Bożena Czubak is a founder of the Warsaw-based Profile Foundation that deals with the presentation of the modern art of the 1960s and 1970s. Additionally, she curates the three-year Recordings project – a series of live recordings’ screenings featuring happenings, performances and conceptual activities. Today, we discuss the idea behind the art project, a need to preserve the intangible legacy of the avant-garde, as well as the foundation’s plans for the future.

Recordings 2018. New Artistic Practices of Artists from Yugoslavia, exhibition, Profile Foundation

Michalina Sablik: A series of meetings, events and exhibitions devoted to the neo avant-garde practices, performance and new media art of the 1960s and 1970s is orchestrated as part of Recordings. Could you please elaborate on the reasons behind the projects’ formula?

Bożena Czubak: My long-standing collaboration with Józef Robakowski was paramount to the Recordings’ programme. We’ve had multiple conversations about the films and video documentation of the live artistic practices. Obviously, Robakowski himself is an extraordinary artist who has always been actively engaged in preserving some kind of account of other artists’ activity. As time goes by, the value of those archives, those records of performances enacted over fifty years ago, has increased exponentially. The artists of the 1960s and 1970s relished in ephemerality, going out into the streets on both sides of the Iron Curtain to perform their pieces in the natural environment. Therefore, all we have left now is “the second hand” knowledge we gain from video recordings or documentary photographs, freeze frames which invoke a fragmentary message even though they are usually accompanied by explanatory descriptions.

Robakowski ushered in an incredible shift in the general approach towards documentation. Circa 1975, he started working on this film that was commissioned initially by the Museum Sztuki in Łódź, but then turned into his own independent project. Robakowski’s own role was reduced to that of a coordinator or director as he invited about twenty other artists to present their works in front of a camera. The duration of each performance or performative action couldn’t exceed 90 seconds. The participants included some of the most renowned avant-garde artists in Poland, such as Jerzy Bereś, Zbigniew Dłubak, Natalia LL, Andrzej Partum, Zbigniew Warpechowski and Ryszard Waśko. This documentary film titled Living Gallery (Żywa Galeria) became an actual living breathing gallery space.

The Italian section of Recordings, which we held several days ago, featured some fragments of Identifications – a film by Gerry Schum who launched his “Television Gallery” in the 1960s. The artist used to travel the globe in his car, which he converted into a dwelling and production studio, in order to register the pieces performed by major artists. In 1969, he captured some land art practices of for instance Richard Long, Robert Smithson and Walter de Maria. A year later, Identifications presented the profiles of the Italians, such as Mario Merz, Gino de Dominicis, Giovanni Anselmo and Alighiero Boetti, whose works were also exhibited as part of our festival. Recordings is always proud to host the premiere screenings of the previously unseen footage.

I’ve mentioned Robakowski due to the fact that it were our conversations that have bolstered up my belief in the significance of the film recording. The need to screen and share these materials is indisputable.

