“It is possible to take fewer images. It is possible to take time. It is possible that the interaction of a photography shoot not be a robbery, a rape, or a self-portrait. It is possible to photograph something other than the spectacle of a fire.”

The Walls Don’t Speak, Florence Weber & Jean-Robert Dantou

Sinead Kennedy

Sinead Kennedy and Piotr Wójcik are two distinct figures – two different people of a different age, gender and origin, as well as two different artists. Interestingly enough, the thing they have in common sets them apart, namely their approach to documentary photography.

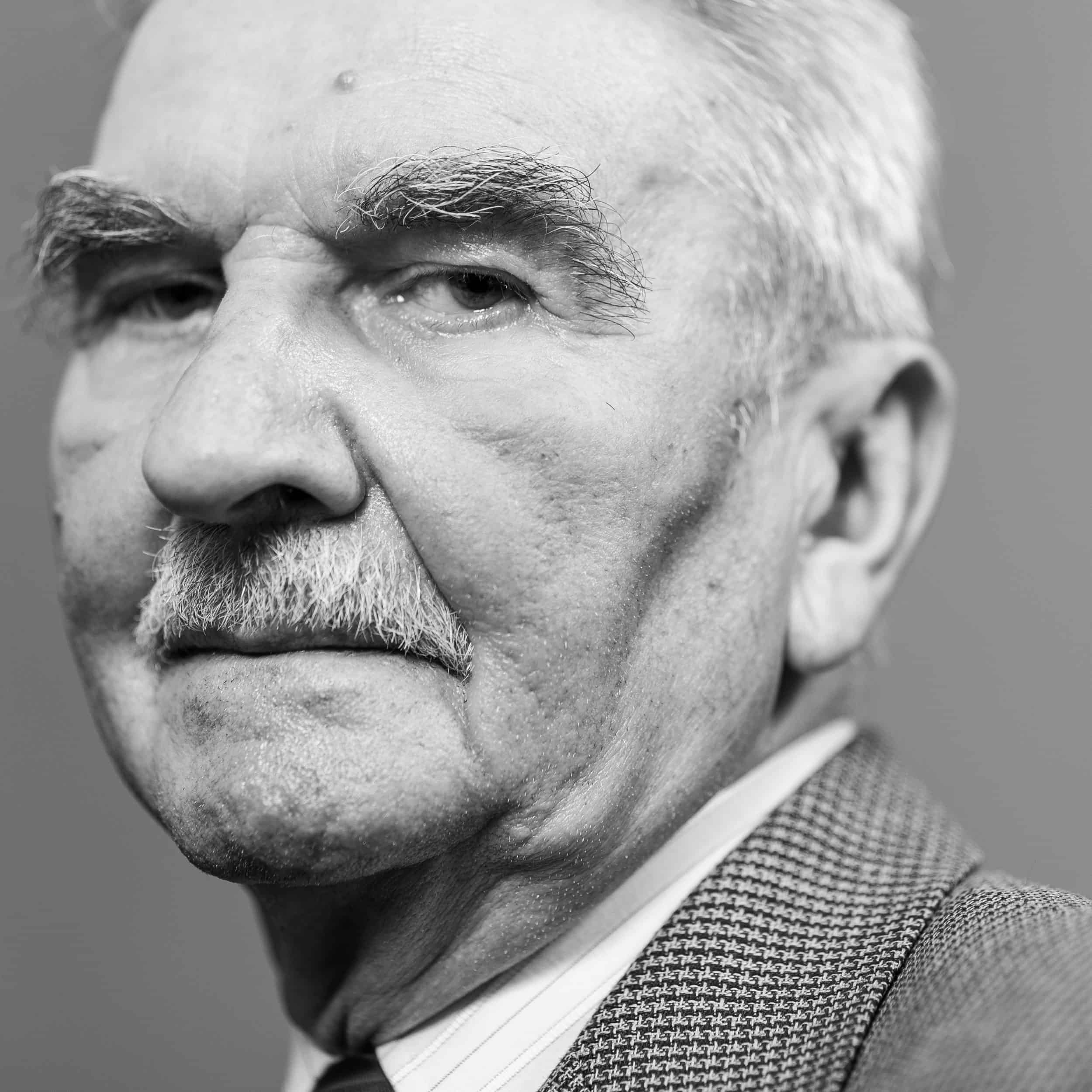

A broad spectrum of current changes in documentary photography is illustrated perfectly with the juxtaposition of the practice of Piotr Wójcik – an experienced photographer well-versed in the Polish tradition of photojournalism – and a young debuting female photographer from Australia. An esteemed teacher and documentary photographer, Wójcik belongs to the influential group of reporters that witnessed first-hand and captured the greatest socio-political transformations raging in the last decades across Poland and the world. The image tailored first and foremost to a publication in the press was then a form of visual storytelling accompanied by or tantamount to the written word. The image-text relation continues to manifest itself in Wójcik’s art practice in such projects as 30/100_PL.30 years of freedom, which was exhibited during this year’s Fotofestiwal in Łódź. These days, it’s hard to escape the impression that the form of narrative encompassing a visual representation of public information is undergoing a crisis. As opposed to the last twenty years, documentary photography is evidently expunged from its “natural habitat”, meaning the press. A paucity of editorials and photostories covering dozens of newspaper and magazine pages is rather undeniable.

photo: Piotr Wójcik

