Krystian Grzywacz is a young multimedia artist who relishes in experimentation with new media, movement design and media clash. He typically works with video, animation, VR and sculpture. Our editors were captivated by his piece Still Life, unveiled as part of the Best Media Arts Graduation Projects Competition held in Wrocław. Interestingly, it all started by accident. In our interview, the artist reveals how it all began, discusses his sources of inspiration and gives us a sneak peek into his upcoming projects.

Krystian Grzywacz, photo by Olga Markowska

Anna Dziuba: Let’s start at the beginning – why did you choose new media art as your medium and what aspects of it do you find most compelling?

Krystian Grzywacz: It started out of nowhere, randomly. While I’d been preparing for entrance exams for a graphic arts major for two years before I enrolled in an academy, I realized almost instantly that I felt most comfortable synthetizing my thoughts and responding to problems through a visual format. Still, the gate to the department was bolted shut, it turned out my grip on the brush just wasn’t strong enough. After I saw my name at the bottom of the list of rejected candidates, I started exploring other alternatives. Luckily for me, the enrollment procedures for the intermedia department were still ongoing. The next year, I applied for graphic arts once again and kind of failed miserably. On top of that, I was almost run over by a garbage truck right after the exams, so I took it as the ultimate sign that I should pursue my current studies rather than chase after my initial plan. The tables turned after I opened my heart to the myriad of tools offered by the contemporary art market. I fell in love with movement design, media clash and experimentation with some newart forms. I adored upending my vectorial progress, honing an artistic craft by way of destructive and random activities in lieu of conventional development.

A.D.: Where does your inspiration come from? How do you come up with your ideas?

K.G.: Usually I look to my dreams for inspiration. It’s the never-ending struggle between pathological procrastination and hyperproductivity. During bouts of intense work, I sometimes tell myself that, apart from its obvious benefits, sleep can bring me the solution to my creative problem. Even though this antidote is far from perfection, my selective memory of the times when it helped me has allowed me to persist in it to this day. Seemingly pointless, absurd and stupid coincidence is an excellent stimulus. I try to take life as it is because as they say, life writes the best scenarios.

Krystian Grzywacz – Still LifeEugeniusz Geppert Academy of Art and Design in WroclawFaculty of Graphic Arts and Media ArtStudio of Narrative and Interaction in New MediaSupervisor: Maja Wolińska, Ph.D. DSc

