RP: Could you tell me about the nature of your work?

AJ: I work mostly with performance, video and sculptural gestures. I think creating ephemeral work is more suited to our times than a solid monument. And it is also more challenging and exciting for viewers to experience.

RP: How did you start working as an artist?

AJ: I joined a photo society in secondary school and I thought that applying to an Art Academy would be a good idea. My parents were terrified. I did my BA in photography but soon I realised that it was not what I wanted to do. I applied to Media Arts studies in Warsaw, where I studied under Mirosław Bałka. I was very lucky to meet Mirosław and later to become his assistant.

Anna Jochymek, Melody of Nostalgia workshops, 2018, Sound performance (workshop part), collection of melodies recorded by Eastern European Migrant Women and male choir, Centrala Art Space, Birmingham, Photo: Anna Pudło

RP: Bałka is one of the most acclaimed Polish artists. What was it like to work with him?

AJ: It was a crazy adventure. He’s an amazing artist and person. But he’s also an eccentric guy, so it was full of ups and downs. We used to laugh that we are both Sagittarius so it is in our nature to be a bit edgy. He gave me one of the best advices I have ever received – that I should think big first and then worry how to achieve it.

RP: He’s got a lot of connections here in London. Do you think those connections brought you here?

AJ: I visited London first as a student and later as Bałka’s assistant. He arranged meetings with directors of major galleries. We met Gregor Muir at ICA and Iwona Blazwick at the Whitechapel among others. It gave us an insider view of the local art scene. Maybe that gave me the courage to think about moving to London, but London has always been closer to my heart than Berlin for example.

RP: It sounds like you see London as an important place to be as an artist.

AJ: It’s just a different city from the ones I have always known. When I decided to move here, I felt that I needed a change in my life. I used my PhD studies as an opportunity to move here. I asked the International Office at the Poznań Academy if they had any connections with London’s universities. They told me that they didn’t but I could arrange it myself, so I did.

RP: You find yourself here in London, doing this non-commercial work but London is a highly commercial place in terms of art. What were your first impressions of this art world?

AJ: Stupid me! [laughter] It’s not a secret that London is commercialised. You have galleries, auction houses and art fairs here. Besides, I believe that there is no better place to be as an artist who works with conceptual art in performative way. The environment that is not saturated by practices similar to mine can be good for me. London is a culture capital. The biggest world institutions work here with artists I admire. I can see it live, here and now. I can speak with people who create this atmosphere, learn from them and hopefully, in near future, work with them. Watching things on-line can’t replace the real experience.

Anna Jochymek, Melody of Nostalgia, 2018, Sound performance, collection of melodies recorded by Eastern European Migrant Women and male choir, Centrala Art Space, Birmingham, Photo: Anna Pudło

RP: So you’re finalising your PhD at Poznań Academy and your time here at Slade is some sort of a student exchange?

AJ: Yes, I was a visiting student-researcher here. Initially, I came here for three months but after two months the university said that I can stay for the whole academic year. After a year I was invited to join their new project “Sharing Borders” and offered the position of Honorary Research Associate. It was not only a huge credit of trust but extraordinary opportunity to develop as a professional in the structures of one of the most important British universities (UCL).

RP: Could you tell me about your PhD project?