Technological progress combined with a downfall of traditional mediums has exerted the most profound impact on documentary photography. – Wójcik elaborates. – In the 1990s, the business of photography embraced young, technically agile photographers with high-end equipment – you could’ve gotten it anywhere, as intuitive digital cameras faster than analogue devices appeared on the market. This group was neither experienced nor educated in the process of image creation, but they offered a great bargain. The market was getting spoilt, the technology was getting more advanced. As a result, the advertising sector was highly professionalized, while the demand for photojournalism was falling. Through generally positive, democratization of photography brought about by a digital and hence simplistic medium played a crucial role in recent developments. Ultimately, newspapers stopped printing documentary features.

The crisis of “a conventional” approach to documentary photography might as well derive from the overproduction and decreased quality of visual storytelling. Another reason could be unrelenting determination – accompanied more often than not by a lack of satisfaction – expected from documentary photographers themselves. According to Wójcik:

Another aspect of the profession that should be taken into account is the fact that one’s Involvement in documentary photography takes a great deal of effort, that’s another thing I should mention. It’s extremely time and money-grabbing, often psychologically and physically draining. A lack of opportunities to share your work in print caused us all anxiety because it called into question the value of our own work. Everyone is familiar with the story of Krzysztof Miller, a distinguished Polish photographer who committed suicide for a number of reasons, but frustration or an absence of any sense of professional fulfillment must’ve been one of them. And when it comes to the power of visual storytelling, then I believe the audience is still captivated by the “inward” states that register a certain “process.” A look from a distance, “from the outside” rarely stirs things up to such a degree.