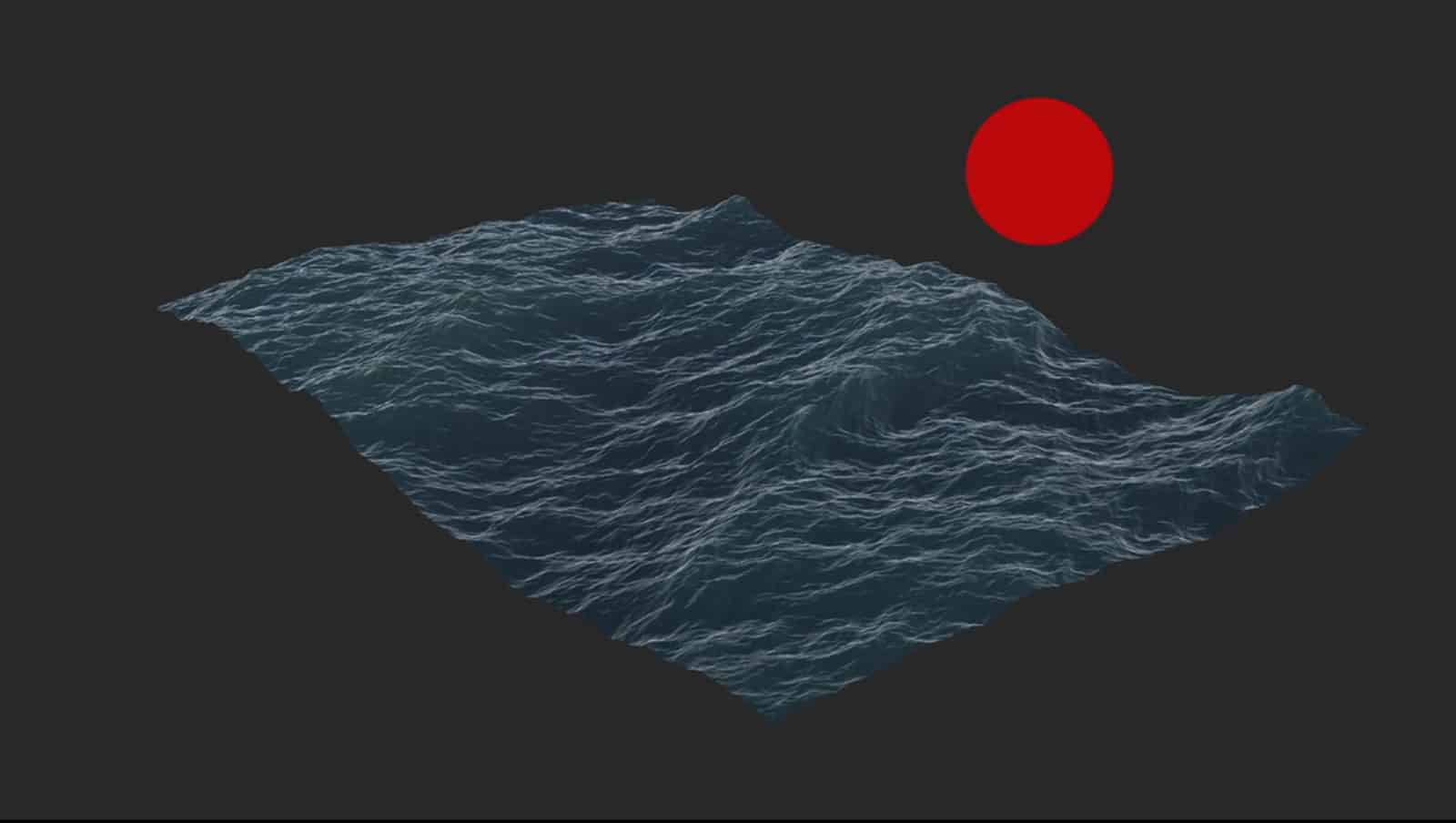

Krystian Grzywacz, Sill Life, 2019.

Krystian Grzywacz, Sill Life, 2019.

A.D: What’s the main subject of your work titled Still Life? Was your intention to comment on the development of artificial intelligence systems or the condition of modern humanity? Could you please tell us something more about the piece?

K.G.: I found the Simulation Argument posited by Nick Bostrom incredibly inspiring while shooting the video. The argument states that at least one of the following propositions must be true:

-

- No civilization will ever reach the level of technological advancement indispensable for simulating reality;

- No civilization that would reach such a level is interested in running multiple simulations of reality;

- All people with our kind of experiences are almost certainly living in a simulation.

Not only lots of science-fiction works, but also predictions of expert scholars and futurologists suggest that an enormous computing power will be available in the future. There’s a high probability that one of the operations performed on a supercomputer will be running an incredibly detailed simulation of one’s ancestors or people alike, like a billionth edition of the Sims. One might safely assume that a machine with such computing potential, in addition to obtained knowledge, would allow one to simulate the consciousness of individuals. If these predictions do come true, then there will be no reason why one shouldn’t run multiple simulations of this kind or even why the subjects immersed in the simulated reality shouldn’t run these simulations themselves. Following this hypothesis, the singular original reality, where it had all started, will be dominated by the higher incidence of potential simulations of reality. From this perspective, the probability that we the people living on the earth are subject to such a simulation is relatively high.

The foundation of this hypothesis is the concept of substrate independence, meaning the autonomy of the base surface. This notion was coined with the view of making people realize that the human mind and its possibilities are so flexible and dynamic that it is completely separate from any fixed set of atoms. The best example would be the fact that the human organism substitutes these atoms on its own. Furthermore, one could draw a conjecture that, assuming all the essential functioning requirements are met, the consciousness could be implemented into the silicon-based processor inside of a supercomputer instead of the carbon-based biological neural networks of the brain. This controversial assumption doesn’t have to be true, however. After all, there is a possibility of generating a computer-based consciousness analogous to the human mind and yet operating within a completely different architectural framework. Computing power required for creating the fictional humanity is dependent primarily on its precision. Running a rich simulation of the entire world is, to put it simply, a tough nut to crack – but it’s not the final answer for making the attempt at realistically replicating the human experience and environment devoid of any serious empirical proof confirming that it’s just a simulation. The system used currently in video game production to boost efficiency might as well be adopted. This system is based on limiting an amount of things within a gamer’s field of vision, which means that the amount of mediums required to replicate the full illusory experience of being in the environment while maintaining cognitive limitations might be diminished by a lot. What is more, the driving force of a producer of such simulations allows them to revert the simulation easily to adjust the parameters properly or run it again from the beginning. I highly recommend Nick Bostrom’s book “Superintelligence: Paths, Dangers, Strategies” to readers who are interested in this subject.

