Something bizarre happened after pioneering sound installation artists in the 1970s declared that sound can be used in art as a sculptural material and an entity in itself: the art world (eventually) listened. But not to sound itself; all it heard was the concept that sound could be a sculptural material. And half a century later, perhaps it can be said that no form of art has endured such a meta, self-aware journey as sound installation art has.

Here’s the problem. Doesn’t a space in which sound is used as a quasi-sculptural material sound interesting? Of course it does. And many sound art writers think so, too. But an assumption is often projected onto sound installation because so many artists have created such intriguing ‘other’ spaces with their works. Think of pioneering American sound artist Max Neuhaus’s Times Square, widely recognised as the first major work of sound installation art. The installation is a mesmerising oasis in an island junction of New York City’s Times Square (amidst all its blaring car horns and bright flashing lights), created with a curious, soothing drone hum that resonates within a chamber beneath a metal subway grate.

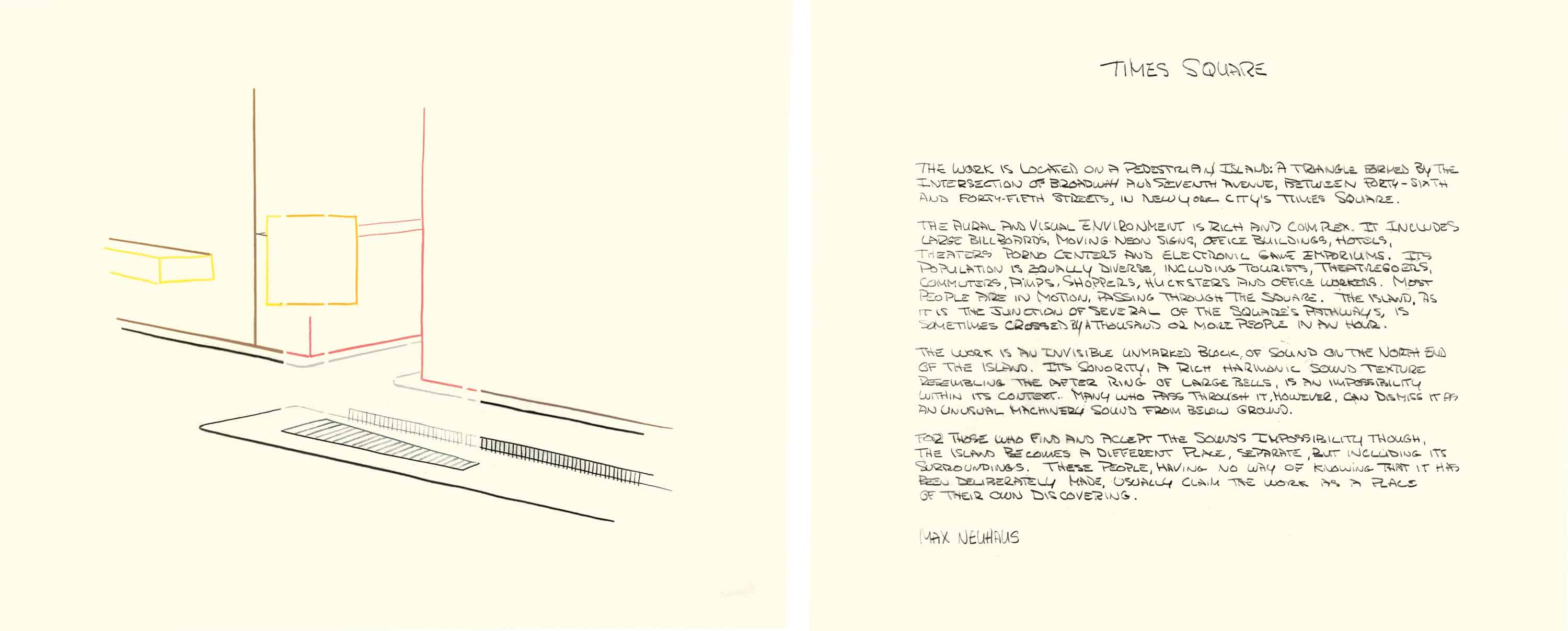

Max Neuhaus, Times Square 1992, © The Estate of Max Neuhaus, courtesy Dia Art Foundation

The assumption writers make is that sound installation takes you outside of space and outside of time. They borrow Foucault’s term “heterotopia”. Sound installations are heterotopias—mini-utopias within the dominant space (of capitalism), where social relations are non-hierarchical. Sound installations often evoke such a space, it is said—and Neuhaus even thought about his Times Square that way: “It doesn’t exist in time. I’ve taken sound out of time and made it into an entity.”

It’s poetic and beautiful, but wrong. Oxford University musicologist Gascia Ouzounian’s work on the sound installation art provides us a firm reminder that even the space within a sound installation is socially and politically constituted—all space is.* Truth is, you can make a space feel as if it is its own utopia, but it can never truly be outside the dominant order. To rearticulate a critique put forward by theorist David Harvey, Foucault’s idea of heterotopia is built on the false premise that some spaces exist outside the power of social order.** Indeed, sound installations may feel like mini-utopias, but that doesn’t mean they are actually outside social order. For example, through eminent domain (the US government’s power to seize any land) Neuhaus’s Times Square could be turned into a new subway entrance if required.

Why’s this important? The reason’s simple. What sound installation, as a form of art, is particularly effective at doing is creating affect. It creates and structures feeling within space. It relies on auditory perception, which bears huge weight on our cognition of reality. It incites more emotive response than seeing alone.

Much of the capabilities of the art form have been scoped out. You can play a recording of Renaissance music through 40 speakers in a circle, each with the sound of one person’s voice (Janet Cardiff has). You can map data from CERN into an immersive audiovisual experience (Ryoji Ikeda has). You can win the Turner Prize with a recording of your untrained voice playing through a megaphone by a river in Glasgow (Susan Philipsz has).

What you can’t do is meaningfully activate an audience by consoling them of the stresses of today’s world. Indeed, some sound installations are critical works and do more than console. But there aren’t enough. Try and find a sound installation in a local gallery—I challenge you.

This is a call for artists not to use sound as the building blocks of sonic sculptures but to create audiences that listen, audiences that tune-in to what’s really going on in this world. Sound is a sculptural entity—learn that, then forget about it. Because the kinds of sculptures it’s capable of building involve not just space but people, not just sound but an energy for action. And now really is the time.

*Gascia Ouzounian, ‘Sound installation art’, in Music, Sound and Space ed. Georgina Born (2013).

**David Harvey, Cosmopolitanism and the Geographies of Freedom (2009).

Written by Oliver Gudgeon

Oliver Gudgeon is a freelance writer based in London. In 2017 he completed a masters at the University of Cambridge, where he was awarded a distinction for his research and writing on the history and aesthetics of sound art. He now runs a blog called Contemporary Sound Art [https://medium.com/contemporary-sound-art] which aims to bring the small field to a wider audience. He is also a part-time staff writer at The Plus Paper [www.thepluspaper.com].

The note from the editors-in-chief: This article was published in Contemporary Lynx Magazine – in print, issue 1(11) 2019. We do apologise Oliver Gudgeon for making a mistake and published the wrong version of this article.