Sinead Kennedy

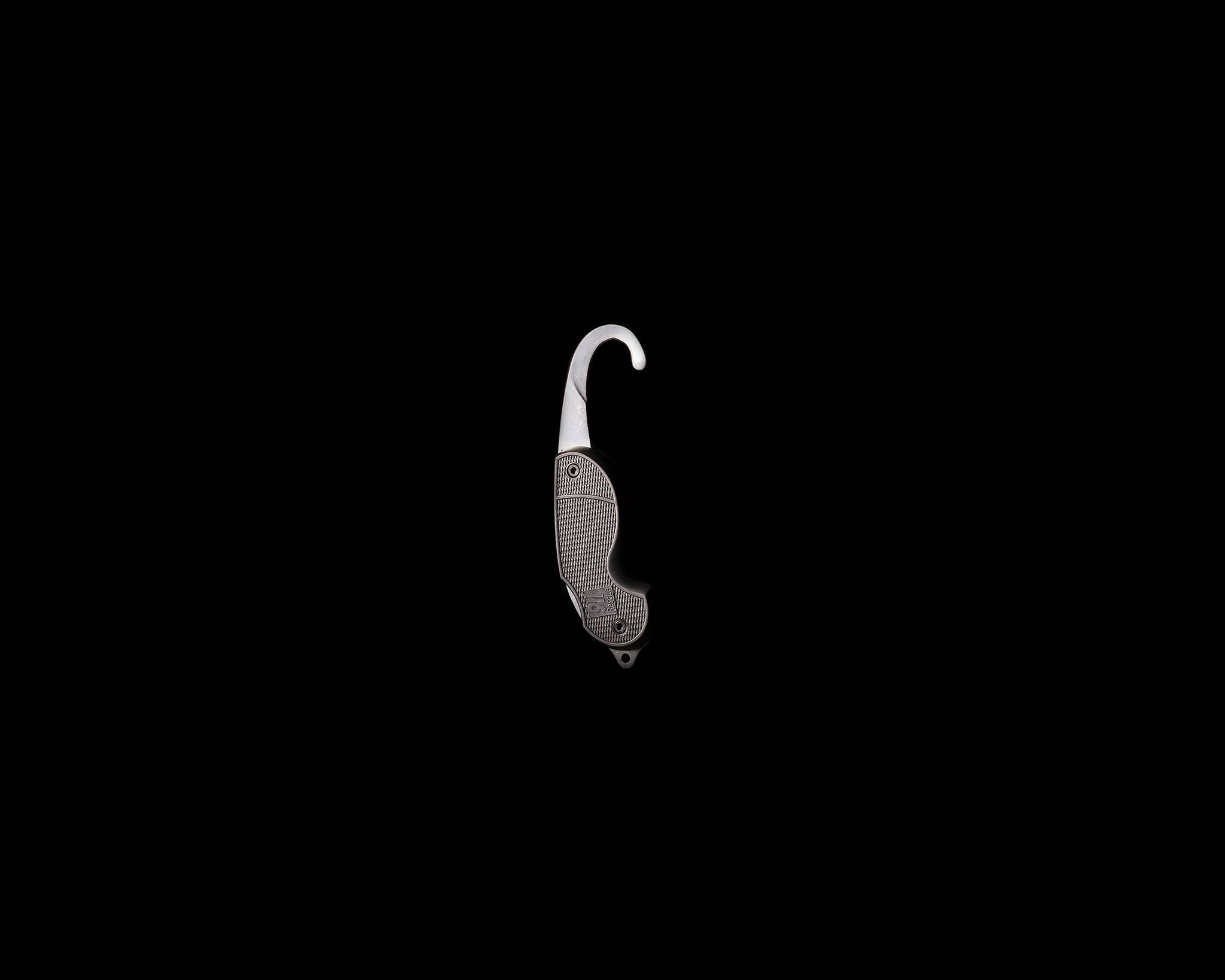

A need to immerse oneself in someone else’s “inner world” pointed out by Wójcik is reflected for instance by the art practice of Sinead Kennedy. Awarded the second prize in PHMuseum’s Women Photographers Grant, Set Fire to the Sea defies the convention of documentary photography. Even though a series of images “tells a story” underlined by pieces of writing, the narrative is anchored neither in time nor place. There are no characters. Kennedy’s storytelling rests upon a collection of unadorned compositions and sublime color schemes depicting some isolated mundane object or an accumulation thereof. Still, her series of photographs is a powerful and perspicuous representation of human experience: it is the story about immigrants awaiting permanent stay permits in the Australian detention centers, about their daily lives or rather daily existence.

There are a couple of phrases some mentors of mine use that open up the notion of documentary photography: “nonfiction visual storytelling” and “expanded documentary.” – Kennedy explains. – I see my work as sitting well with these terms, as work that tries to grow out from the direct ‘document’ into something more interpretative. It comes out of a different approach to research, process of image making and visual language, but I don’t think it’s any less real or true. The images aren’t elaborate or overly descriptive, maybe to clear away some of the noise that often surrounds this topic, and to allow space for the reader to enter on their own terms. The project is a collection of these small exchanges or fragments, distilled into a collaboration of text and visual to create a space that shares a story.

