propagated by avant-garde artists themselves. Modern art, particularly contemporary art, puts an emphasis on the concept of originality, which is strictly connected with the question of authorship and related legal restrictions. Maybe this post-renaissance formula is becoming obsolete and we are witnesses to this process? Some people may have the impression that contemporary art is receding and transforming itself back into the medieval model. In the Middle Ages, artistic “branding” was much less important than repeatable, but constantly evolving, memetic structures. This assumption does not resemble the idea of a romantic genius who lives all alone in the dark and is the architect of the fortune of mankind. Some avant-garde artists went along with this ethos more or less intentionally. This created many contradictions, for example the Bauhaus manifesto, which conspicuously asked for the abandonment of individual ambition and recreating guild-like structures which existed in the Middle Ages. Obviously, today’s artworks market dwells on romantic mythology, therefore art lovers obsessively search for “new names” and works “straight from the workshop”. Rational business strategies are sometimes a mere cover for conservative thinking. Of course, the true conservatism would be following the medieval way of thinking (laughs).

Marta Kudelska: In your opinion, what are the origins of what we today call contemporary art?

Jakub Woynarowski: Let’s come back to non-figurative art. If we forget about the modernist mythology, we have to realise that abstract language has been present in art for a really long time. What I have in mind are not the obvious examples of decorative arts. Abstract art has a really long tradition. Abstract works equaled conceptual works created to visualize transcendental or incomprehensible phenomena. In esoteric systems, non-figurative art has long been one of the basic means of visualization. Hilma af Klint is one of the figures on the brink of both worlds. She is considered one of the founders of the 20th century avant-garde. Piet Mondrian, a member of the Dutch Theosophical Society, also drew his inspiration from similar sources. Kazimir Malevich was another person interested in theosophy.

Jakub Woynarowski, Aneta Rostkowska, ”The Strange and Terrible Saga of the Jindřich Chalupecký Award”, lecture-performance, Národní Galerie, Prague, 2017

Marta Kudelska: We have smoothly transitioned to another important element of the puzzle; the Black Square by Malevich.

Jakub Woynarowski: The Black Square by Kazimir Malevich is an iconic painting for the Grand Avant-Garde. We can treat this work as an apophatic and conceptual illustration of an undefined kind of spirituality, a reality from outside of this world. Malevich’s picture attracts the attention of the audience not only thanks to its form, but also because of the fact that it presents a certain vision of the world. Not many people know that a similar black square was created 300 years before Malevich presented his own work. In 1617, Robert Fludd, an English scientist, presented his own visualization of a primordial chaos which accumulates the infinite potential of all pictures on one surface. His vision assumed the form of a black square. Fludd’s square had the same description on all sides, which said: “And so on into infinity”. Malevich’s intentions were similar. He called the black square “an embryo of all possibilities”. We should not forget that Malevich kept many secrets about his work to create a sacred ambience around it. When he described the creative process which led to the creation of this work, he described mystic experiences. The manner in which the work was first presented also related to sacrum and temples, since the convention of presentation resembled icons. The author identified with his work to such an extent that when he designed his own coffin he placed a black square where his face would be. He treated it as an iconoclastic coffin portrait. Malevich’s funeral was, in fact, a precisely designed ‘happening’. The “icon” became a universal symbol and it was put on a truck and a train which carried the coffin. It was also placed on the artist’s grave, in the shadow of a large tree. The myth of the black square was not born solely because of the artist himself, but also thanks to creative interpreters and average persons, who treated the work just as we treat catchy memes today. Interestingly enough, Malevich’s picture is considered a symbol of modernity. On the other hand, it goes way beyond what is modern, for example, by making references to medieval icons whose authors were not considered important and whose genius creators were surpassed by cosmic, supernatural elements. Now, we should ask ourselves if Malevich assumed more of an avant-garde approach or remained conservative with respect to his original concepts. Undoubtedly, he drew inspirations from the Russian art tradition before westernization, i.e. the processes initiated by the reforms of Peter the Great and Catherine II, just as many other artists of those times did (one example of such artist is the icon painter Vladimir Tatlin). On the eve of the outbreak of revolution which coincided with “Orthodox enlightenment”, the language of iconography, featuring primary geometry and pure colours, outweighed the mimesis advocated by the Saint Petersburg school. This combination of communism and medieval traditions can be really confusing. The black square created by Malevich perfectly depicts these contradictory tendencies.