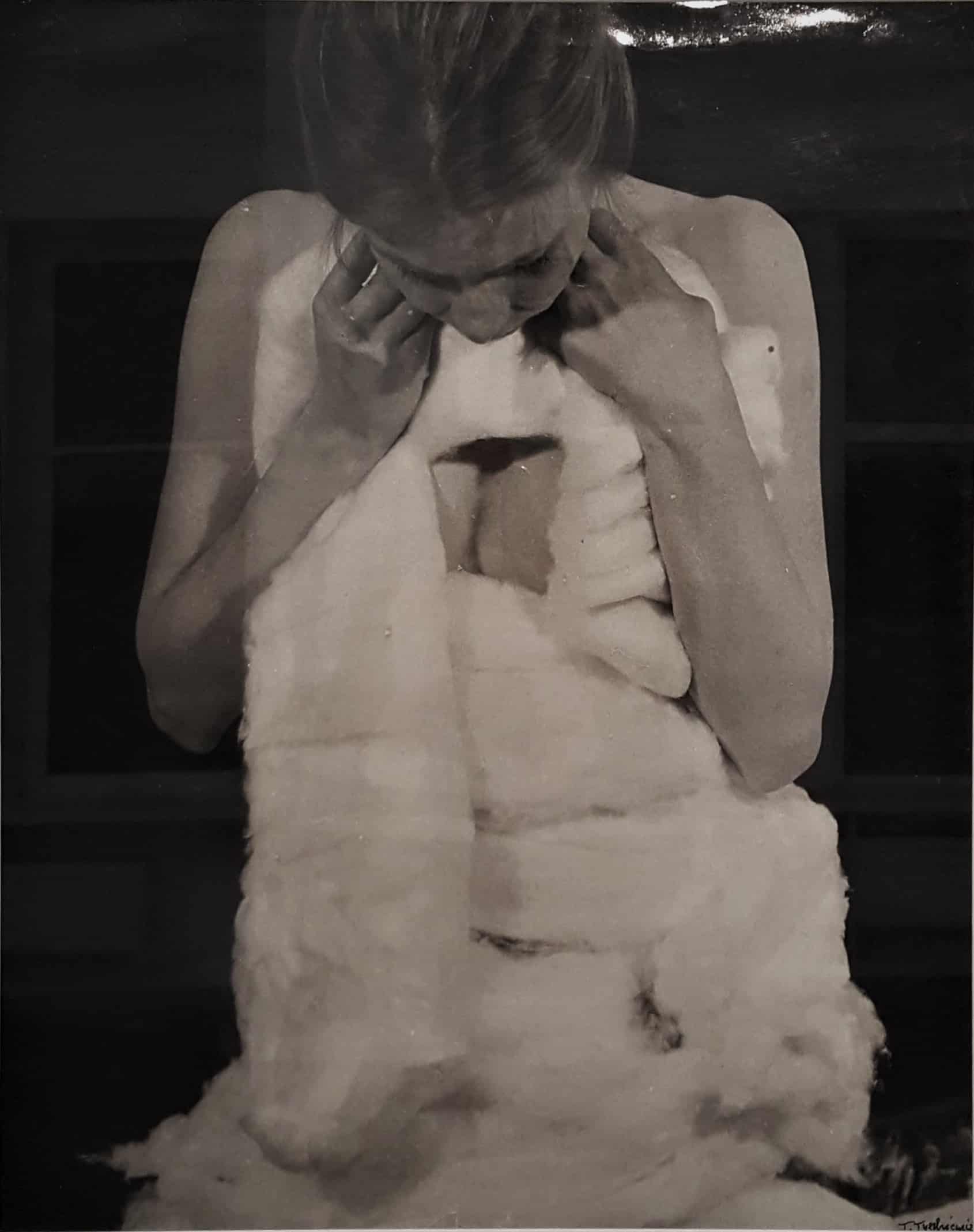

Teresa Tyszkiewicz, ‘Cotton Wool’, 1980, photography

MS: The status of film recording has transitioned from the piece in a contemporary art collection to the valuable object on the art market. I suppose there’s still no institution of culture that would express a serious intent to preserve the intangible legacy of the neo avant-garde in Poland. Is the Profile Foundation going to fill this gap?

BC: In my opinion, this gap extends far beyond the Polish boundaries despite a rekindled interest in this sort of documentation. Sure, there’s obviously Filmoteka (Film Archives) by the Museum of Modern Art in Warsaw, but its focus is directed rather towards the audiovisual works of art. The epitome of an institution of culture which successfully deals with artistic documentation is Galleria Civica d’Arte Moderna e Contemporanea in Turin, Italy. Its video archives have been amassed since 1999 by Elena Volpato who gave introductory remarks at the Italian avant-garde screenings. All in all, we were granted access not only to the Italian archives, but also the exceptional footage obtained by Marinko Sudac from Zagreb, whom we’ve collaborated with since last year’s edition of the Recordings. He was kind enough to lend us fairly unknown video documentation of the fantastic pieces performed by the artists from various regions of the former Yugoslavia. This year, we’ve also tapped into the resources of Electronic Arts Intermix in New York. Needless to say, some of the materials were supplied by courtesy of the artists.

Recordings 2018. New Artistic Practices of Artists from Yugoslavia, exhibition, Profile Foundation

MS: Your events give voice to the scholars and representatives of various institutions. Why don’t you reach out to the artists themselves? Many of them are still alive and well.

BC: Last year, the entire section of Recordings was devoted to the art practice of Ben Vautier, one of the key figures of the Fluxus movement (Les acstions de rue 1962-1985). We would’ve been honored if he decided to participate in the festival. Unfortunately, he couldn’t make it due to health reasons. The programmes tend to incorporate works of art by several or dozens different artists. Therefore, we would much rather give platform to the impartial experts who are capable of drawing a bigger picture, spelling out the contexts and origins of each work, answering questions the audience might have about all the films.

