First an artist’s face appears on a screen. I can see she’s in a gallery space – white walls are visible behind her with paintings hanging on them. The artist talks to the camera, checks the sound quality, asks if we can hear her. She says we have to wait for more people to come. After a few minutes she starts talking about her work. In an empty white cube. Alone with her work. And the camera. It sounds like another virtual art work, an online performance. It is, however, the opening of Paulina Pankiewicz’s Being Paul Cezanne exhibition in Zachęta’s Project Room. A man peeks into the gallery and starts staring into the empty room and the artist talking to the screen. Is he worried? He could think the lady is disturbed – sitting in an empty gallery and talking to a screen. Perhaps he then begins to wonder who she’s showing the gallery to. Or maybe he decides she’s recording a video, since, after a while, he walks away.

A performance, then. There is something amusing in this picture: How can events which for two hundred years have been gathering large groups of people take place in an empty space with only an artist and her work?

Usually an exhibition is the culmination of the creative process. It allows the artist to see her work outside the studio, in a new space, in a new context. The exhibition is also an opportunity to confront her audience, their reception: their criticism, affirmation or (most often) indifference. The exhibition fuels the art market, it allows the artist to sell her work and make ends meet. Even so, I don’t know if I can agree with Karol Sienkiewicz that the exhibition is the basic medium of art. These last few months have changed the way we think about art’s life cycle.

Overheard Conversations

During the lockdown I overheard a discussion two men were having in the underground. I really overheard it. I’m not making this up. We were traveling from Pole Mokotowskie station to Ratusz Arsenał station in Warsaw, so I had a fair amount of time to spend in the company of their thoughts. The discussion centred around the closure of galleries and how the men were trying to cope with art online. They talked about the various virtual productions of different galleries, some more successful, others less. They soon began to reflect on the importance of the physical aspect of a work of art (really, I’m not kidding). At one point, one of them said, “I never thought about these issues before. In the past, the mere experience of a painting or an exhibition was enough for me”. I wanted to reply: „You know full well that now this experience has lost its power. The best you can do is pretend it hasn’t”. But I did not dare to speak. Politely, in silence, I waited for my station and left the carriage, my mind far from the gap beneath me.

A Rough Night at the Museum

Muzeum Sztuki in Łódź organized a virtual visit to its Neoplastic Room as part of the Long Night of the Museums. I decided to take part in it, believing it would be a good idea to remind myself of all those abstract paintings I used to study so carefully.

Exactly at eight I was ready to start my tour. At first, it turned out that the app wouldn’t work on my browser. Fine, I downloaded a different one. Then the website would not load. I tried to connect with it several times. Finally, the Neoplastic Room appeared before my eyes. Unfortunately, the cursor would not work and I had to refresh the page again, which resulted in me having to load the page, and again (because the previous had jammed), and again (this time because of my impatience). After twenty-five minutes of battle, I could finally see Katarzyna Kobro’s Abstract Composition from 1924. A blue continuous form on a white background. Blue contains white, white contains blue. Round shapes in one place, related to the sharp ends of the figure in another. Objectively it’s an interesting use of the canvas space. However, when I looked at the painting, I felt nothing. Neither curiosity nor disapproval. I was looking at a work of art, I was perceiving it visually. If I had been there, in the museum, my eyes wouldn’t have worked differently, I wouldn’t have seen another work of art, right? But I knew I wasn’t experiencing the artwork.

This was because visual arts are not only visual. I would call them sensual arts. Experiencing them should take place with the engagement of several senses simultaneously, otherwise the aesthetic feeling is not complete. The whole event – leaving the house, going to the exhibition, leaving the coat in the cloakroom, then looking at the work of art in a given space, with other works of art around it, with other people around us – is the process of experiencing art. When all these activities, in their various configurations, are completed, we can speak of intimate involvement.