Jakub Woynarowski, „Spectrum”, digital print, 2017

Marta Kudelska: You like browsing and searching for things that are somewhere in the peripheries of the history of art. You are aware that, in fact, they belong at the center but were pushed aside for certain reasons. A perfect example here is Incoherent Arts, which totally changed our perception of the revolution that was supposed to happen thanks to avant-garde and modern art.

Jakub Woynarowski: When you analyze Incoherent Arts you realize that, apart from the opposition to conservatism, there is another significant issue that defines the identity of the 20th century avant-garde: the sense of humour and the juxtaposition of the exclusive and the egalitarian. The Incoherents, which was the short-lived French movement from the 19th century, can be regarded as an excess. At the time, it was extensively covered in the media, and we can call the Incoherents celebrities, especially taking into account the opinion published in one of the newspapers of that time, where the authors claimed that 20th century art will either be incoherent or it will cease to exist. When we look at the formal aspects of work by the Incoherents, their activity is strikingly similar to what the Dadaism and Fluxus art movements produced. On the other hand, when we look at the origins of incoherent art, we immediately see a reference to the so-called caricature salons – casual jokes related to academic traditions, which were first published in newspapers and, later on, adapted to be exhibited within the “anti-salon”.

The core of this incoherent art movement was not only formed by visual artists, but also by journalists, illustrators, cabaret artists and writers. It is important to note that the Incoherents emphasized their opposition to academics, but they also distanced themselves from new revolutionary doctrines, such as impressionism, which was supposed to be a stepping stone in the development of the future avant-garde. “Incoherence” was aimed at being the third path and did not allow itself to be easily categorized and placed at any side of the binary opposition between the old and the new. Jules Lévy, the founder of this movement once said that “seriousness makes you stupid, while cheerfulness enlivens you”. Although the Incoherents did not create any manifestos, the statement I just quoted distinctively defines the artistic strategy of the movement. Unfortunately, the Incoherents are denied their place in the history of art and they are popularly regarded as a “cabaret”. Obviously, this cabaret has nothing to do with Cabaret Voltaire. When we look at the movement in this way it is easy for us to disregard the fact that “incoherent” works encompassed everything truly avant-garde – abstract painting, minimalism, conceptualism, readymades, happenings…

„Mad Tea Party” (curated by Aneta Rostkowska and Jakub Woynarowski), „Fugitive Mirror” by Alexander Nagel and Amelia Saul, lecture/video, Christuskirche, Cologne, 2017

Marta Kudelska: And these are things which are characteristic of contemporary art.

Jakub Woynarowski: Exactly. Incoherent arts pointed to the future. The activity of incoherent artists was provocative, but was never regarded with disdain. It was just the opposite – the Incoherents became very popular. This popularity was achieved thanks to their approach to realized projects. They did not want to be regarded as iconoclasts. Their activities represented “socially engaged art” and the money earned during the exhibitions was always spent on charity. The art of the Incoherents was undoubtedly inclusive. Its underlying principles were interaction with the audience and acting outside of the formal institutions, for instance in private houses. Their first exhibition, organized in 1882, was in a small apartment and was really popular among the general public. Ludwig II of Bavaria and Wagner were among visitors. Incoherent artists also undermined the traditional exhibitions organized in art galleries. For example, they invited visitors for the opening night of their exhibition which, in fact, was not even finished. During this opening night they were covering their works with varnish. They liked acting in a public space. A perfect example of an incoherent artist acting in a public space is Sapeck – who walked along the streets of Paris with his body painted in blue. Sapeck is the author of one of the most iconic works for which Incoherent arts are known; The Joconde smoking pipe, and it is strikingly similar to the painting created by Duchamp thirty years later!

When we look at this explosion of creativity lasting for more than a decade, we get the sense that humour is an important aspect in the early history of avant-garde art (which, however, was normally considered as truly serious and even ominous). We can refer this to the medieval carnival which functioned as an enclave and was not covered with official jurisdiction. It allowed for profanation of holiness under excuse of just having fun (I would like to mention here holy masses celebrated by animals or flash mobs where participants throw food at each other). I also understand the reference to the situation of a contemporary artist who acts in a protected territory and is, therefore, free in his activities but limited in his causative powers. Nevertheless, I have the impression that today we are living in much calmer and rational surroundings and the time we live in is rather stable in comparison with the wild Middle Ages (laughs).