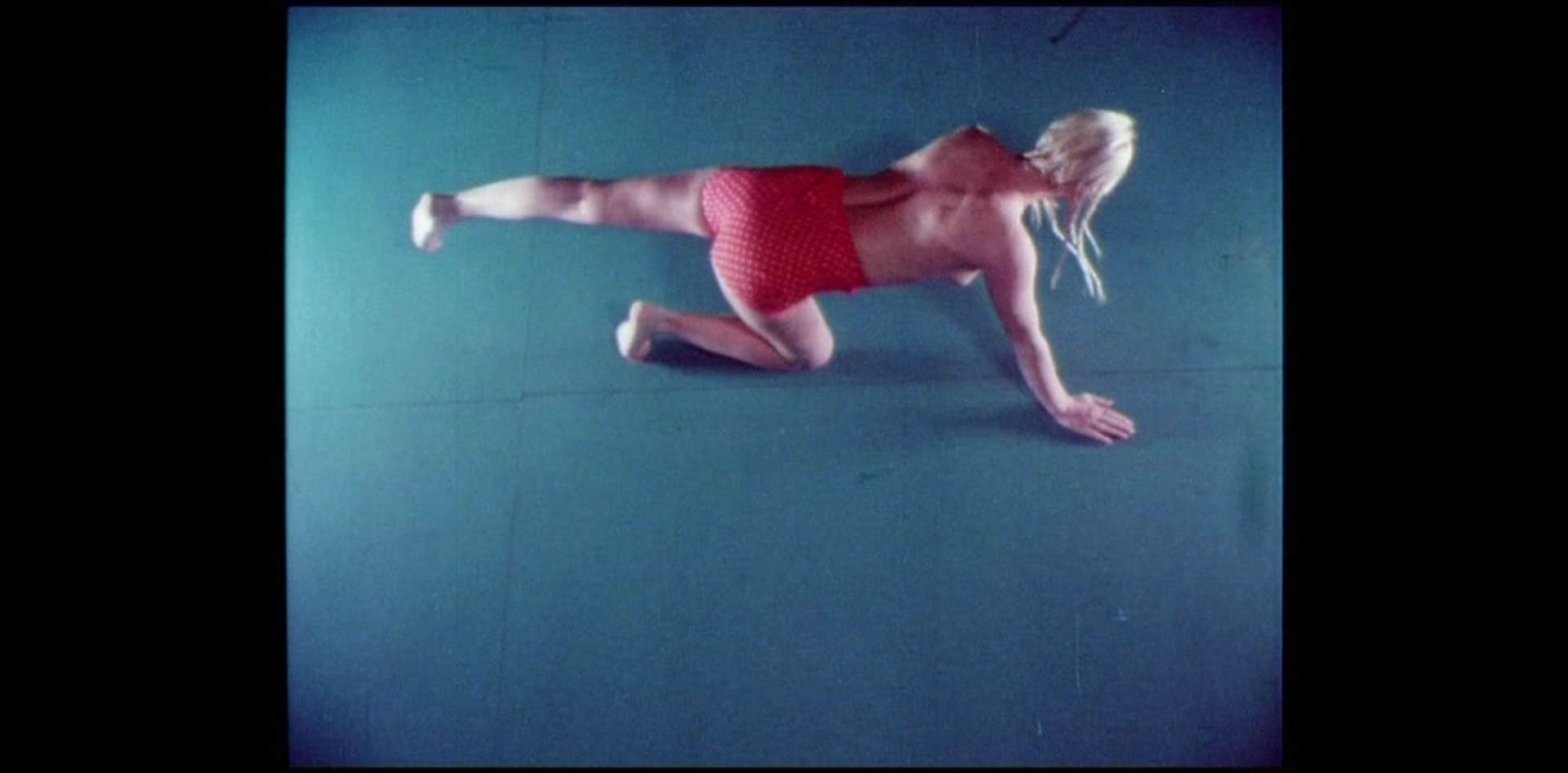

Natalia LL, ‘Points of Support’, 1980, courtesy of the Lokal_30,

MS: The art scenes in New York, Naples, Turin and Zagreb provide a backdrop for your presentation of the neo avant-garde art from Poland. The juxtaposition reveals some formal correspondences between the types of experiments undertaken almost simultaneously all around the world. Was there any bilateral exchange of ideas between the national and global art circles?

BC: Recordings runs for three years in total. Each year, the festivities culminate with the screenings of the films made exclusively by the Polish artists in order to highlight their contribution to the neo avant-garde movement as a whole. In the 1970s, the artists were quite enthusiastic about collaborative art projects, which is for instance illustrated by NET inaugurated by Jarosław Kozłowski. The project, which we tried to encapsulate in the form of a two-part exhibit and an accompanying book, brought together a group of over 400 artists from Poland and abroad, most notably Ben Vautier, Radomir Damnjanović Damnjan, Yoko Ono and Bogdanka Poznanović. Their works were also showcased during Recordings. Though largely epistolary in form, their relations did result in a series of exhibitions that were held in Kozłowski’s Akumulatory 2 Gallery in Poznań since 1972 despite (or in defiance of) the geopolitical restrictions imposed on the artistic production. Furthermore, Józef Robakowski, who was running the Wymiany Gallery in Łódź, managed to establish a collaboration with the artists from Zagreb and Belgrade. Besides according to Robakowski, the gallery might’ve never even existed if it weren’t for some Yugoslavian artists leaving their works behind around his place.

