Barbara Piwowarska, photo: Bownik

Alex Urso: Let’s start with the project, which you curated within the space of the Polish Pavilion at the 57th Venice Biennale. What is about Little Review?

Barbara Piwowarska: Little Review is an ongoing project by Sharon Lockhart that runs both at the Polish Pavilion in Venice and in Poland. It was created with young Polish women, group of over 30 teenagers from the Youth Sociotherapy Center in Rudzienko, an institution near Warsaw that Sharon collaborates since years. The eponymous Little Review (Mały Przegląd) was an unprecedented newspaper established by Janusz Korczak, written by children and teenagers and published as a weekly supplement to the Jewish daily Our Review (Nasz Przegląd) between 1926–1939. Korczak was a famous pre-war avant-garde writer, progressive educator and orphanage-director. The project refers directly to his theory and practice “of giving the voice to children”.

Similar to Korczak, Lockhart’s goal was to provide a forum for children’s voices – both past and present. The exhibition in the Pavilion resulted from extensive workshops in Rudzienko and Warsaw. It comprises Lockhart’s new film, series of photographs, and first ever English translations of the archival issues of the Little Review newspapers – chosen by the girls. The Little Review is a tool and metaphor here, translated into contemporary media and context. It challenges stereotypical image of teenagers from youth socio-therapy centers and changes their own view of how they can be perceived by the society. It is a collective portrait of adolescence. It captures the moment when girls become adult women.

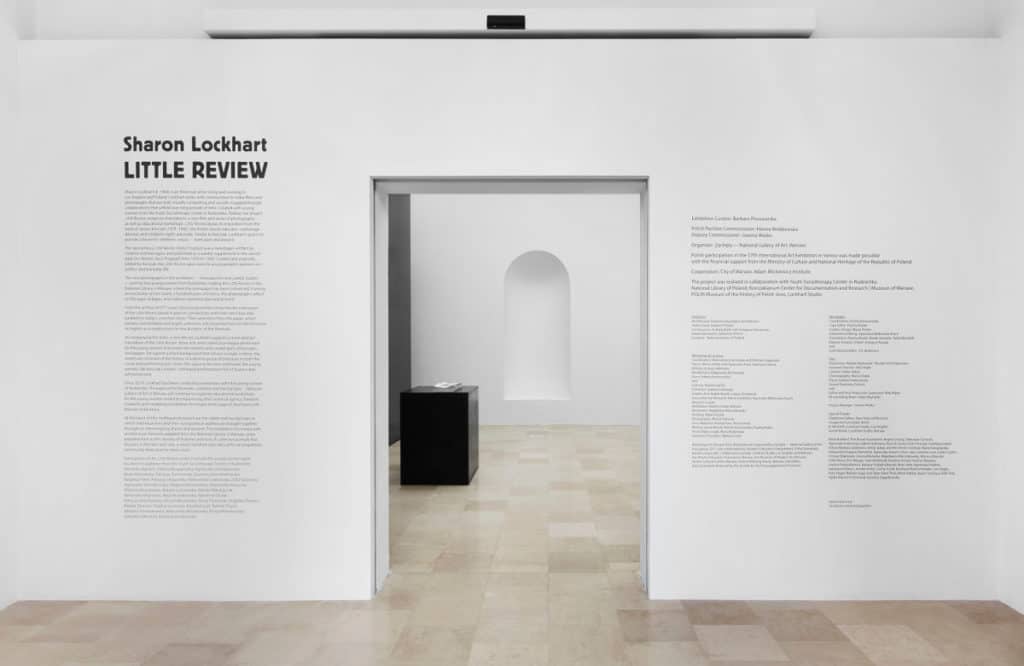

Sharon Lockhart, Little Review, Polish Pavilion, 57. Venice Biennial, 2017, exhibition view, photo: Jens Ziehe

A.U.: The exhibited photographs portray young women from the Youth Sociotherapy Center in Rudzienko, reading copies of Little Review in the National Library in Warsaw, where the newspaper has been conserved. There is indeed a clear intention to encourage a dialogue between past and present, across nearly a hundred years of history. In what way does the project explore Poland today?

B.P.: It gives attention to those unheard and invisible: very young Polish women from smaller cities and villages, but also to youth sociotherapy centers that are minor and little known sector of re-socialization and educational system in Poland. They will possibly change because of new governmental educational reforms that already started.

