Piotr Lisowski

Michalina Sablik: I am glad we got to meet and that despite the pandemic and the lockdown, Wrocław could celebrate the 50th anniversary of Wrocław ‘70 Symposium. The whole city joined in celebration. There was a grassroots movement of many galleries and initiatives to commemorate this round anniversary. What kind of efforts were these?

Piotr Lisowski: The initiative started completely from the bottom up. At one point it turned out that a lot of people in Wrocław were interested in the symposium. An informal working group assembled, consisting of people who represent different cultural institutions and independent initiatives. Together we worked until mid-2019 trying to come up with a shared idea for the symposium’s 50th anniversary celebrations. Consequently, we came up with the concept which we called Symposium 70/20. It was supposed to start at the beginning of March 2020. Because of the lockdown we had to slightly move it in time and adapt some of the events to the new conditions that the pandemic brought. Currently, the situation is slowly stabilizing. A number of art, education, exhibition, and research related activities are being carried out. All of them are related—in one respect or another—to the historic symposium, looking at it from today’s perspective.

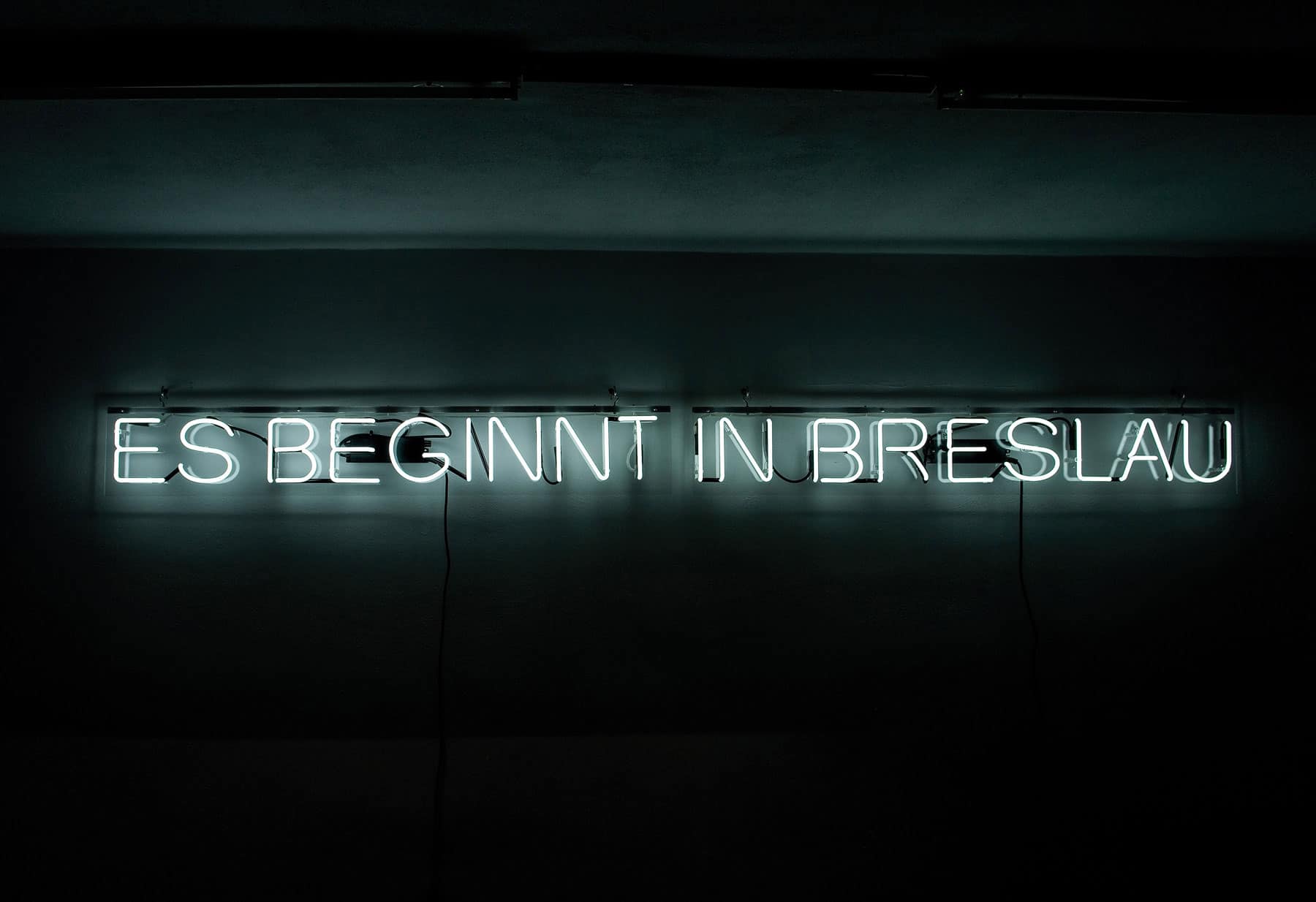

MS: Why was the symposium such an important event, the impact of which can still be felt today? Was its significance only local or a national one? I’ll ask by paraphrasing a sentence from Zbigniew Gostomski’s work: what begins in Wrocław?

PL: Wrocław ‘70 Symposium was part of the outdoor-symposium events initiated at the beginning of the 60s. This movement held a key significance for the creation of Polish neo-avant-garde community’s thought. The meeting in Wrocław in a way summed up the previous events that took place in Osieki, Zielona Góra, Elbląg, or Puławy. Zbigniew Makarewicz called it “the last avant-garde convention”. So, you could argue with Gostomski’s “It began in Wrocław” statement. The experiences of the past plein-airs were crucial here. In my