Vlado Martek, Sven Stilinović, ‘Admit that you are an artist’, 1985, Marinko Sudac Collection

MS: Due to voluminous research, a hermetic group of artists has been established firmly in the canon of the neo avant-garde. For several years now, we can witness a general public’s predilection for this particular period in the art history that has spawned multiple exhibits, books and catalogues. The real question is whether there’s anything left to say. Should your audience expect to make some new exciting discoveries as far as the fairly unknown names and artworks are concerned?

BC: I wouldn’t necessarily say that we would introduce the audience to some brand-new figures from the art world. Our intention is rather to accentuate some obscure aspects of the creative practice represented by those artists we’re already familiar with. Apparently, people’s insight into their vast oeuvre often boils down to some famously iconic pieces. There’s still a lot to be done in this regard. The Profile Foundation was established over a decade ago with a view of reframing the foundations of contemporary art which can be traced back to the 1960s and 1970s. We’ve overseen several large-scale projects and published some elaborate volumes on this very subject. The academic studies have also been thriving for a while now. However, distinct scientific approach and methodology would emerge every decade or so. This shift in perspective and main point of focus lays bare some new exciting aspects of the field.

Ewa Partum, ‘Change’, 1974/2016, photography, Courtesy of the artist.

MS: It’s also worth mentioning that your project showcases the feminist art of the women artists of the 1960s and 1970s. Does the festival shed light on the practice of Ewa Partum, Natalia LL and Teresa Tyszkiewicz? Is there a need for yet another reinterpretation of their works?

BC: The festival offers the audience a chance to view the source materials (i.e. film recordings of the actual works of art) that may encourage meditation on their meanings, not pre-packaged analysis. We’ll for instance stage the premiere screening of a short footage documenting The Change (Zmiana), Ewa Partum’s performance from 1974. I wouldn’t overestimate the amount of research into women artists of that period either. The studies published on the art practice of Ewa Partum or Natalia LL are a mere drop in the ocean. Nonetheless, the art of Teresa Tyszkiewicz, who has lived in Paris for over forty years now, has somehow slipped into oblivion. Fortunately, this glaring oversight is soon going to be remedied due to her upcoming retrospective exhibit in the Muzeum Sztuki in Łódź.

This year’s edition of Recordings starts with the New York art scene and ends with the feminist manifestos of the women artists from Poland. This juxtaposition exposes a conspicuous temporal shift – Yoko Ono, Carolee Schneemann and Joan Jonas made their feminist statements in the 1960s, while the Polish artists tackled the same issues in the late 1970s and early 1980s. To be fair, the access to the film equipment used to be fairly limited back then. This dire predicament improved in the 1970s owing to the Workshop of the Film Form and the artistic community in Łódź, which was formed around the local Film School. Both groups represented a major breakthrough in the accessibility of the highly advanced equipment, which was in short supply even in the West. However, this tight-knit crowd was rather the exception to the rule. A vast majority of happenings and performances was captured on photographs only.

Gino de Dominicis, ‘Tentativo di volo’, 1970, from Gerry Schum’s movie titled ‘Identifications’

MS: Could you give us a sneak peek into the upcoming edition of the festival?

BC: The next year’s programme revolves around the artists from the South America, Hélio Oiticica and Lygia Clark in particular. We hope to seize the recoding of Parangolés by Oiticica and screen the film in Warsaw. Additionally, an entire section of the programme will be devoted to Joseph Beuys – not only the iconic coyote piece, but also the records of his almost performative teaching in Dusseldorf, street happenings and politically-charged works. Another key figure of the German activism would be Wolf Vostell, who must also be recognized. The programme will also include the French section that would transport our spectators back to the 1950s, to Georges Mathieu’s theatre of painting, Yves Klein (obviously) and especially Jean-Jacques Lebel’s happenings from the 1960s, which the Polish audience is still largely unaware of. The 3rd edition of Recordings will culminate with the presentation of films featuring performances by the Polish artists of the 1970s.

Luigi Ontani, Saccombrello, 1969, GAM – Galleria Civica d’Arte Moderna e Contemporanea, Turin

MS: How will you celebrate the end of an entire project? Have you given any thought to the publication of a book, perhaps?

BC: Of course, publishing a book seems tempting. However, such an ambitious yet surely demanding initiative must be preceded by an in-depth research into the subject matter, not to mention the international team of experts, which we would need to assemble judging by the varied collection of works that were and will be presented as part of Recordings.