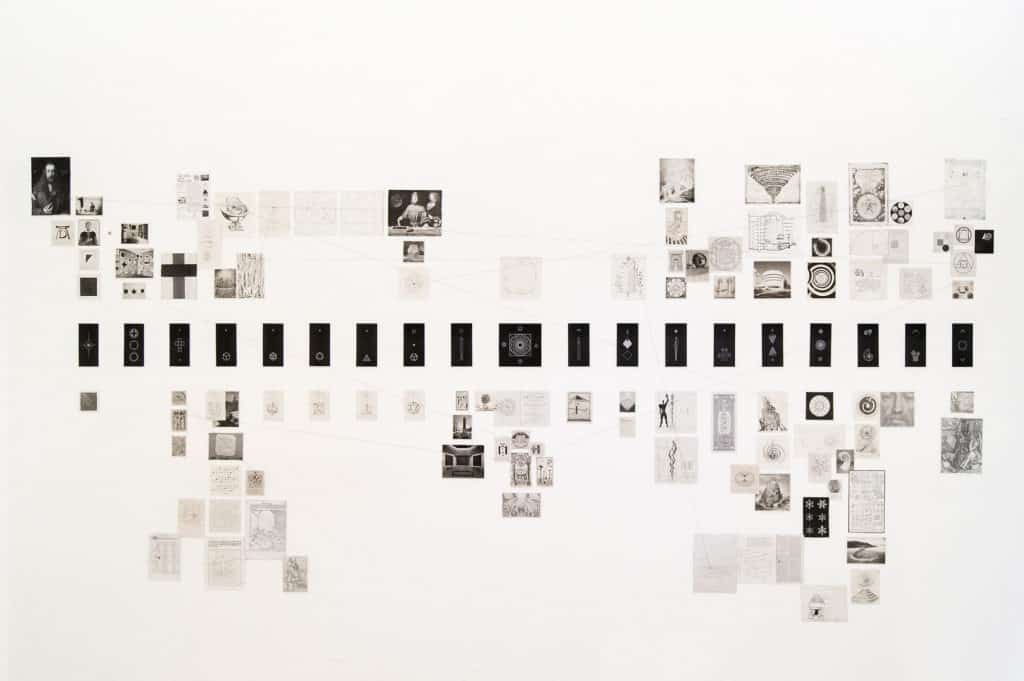

Jakub Woynarowski, „Characteristica Universalis”, installation view, Palazzo Ruspoli / Fondazione Memmo, Rome, 2017, photo: Jakub Woynarowski

Marta Kudelska: That takes us all the way back to the modern era. What are you working on now?

Jakub Woynarowski: After the conversation we just had, I have to mention the recently opened exhibition entitled Conversation Piece | Part IV – Giant steps are what you take organised at Fondazione Memmo. This project symbolically sums up six months of my activity at various galleries in Rome, at the Fondazione Pastificio Cerere and the Z2O Sara Zanin Gallery. The exhibition, which also features works by Yto Barrada, Eric Baudelaire, Rossella Biscotti, Jörg Herold and Christoph Keller, focusses on the topic of a private path in the art world seen as a creative procedure similar to alchemy. My path is an alternative narration of the history of art. I present this narration in the form of a monumental installation on the facade of Palazzo Ruspoli. The installation is complemented by the “visual atlas” which can be seen at the gallery and is a kind of non-verbal auto-commentary. This project is obviously just a single building block for my magnum opus, which is a paranoiac conspiracy theory regarding the history of art. I intend to present it to my audience in the form of a book and a feature film. I hope that is what the future will bring.

Jakub Woynarowski, „Characteristica Universalis. Picture Atlas”, installation view, Fondazione Memmo, Rome, 2017, photo: Jakub Woynarowski

Special thanks to Katarzyna Nalezińska

Jakub Woynarowski, „Characteristica Universalis”, installation view, Palazzo Ruspoli / Fondazione Memmo, Rome, 2017, photo: Jakub Woynarowski