opinion, the 1966 symposium in Puławy organized by Jerzy Ludwiński was especially important for the Wrocław ‘70 Symposium. Right after the end of the symposium in Puławy, Ludwiński came to Wrocław with a ready concept for the Museum of Current Art as well as the idea to organize a big artistic symposium, involving the Lower Silesian industrial works.

Zdzisław Jurkiewicz, Field of Perception, 1970, design, documentation from an exhibition at the Museum of Architecture in Wrocław. Photograph by Tadeusz Rolke. MWW collection

Anna Szpakowska-Kujawska, Spatial Composition, 1970, design, documentation from an exhibition at the Museum of Architecture in Wrocław. Photograph by Tadeusz Rolke. MWW collection

MS: There are many myths about the symposium, it is considered as the beginning of conceptual and impossible art in Poland. How did it come about? What works got presented? And do you deal with those myths at all?

PL: The legend around the symposium grew very fast. Already in the 70s the critics regarded it as the first, symbolic manifestation of conceptual art in Poland. The myth came from a paradox of sorts. The main concept of the symposium organizers was to introduce exceptional works of art into the city’s urban fabric. It was assumed that the created sculptures and spatial forms would build up a new spatial and urban structure of Wrocław; in the end however, none of the material objects came to life. Most of the submitted projects were meant to be implemented. Only a small portion of artists proposed projects within the area of impossible art. But these turned out to be significant enough to dominate the whole discussion. This myth has been long verified by the researchers. For example, Piotr Piotrowski wrote, slightly ironically, that the symposium became a manifestation of conceptual art because of the city officials’ inertia.

MS: Most of the symposium works were never carried out, they were mostly projects and conceptions that were presented in the Museum of Architecture. How do you present these works? Wasn’t there a temptation to recreate an unrealized urban project?