My graduation project Still Life, underpinned by this hypothesis, is the snapshot of technological evolution set in motion. Its narrative is comprised of the collection of the simulated profundity and quasi-sensuality of the GPT-2 model (AI system) producing text on the basis of source material while preserving its original style and subject. This model was created by the OpenAI research group in late 2015. The project’s founders include Elon Musk, Sam Altman, Ilya Sutskever and Greg Brockman. Currently, some of the world’s leading experts in artificial intelligence are working on this project. Based in San Francisco, the organization is open to collaboration that aims to create a controlled environment for AI development. As opposed to its predecessors at OpenAI, initially the GPT-2 system wasn’t available to the public due to the concerns about its potential misuse, such as automatic dissemination of fake news on a massive scale. After a while however, the scientists agreed to release the medium version called 345M (the name comes from 345 000 000 parameters applied to predict the words of generated text) to test it among the interested programmers and linguists. Paradoxically, the fact that the content produced by GPT-2 contains language mistakes makes it even more human since making mistakes is part of our nature.

I’m glad I stumbled upon the early stages in the system’s development. Soon the fruits of its labor would be indistinguishable from the content generated by people, which is astonishing on so many levels and yet is slightly disheartening. The glitches appearing alongside surprising amalgamations of meanings and associations give rise to the poetics of the absurd and hence ambiguous interpretation. As I designed the animations accompanying generated words, I tried to create tension while still leaving some space to breath and avoiding an overtly direct correlation with the displayed text. The result is a film to be read rather than watched.

Krystian Grzywacz, Vacant Spaces, 2016.

A.D.: What is it like to work with the Artificial Intelligence? Did the end result catch you by surprise?

K.G.: Working in the uncanny valley is extremely stimulating. Essentially all of my experiences with various AI models have brought surprises, smiles, horror and absurdity. Oddly enough, numerous functions of the systems are rooted in the visual sphere, while the graphics cards are the main calculating units. This fact opens a broad spectrum of possibilities for contemporary artists hiding behind computer screens. Surely, some programmes are rip-offs. In order to elevate their marketing strategy, some programmes based on conventional logical structures are presented in a way suggesting they apply the AI module. I almost fell prey to such a hoax. As I was working on Still Nature, I came across an online poetry generator. If it wasn’t for dr hab. Maja Wolińska (my supervisor) encouraging me to check the code, I would’ve gone with it. Nonetheless, all of my doubts were dispelled when I saw GPT-2. I was certain it was an advanced tool that I wanted to work with. Soon after the release of the medium version, GPT-3 saw the light of day. The progress was staggering. Online you can find an enlightening interview with the human avatar generated on the basis of text (“What It’s Like To be a Computer: An Interview with GPT-3”).

A.D.: Do you observe viewers’ response to your works to gauge their reactions?

K.G.: My films were screened at various festivals and group shows, but usually in the dark. Besides, I wasn’t there since I saw them already. So no, I didn’t have much of an opportunity to observe audiences’ reactions in real time, though I’m always attuned to the comments. Even the initial confrontation, regardless of whether the response is positive or negative, makes the time and energy I spent creating the piece simply worth it. I’m not the kind of person who hides my USB drives in a drawer. In my mind, what I do is meaningful even if my work only resonates with one out of dozens or hundreds of the people who interact with it.

Krystian Grzywacz, Sandal, 2019.

Krystian Grzywacz, Sandal, 2019.

A.D.: What project are you working on right now? Is there any particular subject you wish to address?

K.G.: I’m working on several projects, actually. Some of them are top-secret even though they weren’t commissioned by the CIA. I can tell you about the others, for instance a music video for this Tricity-based band called Aleph. Their new upcoming release announced by this single might just be one of the greatest albums in the history of humankind. The song has an immense depth to it. I’m facing the challenge to rise to their level when it comes to the visuals accompanying their composition, into which they clearly put so much effort. In addition, I’m gearing up to shoot my own medium-length film debut. The subject I intend to explore is the modern approach to the motif of dance macabre. Right now, I’m at the very early stages of pre-production, but reality is rife with research materials.

A.D.: Well then, fingers crossed. Thank you for the conversation.

Krystian Grzywacz, Bastarda Pax Esterna, 2018