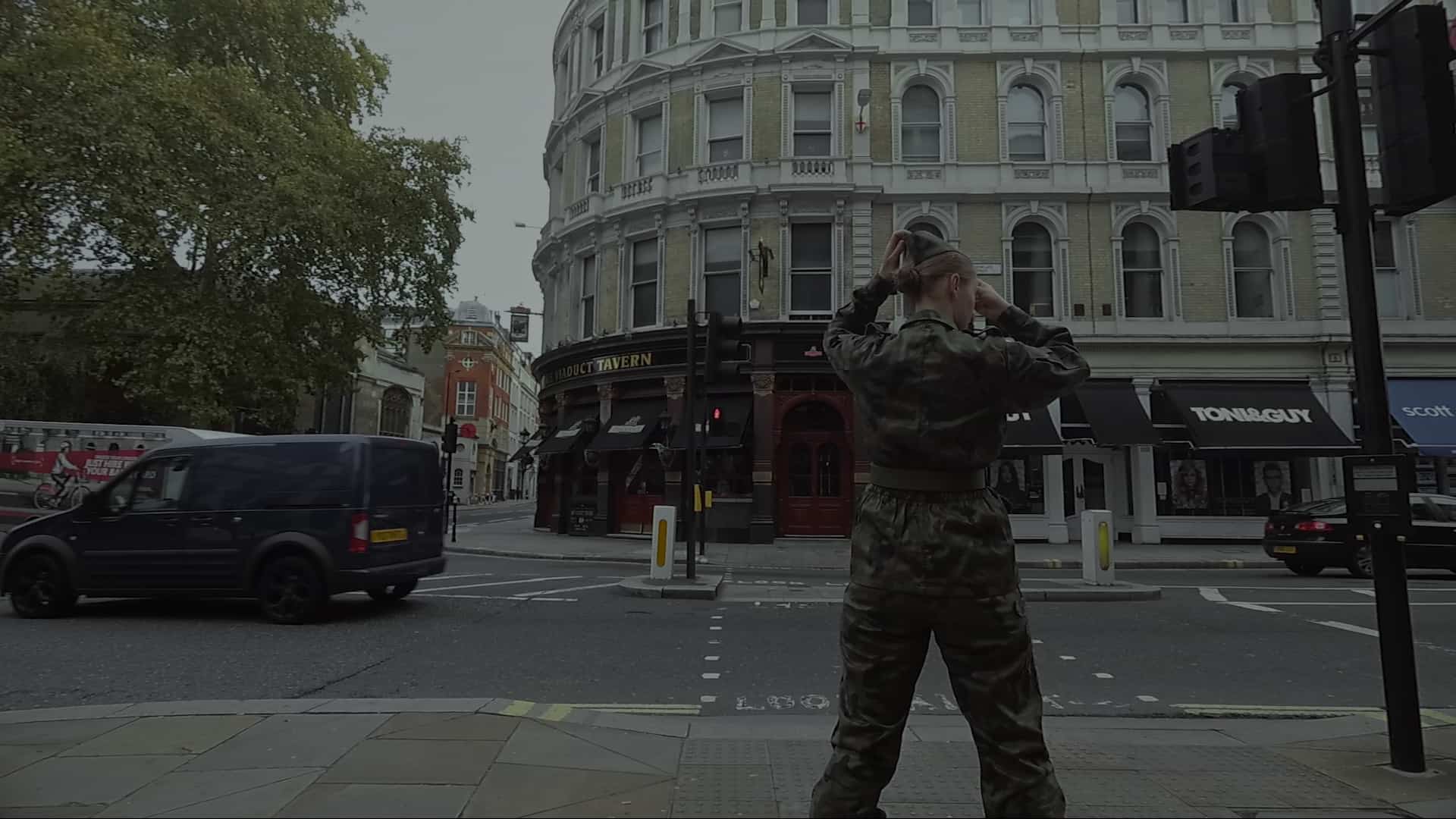

AJ: I was struggling a bit with my presence here, I was observing the political situation in Poland and the Brexit battle. My PhD project is related to space, fear, power and mass. I am fascinated by Elias Canetti book and it was really important for me to transfer that theoretical research to my practical work. I invented a figure of female Polish soldier skating in the streets of London, appearing and disappearing. Like a dream that never happened. It’s a kind of absurd figure, however quite intriguing. I’m very interested in the visual side, how it affects pedestrians. What they might think, how they might react. Of course, I will never know because I will not have an opportunity to ask them.

RP: Is it important for you to reach people that normally wouldn’t go to a gallery?

AJ: It would be amazing to involve people who are not art educated and maybe do not feel so comfortable with crossing this ‘sacred’ border of a gallery space, but I think about the gallery audience too. The second part of the project will be a video installation.

RP: What is the significance of a female skating soldier?

AJ: I’m a skater myself and a daughter of a soldier. My father works as an instructor in a military school. When I feel unsure about something or I have doubts I always call him and have this relaxing chat about military structures. There is something very fascinating about the discipline and the structure itself. Skating and military are so different, but they also have much in common. I merged these two things and created an absurd figure of a skating soldier. It is a very tempting figure, representing my state of being somewhere in between as a migrant.

RP: You have come to the UK quite recently. Does being a migrant woman from Eastern Europe somehow affect you? There must be a reason you make the work about it. How important is that migrant label?

AJ: I am a migrant, but I’m in a privileged position; I can always go back to Warsaw. I’m a millennial and we move constantly. The label of being a migrant was given to me, so I started thinking about it. We have a huge migrant crisis in Europe at the moment. Our times are terrifying. I don’t want to avoid it. I want to understand it.

RP: Being a migrant is related to the recent work Melody of Nostalgia you realised in Birmingham. Could you tell me a bit about that work?