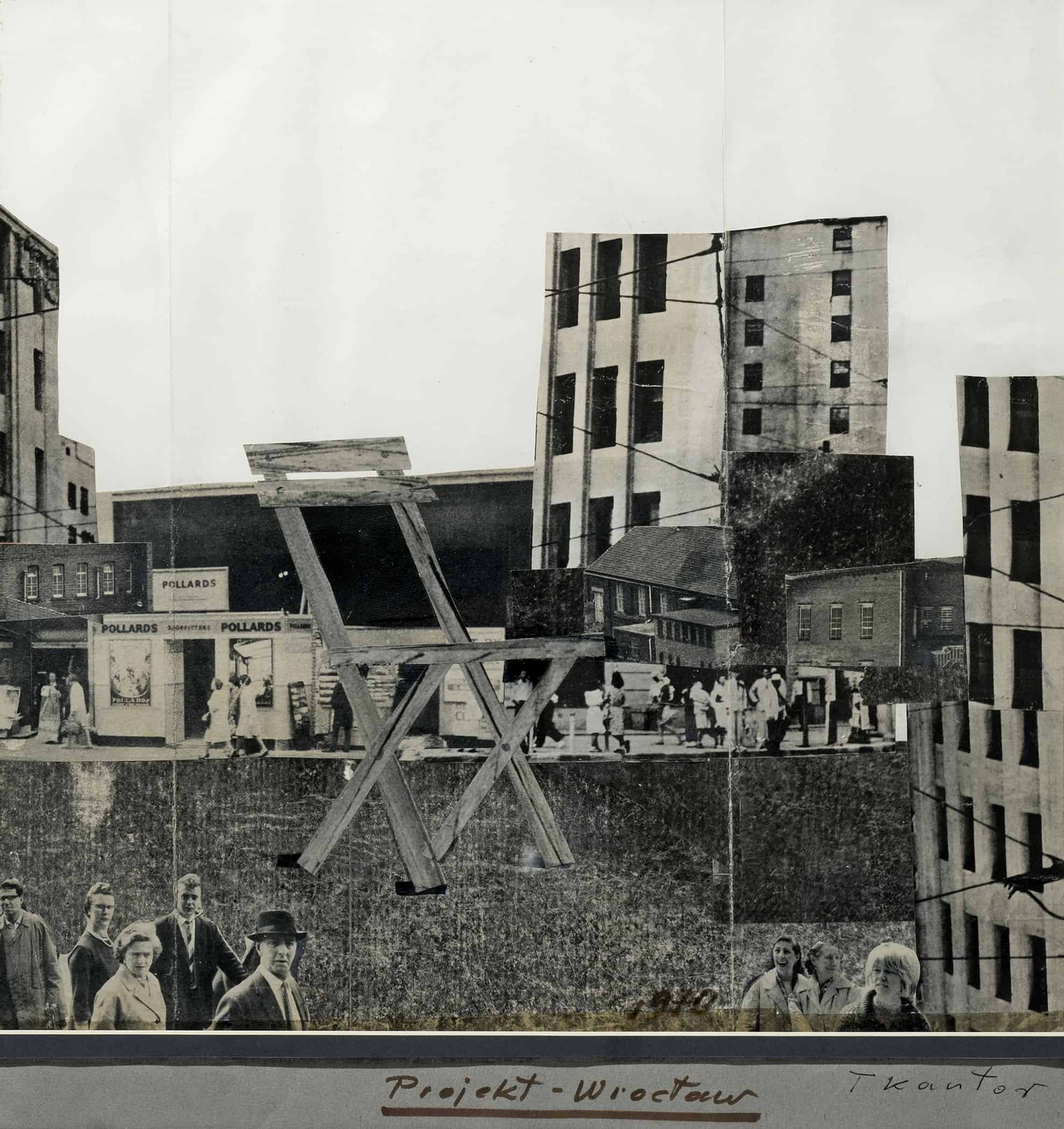

PL: During the symposium only one project got executed as scheduled. It was a work by Henryk Stażewski, “Unrestricted vertical composition — 9 rays of light in the sky” (“Kompozycja pionowa nieograniczona — 9 promieni światła na niebie”). By definition, it was supposed to be an ephemeral event. In 1972, Live monument “ARENA” (“Żywy pomnik pt. ARENA”) by Jerzy Bereś was built; it was then removed in the 80s, only to come back to that same place in 2010. A year later, “Chair” (“Krzesło”) by Tadeusz Kantor was created, and in 2016, a work from the symposium by Barbara Kozłowska was carried out — an interpretation of Stanisław Dróżdż poetry. These are the only physical works that were created within the city’s limits. It is worth noting, however, that they were all carried out ex post. The symposium was a multi-stage happening. Its culmination point was supposed to take place on May 9, 1970, the date of Victory Day, commemorating the end of World War II, and a time of central celebrations connected to the 25th anniversary of Recovered Territories. The symposium was officially written into the anniversary program. During the first rounds of discussions however the date was deemed unrealistic, which is why May 9 did not serve as a final date, but rather, as a starting date for the carrying out of the projects. No deadline for the completion of the works was specified. And so, following this line of thinking, it is tempting to say that the symposium never officially ended.