Lockhart convinced group of her 32 young collaborators to read, to face the content of a 90-year-old archival newspapers, and to learn about the stories and problems of their peers – pre-war correspondents of the Little Review. She believed they can do it. Nobody would. Sociotherapy centers in Poland are perceived as those that are hosts for “troubled girls” (this is the term mostly hated by Sharon), and especially those that “don’t like school, reading or learning”. Lockhart wanted to divert this cliché. Girls had to go through 677 issues of the newspaper stored at the National Library, learn how to use directories, reference symbols, and to note that the last issue of the Little Review was published on Friday, 1 September 1939, on the day of the outbreak of the WW II. For a few months they created an “editorial team” whose task was to identify the 29 issues that were the most relevant to them – in connection with their life experiences and current problems faced by teenagers. We’ve all learned that these problems didn’t change at all. They are the same.

In the vestibule of the Pavilion, a stopped broken clock is hanging, along with the three displayed benches from the National Library. For us that huge library clock has a symbolic function: it reminds of the time loop, of the nearly hundred-year-old community – that the project and exhibition are part of. It points to the “gap” between today’s generation and their pre-war Little Review peers, and to stories that have never been told. Large-format photographs show the girls reading the Little Review newspapers on the same benches that are in the exhibition space. Agnieszka reads an issue with the futuristic “Manifesto of the Milky Night”, written in 1935 by Ryszard. Ola leans over the article “As the Heart Spreads Joy”, from June 1939. Another photograph shows her meaningful glance directed at the audience (she looks here like a young boy) – she becomes a manifesto. The title of this work Today in Politics refers to the article “Political Day” from 1939. The exhibition not only gives voice to young Polish women, but also to the pre-war generation of young people who are no longer here. Girls became aware of what they took part in for Venice. They visited Pavilion and Biennale in June. We just presented the project together with Ola and other girls during The 3rd International Congress of Children’s Rights / The 8th International Korczak Conference at POLIN Museum. They were official conference participants and commented on their experiences within the Pavilion process.

Sharon Lockhart, Little Review, Polish Pavilion, 57. Venice Biennial, 2017, exhibition view, photo: Bartosz Górka

A.U.: Your relation with Sharon Lockhart dates back to years ago, at the time of your stay in America. How did your collaboration has begun, and what motivated you to explore her practice?

B.P.: We’ve met with Sharon 10 years ago in New York and in Berlin, after I organized her first Polish screening in Silesia in Bytom during international residency Live, Survive and Create! organized by Sebastian Cichocki in Galeria Kronika in 2007.

At that time I worked a lot with experimental film and video. I was fascinated by her analogue films on 16 mm tape, and especially how they expanded filmic and photographic medium, how she conceptualized them. Lockhart plays with the real and the staged. Her films are slow, static – reminiscent of painting, theater, photography. In turn, her photos are reminiscent of filmmaking, scenes sequences. She stretches the time, expands the time-space. Structurally, her practice can be compared to James Benning, Andy Warhol or Michael Snow. Sharon derives from traditions of the 60s and 70s. As she admits, she was also inspired by Morgan Fisher, Chantal Ackerman, Yvonne Rainer. It is how I started to follow her work, just before I started to work with Łukasz Ronduda at Film Form Archive at CCA Ujazdowski Castle in Warsaw.

In 2009 Adam Budak brought Sharon to Łódź, where she made her film Podwórka as part of the Anabasis exhibition. Four years later he organized her individual exhibition Milena, Milena at CCA in Warsaw, which was later presented at Kunstmuseum Luzern by Fanni Fetzer, who in 2007 was also participant of the residence at Kronika in Bytom. It all resulted with one of the most interesting publications on Lockhart’s work, introducing for the first time the phenomenon of the Little Review newspaper, which also included extremely inspiring Lars Bang Larsen’s text Childhood’s End or: The Child’s Integration in the Society without Qualities on Lockhart and Korczak, referencing Arthur C. Clarke.