AJ: Melody of Nostalgia was the first project I made here in the UK. I was invited to do a project by Centrala Space in the context of Supersonic Festival, which allowed me to push myself into the field of sound art. I was already doing some research into my family history, which became the inspiration for this project. During the Second World War, my grandmother’s house was occupied by Third Reich soldiers, who let my family stay in the house under the condition of moving to the cellar. It turned out that the soldiers were Austrians and they were constantly listening to this very nostalgic and patriotic song about the Austrian Lake Bodensee. Both sides felt nostalgia. My great grandmother missed the time when she was a regular owner of the house, and the soldiers missed their country. That twist was very inspiring to me. When I moved here to the UK, I found myself in the position of a migrant for the first time in my life. I merged the experience of my great grandmother and my own and decided to create a universal melody of nostalgia. I collected pieces sung by Eastern European migrant women around the world. I asked the women to sing the songs themselves and send the recordings to me. I created a small database and then worked with a composer who combined all those melodies to create a new piece. I also invited a male choir who performed this piece live. Their task was to add an extra layer to the story, as I wanted to add male narration. After many hours spent together, we found a way to create this balance, one cohesive voice. I transferred my personal history into a more contemporary one.

Anna Jochymek, Melody of Nostalgia workshops, 2018, Sound performance (workshop part), collection of melodies recorded by Eastern European Migrant Women and male choir, Centrala Art Space, Birmingham, Photo: Anna Pudło

RP: How did you find people you worked with?

AJ: First, I collected music pieces. I worked with people invited through a Facebook campaign. I used social media to contact Eastern European women migrants from all around the world. I also had to find members of the male choir. Finally, I created a seven-person male choir.

RP: What songs were the migrants nostalgic about?

AJ: I was surprised by the material I received: some Polish songs, some in English and some without any words. I could recognise some songs from the 90s. In general, the pieces were very delicate and full of emotions. I didn’t expect the emotional impact to be so big. I was surprised that many songs had a folk vibe to them.

RP: Why did you want to juxtapose those songs with performing men? Why did you want those two worlds to meet? The world of women migrants and the male choir?

AJ: I’m a woman and I’m interested in creating democratic positions in the art field. So when I was working with women migrants – I was giving them voice and space to be vulnerable and emotional. I thought it would be nice to invite men to join women so that they could feel vulnerable and emotional too. It would be easy for me to create a piece that was fully performed by women – it would have a strong feministic drive. But I didn’t want to exclude half of the society from the dialogue about the female voice.

RP: Was it important that those men were not Eastern European? Or were they?

AJ: I was considering working with only Eastern European migrants, but in the end, I decided the project need a universal representation of men. It didn’t matter if they were Eastern European or British, I just needed men who were brave enough to embrace the situation.

RP: At the moment we are at Slade, where you still have your studio. Could you tell me about this space?

AJ: Being at Slade was one of the most exciting things that happened to me, mostly because of people I’ve met there. The cool thing about being a PhD student here is that you have a studio space, which is shareable with other students. I’m only allowed to stay here until the end of this month though. I will have to find a new studio space outside of these nice and warm academic structures.

RP: You make performance, so in a way, I would think you don’t need a studio…

AJ: There is something very important about having your own space where you can gather your thoughts. Studio space is a place where you can feel free as an artist. People experiment with materials; I’m experimenting with my thoughts and ideas.

Anna Jochymek, Crowd Crystal in progress, 2018 – 19, Performance and video, © Anna Jochymek

Anna Jochymek, Crowd Crystal in progress, 2018 – 19, Performance and video, © Anna Jochymek

RP: How would you describe your life in London?

AJ: I’ve never felt as busy as I am now. I understand what people mean by saying they have absolutely no time. Life in London is very expensive. At the beginning I had a small scholarship which allowed me to have this comfortable situation of studying, being in the studio, doing research and working on my projects. But soon I had to find a job to be able to pay my rent. On Fridays, Saturdays and Sundays I work 10 hours a day in a vintage shop in Notting Hill. The rest of the week, I spend in my studio trying to work on my projects. So it’s a difficult time for me because I only have four days to make research, read, watch, visit galleries, meet with other people and create projects. I hope it will pay off. My day starts at 7 am and ends at midnight. I find cycling a very important part of my daily routine. It is this amazing thing: I spend two hours a day experiencing the city. The most creative ideas appear in my head when I’m cycling.

RP: How can you describe your place in the London art world?

AJ: In Poland, it’s easy to be an artist who’s floating between institutions and private galleries. The art world is small and everyone knows each other. Here it’s much different. You have private galleries, artists that work strictly in the commercial sector and others who work with ephemeral, time-based art in more institutional context. The latter is where I see myself but I’m still trying to comprehend challenging and confusing British art and cultural context, as it is nonetheless a foreign concept for me. I’m in the process of exchange; I’m influenced by it but I also share my own perspective. I had a pleasure to meet many respected and globally recognised artists who inspired me and encouraged to aim higher and be proud of where I’m from. That’s what makes my work unique, and that’s also what is very much appreciated here. So far, my work has received a very positive response and I’m looking forward to what future brings to me in this city.

London, August 2018 / Update, August 2019