Tadeusz Kantor, Location of the Chair, 1970, collage, paper, 48 x 51 cm. Photograph by Mirosław Łanowiecki. Collection of the Museum of Architecture in Wrocław

MS: What’s left of the symposium then? What will you be presenting at the Wrocław Contemporary Museum’ (MWW) exhibition?

PL: Most of the materials got dispersed right after the symposium. Today they are mainly limited to photographic documentation, sketches and descriptions of ideas, and a few original project boards that have been preserved. The first attempt to put it all together was a monograph, published thanks to the Zbigniew Makarewicz’s efforts, over ten years after the symposium. MWW finds its identity in neo-avant-garde art. Since the beginning, we’ve been doing archival and research work on the phenomenon of the symposium. Most of the preserved materials are in our collection, supplemented by the collection from the Lower Silesian Society for the Encouragement of Fine Arts. We showcase a chunk of these materials at MWW, at the Jerzy Ludwiński Archive, a permanent exhibition/research space dedicated to Ludwiński, who without a doubt can be called the spiritus movens of the symposium.

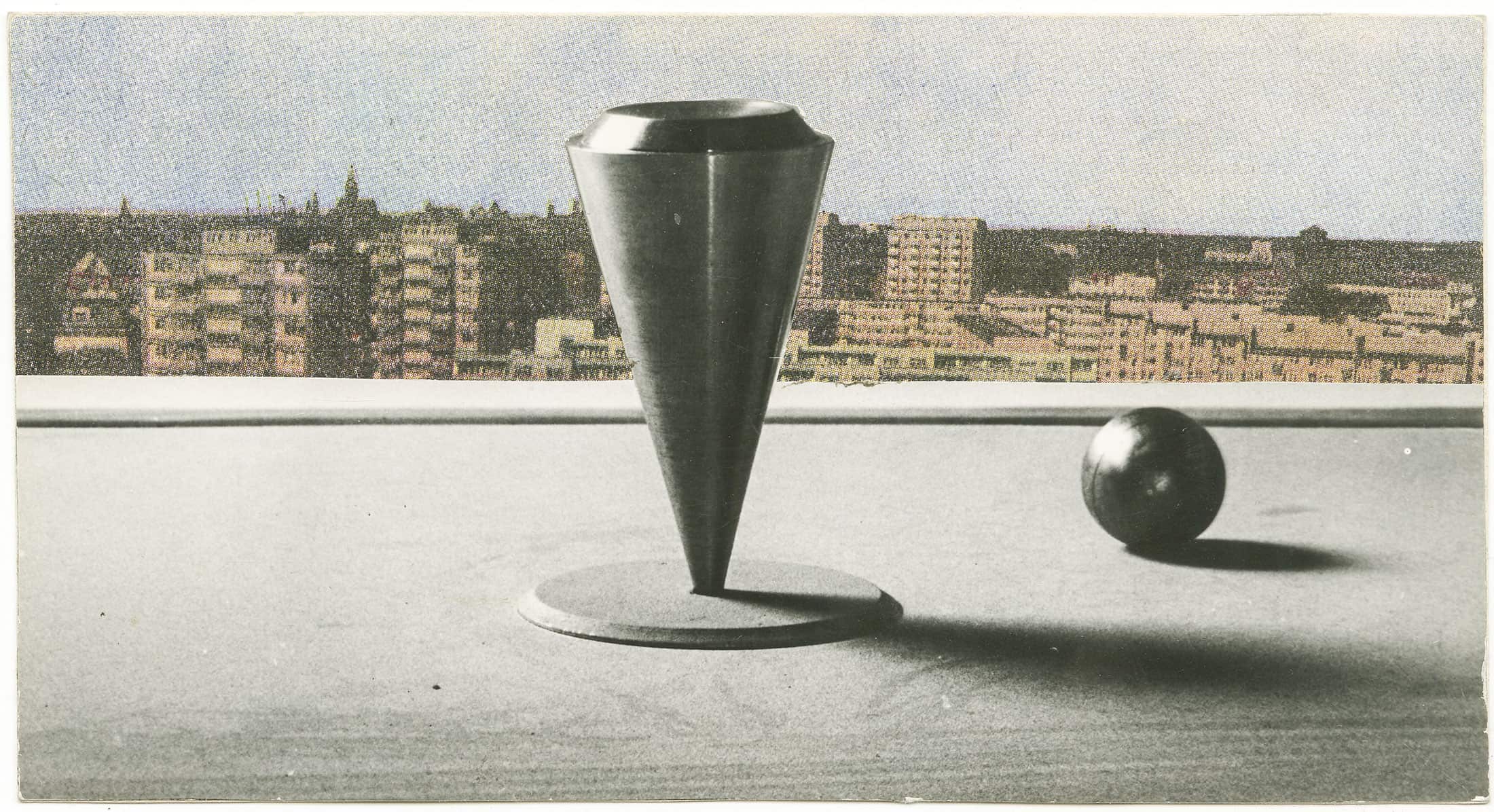

Henryk Stażewski, Unlimited Vertical Composition – Nine Streams of Colour in the Sky, 1970, documentation of the action. Photograph by Michał Diament. MWW collection

MS: An important part of the symposium were the discussions that artists and art theorists engaged in. Do those ponderings hold value and the same relevance today?

PL: The symposium was a grand discussion, a platform for thought exchange — not only in the area of visual arts but also urban planning, architecture, and public space. In principle, the symposium’s goal wasn’t to “decorate” space with sculptures, but for the artists to influence the city’s fabric, also through analysing it from an urbanistic perspective. Whole of Wrocław became a field of action. The most important artists and art theorists came to the symposium. Quite extensive transcripts of the discussions, which were immensely lively and fascinating, have been preserved. Indeed, this was characteristic of the whole of the plein-air and symposium movement. Ludwiński summed it up well by calling it “a moving art centre”, where the key concepts were discussed, argued and developed. I think the records of those discussions hold more value than just a historical one,which shows the specificity and the dynamics of that time. Many of the issues raised then still seem to be relevant. For example, the efforts to define the individual as he relates to public space, matters related to the awakening of visual awareness in the viewer, or questions about urban and spatial planning.