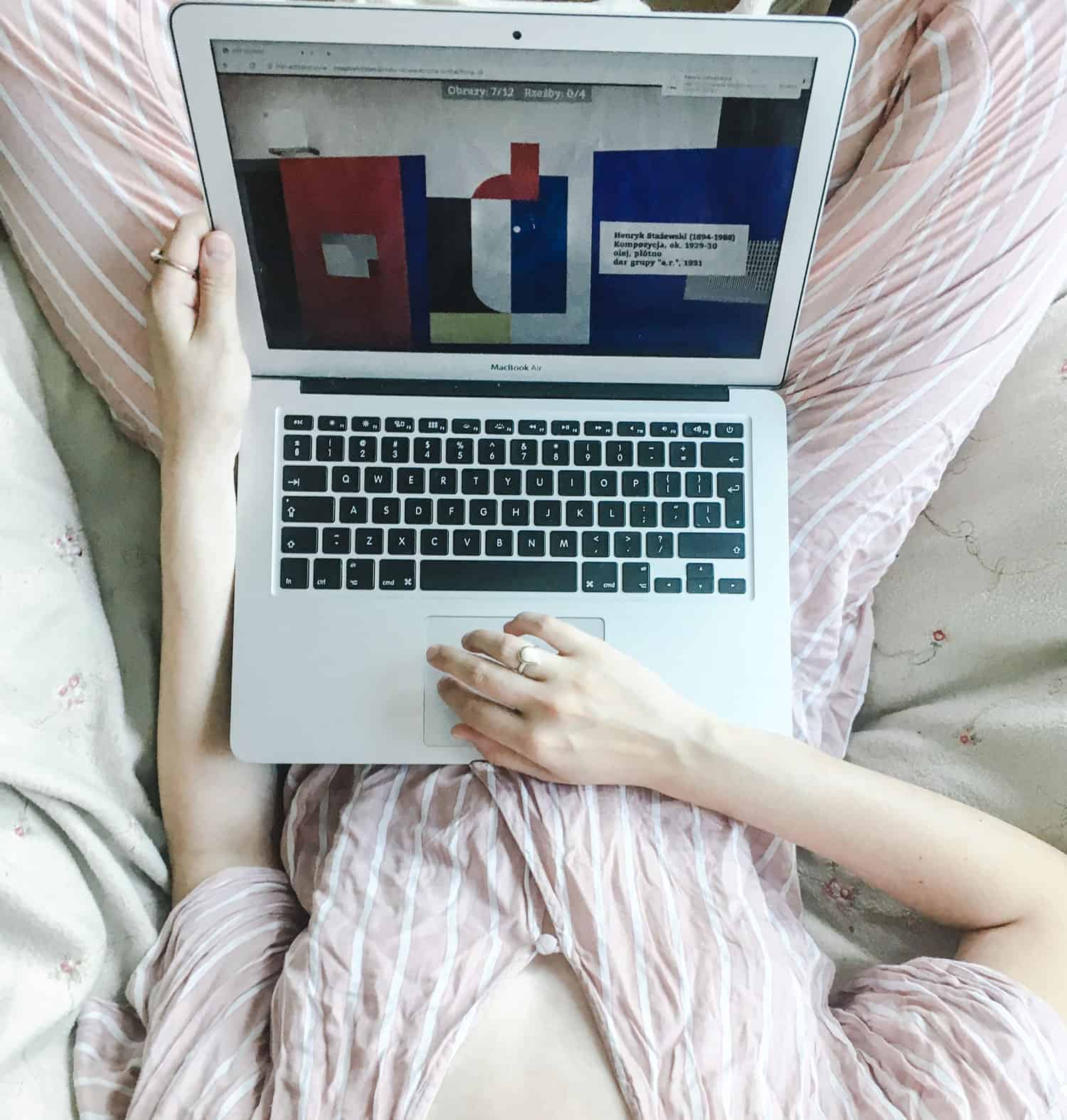

Is Art Better in the Bedroom?

There are some visual arts media that are only visual and in their case it makes little difference whether I watch them at home, in bed, or at an exhibition. Video art, for example. Ever since the Museum of Modern Art in Warsaw started regularly releasing art films online, I’ve begun to engage with this form of art more often. As I write this, the last MSN Cinema screening is taking place. My viewings have become a sort of ritual over the last few weeks: preparing tea, shutting myself in my room, away from the noise of the house, curling up in a comfortable position in bed… a completely different experience than in a gallery. Before, for example at the Zachęta exhibition Videotapes. Early Video Art, I felt overwhelmed by the enormous number of movies to see. It also seems to me that the museum space doesn’t encourage watching videos. Usually you either have to stand with headphones over your ears, or the benches are extremely uncomfortable, or the videos are inordinately long. It is completely different at home. Even a video lasting an hour or more can be watched without too much trouble. The aesthetic experience is then much more complete than seeing the same material in a museum. On the other hand, isn’t it the case that when you watch a video online at home, the work of art loses its status as art? How does it then differ from the next episode of the series you’re watching or the video you saw on YouTube? Is the only difference that it’s published on a museum’s domain?

So how is it? Are some exhibitions important, others less? Some works of art must remain in physical form. Others, thanks to the medium they use, can do well in virtual spaces. Especially new media art, which we are seeing more and more of every year. Does this mean that we could permanently transfer certain artistic activities to the Internet? Have the solutions adopted by many museums during the pandemic proved to us that some of these activities no longer count?

Written by Anna Świtaj