Sharon Lockhart Ola, “TODAY IN POLITICS,” Our Review no. 167 (8863), June 16, 1939, National Library of Poland, Warsaw, February 3, 2017

Sharon Lockhart Agnieszka, “MANIFESTO OF THE MILKY NIGHT,” Little Review no. 131 (4568), May 10, 1935, National Library of Poland, Warsaw, February 2, 2017

A.U.: The choice of a non-Polish artist to represent the national pavilion has generated discussions and critiques in Poland (although it is not the first time that the Polish Pavilion proposes a foreign artist). In your opinion, how important is it to have the “identity” of a country expressed by a local artist in the national pavilion?

B.P.: Our project was chosen by the democratic jury consisting of many people from all around Poland, out of 50 entries sent by artists and curators from all over the world. It was an open international competition. But such critique never happen before, even with the trilogy by Yael Bartana presented at Polish Pavilion few years ago. Despite of the real wave of critique in Poland and strong ressentiment from both right and left wing of the Polish art world – in turn, huge part of the Warsaw art community joined Little Review project and contributed with extensive workshops for the Rudzienko girls. Over 100 collaborators joined Sharon and Pavilion team, and provided best what they could: choreographers, journalists, Korczak experts, scientists, visual artists, musicians, therapists, educators, curators, writers, and volunteers. Also other art institutions helped and organized educational programs for girls: POLIN Museum of the History of Polish Jews, Korczakianum / Museum of Warsaw, National Library in Warsaw, Museum of Modern Art in Warsaw, CCA Ujazdowski Castle, not to mention the Youth Sociotherapy Center in Rudzienko/Zielonka and the main organizer-producer of the Polish Pavilion: Zachęta – National Gallery of Art. For me it proved that we are beyond of such national distinctions. They all knew it is for Rudzienko girls and whole the project is still continued in Poland with series of workshops that will be held until 2018, or possibly longer. They were able to establish new inter-institutional “artistic” and “non-artistic” structures supporting the girls. The “identity” here are Polish young women. Lockhart is the one who was interested to collaborate with them, to hear their voice, and decided to devote her attention and time to work in Poland regularly, since over five years.

A.U.: Does it make sense to think that a pavilion, and therefore a single exhibition project, can enclose and express something about the cultural identity of a nation?

B.P.: Yes, I think it is possible, although we wanted to do something else. Little Review is not a single exhibition – it is a wider ongoing project between Poland and Venice. What you see at the Pavilion is only little part, sublimation of the extensive process held in Poland. It expresses the voice of young Polish women AD 2017 in a poetical and metaphorical way, and it also gives the voice to the pre-war generation of the Little Review newspaper young Jewish writers, who are no longer with us. This absence is an extremely important part our cultural identity. I think that Lockhart succeeded to create almost 100 years old community of the present editorial team of Rudzienko girls with the Little Review correspondents. Texts, problems, and fears of children and teenagers are very similar. They just have different tools and different media for expression. In this case the girls had also tool of performance and an experimental staged video. They invented some scenes wearing Justin Bieber t-shirt or Mickey Mouse clothes in a collective “gif”, picking up the worlds as their manifestos: love, trust, hate, hope – repeating them in a choreographed slow motion. Trust was in the center. They have chosen this “too long” duration, the “slow down” of gestures and meanings. In last scene of the film they are running with the sticks, choreographed by Sharon and great feminist choreographer and dancer Marta Ziółek. I guess it is a big challenge to agree, it is the most honest manifestation of young women power and contemporary identity of the female part of a nation. It was recently discussed in Polish right-wing newspaper that deeply disagreed with that Pavilion, with sexuality, with this “representation”.

Sharon Lockhart, Little Review, 2017, single-channel hd video installation, 27:17 min, film still

Sharon Lockhart, Little Review, 2017, single-channel hd video installation, 27:17 min, film still

A.U.: What does it mean, indeed, to “represent” a country? Considering the delicate political and social situation in Poland nowadays, do you find it a more prestigious or problematic task?

B.P.: Of course – both. I am an art historian and follower of the old avant-garde ideals and utopias, that aimed to go over, beyond the nationalisms, but I am also a realist. For me to “represent” my country – is to say something important. This Pavilion brings attention to young Polish women, teenagers, in 2017. This is what we wanted to do – to represent Poland with girls from Rudzienko socio-therapy center and to do Pavilion with them.

A.U.: Thinking about the Polish pavilions of the recent past, do you find a common line or substantial differences between your pavilion and those of the latest editions?