MS: The exhibition “New normativity. Wrocław ‘70 Symposium” won’t merely have the historical layer. How do young artists dialogue with the symposium?

PL: At the exhibition we analyse the symposium on several levels. You could say that we have carried out a curatorial and research intervention in the history of the symposium. The contemporary context is equally crucial here. This is why besides the purely historical narrative, the exhibition also deals with the polemical aspects of the events of 1970. Contemporary artists who got invited or the new works that were created, on the one hand, refer to specific questions and projects of the symposium or, on the other hand, engage in the polemic of neo-avant-garde art in general. We touch on issues that were relevant in the 70s and that are relevant today, such as: space, city, the role of the viewer. However, we limit ourselves to activities in the space within the museum.

Jerzy Rosołowicz, Neutrdrome, 1970, model. Photograph by Jerzy Holuka. Ossoliński National Institute. Ossolineum Library.

MS: Jerzy Ludwiński, who was referenced here before, during the symposium postulated the establishment of the Artistic Research Centre. For the exhibition at MWW you set up a space that is both performative and discursive.

PL: The Artistic Research Centre was meant to be a place of discussion, confrontation, research, and a place that would propel art. It was meant to be a lively place. Keeping that idea in mind I would like for the exhibition itself, in terms of its form and structure, to have a dialogical character. Furthermore, we have a number of accompanying events planned which we’d like to take place, as much as it will be possible, within the exhibition’s space. Those will be lectures and discussion panels but also educational and outreach activities. We also plan to include a few audio interventions. The whole exhibition will be somewhat summed up in a monograph on the symposium, which will be published by the end of the year.

MS: What does the titular New Normativity mean and where does it come from?