Beyond the shadow of a doubt, the means of visual storytelling in photography have been transformed completely within the last two decades, leaning toward affectiveness and elusiveness while abandoning a very straightforward and literal depiction. – Wójcik adds. Kennedy’s project seems to be a perfect embodiment of the above statement.

photo: Piotr Wójcik

Although Kennedy addresses a socio-political issue, she opts for a departure from a literal depiction of reality, from capturing the world as it is and as we all know it. As a result, the image itself becomes her subject. Not only does Kennedy build the narrative revolving around detention centers, she also raises the question pertaining to the medium itself – is photography capable of reflecting a human experience? Her focus on the medium is unprecedented. Typically, documentary photography abides by the paradigm of visual storytelling devoid of self-reflection.

The community itself has also been affected by the recent permutations in the field. Things have changed, absolutely. Two decades ago, an integrated scene of documentary photography was thriving fueled by a sheer force of rivalry for visual storytelling. – Wójcik comments. Indeed, the most exciting projects which could be labelled as “documentary” gravitate towards photography as an art form. In fact, Set Fire to the Sea was never published in any magazine. Nevertheless, the project is currently on display in the Robert Capa Contemporary Photography Center.

photo: Sinead Kennedy

Assuming documentary photography has already been embraced by the art world, one would have no other choice than to come to terms with an altered dynamics of its scene: a nuclear world existing simultaneously yet separately; myriad individual projects and photographs whose themes, resonance and visual language are all determined only a single entity – the creator. What is more, spectators themselves are gaining the autonomy. Nowadays, documentary photography is the domain of singular viewers in lieu of mass audiences that gaze upon the images in popular press. Documentary photographs are now featured in art galleries, independent publications and thematic festivals. In order to seek out these images, one must exhibit a certain level of expertise and resolve. The image no longer finds its audience, it is the audience that finds the image. If World Press Photo does in fact reflect the current state of documentary photography, then it would seem that the field is plagued by its portrayal of all the things familiar: depictions of anonymous suburbs in the war-torn Syria, hunger in Africa and other iconic symbols only confirm our pre-absorbed common knowledge. If we are to recognize the “new” point of view in documentary photography, the crucial distinction must be made between the images showing us “what we know” and the photographs of “what we get to know.”

What drew me into this subject originally was its lack of visibility and accessibility.- Kennedy confesses.- The unsettling feeling knowing there are whole lives being lived out in these centers, tucked away on neighboring islands and even my own city. It was important to me that the work spoke to this fact, the intentional hiding from view by systems of concealment. That is perhaps where the method of reconstruction came in. Where for lack of access or for being a dream, a memory or a past event, the story was not ‘visible’, and to create a visual was to create an entry point to this situation or experience.

photo: Piotr Wójcik

Even if documentary photography is fading gradually into the background of our daily lives, it does not necessarily entail a downgraded status of the medium itself as a significant vessel for history and reporting. The fascinating shift refers rather to the appropriation of documentary photograph by the artists. All this recent political, social and economic turmoil might have simply acquired an almost performative character and thus a more profound resonance. Perhaps all the stories, all the seminal global events have gotten under our skin, seeped unnoticed into our bloodstream while manifesting themselves in the life stories of ordinary anonymous persons in dire need of contact and intermediary. Here is the point where the debut of Sinead Kennedy and the still evolving practice of Piotr Wójcik meet. In consequence, the means of visual storytelling have been altered. Photography which captures the world has been relegated to the inaccessible peripheries, to the art world that expects you to scour for pieces of information instead of exposing them in print.

BIO:

Piotr Wójcik – photojournalist and author of photography books; a former photo-editor in chief of Gazeta Wyborcza and jury member of numerous photography competitions organized in Poland and abroad. He currently teaches at the Leon Schiller Film School in Łódź.

Sinead Kennedy (b.1993) is an artist based in Naarm Melbourne, Australia. Her practice is guided by an interest in photography and social issues; currently exploring the politics of migration and asylum in an Australian context. She explores expanded documentary as a mode of visual storytelling. Sinead studied a Bachelor of Photography at the Royal Melbourne Institute of Technology. Her work has been exhibited in photography festivals in China, Australia and Croatia. She was selected for Oculi Collective’s inaugural internship program and recipient of the Pool Grant in 2017. In 2018, she has had solo shows in Sydney and Melbourne, was selected to take part in Parallel Cycle 2, and awarded second prize in PHMuseum’s Women Photographers Grant.

Sinead Kennedy