B.P.: Yes. We have prepared the application with Sharon in August 2016 bearing in mind we have to propose something that never happen before, and also something that looks different to other Polish pavilions (e.g. it never combined photographs, film and printed newspapers). I could only imagine Paweł Althamer instead of Sharon in the pavilion for this moment. I think he would do something special and similarly challenging (both formally and socially).

Polish Pavilion never had such socially engaged project devoted to young women or was never focused on historical archival material and Korczak legacy. We combined this two aspects and proposed something important to us, something we wanted to encounter, research, and reveal to international audience.

A.U.: You are often involved in curatorial projects that deal with topics strongly related to the social. Do you mean art as an opportunity for exchange and dialogue?

B.P.: Yes, of course. Especially after this project I do believe in “socially applied arts” more than before. I’m very grateful to Sharon and to Rudzienko girls I could be part of this endeavor. I think this project is efficient. I also encountered a real process for the first time in my life. Sharon challenges everybody. She has changed our views on teenagers in Poland. It was first time in my life I had to work with young girls, not kids any more, but still you can say: children. This is the biggest challenge for the art world and its future: the youth.

Sharon Lockhart, Little Review, Polish Pavilion, 57. Venice Biennial, 2017, exhibition view, photo: Jens Ziehe

A.U.: What were the main difficulties you encountered during the realization of the pavilion?

B.P.: The first challenge was to work with the teenagers. The second one was to produce the project within 4 months. It is really not enough time. Other countries conclude the competitions minimum a year before pavilions’ openings and have minimum 9 months for production. The third one were the pressures from many institutions involved. Such project for the pavilion has nothing to do with the curatorial experiences I had before. It was not at all a curatorial project, but something beyond your expectations or illusions. You had to forget the roles you are used to. It was a very good lesson – a real encounter with reality.

A.U.: What are the greatest satisfactions, at the end of the experience?

B.P.: The greatest of them was that Rudzienko girls visited Pavilion, Biennale, Venice and Lido. Nobody would ever believe it could happen. In most cases it was their first visit abroad and first such grand tour, accompanied by their teachers from socio-therapy center. They also met Sharon’s students there, Mark Bradford (the artist of US Pavilion) and his collaborators.

The second great satisfaction was to see 60 translated issues of the historical Little Review newspapers from 1926–1939. They were very little known phenomenon even in Poland, and never translated into any foreign language. These translations are important part of the Pavilion and now are available not only to the art word or visitors in print – they are to download online on Creative Commons license, free to everybody, students, scholars, universities. In between of whole the process, we got subsidies to translate more than 29 issues chosen by the girls and printed for the show. The other 30 were chosen by experts from Korczakianum, a center for research on Korczak legacy in Warsaw. We hope to translate more in upcoming months. And the last satisfaction is to see that the project develops in Poland, that it is ongoing with the workshops, and joined by so many great people from different fields. The girls are currently working on the new contemporary issue of the Little Review AD 2017 and on their own texts written on this occasion – conducted by the great editorial team including Paulina Reiter, Gunia Nowik, Patrick Komorowski and Alex Benenson. We are going to bring these issue to Venice for the last week of the Biennale, end of November, to be available in the Pavilion.

A.U.: The theme of the 57th Biennale it’s been to place the artist back in the center: “I want to redesign a hierarchy in which art and artists come first”, said Christine Macel at Artnet. Do you think it succeeded in it? And do you think the Polish Pavilion has achieved this statement?

B.P.: I might disappoint you here. We constructed this project and applied with Sharon before Christine and Biennale announced the topic and the idea for the main exhibition. I think the center of the Little Review project was not an artist, but her collaborators: the Rudzienko girls.

Sharon Lockhart, Little Review, Polish Pavilion, 57. Venice Biennial, 2017, exhibition view, photo: Bartosz Górka

Alex Urso (b. 1987) is an artist from Italy, currently living in Warsaw.

Together with his practice as visual artist, Urso is as well engaged in curatorial projects and critical writing. In these years Urso has been collaborating with private and public art spaces, such as National Gallery of Art – Zachęta, and the Italian Institute of Culture of Warsaw. In 2017 he’s been co-curator of the Biennale de La Biche. From 2015, he writes about art for the Italian art magazine Artribune, as correspondent from Poland. From 2014 to 2017 he is been editor for the Italian art magazine Lobodilattice. His writing has been published by magazines such as Contemporary Lynx, Italian Factory and Inside Art, among others.