PL: The title is linked to the discussion on the symposium, which we talked about in the beginning. Was it in fact the first manifestation of conceptual art? Did it change and influence the way in which art is being thought about? I am interested in the dispute between the event being called the last avant-garde convention or maybe the first neo-avant-garde gathering. In this context, Ludwiński’s “Art in post-artistic era” (“Sztuka w epoce postartystycznej”) is important. It is worth considering whether the symposium was in fact the moment when — as the critic wished — post-artistic era began, and whether this idiom, developed at the turn of the 60s and 70s, can define contemporary phenomena.

Rafał Jakubowicz, Es Beginnt in Breslau, 2008, neon, 20 x 260 x 9 cm, ed. 1/1 + AP. DTZSP collection

MS: What activities are post-art for you today? And which works represent this attitude at the exhibition?

PL: Ludwiński once described conceptual art as art free from convention, where anything you think of can happen. Post-art is similar. Sticking to Ludwiński’s language you can say that post-art is “any” art. This art pouring over reality began during the symposium. The exhibition isn’t about post-art, but about the moment when it began to snowball.

MS: Recently, Sebastian Cichocki gave an interview for Magazyn Szum, Post-art in the state of emergency (Postsztuka w stanie wyjątkowym). In it, he talks about the twilight of a certain formation, about the end of “conceptual edifices” concerning the functioning of art that were created as early as in the XIX century. Throughout the XX century we saw this disarming and what Ludwiński observed and then tried to name and predict. What kind of role do you see for art and art institutions in the uncertain times that are coming?

PL: Institutions are becoming more and more flexible in their form; they are open to everything that is happening around them; this openness is immensely valuable. In my opinion, an institution should be at the same time a place of experimentation and of support. It is in that, that we should seek the utility of an institution: as a tool allowing for the processes of normalising a crisis, not only in the field of art. Nothing happens in a vacuum, so it is important to be sensitive to social relations and the surrounding reality. Art is not only the production of objects and meanings, it is also, and perhaps first and foremost, a physical presence, a by-product of relationships which are always soaked in the context of everyday life. In my opinion, emphasising these aspects is crucial for the institution which defines itself as a tool for communication and interpersonal interaction. Institutions should enable artists to create by providing them with certain tools and infrastructure; but they should also be a place of debate and a space that gives an impetus for action.

Anastazy Wiśniewski, Pillory, 1970, design, documentation from an exhibition at the Museum of Architecture in Wrocław. Photograph by Tadeusz Rolke. © Agencja Gazeta

Goran Škofić, Sector, 2014, HD video, 5 min 32 s. MWW collection

Władysław Hasior, Monument to the Victory of the Polish Soldier, 1970, project, plastic, glass, metal, ht. 94,5 cm. Photograph by Mirosław Łanowiecki. Collection of the Museum of Architecture in Wrocław

MS: Since the beginning of the year, you have been working in two positions — being the curator and the acting Director of MWW. How does the exhibition “New Normativity” fit into the programme of the institution you recently took over? Wroclavian conceptualism has been important for the museum from its beginning. What place will the legacy of neo-avant-garde hold in the MWW’s programme now?

PL: A natural gesture for the museum is to refer to Jerzy Ludwiński and the traditions of the 60s and 70s. Ludwiński’s thought is one of the pillars of our activity. There are still numerous topics to be recalled, researched or discovered. For example, Barbara Kozłowska, whose exhibition was opened not that long ago, yet who was one of the most original Wroclavian artists or Polish artists in general. I would like the main activities of the museum to follow two lines. On the one hand, they should be an expression of research and critical dialogue with the heritage of neo-avant-garde thought. An example that follows this line is our long-term project entitled Private Mythologies, focused on the contemporary interpretation of neo-avant-garde practices and their redefinition in the context of current art. On the other hand, I want the institution to be a place for activities and projects that face current problems and everything that surrounds us now. The New Normativity exhibition fits that first line, although it certainly goes beyond a purely historical presentation.

Zdzisław Jurkiewicz, Field of Perception, 1970, design sketch, drawing, pencil, paper, 30 x 41 cm. Courtesy of Alina Jurkiewicz